Полная версия

Peter Jackson: A Film-maker’s Journey

Bill became a government employee working for the post office – the deal on assisted passages required the émigré to sign a two-year work contract – found accommodation in Johnsonville, a few miles out of Wellington, and joined the Johnsonville Football Club, into which he later enlisted two other British lads who had recently arrived in New Zealand: Frank and Bob Ruck.

In 1951, the Ruck brothers’ sister, Joan, came to Wellington,

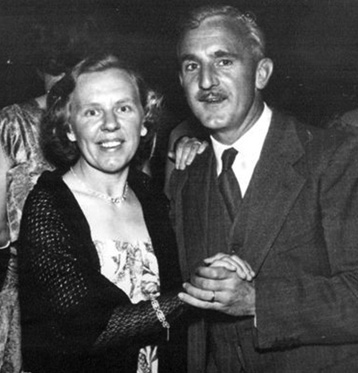

The only hint of any film or theatrics in my family’s background came through my mother, who was a member of the local amateur dramatics club in her home village of Shenley in Hertfordshire, England. Here’s Mum in some melodrama from what looks like the late 1940s.

together with their mother, for what was originally intended to be a six-month visit. After years of war-time rationing and post-war privations, the ‘good living’ promised in those immigration advertisements ensured that an eventual return to Shenley soon ceased to be an option for the future.

Joan got a job at a hosiery factory in the city and whilst attending Saturday matches at the Johnsonville Football Club where her brothers played, met and struck up an acquaintanceship with one of their British mates – Bill Jackson.

Bill and Joan’s friendship blossomed and two years later, in November 1953, they were married and moved to Pukerua Bay, purchasing a small holiday home. The single-storey, two-bedroom house was small, but had a wide uninterrupted view overlooking the ocean and the rugged splendour of the Kapiti coastline.

Taking its name from the Maori word for ‘hill’, Pukerua was founded on the site of a Maori community. Along the side of the hills, which drop sharply to the sea, snakes the precarious track of the Paraparaumu railway line out of Wellington. The area is virtually as unspoilt today as it was fifty years ago, with its wooded and heather-covered slopes; its equitable climate, facing north and protected from the cold south winds by the hills of the Taraura Ranges; and its glorious sunsets that, in the late afternoon, turn sea and sand to gold.

Mum and Dad both emigrated to New Zealand separately and met in Johnsonville.

The year after their marriage, Bill Jackson got a job as a wages clerk with Wellington City Council. Loyal, dedicated and hardworking, he remained an employee of the Council until his retirement, by which time he had risen to the position of paymaster.

After years of my parents trying to have a baby, I finally turned up in 1961. For whatever reason, Mum and Dad couldn’t produce a brother or sister for me.

Born in 1961, Peter was a late child of Joan and Bill’s marriage, and complications during the confinement meant that he was destined to be an only child.

Being an only child and not having anyone else to bounce ideas off, you have to create your own games with whatever props come to hand. You find that you create your fun and entertainment in your own head, which helps to exercise the mind and trains you to be more imaginative…

As an only child – as well as being long-awaited and, therefore, much treasured – Peter was also the sole focus of his parents’ love, care, attention and encouragement. Without sibling companionship or competitiveness, Peter instinctively related to an older generation and, in particular, one that mostly comprised veterans of the 1939–45 war. Peter’s youthful imagination was excited by the overheard reminiscences of his elders and the stories that they told a youngster eager for tales of dangers and heroisms.

The Second World War was the dominant part of their most recent lives. Mum would tell me lots of stories about her life: the air-raids and doodlebugs and her experiences working as a foreman in a De Havilland aircraft factory where they built the Mosquito bomber which was largely made out of wood and was known as the ‘Timber Terror’.

