Полная версия

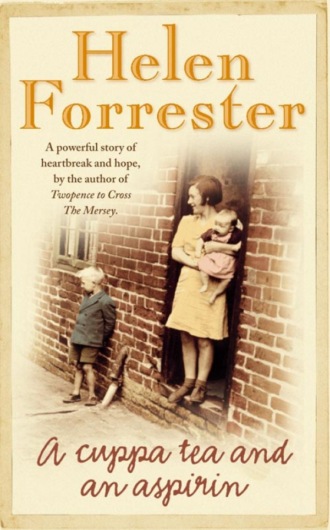

A Cuppa Tea and an Aspirin

Patrick swore to Martha, afterwards, that he did not plunge in to save him because he was a councillor and therefore important.

‘Might’ve left the silly bugger to fend for hisself, if I’d remembered,’ he told Martha scornfully. ‘What use is he to folk like us? And him a Prottie, too.’

But Protestant or not, he did instinctively plunge in to rescue the drowning man. A few powerful strokes and he caught him by the collar of his jacket. He shouted to him to stop struggling, but it took a second or two for the instruction to penetrate. Then, to Patrick’s relief, the councillor obeyed.

Swimming on his back, Patrick began to tow him towards the landing stage.

The current was against them and it took all Patrick’s strength to make headway towards the stage, where, as the accident was noticed, there was sudden activity.

With one hand Patrick finally managed to grab a hold on the gunwale of the little yacht.

As a crowd of helpers rushed to the edge of the stage, all shouting advice at once, the yacht threatened to turn over. One would-be rescuer with more sense threw a life buoy with a rope attached to it.

The current pushed the buoy away. A swift jerk brought it closer, and Patrick and the terrified councillor thankfully grasped its looped ropes.

In addition, a small rowing boat nudged at Patrick’s back, as its owner shipped his oars. Breathless after his quick row towards them, the rower gasped encouragement to both men to ‘’Old on, there, na. Seen you dive in, I did. Soon get you out.’

With the aid of an assortment of idlers, the city councillor was roughly heaved back onto the landing stage, while a panting Patrick hauled himself out.

Sitting on the edge of the stage, Patrick wiped the water from his face with his hands. Then he took his boots off and emptied the water out of them. He examined them ruefully. ‘Should have took them off,’ he muttered to himself. ‘Nobody should try swimming in boots.’

Reclining on the stage, supported by two friendly ferrymen, it seemed as if the councillor spat up half the Mersey River before both he and Patrick were escorted into the nearest warm place, the Pier Head teashop.

The sopping wet councillor was soon seated in the tiny café. A mug of hot tea was immediately proffered him by the startled woman in charge; she kept asking no one in particular, ‘Whatever happened to him, poor bugger?’

Near him stood the owner of the little rowing boat, who had helped to push the pair of them up out of the water. He was nearly as wet as the other two.

In the opinion of the boat owner, this chap in a three-piece suit was obviously a Somebody. Though he did not recollect who he was, it seemed likely that he might receive a decent tip for taking care of a Somebody. So he paid the penny for tea for him, in addition to a mugful for himself.

All attention was focused on the councillor and on the boat owner standing close behind him. It did not occur to anybody in the small crowd of interested onlookers, amongst whom stood the penniless Patrick, boots in hand, that he, also, might be glad of a hot cup of tea; or might even like the chance to mop the water out of his hair with the dish towel quickly produced for the councillor’s use.

While his ruined suit still dripped mournfully over the bare wooden floor, the councillor, aware of who had really rescued him, groggily thanked Patrick. Then, after a moment’s silence, he asked what he could do for him in recompense for his remarkably quick deliverance from drowning.

‘You could have lost your own life – that current is deadly,’ he added, with a hint of respect in his voice.

Looking like a sewer rat newly removed from a drain, Patrick stared at him, nonplussed. He had lost his cap and scarf to the river, and his ill-cut hair draggled over his eyes and down the sides of a gaunt face blackened from years of dust from a multitude of ships’ cargoes.

