Полная версия

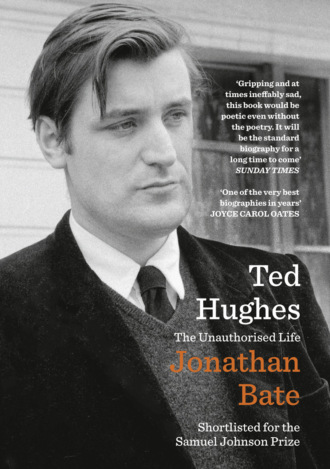

Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life

According to the story, Gerald then digs a grave for the fox. As Ted helps him push the loose soil away, he feels what seems to be a knobbly pebble. When he looks at it closely, it turns out to be a little ivory fox, about an inch and a half long, ‘most likely an Eskimo carving’. He treasures it all his days. He and Gerald conclude that the old lady in the dream was the ghost of the dead fox.

Hughes admits in the preface to his collected short stories that this version of the incident, prepared for Morpurgo’s ghost collection, has ‘a few adjustments to what I remember’. In Gerald’s account, Ted’s dream of the old lady comes the night after they have discovered the body, whereas in the story it is a premonition of the fox’s death. Ted insisted on the reality of the memory, yet neither Gerald nor Olwyn has any recollection of the ivory fox.13 It was only as an adult that Ted began collecting netsuke and Eskimo carvings of animals.

‘The Deadfall’ was the only short story of his later career. He had not written one for fifteen years. Morpurgo’s invitation was an irresistible opportunity to round off his work in the genre. He gathered it together with his earlier stories and made it what he called the ‘overture’ to his writing.14 The camping trip with Gerald in Crimsworth Dene, the dream of the freed fox and the ivory figure that symbolically transformed his lead animal toys into tokens of art came together as his retrospective narrative of creative beginning.

The radio talks for schools that were eventually published as Poetry in the Making give incomparable insight into Ted Hughes, poet in the making. As the boy Ted sculpted his plasticine animals, so the adult writer created poetic images of fox, bird and big cat. In the same way, Ted the teacher found the right voice to capture the attention of ten- to fourteen-year-olds – exactly as his own attention had been caught by Miss Mayne and Mr Fisher.

Early in the second talk, called ‘Wind and Weather’ (there was no shortage of either in the Calder Valley), he suggested that the best work of the best poets is written out of ‘some especially affecting and individual experience’. Often, because of something in their nature, poets sense the same experience happening again and again. It was like that for him with his dreams, his premonitions and his foxes. A poet can, he argues, achieve greatness through variation on the theme of ‘quite a limited and peculiar experience’: ‘Wordsworth’s greatest poetry seems to be rooted in two or three rather similar experiences he had as a boy among the Cumberland mountains.’15 Here Wordsworth stands in for the speaker himself: the deadfall trap in Crimsworth Dene was Ted Hughes’s equivalent of what Wordsworth called those ‘spots of time’ that, ‘taking their date / From our first childhood’, renovate us, nourish and repair our minds with poetry.16

At school, Ted was plagued with the idea that he had much better thoughts than he could ever get into words. He couldn’t find the words, or the thoughts were ‘too deep or too complicated for words’. How to capture those elusive, deep thoughts? He found the answer, he tells his schools audience in the talk called ‘Learning to Think’, not in the classroom but when fishing. Keeping still, staring at the float for hours on end: in such forms of meditation, all distractions and nagging doubts disappear. In concentrating upon that tiny point, he found a kind of bliss. He then applied this art of mindfulness to the act of writing. The fish that took the bait were those very thoughts that he had previously been unable to get into words. This mental fishing was the process of ‘raid, or persuasion, or ambush, or dogged hunting, or surrender’ that released what he called the ‘inner life’ – ‘which is the world of final reality, the world of memory, emotion, imagination, intelligence, and natural common sense’.17

Though a fisherman all his life, Ted did not follow in Gerald’s footsteps as a hunter, despite being an excellent shot. To judge from his sinister short story ‘The Head’, in which a brother’s orgiastic killing of animals leads to him being hunted down himself, he was distinctly ambivalent about Gerald’s obsessive hunting.18 At the age of fifteen, Ted accused himself of disturbing the lives of animals. He began to look at them from their own point of view. That was when he started writing poems instead of killing creatures. He didn’t begin with animal poems, but he recognised the analogy between poetry-writing and capturing animals: first the stirring that brings a peculiar thrill as you are frozen in concentration, then the emergence of ‘the outline, the mass and colour and clean final form of it, the unique living reality of it in the midst of the general lifelessness’.19 To create a poem was as if to hunt out a new species, to bring not a death but a new life outside one’s own.

