Полная версия

Pacific: The Ocean of the Future

Praise for Pacific:

‘Winchester does a virtuoso job. … A giant Aladdin’s rug, which he then gamely invites his readers to climb aboard’ New York Times

‘Revealing … delightful … fascinating … highly recommended’ San Francisco Chronicle

‘Fascinating, provocative, and at times, mildly terrifying. … The hallmarks of Winchester’s best work—a fertile, curious mind, impeccable research and command of complex material—are on full display here’ Miami Herald

‘Winchester writes books like someone telling a good yarn around the fireplace … by interweaving history, fascinating trivia, and acute observation’ New York Times Book Review

‘Winchester has a smooth and easy prose style, one that is trustable and clear … He excels at guiding the reader with a contagious sense of wonder’ Boston Globe

‘[Winchester is] a terrific raconteur with a knack for making connections that might have eluded you between events behind the headlines. … Where Pacific opts to go, it goes with savvy and verve’ Seattle Times

‘Winchester has prodigious gifts as a popular historian and an explainer of faraway events’ Los Angeles Times

‘Provocative … and lively’ Wall Street Journal

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

First published in the United States by Harper in 2015

Copyright © Simon Winchester 2015

Jacket design by Gregg Kulick.

Photographs and illustrations © Getty Images

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Simon Winchester asserts the right to be identified as the author of this work

Engraving of the Pacific on title page by Marzolino/Shutterstock, Inc.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780007550777

Ebook Edition © September 2015 ISBN: 9780007550784

Version: 2016-09-20

For Setsuko

Look East, where whole new thousands are!

—ROBERT BROWNING, WARING

Nick Springer/Springer Cartographics LLC.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Praise for Pacific

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

List of Maps and Illustrations

PROLOGUE: THE LONELY SEA AND THE SKY

AUTHOR’S NOTE: ON CARBON

Chapter 1 THE GREAT THERMONUCLEAR SEA

Chapter 2 MR. IBUKA’S RADIO REVOLUTION

Chapter 3 THE ECSTASIES OF WAVE RIDING

Chapter 4 A DIRE AND DANGEROUS IRRITATION

Chapter 5 FAREWELL, ALL MY FRIENDS AND FOES

Chapter 6 ECHOES OF DISTANT THUNDER

Chapter 7 HOW GOES THE LUCKY COUNTRY?