With an effort, he tried to clear his mind. He wondered if the councillor would consider the replacement of his cap and scarf. Then, as he trembled with exhaustion, the very basic desire of his life swelled up in his mind and expelled any other consideration.

Why not ask? he thought. Why not?

He took a long chance, and whispered almost without hope, ‘If you could get me a regular job, sir…if you could, sir?’ His exhaustion made it difficult to speak.

It was like asking for gold, in a city with thirty-three per cent unemployment. But bearing in mind that this was probably his only chance to talk to a man who might be the equivalent of Father Christmas, he added hastily, ‘And a decent place to live.’

The equally exhausted councillor blew through his lips, and his moustache dripped its last drip.

He turned to the woman behind the counter. ‘Ask this man his name and address and write it down for me,’ he ordered, in a voice still rather weaker than his usual stentorian tone. He turned to the boat owner, and added, ‘And this man’s, too.’

The boat owner smirked with satisfaction.

While the woman hunted in the pocket of her grubby apron for a nub of pencil and then in a drawer for a piece of paper, the councillor turned back to his rescuer and, with a wry smile, said to Patrick, ‘Aye, that’s an ‘ard one, lad!’ He chewed his lower lip for a moment and scratched his wet grey hair, while Patrick waited in almost unbearable suspense. Then he asked, ‘’Ave you got a trade?’

As a member of the City Council, he enjoyed, occasionally, being able to show a little munificence, and here he was, now, seated in front of a small crowd: a good moment. He’d be sure to get his picture in the paper; he had noted that a holidaymaker had leaned over the side of the tied-up ferry to take a snap of him, as he sat on the landing stage. Just now, he had seen the same man at the back of the crowd raise his camera to take another one. He would probably sell the pictures to the Post. Not exactly dignified, he considered, but to have it on the front page of a local newspaper would be useful publicity. And he might, at least, be able to get his rescuer a medal.

Because he had had no breakfast and felt faint, Pat badly wanted to sit down on a nearby stool. He feared to do so, however, because he might offend, by his disrespect, a man who was rich enough to own a gold pocket watch, which still dangled on a chain, secured to a button of his waistcoat.

‘I’m a dock porter, sir,’ he replied, shamefacedly.

‘Humph. Casual? Unskilled, eh?’

‘Yes, sir,’ Patrick muttered. ‘It’s all I could get, ever since I were a kid.’ Then, gaining courage, he added, ‘But I’m strong, sir. I’m a hard worker.’

The councillor nodded, accepted a second mug of tea from the fawning boat owner, and drained it.

‘That’s a real problem,’ he sighed. He was suddenly very tired. He wanted to go home. He glanced again at the forlorn wreck in front of him, and said with compassion, ‘I’ll do what I can, I promise you.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

The councillor knew only too well what being a dock labourer entailed. Casual work was the curse of any port, a nightmare not only to dockers, but also to lorry drivers, warehousemen, victualling firms, anybody who served shipping. Owners wanted a quick turnaround for their ships, whether they were freighters, liners or humble barges; loading and unloading must be done immediately by a readily available workforce, regardless of time of day or night: time and tides waited for no man – and demurrage was expensive. Once the job was done men were immediately dismissed.

For the dock labourers, it meant standing twice a day near a dock, hoping to be chosen for half a day’s employment. Patrick stood at 7 am and again at 1 pm in pouring rain, in broiling sun or on icy January days, waiting, just waiting to be called for about four hours of arduous work.

To draw attention to himself, he would call out his name from amid the jostling crowd. With occasional gifts of tins of tobacco or a packet of cigarettes, he greased the palm of a buttyman, who all too often ignored him and ran his own gang of favourites.

He tried also to be at least recognisable to the shipping companies’ stevedores. When a ship needed a few more hands, over and above those gangs already chosen, this employee of the shipping company would go through the struggling, desperate mob of men, and, with supreme indifference, pick out the extra labourers as if they were cattle being chosen for market. When Patrick was lucky enough to be chosen, he worked steadily and mechanically, hoping that his face might be noted by the stevedore and that he would be chosen again.