Like an animal, a living poem depends on its senses: words that live, Hughes insists, are those that belong directly to the senses or to the body’s musculature. We can taste the word ‘vinegar’, touch ‘prickle’, smell ‘tar’ or ‘onion’. ‘Flick’ and ‘balance’ seem to use their muscles. ‘Tar’ doesn’t only smell: it is sticky to touch and moves like a beautiful black snake. Truly poetic words belong to all the senses at once, and to the body. Find the right word for the occasion and you will create a living poem. It is as if there is a sprite, a goblin, in the word, ‘which is its life and its poetry, and it is this goblin which the poet has to have under control’.20

Poetry is made by capturing essences: of a landscape, a person, a creature. In one talk, Hughes suggests that ‘beauty spots’ – he was remembering his childhood places such as Hardcastle Crags and the view from the moors above Mytholmroyd – ease the mind because they reconnect us to the world in which our ancestors lived for 150 million years before the advent of civilisation (the number of years is a typical Ted exaggeration). Poignantly, given that the broadcast went out a year after her death, the example he quoted at the close of this talk was ‘a description of walking on the moors above Wuthering Heights, in West Yorkshire, towards nightfall’ – ‘by the American poet, Sylvia Plath’.21

To capture people, you must find a memorable detail. ‘An uncle of mine was a carpenter, and always making curious little toys and ornaments out of wood.’ This memory of Uncle Albert was all that was needed to create the character of ‘Uncle Dan’ in his children’s poetry collection Meet My Folks!: ‘He could make a helicopter out of string and beetle tops / Or any really useful thing you can’t get in the shops.’22 To invent a good poem, though, you shouldn’t just transcribe your memories. You need to rearrange your relatives in imagination. ‘Brother Bert’ in Meet My Folks!, who keeps in his bedroom a menagerie of every bizarre creature from Aardvark to Platypus to Bandicoot to ‘Jungle-Cattypus’, is an exaggerated version of Gerald (who never kept anything bigger than a hedgehog). But the line ‘He used to go to school with a Mouse in his shirt’, Hughes reassures his listeners, does not refer to Gerald: ‘Somebody else did that.’23 The somebody else was Ted. In the poem, he and Gerald have become one. It was a way of registering his affection for his brother. His feelings about his mother, he admits, were too deep and complicated to capture: she is the one absence from the feast of Meet My Folks!

Think yourself into the moment. Touch, smell and listen to the thing you are writing about. Turn yourself into it. Then you will have it. That, for Hughes, was the essence of poetry.

He ended that seminal opening talk ‘Capturing Animals’ with two personal examples. Late one snowy night in dreary lodgings in London, having suffered from writer’s block for a year, he had an idea. He concentrated very hard and within a few minutes he had written his first ‘animal’ poem. It is about a fox but it is also about itself. The thought, the fox and the poem are one. In the ‘midnight moment’s forest’, something is alive beside the solitary poet. He captures the movement, the scent, the bright eyes. The fox’s paw print becomes the writing on the page. ‘Brilliantly, concentratedly … The page is printed’: it is a captured animal.24

The second example was one of his ‘prize catches’: a pike in a pool at Mexborough.

3

Tarka, Rain Horse, Pike

They moved on 13 September 1938, four weeks after Ted’s eighth birthday. They would stay for thirteen years to the day.1 Olwyn cried for a fortnight and the cat moped beneath a bed upstairs. Ted seemed least affected by the move. He was always adaptable, ready for a new direction. He was immediately enrolled at the Schofield Street Junior School round the corner, getting to know the local boys, some of them shopkeepers’ children, which is what he now was. His best mate was a lad called Swift, mother a greengrocer, father a miner. A neighbouring family had a brutal father, a miner who came home drunk, his face blackened from work. Ted befriended the redheaded daughter Brenda. On Saturday mornings he went to the local ‘flea pit’ cinema and watched Westerns.

