Полная версия

They All Love Jack: Busting the Ripper

An alternative view of this ‘missionary work’ was recorded by a Swedish cleric called Charles Lumholtz in Victoria in 1888: ‘To kill a native of Australia is the same as killing a dog in the eyes of the British colonist.’ Expanding his critique, Lumholtz writes: ‘Your men made a point of hunting the Blacks, every Sunday [presumably after church] in the neighbourhood of their cities … systematically passing the whole day in that sport, simply for pleasure’s sake [his emphasis].’

And what a pleasure it must have been: ‘A party of four or five horsemen prepare traps, or driving the savages into a narrow pass, force them to seek refuge on precipitous cliffs, and while the unfortunate wretches are climbing at their life’s peril, one bullet after another is fired at them, making even the slightly wounded lose their hold, and falling down, break and tear themselves into shreds on the sharp rocks below.’27

Cracking shot, Johnny! Thank you, sir!

‘Although local law (on paper) punishes murder,’ continues Lumholtz, ‘it is in reality only the killing of a white man which is called murder’ (again, his emphasis).

Just who did these Christian civilisers think they were kidding? From which of their Ten Commandments did they consider themselves exempt? You can stuff all that twaddle, old boy. They’re infidels with a different god.

Which unquestionably was true. All tanned foreigners in receipt of British lead were subject to the delusion of a different god (it was only their gold that was real). In India they had one god with three heads, and in England we had three gods with one head: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Consequently, it’s quite likely that God looked more like a British officer with half a bear on his head than a man with a bone through his nose.

Twenty-five thousand black bears a year were slaughtered to make hats for the British Army, and fashionable London ladies liked their hummingbirds skinned alive, a technique which apparently added lustre to the chapeau.28

Meanwhile, back in Africa, where the degraded races wore fur and feathers, white men were endlessly hacking at jungle to get at the loot. This was dark and dangerous territory; the continent was still largely unexplored. It was therefore always possible to face sudden confrontation with wild and dangerous men. There was a high chance, for example, of Sir Cecil Rhodes, or Major R.S. Baden-Powell, suddenly springing upon you from the thicket.

Baden-Powell was one of Wolseley’s breed of chaps, ‘an ambitious little man’ who on the side ‘enjoyed dressing up at concert parties and singing in a falsetto voice’. He was also known to enjoy the company of Boy Scouts.

Powell marched his column of fighting men from the beaches of the Gold Coast into deep up-country, his task once again ‘to bring back the gold’ and to destroy the religious practices of the Ashanti. When they got to their destination, a town called Kumasi, the King of the Wogs was asked to produce 50,000 ounces of gold, and spare us the mumbo-jumbo. Only six hundred ounces were forthcoming, creating a bit of a letdown amongst the visitors, who were already half-dead from the march. Baden-Powell concluded that the King and his mother should be taken back to the coast in default.

No one in Kumasi liked the idea of this, because ‘The Queen Mother, as with many African peoples, was an extremely important figure in the hierarchy.’ Obviously a peculiar lot. Notwithstanding that, Baden-Powell and his boys set about the business of teaching these heathens a history lesson of the type untaught in British schools. In their rage for gold they battered their way through temples and sacred mausoleums, pillaging anything of value in an ‘orgy of destruction that horrified the Ashanti who witnessed it’.

With their royal family as prisoners, the Africans stood by ‘like a flock of sheep’. There was not much for the civilisers to do before bidding their farewells except to ‘set fire to the holiest buildings in town’. ‘The feeling against the niggers was very intense,’ wrote Powell, ‘and the whites intended to give them a lesson they would not forget.’29

Some of them haven’t.

The other side of the continent was of no less colonial interest, but here things weren’t going so well. All the ingredients of a major imperial cock-up were in situ, focusing on a city in the southern Sudan called Khartoum. The Sudan had been annexed by the British, but now they wanted out. On paper this looked relatively easy: bring in the camels, evacuate all the people on our side, get them back to Egypt, and we’ll sort out the details later.