His speed of movement did not make him popular amongst his mates. Some of them had a system whereby half of them took an hour off to rest while the other half worked, then vice versa. This doubled the hours of work to be paid for by the shipowner but, to the labourers, it was much less exhausting than doing the heavy work without breaks.

Sometimes, a few men would find an obscure spot in the ship or at the back of a warehouse, and settle down to play cards for half the day, their absence unnoticed amid the general mêlée of dozens of identical-looking labourers unloading a large ship. On paydays, they turned up fast enough to collect their unearned wages.

Even if the shipowners disapproved of it, Patrick was thankful for the rest system, which he felt was fair when doing such an arduous job. He never joined the card players, however, partly because it was blatantly dishonest, and, more precisely, because he was not good at such games and would probably lose most of what he was earning.

He preferred, if he had a few pennies, to play the football pools, where he stood a faint chance of winning thousands of pounds.

In addition, Martha never made a fuss about his playing the pools; like almost everybody else in the court, regardless of the pressing need to pay the grocery bill at the corner shop, she played them herself. Rather than confess this dereliction to the priest, she added an extra Hail Mary to the small penances he usually gave her for any other sins to which she owned up.

Even if he was given work, Patrick collected at the end of the week what could only be described as starvation wages. Or even worse, on mornings when he was not chosen, he would have to go home and admit his bad luck to a hungry wife and children, only to set out again to repeat the whole performance that afternoon.

And thanks to a huge birthrate in the city, thought the councillor as he drank his tea, and a constant migration of even more desperate men from Ireland, there was a great surplus of casual, and, consequently, most satisfactorily cheap, unskilled labour on Merseyside. This fact was not conducive to persuading many of the powerful business interests of Liverpool, or even its City Council, to study methods by which the system could be made more humane. The councillor had himself brought the matter up in council, but the dreadful Depression lying over the whole country made impractical his request for a committee to plan a better system in collaboration with reluctant employers.

Even after two mugs of tea, the councillor was still shivering with cold and delayed shock, so when the waitress handed him the paper on which she had written the addresses, he asked her to get him a taxi. She called a barefoot lad lurking nearby and sent him to find one.

Anxious to earn a quick penny for going to fetch the taxi, the child shot out of the little café and scudded up the incline to the street to hail one.

As they waited uneasily for the vehicle to arrive, Patrick felt that he could no longer stand around in his drenched state. Balancing shakily, first on one leg and then on the other, he put on his sodden boots. He forgot all about the Ark Royal, but the date of its launching reminded him for the rest of his life of the day he met a city councillor.

In an effort to be polite, he now said diffidently to the councillor, ‘I think you’ll be all right now, sir. I’ll be getting home.’

TWO

‘’Aving a Good Natter with Mary Margaret’

May to September 1937

‘And he missed the Ark Royal, he did; and nobody, except the councillor, give no thought to him at all, they didn’t,’ sighed Patrick’s wife, Martha, to her friend and neighbour, Mary Margaret, while they sat on the doorstep of their court house.

They were warmed by a few rays of welcome spring sunshine, sneaking into the tiny court from between the chimney pots. It lit up Martha’s dark visage and birdlike black eyes, and Mary Margaret’s skeletal thinness, which was apparent even when she was wrapped in her shawl.

As they gossiped, Mary Margaret steadily hemmed a pocket handkerchief: on a protective piece of white cloth on her lap, she held a little pile of them, already finished. Beside her, Martha methodically tore up old sheets and folded them into small, neat squares; she would sell the squares to garage hands or to stallholders in the market, so that, from time to time, they could wipe their oily or bloody or fish-scale-encrusted hands.

A month after the rescue, they were once again mulling over Patrick’s unexpected adventure with the city councillor – and, in more detail, his promise to help Patrick get a better job. Help had not as yet materialised.

‘I suppose he must’ve forgot,’ offered Mary Margaret.

Martha smiled wryly. ‘Right,’ she agreed, and then shrugged as if to shake off any wishful thoughts she might have about it.

