Полная версия

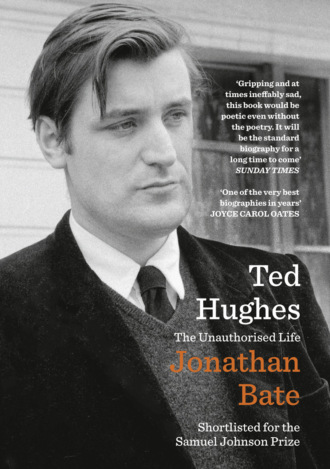

Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life

It is unfortunate that Hughes’s exact words are lost to the record here, but it is clear what he was arguing: that Plath was a symbolic artist persistently misread as a confessional one. He went on to explain:

My struggle has been with the world of people who interpret, try to shift her whole work into her life as if somehow her life was more interesting and was more the subject matter of debate than what she wrote. So there’s a constant effort to translate her works into her life.

Q. And you object to that?

A. It seems to me a great pity and wrong.13

At the time of the Bell Jar lawsuit, Ted Hughes was battling with Sylvia Plath’s biographers – as he battled for much of his life after her death.

Hughes was prepared for this line of questioning. The day before making his Deposition he had phoned Aurelia Plath, Sylvia’s mother. By one of the coincidences typical of Hughes’s life, Aurelia was preparing to give a lecture in a high school later that week on the very subject of how non-autobiographical her daughter’s novel was. Aurelia was ferociously bitter about the autobiographical elements in her daughter’s work. People had accused her of destroying Sylvia and Ted’s marriage, simply on the basis of Plath’s portrayal of her in the enraged poem ‘Medusa’ in her posthumously published collection, Ariel:

You steamed to me over the sea,

Fat and red, a placenta

Paralysing the kicking lovers.14

The conceit of the poem is that ‘Medusa’ is the name not only of the monstrous gorgon in classical mythology but also of a species of jellyfish of which the Latin name is Cnidaria Scypozoa Aurelia. Mother as love-murdering jellyfish: no wonder Aurelia wanted to play the ‘non-autobiographical’ card.

The trouble was, there had been a clause in paragraph 12 of the agreement between the Avco Embassy Pictures Corporation and the Sylvia Plath Estate (that is, Ted Hughes, represented by his agent, Olwyn Hughes) prohibiting any publicity that referred to the film of The Bell Jar as autobiographical. But somehow this clause had been deleted, in an amendment signed by Ted. Letting this go through was a fatal slip on Olwyn’s part. That is why he felt vulnerable in the case, despite the fact that he had in no sense authorised the offending lesbian scenes in the movie. After the awkward fifteen-minute phone call to Aurelia, he agonised with himself in his journal.

Nobody could deny that The Bell Jar was centred on Sylvia’s breakdown and the trauma of her attempted suicide. Hughes accordingly reasoned that he would have to argue that it was a fictional attempt to take control of the experience in order to reshape it to a positive end. By turning her suicidal impulse into art, Sylvia was seeking to save herself from its recurrence in life: she was trying ‘to change her fate, to protect herself – from herself’ but as an ‘attempt to get the upper hand of her split, her other personality, to defeat it, banish it, and, in the end, extinguish it’ it was ultimately a failure.15 The notion of the ‘split’ or ‘other personality’ in Plath was something to which Hughes returned again and again; it was also an obsession of Plath herself, already manifest in her 1955 undergraduate honours thesis at Smith, which was entitled ‘The Magic Mirror: A Study of the Double in Two of Dostoevsky’s Novels’. But these were deep matters, subtle distinctions that would not be easy to make in court. That night, Ted ate swordfish and went to bed early, readied for the encounter with Anderson’s lawyer the following day. In the morning he awoke to the newspaper headline ‘War with Ghaddafi’. His own literary-legal battle was about to begin.

Even as he was resisting the equation of art and life, Hughes was writing (though not publishing) poetry of unprecedented candour about his marriage to Sylvia. The Boston Deposition was a way-station on the road to Birthday Letters, the book about his marriage to Sylvia which he finally published in January 1998. In courtroom and hotel room, he followed Sylvia’s example of turning life into art by transforming the saga of the Bell Jar lawsuit into a long poem, divided into forty-six sections, still unpublished today, called ‘Trial’.

He wrote to his lawyer, to whom he had grown very close, directly after the trial: ‘The whole 24 year chronic malaise of Sylvia’s biographical problem seems to have come to some sort of crisis. I’d say the Trial forced it.’16 Or rather, he added, the synchronicity of the trial and his dealings with Plath’s biographers, of whom there were by that time no fewer than six.