The family’s new address was 75 Main Street, Mexborough: a newsagent’s in the centre of a busy mining town, where the bestselling paper was the Sporting Life, to be read daily before placing a bet on the horses. You went into the shop and diagonally to the right was a door to the downstairs living room. Edith and Billie had the front bedroom over the shop. Then there was a big bedroom to the right, over the living room. This had a double and a single bed. A door from here led to a smaller room over the kitchen. Beyond that, there was a room with just a bath. The loo was downstairs and outside. Ted played with his train set in the big bedroom. There was a garage behind, where Ted began keeping animals, notably rabbits and guinea pigs. He cried inconsolably when they died. It was not unknown for him to keep a hedgehog under the sofa in the living room.

Once again, they were overshadowed by a church: across the road stood the ugly red-brick edifice of the St George the Martyr Chapel of Ease to St John the Baptist Parish Church. Its clock had a loud tuneless chime. This was where, six years later, Edith would look out before dawn on D-Day and see crosses in the sky. It was within weeks of their moving to Mexborough that Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned from his meeting with Hitler in Munich and was heard on the radio speaking of ‘peace for our time’.

The business went well. Billie ordered the magazines and the tobacco, and organised the paper rounds. He also took on a concession selling tickets for coach trips. Edith diversified the stock, ordering games, stationery and dress patterns. Gerald and Ted became paperboys. Ted read all the comics and boys’ magazines on the shelves before they were sold. Even his mature poetry would be shot through with a love of super-heroes and an element of zap, kerpow and kaboom.

In later years, Aunt Hilda and Cousin Vicky came down at Christmas. For the children, the whole shop was their Christmas present: each received a pillowcase stuffed with goods, toys, sweets, chocolate.

Gerald struggled to find work locally. He had a brief stint at a steelworks just outside Rotherham, but this was ended by an accident. Then he moved down to Barnet, just north of London, to train as a garage mechanic. He bought a motorbike and started roaring around the countryside, to the consternation of young Ted, who told him he should stick to pedal power. But Gerald’s heart remained in the fields. His favoured reading was the Gamekeeper magazine and it was in answer to an advertisement there that he got a seasonal job as a second keeper on an estate in Devon. This involved rearing pheasants and locating them in the right places to be shot when the 1939 season opened. It was in Devon that he heard Prime Minister Chamberlain on the radio once again, this time announcing that the country was at war with Germany.

The war brought painful memories for Billie and Edith. For Gerald, it began a new life. He returned home at the end of the shooting season, remained there through the ‘phoney war’ and joined up in the summer of 1940. His skill with his hands and experience with engines meant that he was well suited for aircraft repair and maintenance in the RAF. From 1942 to 1944 he was posted to the desert war in North Africa. Gerald’s absence meant that Olwyn and Ted clung close together, sometimes sharing a bed. One of his earliest unpublished poems, witty and affectionate, is called ‘For Olwyn Each Evening’.2

For an adventurous boy such as Ted, there was a thrill in the sound of bombers overhead. Industrial Rotherham, just 6 miles along the river Don, was a target, as was Doncaster, 8 miles upstream. That meant blackouts at night and taped-up shop windows to prevent flying glass. A bomb fell on Mexborough railway station, but Main Street escaped.

Olwyn was a very clever girl. She got a scholarship to the local grammar school. Ted followed in her footsteps in 1941, also winning a county scholarship. Mexborough Grammar was the intellectual making of him. This was where his love of literature matured and began to intersect with his love of nature. In his first year he explored the school library and found Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter. He took it out and kept it, on and off, for two years, until he knew it almost by heart. This became the first of the talismanic books that shaped his inner life.

Williamson’s novel, first published in 1927, had become a bestseller and an acknowledged classic. Because it was written from an animal’s point of view, yet unsentimental and at times extremely violent, English teachers found it especially good to recommend to boys of Ted’s age. The combination of adventure (notably an extended hunting sequence), intricately observed natural history and heightened literary style truly caught Hughes’s imagination at a formative moment in his early adolescence. What especially impressed him was the otteriness of the book, its rigorous refusal to anthropomorphise. Tarka, he explained in a Sunday Times colour supplement article in 1962, is not ‘one of those little manikins in an animal skin who think and talk like men’.3

Hughes was enchanted. It was as if his own life in the fields and among the animals had been recreated in a book. This was the seeding of his poetic vocation. Among the set-piece descriptions that grabbed him was ‘The Great Winter’, which evoked six black stars and a great white one, ‘flickering at their pitches’ like six peregrines and a Greenland falcon, ‘A dark speck falling, the whish of the grand stoop from two thousand feet heard half a mile away; red drops on a drift of snow’. The moon, ‘white and cold’, awaits ‘the swoop of a new sun, the shock of starry talons to shatter the Icicle Spirit in a rain of fire’. Stories are written into the night sky: ‘In the south strode Orion the Hunter, with Sirius the Dogstar baying green fire at his heels. At midnight Hunter and Hound were rushing bright in a glacial wind, hunting the false star-dwarfs of burnt-out suns, who had turned back into Darkness again.’4 Here in embryo are the elements of Hughes’s poetry: the violent forces of nature played out against a cosmic backdrop, figures of myth, creation and destruction, bird of prey, blood on snow, moon, stars, apocalyptic darkness.