Mary Margaret Flanagan and her family lived in the back room on the first floor of the crowded court house, in which the Connollys had the front room on the ground floor. She suffered from tuberculosis of the lungs.

Crammed in with Mary Margaret were her widowed mother, Theresa, her four children still at home, and her husband, an unemployed ship’s trimmer.

Because of the lack of a window, her family lived, without much complaint, much of their lives in semi-darkness, relieved in part by a penny candle, when available, and the daily kindness of the two elderly women in the front room of her floor: Sheila Latimer and Phoebe Ferguson left their intervening door open, day and night, so that light from their front window could percolate through to Mary Margaret’s room.

Sheila and Phoebe had been mates ever since they were tiny children. They had shared their sorrows through childhood beatings and sexual misuse, through marriages that were not much better, and, finally, when their husbands had been drowned at sea and their children were either dead or gone, the old chums had decided to live together.

From other inhabitants of the court, they endured a lot of jokes as to their sexual preferences, but they had been through so much together that they did not care. They were thankful for the luxury of a room to themselves, after their earlier experiences of being packed in with children, elderly relations and bullying husbands.

As paupers, they lived on Public Assistance, outdoor relief provided by the City. This, they both thankfully agreed, was a great improvement over the old days, when they could have been consigned to the bitter hardships and tight confinement of the workhouse. Now, as long as no one told the Public Assistance officer about their working, they were able to earn illicitly a little more on the side, by picking oakum, which was used for caulking ships. The oakum picking meant they could buy a trifle more food, and it took them out of the packed house for most of the day. They considered themselves lucky.

Up in the attic, in a single, fairly large room under the roof, lived Alice and Mike Flynn, both of whom enjoyed a certain popularity in the court as a whole, Alice because she was easy-going and Mike because he had a radio.

Mike Flynn was a wounded veteran of the First World War. He had been paralysed by shrapnel in his back and had not been out of their room for years. He lay by the front dormer window, which looked out directly at the window of a similar house across the court. That was all he saw of the world, except for a few visiting birds. He occasionally put crumbs out on his tiny windowsill, which encouraged pigeons and seagulls to land and perch there unsteadily, as they jostled for position.

Mike had been given a radio by a kindly social worker, an ex-army officer. He said it kept him sane. The Flynns’ greatest expense out of their tiny army pension was getting its batteries recharged.

The clumsy-looking box radio, however, brought him unexpected friends. If he was feeling well enough, all the children in the house were welcome to come into the room to sit cross-legged on the bare wooden floor to listen, in fascinated silence, to the Children’s Hour. It might have been broadcast from outer space for all the connection it had with their own lives, but they loved the voice which actually said ‘Hello, children’ and ‘Happy Birthday’ to them.

In addition, their fathers could, sometimes, get early information from Mike regarding the outcome of a football match or a horse race, on which they had bet. Mary Margaret loved nothing better than to listen to the distant music which drifted down the stairs into her room, though her husband, Thomas, grumbled incessantly about it.

Determined to see the bright side, patient Mary Margaret said frequently that it could be worse. The house was not nearly as crowded as it used to be, and, just think, they could be without a roof at all! Or she could be like the old fellow, who lived in the dirt-floored cellar, a cellar which had been boarded up by the City Health Authority as unfit for human habitation.

Martha’s husband Patrick had helped the desperate old Irishman who now lived there to prise the door open.

‘But it’s an awful place to live,’ Martha had protested. ‘Every time it rains real hard, it gets flooded with the you-know-what from the lavatories, and then he’s got to sleep on the steps.’

‘He’s better off in the court than in the street,’ Patrick had argued, and Mary Margaret agreed with him. So Martha shrugged and accepted that you had to help people who were worse off than yourself.

On days when it did not rain, Martha Connolly, Alice Flynn, Mary Margaret Flanagan and her wizened mother, Theresa Gallagher, spent much of their time sitting on the front step, their black woollen shawls hunched round them, as they watched life proceed in the court. As the court was entirely enclosed by houses similar to the one they lived in, all equally crowded, there were plenty of comings and goings on which to speculate.