George Eliot’s brilliant aphorism, ‘Consequences are without pity’ – or words to that effect – proved its fidelity here. Before anyone knew it, Khartoum was under a siege that was to last 317 days. An army of 30,000 religious fanatics under the messianic Mahdi, a sort of Osama bin Laden of his day, wanted to kill everyone in Khartoum and take the city back into the bosom of Mohammed. But unhappily, they faced the indomitable might of the British Empire, which in this case was one man. His name was Major General Charles George Gordon.

From time to time I agree with the dead, even with a reactionary conservative politician. After Gordon’s death amid the disaster of Khartoum, Sir Stafford Northcote got on his feet in the House of Commons and told nothing less than the truth. ‘General Gordon,’ he said, ‘was a hero among heroes.’ I find nothing to contradict that. Gordon was a hero, no messing with the word. ‘If you take,’ continued Northcote, ‘the case of this man, pursue him into privacy, investigate his heart and mind, you will find that he proposed to himself not any idea of wealth and power, or even fame, but to do good was the object he proposed to himself in his whole life.’

Gordon’s government betrayed him. As far as the Conservatives were concerned – and again they were probably right – the villain in the whole affair was an irascible old Liberal the serfs had made the mistake of re-electing. Prime Minister William Gladstone was a man of compassion and large mind, but he couldn’t make it up over the Sudan. ‘God must be very angry with England when he sends us back Mr Gladstone as first minister,’ wrote Lord Wolseley. ‘Nothing is talked of or cared for at this moment but this appalling calamity.’30

Wolseley doubtless felt his share of guilt. It was he who had sent Gordon, at the age of fifty, to sort out the problem of the southern Sudan. Throughout the searing heat of that dreadful autumn of 1884 Gordon wrote frequently to London: send us food, send us help, send us hope. Despite the headlines and the Hansards full of unction, the dispatches went unheeded, and Gladstone’s vacillations became the tragedy of Khartoum.

The infidel was closing in, at least to the opposite bank of the Nile. This didn’t cost Gordon any sleep: he had a better God than theirs, and more balls than the lot of them put together. ‘If your God’s so clever,’ he taunted, ‘let’s see you walk across the Nile.’ Three thousand tried it, and three thousand drowned. The rest kept an edge on their scimitars, waiting for the word of the Almighty via the Mahdi. They were a particularly fearsome, in fact atrociously fearsome, mob. According to British propagandists they didn’t give a toss about death, because heaven was its reward. They apparently believed that saucy virgins were going to greet them in Paradise, handing out the wine and honey. I have to say, it doesn’t sound much different from the Christian facility, although our corpses don’t get the girls.

January 1885 baked like a pot. The 14,000 inhabitants left in Khartoum had eaten their last donkey, and then their last rat. Nothing was left to constitute hope but relief from the British, and failing that, death.

‘I shall do my duty,’ wrote Gordon. And he did. There are various accounts of his death, and though this one’s untrue, it’s the first I ever read, in the Boy’s Own Paper fifty years ago. He deserved so romantic an obituary. Death came on the night of 26 January, when thousands of infidels breached the city walls. Upstairs in the palace that was serving as government house, Gordon changed into his dress uniform, combed his hair and donned polished boots. With a revolver in one hand and a sword in the other, he came downstairs to meet them.

They cut off his head and carved him to ham, and we’re back into reality. With his head on a stick they ran around the screeching streets, while the rest of their fraternity went berserk. Just in case there were any shortages in heaven, girls as young as three were raped and then sent to the harems for more. Infants were disembowelled in their mothers’ arms, then the mothers were raped, and their sons were raped. Four thousand were massacred. A piece of human hell. There was no merciful God in Khartoum that night.31

Twenty years later a statue to General Gordon was put up in Khartoum. He may well have smiled at the irony. He was a Victorian hero who hated the Victorians. A few months before his death (irrespective of his fate in the Sudan) he had made up his mind that he would never return to England, writing to his sister: ‘I dwell on the joy of never seeing Great Britain again, with its horrid, wearisome dinner parties, and miseries … its perfect bondage. At these dinner parties we are all in masks, saying what we do not believe, eating and drinking things we do not want, and then abusing each other.’