When he moved to Devon, Ted got to know Henry Williamson. He sat at his feet and listened to his rambling memories.5 In December 1977, he would deliver the address at a memorial service for the old writer, who had died on the very morning that the scene of Tarka’s death was being filmed for the movie of the book – another of those synchronicities that so fascinated the superstitious Hughes. Speaking to the congregation in St Martin-in-the-Fields on Trafalgar Square, he explained what had inspired him when he found Tarka in the school library all those years before. His first encounter with the book was one of the great pieces of good fortune in his life: ‘It entered into me and gave shape and words to my world, as no book has ever done since. In the confrontations of creature and creature, of creature and object, of creature and fate – he made me feel the pathos of actuality in the natural world.’ This, he said, was a gift of only the greatest writers. Though Williamson did not write in verse, ‘he was one of the truest English poets of his generation’.6

Williamson’s writing was indeed a kind of prose-poetry. Chop up the lines of a passage such as the description of ‘The Great Winter’ and you would almost have a Hughes poem. After all, Hughes did sometimes draft in prose before finding the rhythms of verse: his translations of foreign-language poetry were often versifications of literal prose versions undertaken for him by his friends, while many of the unpublished drafts for Birthday Letters live in a hinterland between journal-writing and poetry.

Tarka the Otter also got him thinking about the role of typography in literature, something in which he would take a keen interest throughout his career, whether in collaborating with his sister and others on private presswork and hand printing, or in complaining to Faber and Faber about their choice of font for a particular poetry collection. When Tarka and the hounds go down to a watery death at the very close of the book, the diminuendo of the typesetting enacts their drowning:

and while they stood there silently, a great

bubble rose out of the depths, and broke, and as

they watched, another bubble shook to the

surface, and broke; and there was a

third bubble in the sea-going

waters, and nothing

more.

Williamson was a Devon writer through and through. Tarka the Otter vividly and exactly evokes the landscape of the valleys of the twin rivers Torridge and Taw that share a North Devon estuary. Shortly after Ted and Sylvia found the house called Court Green, he realised that he had landed upon another spiritual home. On the first day he went fishing on the Taw, at the beginning of the 1962 season, an otter leapt from a ditch and led him to the river. Unawares, Ted had walked into his own ‘childhood dream’, stumbled upon Tarka’s two rivers.7 Later, he would gain riparian rights on the Torridge, at the very spot where Tarka was born. And in the Eighties, when the twin rivers’ otters and fish were threatened by pollution, he spent months and years fighting to save the aquatic life of the estuary.

Just as Tarka the Otter allowed Ted’s readerly imagination to follow brother Gerald to Devon, so Williamson’s war books, encountered later, would give him a way of comprehending his father’s experience of the trenches. He regarded The Patriot’s Progress (1930) in particular as one of the very finest of the many novels and memoirs that came out of the war. The incantatory quality of the prose, the transformation of the day-to-day realities of the soldier’s life into something epic and biblical in cadence again shaped the tones and textures of his own writing: ‘Their nailed boots bit the worn, grey road. Sprawling midday rest in the fields above the sunken valley road, while red-tabbed officers in long shiny brown boots and spurs cantered past on the stubble, the larks rising before them. But the sunshine ceased; and it rained, and rained, and rained. On the sixth day they rested.’8

John Bullock, the protagonist of Williamson’s war novel, is a symbol of England. There is danger here. Disillusionment following the war brings temptation: the search for a strong leader who will clear up the mess, stiffen the national backbone and lead a patriotic march to a New Jerusalem. In the Thirties, Henry Williamson saw such a man in Adolf Hitler. He attended the Nuremberg Rally in 1935 and was inspired by Hitler’s charisma. He idolised Oswald Mosley and became a member of the British Union of Fascists. This would turn him into a pariah in the literary world.