Sylvia Plath’s death was the turning point in Ted Hughes’s life. And Plath’s biographers were his perpetual bane. In a rough poetic draft written when a television documentary was being made about her life, he used the image of the film-makers ‘crawling all over the church’ and peering over Sylvia’s ‘ghostly shoulder’. For nearly thirty years, Hughes and his second wife Carol lived in Court Green, the house by the church in the village of North Tawton in Devon that Ted and Sylvia had found in 1961. Their home was, he wrote, Plath’s mausoleum. The boom camera of the film-makers swung across the bottom of their garden. It was as if Ted and Carol were acting out the story of Sylvia on a movie set, their lives ‘displaced’ by her death.

The documentary crew crawled all over the yew tree in the neighbouring churchyard. Ted wryly suggests that if the moon were obligingly to come out and take part in the performance, they would crawl all over it. Both Moon and Yew Tree had been immortalised in Plath’s October 1961 poem of that title: ‘This is the light of the mind, cold and planetary. / The trees of the mind are black. The light is blue.’ In the documentary, broadcast in 1988, Hughes’s friend Al Alvarez, who played a critical part in the story of Sylvia’s last months, argued that this poem was her breakthrough into greatness.17

Sylvia’s biographers kept on writing, kept on crawling all over Ted. He compares them to maggots profiting at her death, inheritors of her craving for fame: ‘This is the audience / Applauding your farewell show.’18 Hughes was interested in both the theatricality and the symbolic meaning of Plath’s moon and yew tree, whereas the biographers and film-makers worked from a crudely literal view of poetic inspiration. His distinction in the Deposition between the ‘symbolic’ and the autobiographical artist comes to the crux of the matter.

Having studied English Literature at school and university, and having continued to read in the great tradition of poetry all his life, he was well aware of the debates among the Romantics of the early nineteenth century. For William Wordsworth, all good poetry was ‘the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’. Poetry was ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity’. Wordsworth was the quintessential autobiographical writer, making his art out of his own memories and what he called ‘the growth of the poet’s mind’. His friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge, by contrast, though he also mused in verse in a deeply personal voice, argued that the greatest poetry was symbolic, that it embodied above all ‘the translucence of the eternal through and in the temporal’. We might say that Wordsworth was essentially an elegiac poet, mourning and memorialising times past, whereas Coleridge was a mythic poet, turning his own experiences into symbolic narratives by way of such characters as the Ancient Mariner and the demonic Geraldine in ‘Christabel’.

It might initially be thought that Plath was the Wordsworth (her autobiographical sequence Ariel being her version of Wordsworth’s contributions to Lyrical Ballads) and Hughes the Coleridge (his Crow standing in for the Mariner and his figure of the Goddess for Geraldine). Ted Hughes certainly was as obsessed with Coleridge as he was with Shakespeare. But in another sense, Hughes was more of a Wordsworth: he was shaped by a rural northern childhood, by the experience of going to Cambridge, then abroad, then to London. He was the one who followed in Wordsworth’s footsteps as Poet Laureate. Perhaps he was, as an admiring friend of his later years, manuscripts dealer Roy Davids, put it, ‘Coleridge-cum-Wordsworth, and yourself’.19

Seamus Heaney, a more long-standing and even closer friend, began a lecture on Ted Hughes by describing how there was once a poet born in the north of his native country, ‘a boy completely at home on the land and in the landscape, familiar with the fields and rivers of his district, living at eye level with the wild life and the domestic life’. This poet began his education in humble schools near his home, then went south to a great centre of learning. His work was deeply shaped by his reading in the literary canon but also by his memories ‘of that first life in the unfashionable, non-literary world of his childhood’. Convinced of his own poetic destiny, he grew famous and mingled with the rich and the powerful, even to the point of becoming ‘a favourite in the highest household of the land’. But the mark of his lowly beginning never left him: ‘His reading voice was bewitching, and all who knew him remarked how his accent and bearing still retained strong traces of his north-country origins.’20 Heaney then surprised his audience by revealing that this story contained all the received truths about the historical and creative life of Publius Virgilius Maro, better known as Virgil, the ‘national poet’ of ancient Rome. Of course his audience recognised that it was also the story of Hughes. What Heaney did not register at the time was that it is also the story of Wordsworth.21