In another letter, having delineated his view of the difference between ‘honour’ and ‘honours’, he wrote: ‘As a rule, Christians are really more inconsistent than “worldlings”. They talk truths and do not act on them. They allow that “God is the God of widows and orphans”, yet they look in trouble to the Gods of silver and gold. How unlike in acts are most of the so-called Christians to their founder! You see in them no resemblance to him. Hard, proud, “holier than thou”, is their uniform. They have the truth, no one else, it is their monopoly’ (Gordon’s emphasis).32

The Queen never forgave Gladstone, ‘that wretched old madman’, for Gordon’s death, and it was a day of royal celebration when he resigned his office six months later, to be replaced by something more to Her Majesty’s taste.

The man in question was a born aristocrat, a master of chicanery and scandal-management, a barefaced liar – a sort of Margaret Thatcher with class. His name was Viscount Lord Salisbury, and apart from a brief hiatus, he will remain Conservative Prime Minister throughout this book.

The Victorians did nemesis very well. Salisbury didn’t like what had happened in the Sudan any more than Victoria did, and both were prepared to spend whatever it cost for revenge.

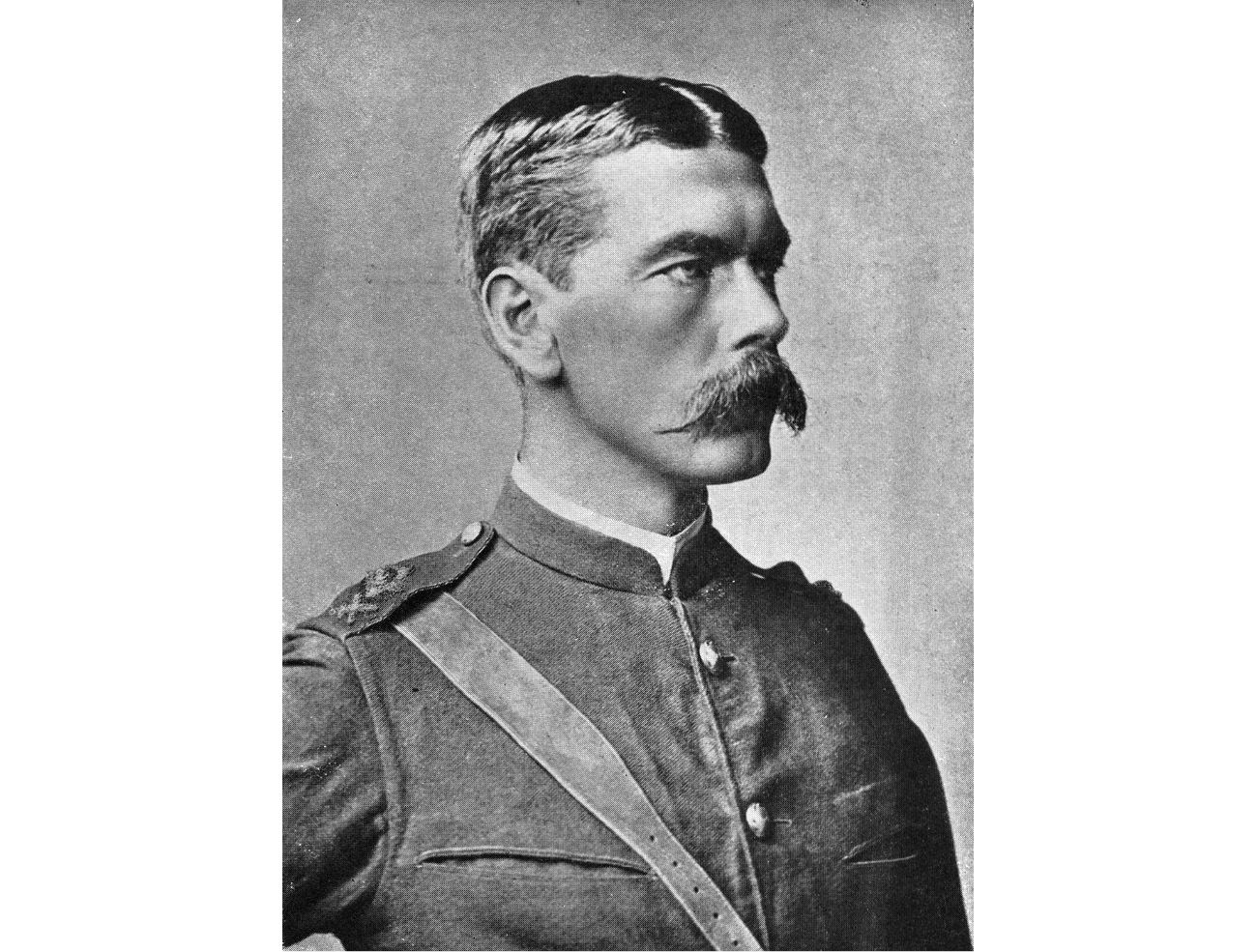

It came a few years later, in uniform of course, in the shape of a forty-seven-year-old man called Kitchener. Although born in Ireland, Herbert Kitchener was a British soldier from the spurs up, fanatically committed to his Queen and country and the death ethic of his time.

‘General Kitchener, who never spares, himself, cares little for others,’ wrote a fresh-faced young soldier who had served under him, igniting fury amongst various old farts in the service clubs. The dispatch had come back to London from Egypt. Its author was a cavalry officer, an incredibly brave young fellow called Winston Churchill, who was augmenting his thin military income as a part-time war correspondent.

‘He treated all men like machines,’ wrote Churchill, ‘from the private soldiers, whose salutes he disdained, to the superior officers, whom he rigidly controlled. The comrade who had served with him and under him for many years, in peace and peril, was flung aside as soon as he ceased to be of use. The wounded Egyptian and even the wounded British soldier did not excite his interest.’33

Kitchener was an imperious bully even when he didn’t need to be. On a previous expedition into British Egypt, he’d been present when some Arab had been tortured to death. He hadn’t liked the look of it, so from then on he carried a handy vial of strychnine in his pocket. He was a weird cove, and a very formidable foe.34