My father didn’t talk as much about his wartime experiences, as I

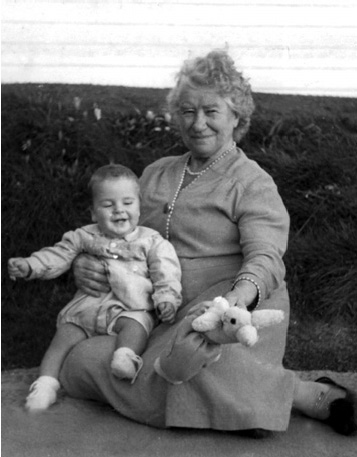

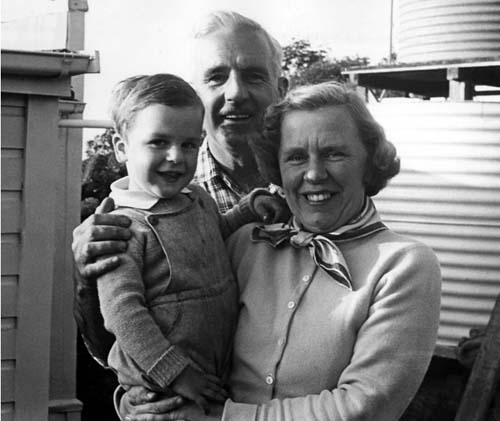

I grew up with Grandma Emma as the matriarch of the family. She taught me to love card games and was a wonderful cook. In her younger years, she was a cook for an upper-class family in London. Upstairs, Downstairs was her favourite show – it was the world she came from. Here she is holding me as a baby. She lived to be 98 and died just as I was making Bad Taste.

would now have liked…He had served with the Royal Ordnance Corps in Italy and, before that, on the island of Malta. This was during the grim years of 1940–43 when German and Italian forces lay siege to the British colony that was of such crucial importance to the war in the Mediterranean and which, as a result, suffered terrible hardships.

Dad spoke about some of what he had seen, but he never really dwelt on the bad things; although he did talk about his time on Malta when, due to enemy blockades and the bombing of supply-ships, the entire island was starving for a period of months and his body-weight dramatically dropped to around seven stone.

He told me the story of the SS Ohio, the American tanker that, in August 1942, was carrying vital fuel to Malta for the British planes when it was attacked by German bombers and torpedoes. Without a rudder, with a hole in the stern, its decks awash and in imminent danger of splitting in two, the tanker was eventually strapped between two destroyers and towed towards the island. Dad was one of the soldiers on the fortress ramparts of the capital, Valetta, when – at 9.30 on the morning of 15 August 1942 – the Ohio finally, and heroically, limped into Malta’s Grand Harbour.

I also heard about the arrival by aircraft-carrier of the first Spitfires in October 1942 and how the 400 planes based at Malta’s three bombsavaged airfields, instantly began an air-defence of the island, flying daily sorties to repel attacks from the German Luftwaffe and the Italian Regia Aeronatica that were based in Sicily.

Enemy aircraft, which were not used to being opposed, were in the regular habit of flying in and beating the hell out of the island – they made some 3,000 air-raids in just two years. On the first raid after the Spitfires had arrived, Dad remembered how he and many others had chosen not to go into the shelters but to stay outside and watch as the bombers roared in across the sea to be greeted by a swarm of Spitfires and the cheers of an island full of people who could, at last, fight back.

But the stories that most excited me – and which led to what has been a life-long interest in the First World War – were those my father would relate about his father, William Jackson Senior. My grandfather joined the British army in 1912 and, when war broke out two years later, was one of the comparatively few professional soldiers amongst the legions of raw conscripts. He went through many of the major engagements of WWI: on the Western Front at the Battle of the Somme; at Tsingtao in China and at Gallipoli, where he was decorated with the DCM (Distinguished Conduct Medal), the oldest British award for gallantry and second only to the Victoria Cross.

The story of the heroic, but ill-fated, struggle on the beaches of the Turkish peninsula of Gallipoli is one of the most dramatic conflicts of the First World War. The combined Allied operation to seize the Ottoman capital of Constantinople, staged in 1915, was a tactical disaster and the price paid by both sides in terms of lives lost and injured was disastrous: more than 140,000 Allies and over 250,000 Turks killed and wounded.

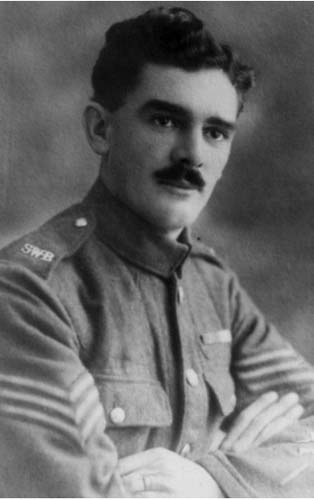

My grandfather served in the British Army, in the South Wales

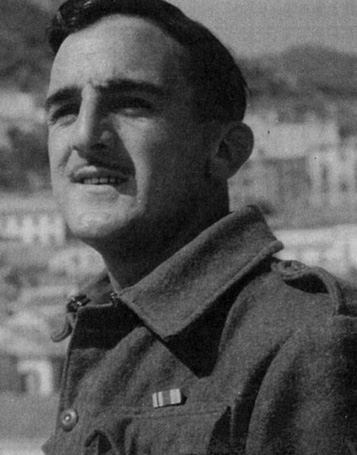

My dad in Malta, 1941. He served in the British Army during the Siege of Malta, suffering the constant bombing and starvation along with the rest of the population. My mother worked at DeHavilland’s aircraft factory, building the Mosquito fighter bombers. I was in the generation who grew up with ‘the War’ a constant undercurrent in our household.

