Полная версия

Stonehenge: Neolithic Man and the Cosmos

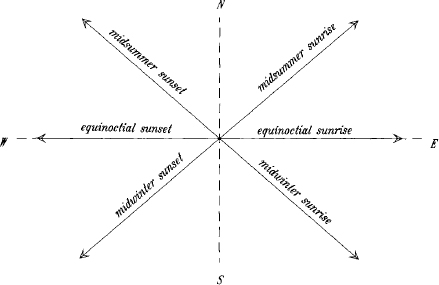

Just as with the stars, I may notice the Sun rising at a recognizable place on the horizon, but in this case, as the days go by, that place will seem to change. In midsummer, the Sun in the eastern half of the sky will rise over its most northerly point of the horizon. It will attain its most northerly point of setting on the horizon’s western half at the same season. I could mark these directions as I did those of the rising and setting star; and as the year progressed and the days shortened, I should notice that those distant points of the Sun’s rising and setting move southwards, and that in midwinter they reach to their furthest points south. Again I could mark those southern extremes in one way or another. The markers (both near at hand, or one near and one distant) would then be aligned on four critical phenomena, namely midsummer and midwinter risings and settings of the Sun.

FIG. 1. The directions of the rising and setting Sun at Stonehenge, around 2000 BC, at the times of summer and winter solstice. The directions for the equinoxes are also marked, but are barely distinguishable from the (broken) east–west line. In all cases it is supposed that the upper limb of the Sun (first or last glint of the Sun) is seen on the distant natural horizon.

Approximately halfway between the directions of sunrise at precise midsummer and midwinter (that is, at the solstices), is the true direction of east; and true west is similarly more or less mid-way between the extreme directions of setting. The actual sizes of the angles depend on various factors, and in particular on the geographical place (or more precisely the geographical latitude) and on the irregularities of the actual horizon. In Fig. 1 the angles are drawn for Stonehenge at a nominal date of 2000 BC. The angles are not precisely divided into equal parts by the east–west line, for reasons explained more fully in Appendix 2.

As early as Neanderthal man—say thirty or forty millennia ago—there were burials aligned accurately east–west, which suggests that some or other celestial body was in the thoughts of those responsible for organizing the rituals of death. A grave excavated at L’Anse Amour, in Labrador, incorporated what were evidently ritual fires arranged to the north and south of the body, which was laid in an east–west direction. The east–west and north–south lines seem to have been key directions in the placement of later burials in many parts of the globe, but—religion apart—how is this tendency to be interpreted? East and west are the directions of the rising and setting Sun at the equinoxes, but they are not easily established, and the positions of the fires might rather be thought to suggest that in the Labrador case the critical directions were north and south, the line having perhaps been decided by the Sun’s midday position. A body with head to the north might have been regarded as lying towards the pole, the region where stars do not move. Granted more sophistication, east and west might have been regarded as midway between the Sun’s extremes of rising and of setting. Alternatively, the four cardinal points of the compass might have been settled not by reference to the Sun but to the daily rotation of the stars: a star culminates (reaches its highest point) on the meridian, just as does the Sun, and the meridian also bisects the directions of a star’s rising and setting. Culminations are not easy to settle precisely, since the altitude of the Sun or star is changing least rapidly then; but this does not mean that culmination was not uppermost in the thoughts of those who chose these directions for burials. Then again, at various periods of history certain bright stars have risen and set due east and west, so that alignment might have been on them. Skeleton directions that have so often been interpreted in solar terms can all too easily be reinterpreted in numerous ways, without our presupposing any particularly sophisticated techniques of observation. Which of these alternatives should one favour?

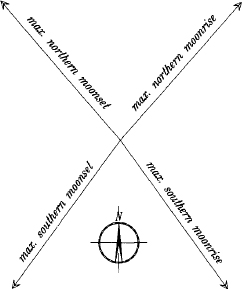

FIG. 2. The absolute extreme directions of the rising and setting Moon at Stonehenge, around 2000 BC, assuming that the Moon is fully visible, and just touching the natural horizon.