Later in the talk, though, he did explicitly invoke Wordsworth. The context was a discussion of ‘But I failed. Our marriage had failed,’ the last line of ‘Epiphany’, a key poem in Birthday Letters in which Ted is offered a fox cub on Chalk Farm Bridge. The finality and simplicity of this conclusion, said Heaney, placed it among the most affecting lines in English poetry, alongside the end of Wordsworth’s ‘Michael’ (‘And never lifted up a single stone’). For Heaney, the whole of ‘Epiphany’ answered to Wordsworth’s own requirements for poetry, as laid out in the 1800 preface to Lyrical Ballads: ‘in particular his hope that he might take incidents and situations from common life and make them interesting by throwing over them a certain colouring of imagination and thereby tracing in them, “truly though not ostentatiously, the primary laws of our nature”’.22

One reason why Virgil and Wordsworth and, above all, Hughes meant so much to Heaney, whose signature collection of poetry was entitled North, is that their progression from humble rural origin to great fame and the highest social circles was also his own. He too is the poet described at the opening of the lecture. The transformation of the incidents of ordinary life through the colouring of imagination: this was the essence of Wordsworth, of Hughes and of Heaney.

There is a further similarity between Hughes and Wordsworth. Above all other major English poets they are the two who were most prolific, who revised their own work most heavily and who left the richest archives of manuscript drafts in which the student can reconstruct the workings of the poetic mind. Furthermore, they both wrote too much for the good of their own reputation. Sometimes they wrote with surpassing brilliance and at other times each became almost a parody of himself. Of what other poets does one find oneself saying so frequently ‘How can someone so good be so bad?’

Indeed, what other major poet has been so easy to parody? In the late Sixties, the satirical magazine Private Eye began publishing the immortal lines of E. J. Thribb as an antidote to the dark Hughesian lyrics that filled the pages of the BBC’s highbrow Listener magazine. The fictional poet, ‘aged 17½’, had no difficulty in impersonating the voice: crow, blood, mud, death, short line, break, no verb. Others followed, notably Wendy Cope, with her ‘Budgie Finds His Voice From The Life and Songs of the Budgie by Jake Strugnell’: ‘darkness, blacker / Than an oil-slick … And the land froze / And the seas froze // “Who’s a pretty boy, then?” Budgie cried.’23 Cope has the affection that is the mark of the best parody, which cannot perhaps be said for Philip Larkin in a letter to Charles Monteith, his and Hughes’s editor at Faber and Faber, upon being asked to contribute a poem for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, in which he mischievously and scatologically parodied the language of Crow.24

Larkin, with his grumpy self-abnegating pose, was Hughes’s mighty opposite among the major English poets of the second half of the twentieth century. He liked to tease his rival over his reputed effect on women: ‘How was Ilkley? I am sure you were as big a success there as here. I hope all these stories about young girls fainting in the aisles are not exaggerated.’ And to rib him for his interest in astrology: ‘Dear Ted, Thank you for taking the trouble to send my horoscope which I shall carefully preserve, though I don’t know whether it is supposed to help me or frighten me; perhaps a bit of both. I never thought to ask what time of day I was born, and the information by now is gone beyond recall. I should guess about opening-time.’25

In order to be the object of strong parody, poetry must be memorable. What Larkin and Hughes had in common was the ability to write deeply memorable lines. Though none of Hughes’s turns of phrase has become as famous as one or two of Larkin’s, he is with Wordsworth and Tennyson in the very select company of Poet Laureates who have written line after line that passes the ultimate critical test of poetry, to be once read and never forgotten: ‘His stride is wildernesses of freedom’, ‘It was as deep as England’, ‘a sudden sharp hot stink of fox’, ‘I am going to keep things like this’, ‘Your wife is dead’.26

The argument of this biography will be that Ted Hughes’s poetic self was constantly torn between a mythic or symbolic and an elegiac or confessional tendency, between Coleridgean vision and Wordsworthian authenticity. His hostility to Plath’s biographers was partly defensive – he wanted to protect his children and himself, to stave off the haunting memory of her death. But it was also based on the principle articulated in his Deposition: that it is a great pity and wrong to translate an artist’s works into their life. And yet at the end of his career he finally published Birthday Letters, which became the fastest-selling volume in the history of English poetry precisely because it was a translation of his and Sylvia’s shared life into a literary work. The tragedy of his career was that it took so long for the elegiac voice to be unlocked. But how could that have been otherwise, when the work and death of his own wife were turned before his very eyes into the twentieth century’s principal myth of the fate of the confessional poet?