Chapter 8 THE FIRES IN THE DEEP

Chapter 9 A FRAGILE AND UNCERTAIN SEA

Chapter 10 OF MASTERS AND COMMANDERS

EPILOGUE: THE CALL OF THE RUNNING TIDE

Note on Sources

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Simon Winchester

About the Publisher

MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

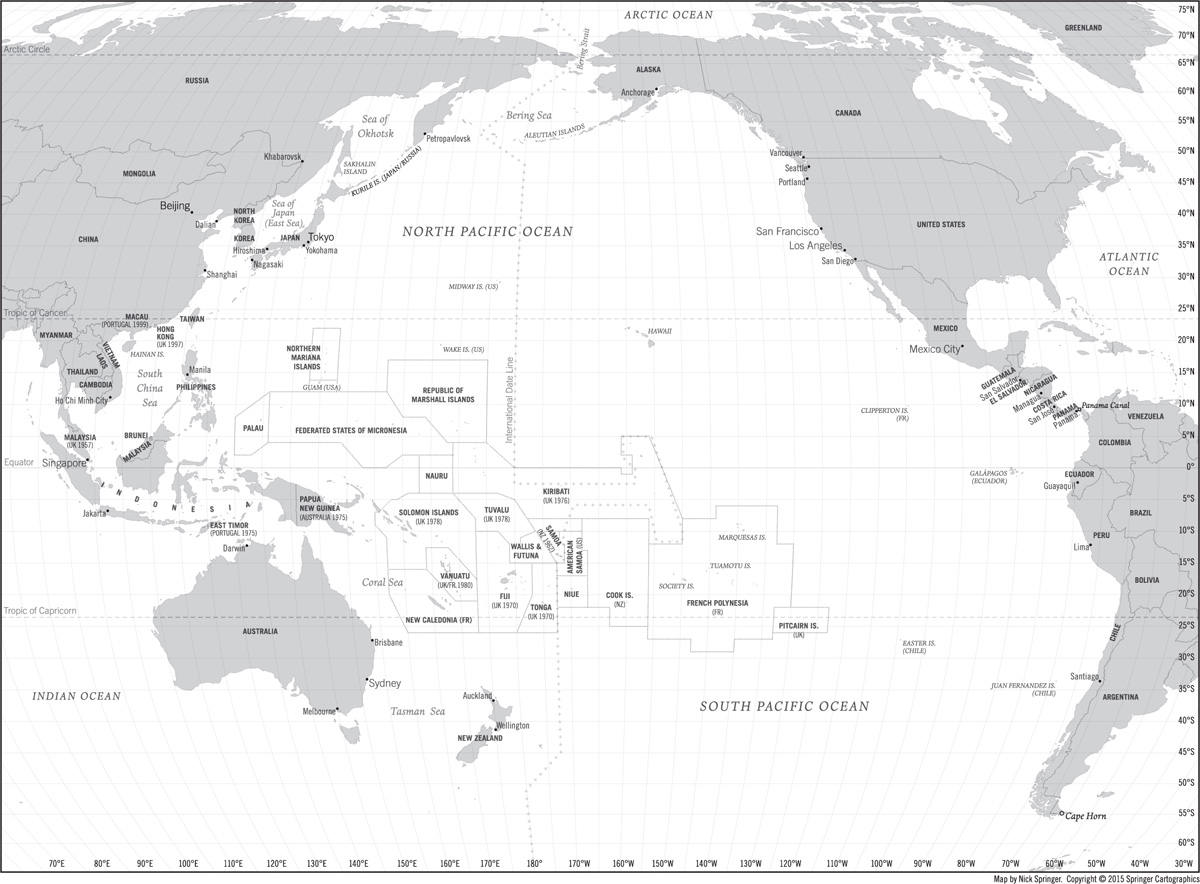

Map of the Pacific—Political

The plutonium bomb Helen of Bikini

Alvin Graves

Masaru Ibuka

Movie poster for Gidget

Duke Kahanamoku

Hobart Alter

Colonel Charles Bonesteel III

The USS Pueblo

The Pueblo’s surviving crewmen, led by Captain Lloyd Bucher

Youngsters’ performance in North Korea

The RMS Queen Elizabeth, in her heyday

The RMS Queen Elizabeth, sabotaged in Hong Kong

Helicopter during the evacuation of Saigon

Hong Kong’s “retrocession”

Destruction by Cyclone Tracy in the city of Darwin

Typhoon Haiyan

Sir Gilbert Walker

Map of the Pacific—Physical

The El Niño Phenomenon

Gough Whitlam

Jørn Utzon

Alvin

The tectonic architecture of the Pacific Ocean

Black smokers

Inhabitants of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef

A Hawaiian feather cloak, an ahu’ula

The short-tailed, or Steller’s, albatross

“The Pacific Garbage Patch”

The eruption of Mount Pinatubo

The carrier USS Kitty Hawk and a Chinese Song-class diesel attack submarine

Map of the Western Pacific: U.S. and Chinese Military

The Nine-Dash Line

Chinese constructions in the South China Sea

The USNS Impeccable

Admiral Liu Huaqing

Andrew Marshall

Hokule‘a

PROLOGUE: THE LONELY SEA AND THE SKY

Here from this mountain shore, headland beyond stormy headland plunging like dolphins through the blue sea-smoke

Into pale sea—look west at the hill of water: it is half the planet . . .

arched over to Asia, Australia and white Antarctica: those are the eyelids that never close; this is the staring unsleeping

Eye of the earth; and what it watches is not our wars.

—ROBINSON JEFFERS, FROM “THE EYE,” 1965

United Airlines Flight 154 leaves Honolulu International Airport just after dawn three times a week, bound ultimately for the city of Hagåtña, the capital of the island republic of Guam. If the northeast trades are blowing at their usual steady twelve knots, the jet will take off to the east, into the low morning sun over Waikiki, and those passengers on the aircraft’s left side will see the wall of skyscraper hotels along the beachfront and be able to glimpse down at Doris Duke’s great seaside mansion, Shangri-La. Once the plane is two miles high above the crater of the dormant Diamond Head volcano, it will begin to make a long and lazy turn to the right.