The evidence, based not on skeleton positions (which are often dubious) but on the forms of tombs and other structures, is that all of these ways of considering the cardinal points of the horizon, east and west, north and south, are likely to have been familiar in late Neolithic Europe. It is all too easy to become hypnotized by the idea of observation of the Sun and to forget the stars, but there is strong evidence from the period before the first phase of Stonehenge that observation of the stars was then important, perhaps even more important. In some early cultures from which written records survive—in Egypt, for instance—the direction of north was significant, and was found from observations of the stars circling the pole, or of a particular star near the pole at that time. (This was not the star that now serves us as the Pole Star, which in the remote past was well removed from its present position.)

The directions of the Moon’s places of rising on the eastern horizon and setting on the western also change with time, but the pattern of change is much more complicated than in the case of the Sun. The details are put aside for the time being (they are treated more fully in Chapter V and in some detail in Appendix 2), but again there are four absolute extremes of direction, just as with the Sun. The angle separating the northern and southern extremes of the Moon’s rising and setting is greater than in the case of the Sun. The angles in question, which depend as before on several factors, actually fluctuate in the course of time in a way that at first seems erratic. Alexander Thom and others have suggested, however, that the pattern of change lent itself to an analysis of quite extraordinary penetration by the people of the Bronze Age, or even earlier. For the time being, Fig. 2 will suffice to give an idea of the absolute extremes of lunar direction at the latitude of Stonehenge.

The earliest written astronomical records—notably the Egyptian, Babylonian, and Greek—reveal a preoccupation with risings and settings and periods of visibility generally. They show a concern with what was to be observed at the horizon, and with intervals of time between special events in the heavens, and their recurrences. This is not to say that there was necessarily a concern with directions towards points of rising and setting, for there are other ways of using horizon observations. Consider, however, a passage from a Mesopotamian astronomical text compiled early in the first millennium BC and known as MUL.APIN:

The Sun which rose towards the north with the head of the Lion turns and keeps moving down towards the south at a rate of 40 NINDA per day. The days become shorter, the nights longer. … The Sun which rose towards the south with the head of the Great One then turns and keeps coming up towards the north at a rate of 40 NINDA per day. The days become longer, the nights become shorter …

The MUL.APIN text is famous for its catalogue of stars and planets. Although distant in time and place from the Neolithic monuments of northern Europe, the quoted passage provides written testimony to observations of a sort that could well have been made there at a much earlier date. The shifting of the Sun’s place of rising over the horizon was in Mesopotamia related to the rising of stars, or to constellations, distinguished in turn as staging posts along the monthly path of the Moon round the sky. The people concerned worshipped the Sun in various ways, and took the entrance to the land of the dead to be where the Sun descends over the horizon. Many of the writings from which such beliefs are known, in particular the Gilgamesh epic, are much earlier than MUL.APIN, and even antedate the main structures at Stonehenge.

There appear to be no preferred alignments among the numerous Babylonian and Assyrian tombs excavated. In contrast, the alignments of Egyptian pyramids were settled accurately and deliberately, typically towards the four cardinal points of the compass. The interred ruler faced east, while his dependents faced west to the entrance to the kingdom of the dead. Confronted by such utterly different practices among two peoples who simply happen to have left written testimony of their attitudes to celestial affairs, it is on the whole wise to start with a clean sheet, and to base northern practices on northern archaeological remains. Whether there is an element in common to all of these peoples, in the form of a shared psychology, driving them all to found their religions on their common experience of the heavens, is highly questionable. There are certainly a surprising number of patterns of behaviour that many of them have in common, but they are beyond the scope of this book.