Hughes spoke repeatedly of the ‘inner life’. And it is the story of his inner life that is told in the documents he preserved for posterity. However, as he observed in an early letter to Olwyn, the inner life is inextricable from the outer: ‘Don’t you think there’s a deep correspondence between outer circumstances and inner? … the people we meet, what happens to us etc., are a dimension of the same and single complication of meanings and forces that our own selves are.’27 His close friend Lucas Myers said that Hughes attended to and developed his inner life more fully than anyone he had ever known, save for advanced Buddhist practitioners. ‘Poetry was the expression and the inner life was the substance.’ But the context of Myers’s remark was Hughes’s material life:

The first poem of Ted’s I saw in draft and easily the least accomplished of any I have seen began ‘Money, my enemy’ and continued for six or seven lines that I do not recall. I think it doubtful that the poem survives. Before I met him, Ted had determined to devote his life to writing. ‘Scribbling’ was ‘the one excuse.’ Or ‘the one justification.’

But money was his enemy because generating it displaced the time and energy needed for the creation of poetry and the development of his inner life.28

The poem ‘Money my enemy’, written when Hughes was in his twenty-fifth year and eking out a living as a script reader for a film company, does in fact survive, because a manuscript of it was preserved by Olwyn. The poet represents his relationship to the world of money in the form of a great war. He imagines his own body cut into quarters, his brain carved up, his hands on the market with the heads of calves and the feet of pigs. Street dogs drag his gut, but his blood – mark of his true poetic vocation – sings of mercy and rest, cradled beneath the bare breast of a woman, satisfied with the food of love.29

Money was the enemy, but it cannot be neglected. Ted Hughes was perhaps the only major English poet of the twentieth century who, despite coming from humble origins, supported himself from his late twenties until his death almost entirely from his literary work. After a period of casual work upon graduating from Cambridge, and a brief university teaching stint in America, he never again had to take a day job as a librarian, teacher or bank clerk in the manner of other poets such as Larkin and Heaney, or for that matter T. S. Eliot.30 His financial endurance was a heroic endeavour, albeit with moments of prodigality. The nitty-gritty of how it was sustained has to be part of the story of his literary life.

Ted Hughes wrote tens of thousands of pages of personal letters, only a small percentage of which have been published, sometimes in redacted form. He preserved intimate journals, appointment diaries, memorandum books, accounts of income and expenditure, annotations to his publishing contracts. The journals are of extraordinary value to the biographer. They were kept very private in Hughes’s lifetime: Olwyn, his sister, agent, gatekeeper and confidante, did not even know that he kept a journal. It must be understood, though, that his diary-keeping was sporadic and erratic. The traces of his self-communion survive in fragmented and chaotic form. There is no equivalent of Sylvia Plath’s bound journals of disciplined self-presentation. Ted’s journal-style writings are scattered across a huge number of yellowing notebooks, torn jotter pads and thick sheaves of loose leaves.

The wealth and the chaos of his thoughts may be glimpsed from an account of just a very few items among the hundreds of boxes and folders of personal papers that were left in his home at his death. There was a box file inscribed ‘Memory Books’, containing prose notes on subjects ranging from Egyptian history and archaeological discoveries, to Hiroshima, to a book about Idi Amin called Escape from Kampala, to the Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi, to sagas, history, and notes for a metamorphic play on the Cromwells. Not to mention the Old Testament king Nebuchadnezzar, a park in West Glamorgan, and the German Romantic poet and short-story writer Bernd Heinrich Wilhelm von Kleist. Another box file, with ‘WISE WORDS’ written on it, contained dozens of prose fragments, diary entries from between 1970 and 1982, episodic passages that seem to be a draft for a first-person story, dreams involving Ted’s children, quotations from books gathered for a planned but never finished ‘Wisdom Book’, photocopies of mind maps for classical subjects, and a drawing of a head with a cabbalistic legend. One could open a folder at random and find within it material as eclectic as a letter about a Ted Hughes impostor, an autograph translation of a poem by the Spanish dramatist Federico García Lorca, and a smoke-stained photocopy of a publicity questionnaire regarding the poet Laura Riding.