If the morning haze is light, passengers on the right side now can sometimes glimpse the bombers and heavy transport planes lined up on the flight line of Hickam Field, and maybe a flotilla of sleek gray warships will be gliding slowly through the lochs of Pearl Harbor. There will be some suburbs clustered between the shore and the slopes; there will be a skein of rush-hour traffic crawling along on H-1, the main thruway into Honolulu; and behind these urban images will rise ranges of mountains, razor-sharp aiguilles dotted in places with white radar domes.

With every one of its seats invariably filled, the plane will then clear its throat and tilt its nose ever higher, and once at five miles high, it will set its autopilot to a southwesterly course, heading out initially over two thousand miles of clear blue, unpeopled ocean. As the climb flattens out, and the aircraft passes through a final stratum of small puffballs of cloud, in a blink the island behind fades, is suddenly gone from view, and all below is just sea, endless empty sea, with many hours of emptiness ahead.

The ocean beneath is almost unimaginably vast, and illimitably various. It is the oldest of the world’s seas, the relic of the once all-encompassing Panthalassic Ocean that opened up seven hundred fifty million years ago. It is by far the world’s biggest body of water—all the continents could be contained within its borders, and there would be ample room to spare. It is the most biologically diverse, the most seismically active; it sports the planet’s greatest mountains and deepest trenches; its chemistry influences the world; and the planetary weather systems are born within its boundaries.

Most see this great body of sea only in parts—a beach here, an atoll there, a long expanse of deep water in between. Just a few, mariners mostly, have the good fortune to confront the ocean in its entirety—and by doing so, to win some understanding of the immense spectrum of happenings and behaviors and people and geographies and biologies that are to be found within and on the fringes of its sixty-four million square miles. For those who do, the experience can be profoundly humbling.

Captain Cook wrote that by exploring the Pacific he had gone “as far as I think it is possible for man to go.” To traverse it today, two and a half centuries later—to set a course from Kamchatka to Cape Horn, to pass between the Aleutians and Australia, to make a ten-thousand-mile crossing from Panama to Palawan—is to experience a sense of the frontier that is lacking almost everywhere else on the planet. And not simply for its immensity, but also for the pervasive sense, even today, of confrontation with the unknown and the unknowable. The British Admiralty’s revered chartroom bible, Ocean Passages for the World, still cautions sailors embarking on a crossing, “Very large areas of the Pacific Ocean are unsurveyed, or imperfectly so. In many areas no sounding at all has been recorded . . . the only safeguards are a good lookout, and careful sounding.”

United 154, operated most days by one of the more battered old planes from United’s Hawaiian stable, is known locally as the island hopper, makes its journey along almost six thousand miles, and takes some fourteen shuddering hours to do so. It skitters southwestward, then westward, then northward, stopping along the way at five places—all of them islands, scattered among three different countries—that are even less familiar to most than is Guam’s one city of Hagåtña.

UA154’s first stops, of half an hour or so, are on the flat atolls of Majuro and Kwajalein in the Republic of the Marshall Islands; it then does the same at runways that have been squeezed into the more dramatically mountainous and jungle-draped topographies of the islands of Kosrae, Pohnpei, and Chuuk, in the Federated States of Micronesia.

A scant few passengers travel all the way to Guam. There is much getting off and getting on, and luggage of daunting sizes and bewildering shapes is brought on and taken off at each stop. The crew members, leather-skinned old-timers who have some passing acquaintance with the local island languages, are obliged by United to make the entire journey. They will have recited their seat-belt and tray-table hymns no fewer than twelve times before final touchdown, and seem almost comatose with relief on their arrival in Guam.

In the popular European imagination, the Pacific Ocean contains many of the elements that are to be found along that six-thousand-mile passage between Honolulu and Hagåtña. In every stopping place, it is invariably warm, tropical; both the sea and the sky are intensely blue, the air is sweetly breezy, and there are white sands and coral reefs and sparkling fish of vivid colors darting between the anemone fronds. The roads are decked with bougainvillea and flamboyants and orchids and parrots, with papaya trees and palms of incredible profligacy that drip with dates and bananas and coconuts. Palm trees are central to Pacific imagery: they are to be seen leaning slightly off the vertical, under the endless press of the trade winds, and thereby offering a picture-perfect and theatrically green backdrop for every beach scene; a frame for other equally familiar images of curling waves and spume; or as a border to an empty ocean panorama with its distant gatherings of surfers waiting patiently for the rollers to break and the seas to begin to run.