In 1898 Kitchener went up the Nile like a dose of salts, crossed the Nubian desert on a thousand camels and arrived in the Sudan with every intention of sorting the matter out. His army was better equipped than perhaps any other on earth, sporting a relatively new invention of Sir Hiram Maxim, a true masterpiece of homicidal innovation. It was a .303 machine gun capable of firing six hundred rounds a minute, and it was to cost a great number of ‘astral virgins’ their credentials. Kitchener was utterly ruthless towards the enemy, his men, and himself. His campaign ended in a place not too distant from Khartoum, where after savage fighting he took a desert city called Omdurman.

It was here that the Mahdi, responsible for Gordon’s death, was himself interred. Oh, my lord, can you imagine the power of a victorious British General standing in the sun of the Sudan? ‘Why man, he doth bestride the world.’ And like all megalomaniacs, dizzy with the toxins of his own ego, he was about to lose the plot. Like Baden-Powell in his pink bit of Africa, Kitchener freaked out.

Eleven thousand Dervishes lay dead or dying on the battlefield, but there was one man Kitchener wanted to kill again. Despite the years that had passed since Gordon’s death, hate for the man who had caused it still gnawed Kitchener’s heart. The Mahdi’s successor the Khalifa, an ‘embodiment of the nationalist aspirations of the people over whom he had ruled’, had built a magnificent tomb for his predecessor. Though now riddled with Sir Hiram Maxim’s bulletholes it was the full Arabian works, tiled like an astonishing bathroom and topped with a golden dome.

With Allah far from his mind, it was to this shrine that Kitchener went. He dug up the corpse of the Mahdi, and bashed his bones to bits with a hammer he’d brought specially for the purpose. This must have been quite a sight. When the buckets, or whatever, were full, Gordon’s nephew, Major W.S. Gordon, supervised the slinging of this infidel garbage into the Nile, an event the diplomatic language of London described as ‘Removal of the body to elsewhere’. By then, Kitchener had razed the Mahdi’s mausoleum to the ground.35

When news of this retribution seeped out, it didn’t light up the day at Windsor. ‘The Queen is shocked by the treatment of the Mahdi’s body,’ wrote Lord Salisbury, to which the recipient of this telegram, the former British Consul-General of Egypt Lord Cromer, replied that while Kitchener had his faults, when all was said and done, it was a glorious victory, and ‘No one had done more to appease those sentiments of honour which had been stung to the quick by the events of 1885.’