My dad’s father, William Jackson. He was a professional soldier and served in the South Wales Borderers from 1912 to 1919. He went through just about every major battle of the First World War, was mentioned in dispatches for bravery several times, and won the second highest medal, the DCM, at Gallipoli.

Borderers, but I now live in a country where the bravery and tragic losses of the Anzac forces (over 7,500 New Zealand deaths and casualties) are still remembered and annually commemorated. One day, that story should be told on film.

Of course, Peter Weir made a film in 1981 that was set in Gallipoli and starred Mel Gibson; but it was essentially an Australian

view of the conflict. In New Zealand, memories and stories of Gallipoli still hold such a potent place in the history of our country that they deserve to have a good movie made about them. It is not a project that I am pursuing at the moment, but, maybe, one day…

Peter Jackson may well, one day, make a war film – perhaps even one about Gallipoli…In 2003, wandering around Peter Jackson’s Stone Street studios, I came across an extensive scale model of a beach with rising hills. This might easily represent the tortuous terrain of ravines, spurs and ridges that confronted the Australian and New Zealand troops that landed at what is now known as Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915, and where, within the first day’s engagement with the Turks, one in five New Zealanders became casualties of war.

In the same building as the scale model of the beach, sculptors from Weta Workshop were carving the enormous wings, tails and assorted body parts that would eventually be assembled into the huge sculptures of the Nazgûl fell-beasts destined to decorate Wellington’s Embassy and Reading theatres for the premiere of The Return of the King: a reminder that J. R. R. Tolkien, himself a veteran of the Somme, had originally suggested that a suitable title for the third part of The Lord of the Rings would be ‘The War of the Ring’. So, in a sense, Peter Jackson has already made a war-movie, albeit set in the fantasy realm of Tolkien’s Middle-earth.

If and when Peter makes a film based on some twentieth-century wartime event (and it seems inconceivable that he won’t) it will simply be a fulfilment of an ambition that dates back to his debut film, made in 1971 – when he was 8 years old!

The first movie I ever made, which I acted in and directed, was shot on my parents’ Super 8 Movie Camera. I dug a trench in the back garden, made wooden guns and borrowed some old army uniforms from relatives. Then I enlisted the help of a couple of schoolmates and we ran around fighting and acting out this war-movie – or, more accurately, something out of a war-comic – full of action and high drama! In order to simulate gun-fire from my homemade machine-gun, I used a pin to poke holes through the celluloid – frame by frame – on to the barrel of the gun in order to create a burst of whiteness when the film was projected. My first special-effect – and without the aid of digital graphics!

Peter’s earliest recollection of going to the movies was a visit, several years before, to one of Wellington’s cinemas to see a film now long forgotten – and, frankly, deservedly so: Noddy in Toyland. Made in 1957, four years before Peter was born, it had obviously taken its time in reaching the cinemas of New Zealand!

Directed by MacLean Rogers, whose filmography of over eighty titles included many pictures featuring popular radio and musichall stars including the famous ‘The Goons’, Noddy in Toyland was simply a filmed performance of a musical play for children by Enid Blyton.

Based on Blyton’s popular children’s books about Noddy and his friend Big Ears, the author had constructed a rambling and tortuously complicated plot featuring, in addition to the denizens of Toyland,

I remember my childhood as being reasonably idyllic, with lots of family vacations in our Morris Minor. Although I was an only child, I was never lonely – we had a wonderful extended family of uncles, aunts and cousins, most of whom had followed the family migration to New Zealand.

characters from her other books, including The Magic Faraway Tree and Mr Pinkwhistle.

The photography was pedestrian, the stage business dull and laboured – especially without the enthusiastic audience of cheering kids that it doubtless enjoyed in theatres – and the only tenuous link between Noddy’s exploits and the films of Peter Jackson is an encounter with some ‘naughty goblins’ but who, in their baggy tights, were a far cry from the malevolent, scuttling creatures that swarm through the Mines of Moria. Nevertheless, to the young Peter, it was a remarkable film.

I was highly entertained by Noddy in Toyland; it was the first movie that I ever saw and, although I’ve never seen it since, I remember thinking it was pretty amazing!