Until recently, they could have contemplated the midden in the centre of the court and the rubbish which was thrown into it, but the City had had it removed and replaced by lidded rubbish bins outside each house, which were not nearly so interesting to the many rats which infested the dockside.

The almost perpetual queue for the two choked lavatories at the far end of the court was a regular source of amusement. Each person stood impatiently, with a piece of newspaper in his hand, moaning constantly and with increasing urgency at the delay. On the filthy, paved floor of the court, the usually barefoot children of the Connollys and Flanagans relieved themselves in corners, and fought and played. The women intervened only when juvenile fights threatened to become lethal.

‘If you don’t stop that, I’ll tell your dad,’ the women would shriek. This awful threat implied a whipping with their father’s belt on a bare bottom, so it was usually effective.

Ownerless cats and, occasionally, a stray dog stalked rats and mice; and the children found big, dead rats endlessly engrossing.

By the narrow entry from the main street, men stood and smoked and argued. They read a single copy of the Evening Express between them, in order to keep up with the racing news, and also to work on the football pools. Like a ship’s crew, they tried not to quarrel, though not infrequently fist fights did break out. These scuffles, however, were more likely to occur outside the nearby pubs, when, drunk at closing time on a Saturday night, they were emptied out into the street, to be dealt with by the pair of constables on patrol.

Although it was remarkable how a rough kind of order prevailed amid such a hopelessly deprived little community, the younger men enjoyed nothing more than a Saturday night fight, particularly if the two unarmed police constables got involved. It formed a great subject of conversation on a Sunday morning, as they nursed their aching heads and black eyes.

Within the court itself, a family row was high theatre, which brought almost every inhabitant out to watch. When a woman being beaten hit back, the female onlookers frequently cheered her on. ‘Give it ’im, Annie – or Dolly – or May – love,’ they would shriek, joyously adding fuel to male rage.

As the four women sat together on their step, they did not seem to notice the general stench of the airless court or the rarity of a single beam of sunlight. Only when it rained or was too bitterly cold outside, did they seek the lesser cold of Martha’s room, which at least had a window – and a range which sometimes held a fire.

Martha was extremely protective of her frail friend, Mary Margaret. If she had a fire in the range, she would sit her close by it on the Connollys’ solitary wooden chair. She would then boil up old tea leaves to make a hot drink for her, which she laced with condensed milk from a tin. To add to her warmth, she would, sometimes, wrap round her knees the piece of blanket in which her youngest child, Number Nine, slept at night; or she would pat and rub her back when she was struck with a particularly violent bout of coughing.

As they gathered on the step, after the rescue of the councillor, Martha continued her doubts about him.

‘When we never heard nothing, Pat gave up hope, he did, ’specially when he saw the pitcher in the papers of the councillor and the boatman, and nothin’ about himself. And us havin’ to find him a new cap and scarf, an’ all. He lost his old ones when he dive in. And his boots was finished.’

Mary Margaret sighed: the loss of a cap and scarf was indeed serious, the lack of strong boots dreadful.

‘Never mind, love, he were a brave man to do what he done,’ she soothed. She was one of those blessed people who travel without hope, and could not, therefore, ever be disappointed. ‘You have to make the best of it,’ she advised, as she always did. ‘At least, neither of them got dragged under the landing stage by the current.’

‘Oh, aye. If they had, they would have both been drowneded – and without our Pat, it would be the workhouse for us, no doubt about it.’

For a moment, both were silenced by their permanent dread of this fate, despite the recent provision of outdoor relief by the City’s Public Assistance Committee. It was a traditional fear, which ranked close behind their horror of a pauper’s funeral.

Summer turned to foggy autumn and still they heard no more of the councillor.

Patrick grinned cynically, when Martha brought up the subject. ‘It’s to be expected,’ he told her. ‘Why should he remember? Folk like us never waste our time voting.’ He laughed. ‘We don’t mean nothin’ to nobody.’

He continued his usual dockside waits for work; he knew no other world.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.