Yes, yes, yes, said the Queen. She liked all that, and was going to hand out some ribbon, but it was getting a terrible press. She felt it was very ‘un-English’, this destruction of the body of a man who, ‘whether he was very bad and cruel, after all, was a man of certain importance’. In her view, it savoured of the Middle Ages: ‘The graves of our people have been respected’, and so should ‘those of our foes’.36

It seemed that filling graves didn’t bother Victoria, it was taking bodies out of them she didn’t like; and it was the trophy of the Mahdi’s skull that particularly flustered her – plus, she’d caught the back end of a rumour that Kitchener had turned it into some sort of flagon, or inkwell, with gold mounts. Kitchener offered various placatory explanations. His original intention, he wrote, was to send the skull to the Royal College of Surgeons (which had apparently gratefully received Napoleon’s intestines). Then he had changed his mind, and for religious reasons he’d rather not go into, had buried the offending cranium in a Muslim cemetery in the middle of the night. The inkwell and the flagon were merely vindictive gossip.

Except they weren’t. I have good reason to question Kitchener’s veracity, and would put serious money on the true destination of the skull, and its purpose.

My explanation will wait.

The question here is, was Kitchener insane? Dragging a putrescent corpse from its grave and bashing what’s left of it to bits with a hammer isn’t normal, except to certain Victorian politicians. In the House of Lords, Lord Roberts said that any criticism of Kitchener was ‘ludicrous and puerile’, which makes one wonder what he would have thought of a gang of Arabs turning up at Canterbury Cathedral with crowbars to heave out the body of St Thomas à Becket.

The Victorian Establishment always had it their own way, and therein lies the answer to my facetious question. Of course Kitchener wasn’t insane. He was one of the most revered officers in the British Army, and would go on doing what he did for another twenty years. He was a Boy’s Own hero, rewarded with a peerage, as Lord Kitchener of Khartoum. A top-hole chap and an intimate of the elite, he was the ruling class. Like his boss Lord Wolseley, and indeed like his King to be, he was an eminent Freemason.

There was no deficiency in this man’s faculties – the exhumation and destruction of the Mahdi’s corpse wasn’t mad cruelty in the passion of battle, it was a calculated and premeditated act. What motivated Kitchener to dig up and violate that stinking cadaver was hate. Hate.

With that hammer in his hand, Kitchener belonged to Satan.

Satan, wrote Milton, ‘was the first That practised falsehood under saintly shew, Deep malice to conceal, couch’d with revenge’.

In the autumn of 1888, no less a personage than Milton’s fearful inspiration was about his business of revenge in London’s East End. Like Kitchener, his intent was premeditated (he too carried a weapon of extreme suitability – not a hammer, but a knife). Unlike the revered soldier, the Ripper’s hate wasn’t so easily satiated. He rehearsed it again and again. And unlike Kitchener, the Whitechapel Fiend had a witty and macabre sense of fun.

There are three things, even at this juncture, that can be stated with reasonable confidence about our ‘Simon-Pure’, as Sir Melville Macnaghten calls him in his monkey-brained book.37

1) He was not a ‘madman’.

2) He was physically and emotionally strong.

3) And the one thing we can be absolutely certain of is that ‘Jack the Ripper’ did not look like ‘Jack the Ripper’.

No fangs. No failures.