Seeing a film when I was very young was a big event: we didn’t have a cinema in Pukerua so a trip to ‘the pictures’ meant a car or train journey into Wellington. My parents seldom took me into the city, so the occasional visits to the cinema were rare and special treats and the few films that I saw at this stage of my life tended to make a big impact on my youthful imagination – even if they really weren’t very good!

One such was Batman: The Movie, the 1966 spin-off of the high-camp TV series starring Adam West and Burt Ward, which I saw with my cousins, Alan and David Ruck. I remember being fascinated by the scenes where Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson leapt on to the ‘bat-poles’ behind the secret panel in Wayne Manor in order to reach the Bat-cave. They started their descent wearing ‘civilian’ clothes but, by the time they’d reached the Bat-cave, they were miraculously kitted out in their Batman and Robin outfits.

My cousins were a few years older than me and therefore less impressionable, but I thought that it was just about the most astonishing thing I had ever seen. After the screening, we went back to Alan and David’s house in Johnsonville and I can still remember standing in their dining room and asking, ‘How did they do that? How could they have changed their clothes so fast?’ and my cousin David turning to me and saying, ‘Oh, that’s just special-effects.’

That was the first time in my life I had ever heard the term ‘special-effects’ and I’ve never forgotten the moment that I heard it or who said the words to me. I was 6.

Another early memory of going to the movies was having to stand up while they played ‘God Save the Queen’, which was accompanied by a film of the Changing of the Guard, the Trooping of the Colour or some such ceremony. I’ve never forgotten my cousin Alan winding me up by telling me that if I didn’t stand up, one of the guardsmen would come down and arrest me!

Years later, when I made Braindead, I decided to pay tribute to that vivid memory by beginning the film with the National Anthem and footage of Her Majesty. We had to go through a great deal of red tape to get approval and I can only assume that, somewhere along the line, we must have failed to give them a synopsis of the movie!

Apart from these odd excursions, cinema-going wasn’t a huge part of Peter’s first seven or eight years. The major influences that were to fire his interests and transform them into the passions that would play a part in shaping his future career came, in the first instance, not from the movies, but from television.

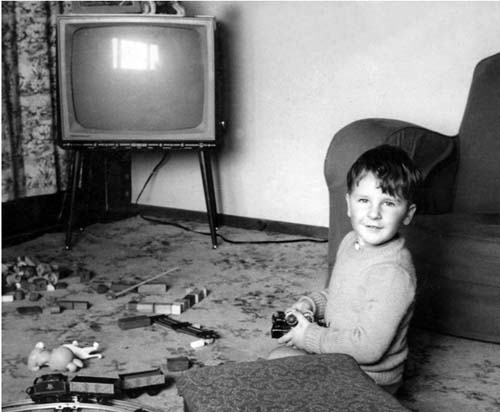

It was 1965 and I was 4 years old when television entered my life. We had been on holiday, and while we were away the TV had been delivered. We returned to find a huge cardboard box in the lounge, and I recall Dad unpacking it and lifting out what would now seem a terribly old-fashioned Philips black-and-white, single-channel television and a set of four legs that had to be screwed on underneath.

It’s difficult for today’s generation to realise just what an impact television had on our lives when we were first exposed to it. I

The arrival of our first television set was my first exposure to escapism – Thunderbirds was screening and I fell in love with model-making, storytelling and fantasy.

initially encountered almost all my adult enthusiasms through ‘the box’.

We used to get all those great old British Fifties black-and-white war movies that my father and I really loved such as Ice-Cold in Alex, Sink the Bismarck, and The Wooden Horse. Dad also loved old silent comedies: I can remember him roaring with laughter at Charlie Chaplin movies, till tears were streaming down his face.

I enjoyed Chaplin, although I wouldn’t describe myself as a fan, but watching his films and those of Laurel and Hardy led me to Buster Keaton and I am most certainly a Keaton fan: I love the dead-pan sense of humour that earned him the nickname ‘Stone Face’, and I really admire his eye for sight-gags and his immaculate sense of timing, particularly the split-second perfection of his stunt-work. I’ve seen all of Keaton’s movies and consider his 1927 picture, The General, to be a work of pure genius. Along with King Kong, The General is among my all-time favourite movies.

Set during the American Civil War, Keaton plays a brave but foolhardy train engineer in the Confederate South, whose beloved locomotive – The General of the title – is hijacked by Yankee troops from the North. Although Keaton was making a comedy-chase movie, it is completely authentic in terms of its period setting. The texture of the world Keaton creates in the film is detailed and realistic and that is something that I always strive to do with my movies.