Hughes did not shy away from Williamson’s ugly politics. In his memorial address, he acknowledged that the stories of nature red in tooth and claw came from the same impulse as the fascism. That is to say, from a worship of natural energy that led to a fear (always close to rage) of ‘inertia, disintegration of effort, wilful neglect, any sort of sloppiness or wasteful exploitation’. Williamson’s ‘keen feeling for a biological law – the biological struggle against entropy’ sprouted into ‘its social and political formulations, with all the attendant dangers of abstract language’. His worship of ‘natural creativity’ meant that ‘he rejoiced in anybody who seemed able to make positive things happen, anybody who had a practical vision for repairing society, upgrading craftsmanship, nursing and improving the land’. This reverence for ‘natural’ as opposed to artificial life ‘led him to imagine a society based on natural law, a hierarchic society, a society with a great visionary leader’.9 The trajectory was very similar to that of D. H. Lawrence, whom Hughes would also come to admire. Such ideas, said Hughes, had ‘strange bedfellows’, but who was to say ‘that the ideas, in themselves, were wrong?’ Hughes himself shared exactly this vision of natural creativity and biological law. ‘It all springs’, he said, ‘out of a simple poetic insight into the piety of the natural world, and a passionate concern to take care of it.’ In this, Williamson was an ecowarrior before his time, ‘a North American Indian sage among Englishmen’.10 The lines of correspondence between Green thinking (‘Back to the land!’) and fascism (‘Blood and soil!’) are complex and troubling.11 Hughes, though, was too canny and grounded, too suspicious of the ‘abstract language’ of ideology, to make the fatal move from biocentric vision to extreme right-wing politics.

In the schoolroom, the boys sat on one side and the girls on the other. On winter days, biscuits and little bottles of milk for morning break were thawed on the black iron stove that stood in the middle of the classroom.

Miss McLeod, Ted’s first English teacher at Mexborough Grammar, praised his writing. His mother responded by buying him, second-hand, a library of classic poets. A children’s encyclopedia introduced him to folktales and myths. Rudyard Kipling was the first poetic favourite: the lolloping rhythms, the voicing of animals and the fables of their origins (‘How the Leopard Got his Spots’), the robust and conversational English working-class voices. Ted’s teenage poems, which he was soon publishing in the school magazine, brought Kipling’s style together with the substance of his Saturday-morning viewing of Westerns and jungle adventures. He rejoiced in imitating Kipling’s ‘pounding rhythms and rhymes’: ‘And the curling lips of the five gouged rips in the bark of the pine were the mark of the bear.’12

He also benefited from the attention of his next teacher. Sensitive to both praise and criticism, he showed her his Kiplingesque sagas. She pointed to a particular turn of phrase and said, ‘This is really … interesting … It’s real poetry.’ What she had highlighted was ‘a compound epithet concerning the hammer of a punt gun on an imaginary wildfowling hunt’. Young Ted pricked up his ears. This was an important moment.13 Soon, this second English teacher, Pauline Mayne, would introduce him to more demanding fare: the sprung rhythms and compacted vocabulary of Gerard Manley Hopkins and the challenging obscurity of T. S. Eliot.

There were many happy returns at the end of the war. The towering figure of Gerald arrived on the doorstep in September 1945, to be greeted by a now tall and handsome fifteen-year-old who stared and then, with tears streaming down his face, called out, ‘Mam, it’s him, it’s him!’14 Ted picked up his big brother’s kitbag and in they went for the reunion with Olwyn and their parents. At the grammar school, meanwhile, the masters were returning. Among them, coming out of the navy, where he had served on the North Atlantic convoys, was John Fisher, tall, with a long slim face and a copy of the Manchester Guardian tucked under his arm. Said to be the finest English teacher in Yorkshire, he put on plays, edited the school magazine – in 1947 the sub-editors were Olwyn Hughes and Edward Hughes – and taught poetry with a passion. He had the Bible, Shakespeare and classical mythology at his fingertips. He would sit on the edge of the desk and announce to the class that they were going to study Shakespeare, so they would all be bored to tears. But they never were. He brought wit and wordplay to the classroom, conjuring up Shakespeare’s characters and moving seamlessly between close reading and historical context. Whether it was Wordsworth (whom Fisher especially loved because he was raised on the Cumberland coast) or Wuthering Heights or the First World War poets, he brought the text to vivid life. He would gaze intently as he nurtured the class in the art of practical criticism, but then lighten the tone with some absurd remark (‘The school is now anchored off the east coast of Madagascar’).