Although complaints about underfunding and undermanning were endless, Whitechapel had not a few policemen on the beat. They were in plain clothes and in uniform, and they weren’t up to much. ‘The Chiefs of the various divisions, who are, generally speaking, disgusted with the present arrangement, will sometimes call one of these yokels before him to see how much he really does know. “You know, Constable, what a disorderly woman is?” “No,” said the Constable. The officer went through a series of questions, only to find that the man was ignorant of the difference between theft and fraud, housebreaking and burglary, and his sole idea of duty, was to move everyone on, that he thought wanted moving on.’38

Constable Walter Dew, though perhaps smarter than most, was one of the above. He was a young beat copper at the time of the Ripper. Many years later he published an honest, if occasionally inaccurate, autobiography recalling his memories of the crisis. ‘Sometimes,’ wrote Dew, ‘I thought he [the Ripper] was immune. Was there something about him that placed him above suspicion?’39

You nearly hit the nail on the head, Mr Dew, but it was more fundamental than that. It wasn’t something about the Ripper; I’m afraid it was something about you.

When the Empress proclaimed that ‘No Englishman could commit such crimes,’ there was an implicit corollary. What she actually meant was, ‘No English gentleman could possibly commit such crimes.’

‘The London police regard the frock coat and the silk hat as the appenage of the gentleman, and no one so dressed is ever likely to be roughly handled, even if he forgets himself so far as to dispute a member of the force.’40

Walter Dew couldn’t have seen Jack the Ripper if he had been standing on his big toe. Like a dose of curare, the lethal anaesthetic of class could stop a London copper in his tracks. Murderers and fiends, in this hierarchy of delusion, did not include anyone of a superior social position. Gentlemen only went to the East End to slum it, for a bit of a lark.

Here’s a contemporary description of one such toff: ‘The most intense amusement has been caused among all classes of the London world by the arrest last week of Little Sir George Arthur on suspicion of being the Whitechapel Murderer. Sir George is a young Baronet holding a captaincy in the Regiment of Royal Horse Guards, and is a member of the most leading clubs in town.’

He was also, just in case we haven’t quite got the picture, ‘a great friend of the late Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany’. Anyway, one night – and I’m so tickled I can hardly write it – Sir George joined the ‘scores of young men, who prowl around the neighbourhood in which the murders were committed, talking with the frightened women and pushing their way into overcrowded lodging houses’.

This was obviously topping fun, and providing ‘two men kept together and do not make a nuisance of themselves, the police do not interfere with them’.

It was all a heady wheeze, and now comes the quite delightful dénouement:

He put on an old shooting coat and a slouch hat, and went down to Whitechapel for a little fun … It occurred to two policemen that Sir George answered very much the popular description of Jack the Ripper. They watched him, and when they saw him talking to women they proceeded to collar him. He protested, expostulated and threatened them with the vengeance of Royal wrath. Finally, a chance was given to him to send to a fashionable Western [i.e. West End] club to prove his identity, and he was released with profuse apologies for the mistake. The affair was kept out of the newspapers. But the jolly young baronet’s friends at Brooks’s Club considered the joke too delicious to be kept quiet.41