Such is in evidence everywhere, at every stop, on the United island hopper’s run. Hawaii, the starting point, is of course the quintessential exemplar of the mixing of what outsiders see as Polynesian magic and transpacific migration. From Polynesia there is the plangent sound of the ukulele, the sight of the grass skirt, the blossom in thick black hair tipped behind the ear, the nut-brown skin, the dancing, the dancing, the dancing.

Yet when I lived for a while in Manoa, on the eastern side of Honolulu City, it was not so much Polynesian culture that lapped into every corner of my life as the cultural influences of the farther side of the Pacific Ocean.1 There was a Japanese grocery store down the street, a Burmese restaurant next door, and every other person on the bus seemed to be from Manila. I kept hearing Korean spoken in the elevators, and met Chinese migrants in the most unexpected places: the elderly man who cut what remains of my hair was from Kowloon, and had been a waiter for decades on the Coral Princess, a Hong Kong–flagged liner that once shuttled between Sydney and Tokyo, by way of Jakarta, Port Moresby, Manila, and Shanghai.

Nonetheless, Polynesia rather than Pacific Asia is the current preferred affect of Hawaii. Polynesia is the impression one likes to carry away, as the islands fade astern or over the horizon. Hula, luau, aloha, lei, ohana—the best-known words from a lexicon constructed from the thirteen letters of the Hawaiian alphabet—hear them, and you know in an instant which ocean you’re in.

This place—though an American state since 1959 (the other Pacific state, Alaska, was similarly admitted almost eight months before), and much changed as a consequence—is still in its perceived cultural essence the Pacific of its Western devotees. Hawaii manages still, deep down, to evoke some of what was felt by Gauguin during his time in the Marquesas, or by those who brought Omai of Ra’iatea to London, or by those gently compassionate scholar-administrators such as Arthur Grimble, famed for his once-favorite memoir of Pacific life, A Pattern of Islands.

Hawaii’s shopping malls and warplanes and mountaintop telescopes and aircraft carriers and its legions of resident oceanographers and meteorologists may give the impression that the islands have fully entered and embraced the modern era. Yet, culturally, Hawaii is still Polynesia, linked firmly to Easter Island and the Cook Islands and Aotearoa (“the Land of the Long White Cloud”), New Zealand. Hawaii, for all its apparent intimacy with the American mainland, still resonates with the old Pacific stories of Herman Melville, of Robert Louis Stevenson. It is still emotionally connected to the Pacific that so enchanted poets such as Rupert Brooke, who spent seven idyllic months two thousand miles farther south, in Tahiti, and memorialized it in lines that, once heard, are long remembered:

Taü here, Mamua, Crown the hair, and come away! Hear the calling of the moon, And the whispering scents that stray About the idle warm lagoon. Hasten, hand in human hand, Down the dark, the flowered way, Along the whiteness of the sand, And in the water’s soft caress, Wash the mind of foolishness.

They may well be. But the Pacific of Brooke’s “soft caress” is soon swallowed up as United 154 soars ever westward each morning, into what swiftly becomes much darker territory—both metaphorically and actually.

Some fifteen hundred miles on from Honolulu, the flight crosses the International Date Line, and the day on board is instantly transmuted into tomorrow. Wristwatch date windows have to be changed, and diary pages flipped forward; the shadows at each airport stop lengthening, so the next day’s afternoon steadily begins to take over from the past day’s morning.

The date line, a necessary evil for maintaining a system of timekeeping in a spheroidal and interconnected world, was originally set down here, right in the middle of the Pacific. It could have arrowed straight from north to south, like an antimeridian to Greenwich, on the opposite side of the globe; but since it was going to make calendric mayhem in whatever populated place it passed through, the delegates to the International Meridian Conference, held in Washington, DC, in 1884, designed it to zigzag this way and that around the islands and minor republics and kingdoms that got in its way, or were near to it.

At the time this was done, the Pacific was a commercially comatose expanse of sea, with neither aircraft nor telephone cables in place, its international trade limited mainly to the peddling of copra, whale oil, and guano. The existence of an ephemeral line that magically decreed it to be noon on a nonworking Tokyo Saturday while it was still breakfast time on a potentially busy California Friday had scarcely any effect on such matters as the trade in guano futures. In the days long before arbitrage became all the rage, the date line was no more than an idle conceit, something for the stewards on long-haul ships to tell their passengers, who found “gaining a day” or “losing a day” to be greatly amusing.