Keaton was doing comedy while we – with Rings and Kong – have been doing a fantasy; but I honestly believe that even if you are showing outrageous things on the screen – in our case giant spiders, walking trees and huge gorillas or, in Keaton’s case, incredible routines with runaway steam-trains – as long as everything is grounded in a believable environment then it will have greater intensity and more poignancy.

When, years after first seeing The General, I was making Braindead, I’d often try to imagine what sort of gags Buster Keaton would have come up with if – bizarre concept though it is – he had ever made a splatter movie! There’s one particular scene in Braindead that illustrates this perfectly: the hero, Lionel Cosgrove is desperately trying to escape from the zombies; he’s running like crazy and he suddenly realises that he hasn’t actually gone anywhere because the floor is so slippery with zombie-blood that he is just running on the spot! That’s a Keatonish kind of gag.

Old movies aside, the most memorable and influential programme that I remember watching on TV, was undoubtedly Thunderbirds. I loved it! I was a complete, total and absolute fan!

For a generation of youngsters in the Sixties the clarion call: ‘5…4…3…2…1…Thunderbirds are GO!’ was a weekly prelude to fifty minutes of thrill-laden adventures. First aired in 1965, Thunderbirds was the work of pioneering British puppet film-maker, Gerry Anderson, who had already excited young television viewers with such futuristic series as Fireball XL5 and Stingray.

Set in the year 2026, Thunderbirds featured the heroic deeds of International Rescue, a family of fearless action heroes located on a secret island in the Southern Pacific and headed by former moonpilot, Jeff Tracy. The Tracy boys – Scott, John, Virgil, Gordon and Alan – tackled dangerously impossible missions, often pitting their wits against arch-villain and master of disguises, The Hood.

International Rescue had a fleet of fantastic vehicles – rockets, supersonic planes and submersibles – and were aided by the bespectacled boffin, Brains; the chicest of secret agents, Lady Penelope Creighton-Ward and Parker, a former safe-cracker who gave up a life of crime to become Lady Penelope’s butler and chauffeur of her pink Rolls Royce, FAB 1.

The puppets, operated by near-to-imperceptible strings, were given verisimilitude by the use of a technique called ‘Supermarionation’ which used electrical pulses to create convincingly synchronised lipmovements. Thunderbirds married a centuries-old entertainment – the puppet show – with Sixties, state-of-the-art technology; the results were impressive and made compelling viewing.

Many years later, Peter would have the opportunity to meet puppetmaster Gerry Anderson, and in 1997 made an unsuccessful bid to direct a live-action movie version of Thunderbirds (a project that eventually went elsewhere and made a poor critical showing). But in 1965, he was – like millions of other kids – just another devoted young fan…

I loved the big spaceships and was excited by the rescues and the dramatic storylines that now seem incredibly melodramatic! Of course, I knew it wasn’t real; I knew they were puppets and that fascinated me: I wanted to know how they were made and operated.

I remember wanting to make models of the Thunderbirds crafts and buying plastic clip-together model-kits that were around at the time and which I incorporated into my games. Like lots of kids, I had Matchbox toys of various vehicles and I created International Rescue-style scenarios in the garden: cutting a road in the side of a dirt bank that was just big enough for some truck to fit on and then it would be half-hanging over the edge and Thunderbirds would have to come to the rescue!

Setting-up those little backyard dramas with my toys was when ‘special-effects’ really entered my awareness: I knew that was what I’d seen done in Batman: The Movie and that it was what Gerry Anderson was now doing in Thunderbirds; from that point on, I started to have a real interest in special-effects.

It was only when I started discovering what could be done with a camera that I began to think that I might be able to create my own.

The first movie camera I ever saw was a Super 8 camera belonging to my Uncle Ron, Dad’s brother, who would show up at family outings and get-togethers with his camera and shoot movies of us. The earliest movie image of me, shot when I was about 6 years old, shows me walking along a beach with some ice-creams.

Then, happily, my parents acquired a Super 8 Movie Camera! It had come from a neighbour and family friend, Jean Watson, who worked at the Kodak processing lab in nearby Porirua. One year, about 1969, Kodak brought out a really compact movie camera – it was about as simple as it got: just point-and-shoot – and gave their staff the opportunity to buy the cameras at discount. Jean decided to get a camera for my mum and dad, not because at that time I had exhibited any interest in movie-making, but because she thought that my parents might find it fun to be able to capture something of their son’s childhood on film. However, it didn’t take me long to commandeer the camera and, instead of acting out dramas with Matchbox cars and trucks, I was marshalling my friends and filming the Second World War in the back garden!