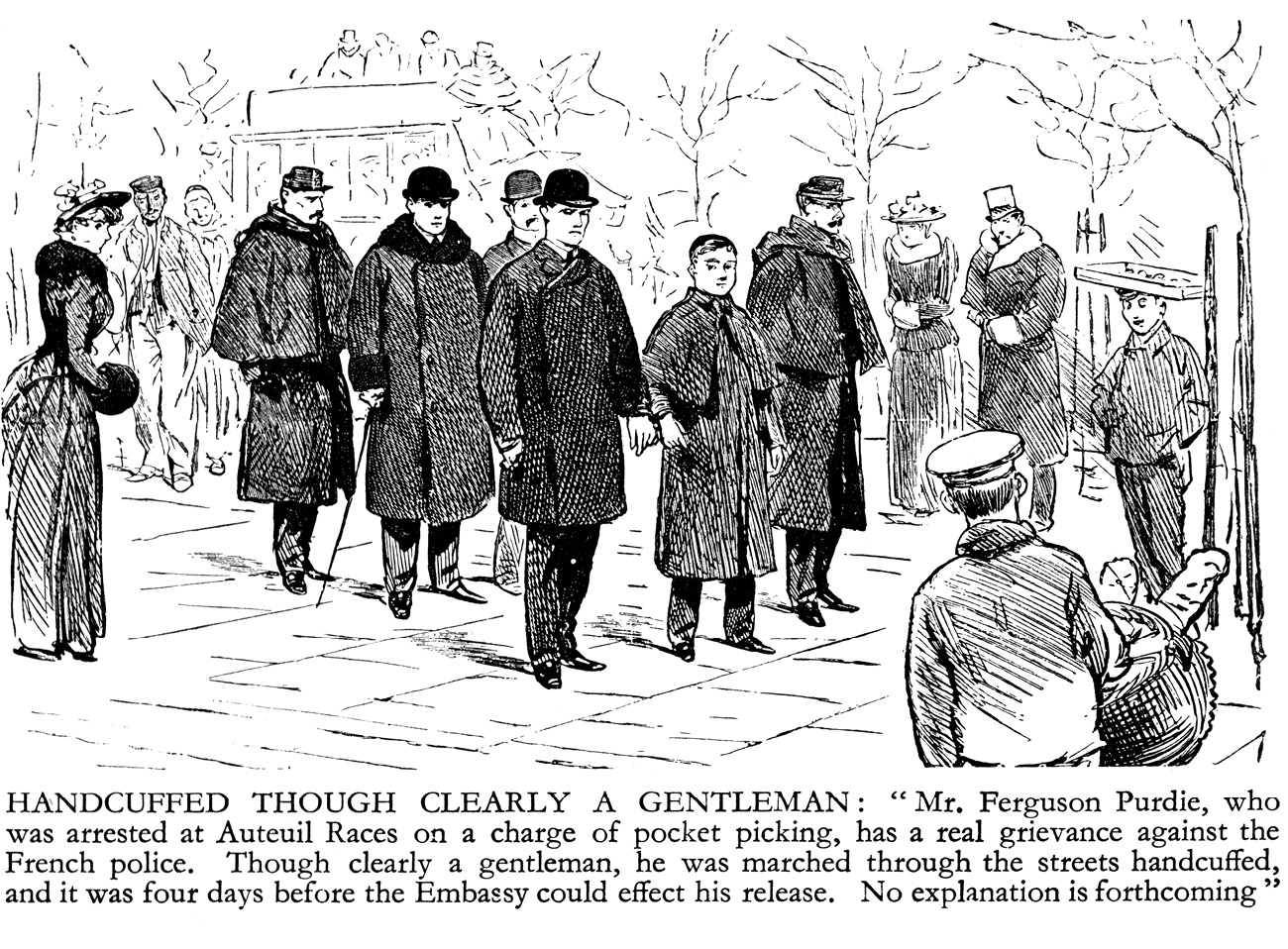

In other words, you only had to flash the Victorian equivalent of a Platinum Amex to get an apology and be on your way. The French Sûreté, infinitely superior to its British equivalent at Scotland Yard, suffered no such upper-crust delusions. ‘Handcuffed Though Clearly a Gentleman’ is the title of this cartoon from 1892. Some English con artist called Ferguson Purdie had been arrested on a charge of pickpocketing at the Auteuil races. The French police had him in ‘cuffs’, and the Illustrated London News went into shock. He was Clearly a Gentleman! All the elements of British class absurdity and wooden-headed xenophobia are encapsulated in this little sketch.