Today, however, when snap decisions in Japan can urgently affect financial doings in San Francisco, the line has become something of an inconvenience. A Friday decision can’t always be made, because where it needs to be made, it is Saturday. It need not have been so: back in 1884, because of arguments over the siting of the prime meridian, with the apoplectic French naturally opposed to its running through a suburb of London, a genial Canadian time zone expert named Sandford Fleming suggested that the prime meridian be placed in the middle of the Pacific instead, and the date line made to run from pole to pole, where the Greenwich line does today. His idea was ridiculed; but today some few remember him fondly, and would also like to see the date line moved into the Atlantic, to minimize the nuisance it causes in the commercially busiest ocean in the world.

Yet this is no more than technical stuff. There is quite another kind of darkness into which United 154 flies, a more metaphorical darkness, and one that helps paint a rather fuller picture of today’s Pacific Ocean.

Once across the line, the plane leaves the ethnic limits of Polynesia. The Marshall Islands, of which Majuro is the capital, are part of the sprawling archipelagos of Micronesia. Together with the prettily named Carolines and the Marianas, these hundreds of small islands in the northwestern quadrant of the ocean—some of them tall and volcanic; most of the Marshalls low atolls of coral, and lethally vulnerable to the ever-rising seas—present en bloc a troubling example of the recent history of the ocean and its people. Of what can happen to a place and a population subjected to the casual exploitation of foreigners who, all too frequently in recent centuries, have seen the ocean’s immense blue expanse as having been created for their convenience alone.

For the islanders, it has been a bewildering cavalcade of misfortune. The populated specks of Micronesia have existed under perhaps the most complex colonial history of anywhere in the ocean. This ancient and settled culture first felt the impress of outsiders in 1521, when Magellan landed in the Marianas and predestined Guam’s seizure by Spain—leading to the establishment there of the very first formal European possession in the Pacific. The oldest native civilization in the region, the Chamorros—who had migrated from Southeast Asia as many as four millennia before—were all but destroyed, either by illness or at the hand of these European invaders. Their numbers dwindled to just a few thousand; their language briefly teetered on the edge of oblivion. And yet the sad saga of Micronesia had only just begun.

Germany was next in line to take an interest in the region, driven first by the needs of commerce and then by the pressing demands of pride, expansion, and empire. Spain initially balked at the impertinence of a Northern European rival trying to muscle in on its territory, but eventually acquiesced, and by the end of the nineteenth century, the Marshalls and the Carolines, settled by German traders who established copra and cotton plantations there, came to be administered by German governors. They were protected by a blue-water navy of sorts, the German East Asiatic Squadron, a cruiser force of six ships that eventually settled a fixed base in the docks of Tsingtao,2 in China’s Shandong province.

Meanwhile, in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, the United States opted to take Guam from Spain, and placed a coaling station there for the convenience of its own fleet. To add to this confusing amalgam, Britain began to nibble away at the eastern parts of Micronesia and took the Gilbert Islands for its own, together with the Ellices, which were nearby (though ethnically Polynesian, like Hawaii and Tahiti and points south and west).

Thus might this cumbersome patchwork of island disarrangement have long remained, but for the outbreak of the Great War. Japan had joined forces with Britain from the very beginning of the conflict, and its navy moved quickly to police the sea-lanes of the western Pacific, at the very least to stop all the German trade there. An immediate task was to chase away the German navy and to occupy what some in Tokyo saw as the commercially interesting and strategically important Micronesian islands. By October 1914, Japanese forces had almost all the islands firmly under their control—with long-term implications that would become much clearer only in the aftermath of the Second World War.

This was to be the third formal occupation of Micronesia. Tokyo newspapers of the time regularly showed photographs of bearded and be-medaled Japanese governors opening sugarcane mills and schools and railway lines on island after island. Such images fed into a general Japanese affection for Nan’yō, the South Seas, and almost certainly helped foster the belief in Japan’s inherent right to govern an even larger part of the region—governance that would eventually be employed, as it happened, for a wider and more sinister purpose. “It is our great task as a people to turn the Pacific into a Japanese lake,” cried a noted historian and Diet member, Yosaburo Takekoshi, toward the end of the Great War. “Who controls the tropics controls the world.”