At the time of his death, he had already sold tens of thousands of pages of poetry and prose drafts, and many valuable notebooks, to the library of Emory University in America, but he retained a collection of twenty-two notebooks, mostly of pocket size, in which there were over 500 pages of poetry drafts and over 800 pages of autobiographical material, all mingled together. Again, he kept a thick buff-coloured quarto folder bulging with old partially used school exercise books, salvaged to save the cost of buying new notebooks. Here we find reading notes on the eighteenth-century English prophetess Joanna Southcott, the French Revolution, existentialism, China and anti-Semitism, together with thoughts on Sylvia Plath, memories of Frieda Hughes’s birth, accounts of travels in America with Plath, of fishing with her in Yorkshire and going to London Zoo with the children. Precious personal memories are mingled with notes on Albert Camus, a stomach ache, yoga, ghosts, horoscopes, magic, Othello and Macbeth (both Shakespeare’s villain and the poet George MacBeth, who was very involved with Ted’s radio broadcasting), memories of a holiday in Egypt with his second wife, records of dreams in 1962, Scott of the Antarctic, and a visit in January 1964 to the weird woman at Orley House in Bideford. It was into this folder that he slipped an account of the last few days of Sylvia Plath’s life, written within days of her death.

Another filing box was filled with loose sheets organised into roughly chronological sequence and amounting to nearly 500 pages of closely written manuscript prose: self-interrogation, descriptions of places and seasons, reflections on people, events and ideas. This was Hughes’s preliminary attempt to put together a journal.31 Given that he preserved it, the possibility of posthumous publication must have been on his mind.

Using all this raw material, it would be possible to write almost a day-by-day ‘cradle to grave’ account of his life. But the very wealth of the sources would make a comprehensive life immensely long and not a little tedious to all but the most loyal Hughes aficionados. Besides, certain portions of the archive will for some time remain closed for data protection and privacy reasons. The task of the literary biographer is not so much to enumerate all the available facts as to select those outer circumstances and transformative moments that shape the inner life in significant ways. To emphasise on the one hand the travails, such as the nightmare of the Bell Jar lawsuit, and on the other the joyful moments such as the mid-stream epiphany of ‘That Morning’.32

In writing of the inner life, it is sometimes necessary to track a theme, criss-crossing through the years. Subjects such as Hughes’s late work in the theatre, his curatorship of Sylvia Plath’s posthumous works and his obsession with Shakespeare are best treated as stories of their own, rather than scattered gleanings that would all too easily disappear from sight if dispersed across many different chapters. This approach has the added advantage of breaking up the potentially deadening march of chronological fact-listing.

So, for instance, in the summer of 1975, Ted Hughes was farming in North Devon, revising his long poem Gaudete, corresponding and negotiating with his mother-in-law about excisions from Sylvia Plath’s Letters Home, and reading an advance proof copy of Millstone Grit, a memoir of his native Calder Valley by Glyn Hughes (no relation). A strictly chronological biography would gather these four facts in a chapter on 1975. But the significance of the four facts is better demonstrated by placing them in separate strands of narrative: respectively, in chapters on ‘Farmer Ted’, ‘The Elegiac Turn’ in his poetic development, his ‘Arraignment’ by feminists and Plathians, and his own autobiographical ‘Remembrance of Elmet’ (the old name for the Calder district).

The biographer of Hughes faces the peculiar difficulty that he has been portrayed over and over again as Sylvia Plath’s husband rather than his own self. In the United States he is known almost exclusively as ‘Her Husband’ (which happens to be the title of one of his own early poems). This has meant that his marriage to Sylvia is much the best-known part of his life. Because they were barely apart, day or night, from the summer of 1956 to the autumn of 1962, every biography of Sylvia – and they are legion – is in effect a joint life.33 Furthermore, Olwyn Hughes contributed so much to Anne Stevenson’s authorised Bitter Fame: A Life of Sylvia Plath (1989) that it became, as its prefatory Author’s Note put it, ‘almost a work of dual authorship’. Bitter Fame covered the first twenty-three years of Sylvia’s life in just 70 pages, leaving nearly 300 for the seven years with Ted. It was a scrupulously detailed narrative of the marriage, checked for accuracy by Hughes himself. The marriage is also the subject of an entire book: Diane Middlebrook’s sensitive and balanced Her Husband (2004). Elaine Feinstein, meanwhile, in the first biography of Hughes (2001), devoted 125 pages to the seven years from the meeting with Sylvia at that party in Cambridge to her suicide in London, but only 110 to the remaining thirty-five years of Ted’s life. For this reason, my chapters on the years with Plath do not attempt a day-to-day record but focus instead on their joint writing life and on those moments that are caught in the rear-view-mirror perspective of the marriage in the published and unpublished Birthday Letters poems.