What if it should be possible to produce evidence that many prehistoric monuments were deliberately directed towards the rising and setting of Sun or Moon or star? Why devote so many pages to such a trite conclusion? There are some who will consider that the ways in which this was done were remarkable enough to be put on record, but others will naturally hope to draw conclusions as to motivation, whether religious or of some other kind. Does it not follow that the celestial bodies must have been objects of worship? Historians of religion who have come to this conclusion have rarely used orientations as evidence for it. On the other hand, many of those who have written about the alignment of monuments have taken for granted the idea that the motivation came primarily from the need to provide farmers with a calendar for the seasons. The religionists have interpreted isolated symbols found in the religious contexts of birth and death as self-evidently lunar or solar. They have claimed that worship of the Moon would have long preceded worship of the Sun, on the grounds that the tides and the menstrual cycle in women would have pointed to obvious links between the Moon, the weather, and fertility. The calendarists have argued from a supposed practical need, one that they find in evidence in early Greek texts relating the chief points of the agricultural year to events in the heavens. Both lines of discussion have rested far too heavily on intuition. There are a few tentative pointers to Neolithic and Bronze Age religious beliefs to be found from Stonehenge and its surroundings, but they belong to the end of the book, not the beginning.

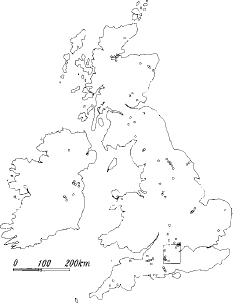

FIG. 3(a) Britain and Ireland, showing (as small circles) the main henges as known at present. The rectangle covers the Stonehenge region as drawn in Fig. 3(b).

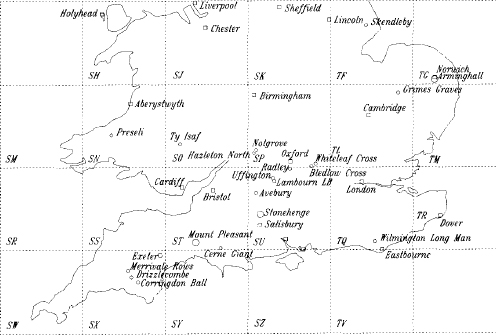

FIG. 3(B) Some of the principal prehistoric monuments of southern Britain, discussed in the following chapters. The rectangular grid (at intervals of 100 km) is that of the Ordnance Survey, and will provide a frame for more detailed maps of the Stonehenge and other regions in later chapters. Small squares mark modern towns.

FIG. 4 A star map for the year 3000 BC, here meant only to introduce the names of the brightest stars then visible from Wessex and mentioned in later chapters. The constellation names will be found in a similar figure in Appendix 2. It should be appreciated that star positions change with time, and that no single map can do justice to them over a period of a century, let alone two or three millennia. Other relevant astronomical matters will be introduced as needed, and the following points are added only for those interested in the type of representation adopted in the figure, which might be used to make rough estimates of visibility. It may be thought of as a movable diagram, in which the stars are moving and the shaded area is fixed. The aperture in the latter, bounded by the horizon circle, represents the visible region of the sky. Circles on the star sphere (such as the equator and tropics of Cancer and Capricorn) all appear as circles on this map, since it is in a projection known as stereographic. Stars are shown graded in size according to their brightness (thus Sirius is much the brightest star in the sky). Stars shown covered by the shading may move into view as the heavens rotate clockwise about the central point, representing the north celestial pole. Whether the stars will then actually be visible will depend on whether the Sun is visible or not. Star maps follow various conventions. Stars can be shown as they are seen looking out from the centre of the star sphere or as they would be seen from the outside of the sphere, looking inwards. The second convention, which is that used on a star globe, is the one adopted here. Had the figure been on a larger scale, scales of degrees could have been added, for instance the equator and the horizon (azimuths). The former graduations would have been uniform, but the latter not. (They would have crowded together more in the lower part of the figure.) The two points in which the tropic of Cancer (the smallest of the concentric circles) crosses the horizon represent the most northerly rising and setting points of the Sun. The most southerly points of its rising and setting are where the horizon meets the tropic of Capricorn (also concentric). The tips of the central cross are in the directions of the four points of the compass, north (below), east (left), west (right) and south (above).

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.