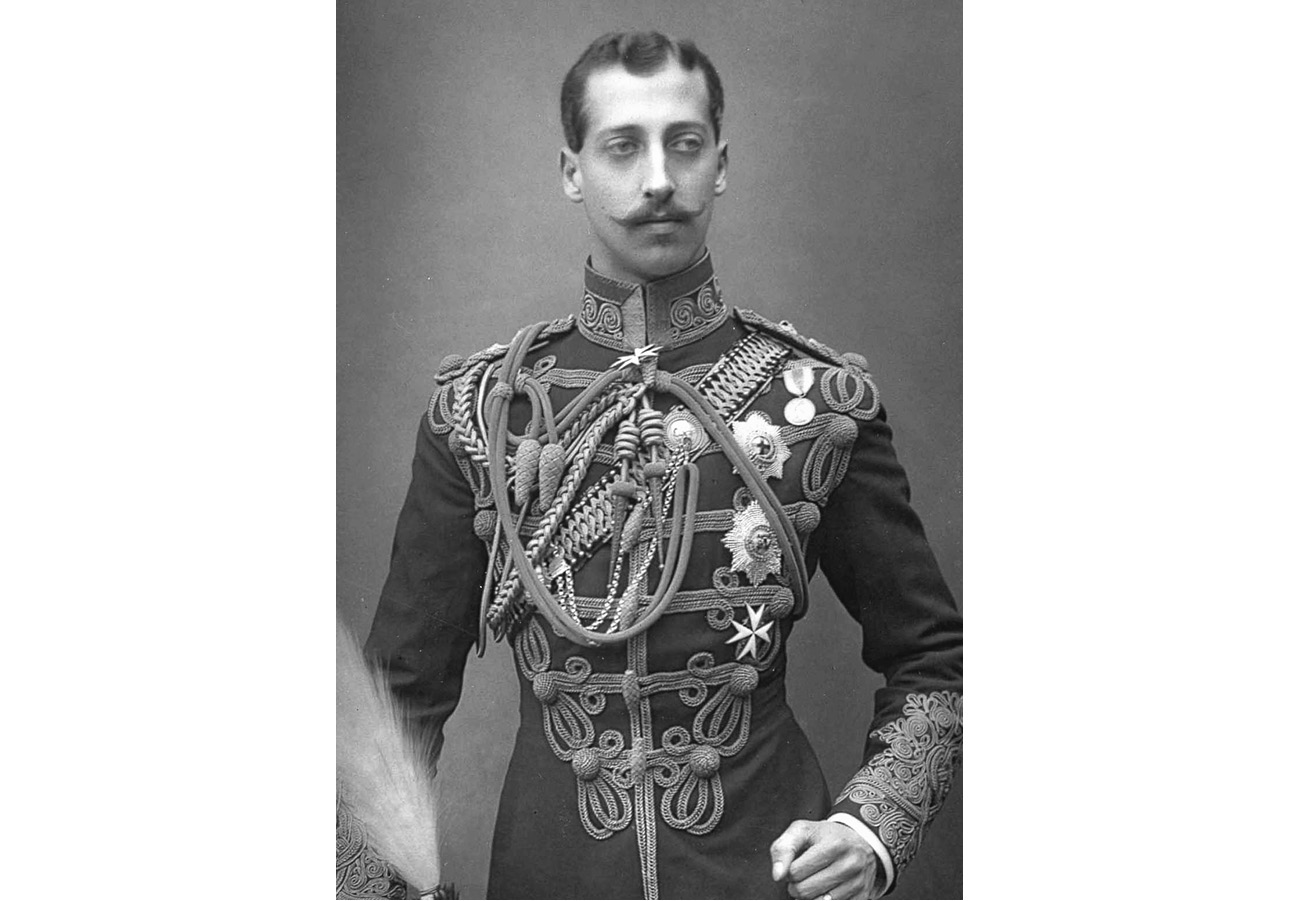

You couldn’t have got more ‘gentleman-like’ than the regal son of that most regal gentleman Edward, Prince of Wales. Prince Albert Victor, Victoria’s grandson and later the Duke of Clarence, one of England’s most eminent Freemasons, used to frequent a male brothel at the house of Charles Hammond, in Cleveland Street in the West End of London. It cost a guinea to sodomise a boy, and as befitted the Prince’s rank, the clientèle were strictly top nobs.

The police had had an eye on the place for some while, keeping a discreet record of the aristocratic comings and goings. Among the officials assigned to this unsavoury calendar was Detective Inspector Frederick Abberline. (He was also on the streets with the Ripper enquiries, and was thus a busy man, of whom we shall be hearing more.)

My interest in Cleveland Street isn’t limited to the sordid activities within, but includes the almost inconceivable criminal activity without. By the late 1880s the Victorian Establishment had become so profligate, so craven, that scandal was hissing everywhere, rupturing through the upper classes like air from a perished ball. Home Office staff were forever being rushed off their feet in a frenzy of patching, and repackaging black as a very dark shade of white. The rules had to be violated, manipulated, cheated and debased. In this case the law had to be made a whore to save the royal arse.