Полная версия

Nein!: Standing up to Hitler 1935–1944

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018

Copyright © Paddy and Jane Ashdown Partnership 2018

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008257040

Ebook Edition © October 2018 ISBN: 9780008257057

Version: 2018-08-28

Dedication

To Hans Oster, preux chevalier

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

List of Illustrations

Epigraphs

Introduction

Main Dramatis Personae

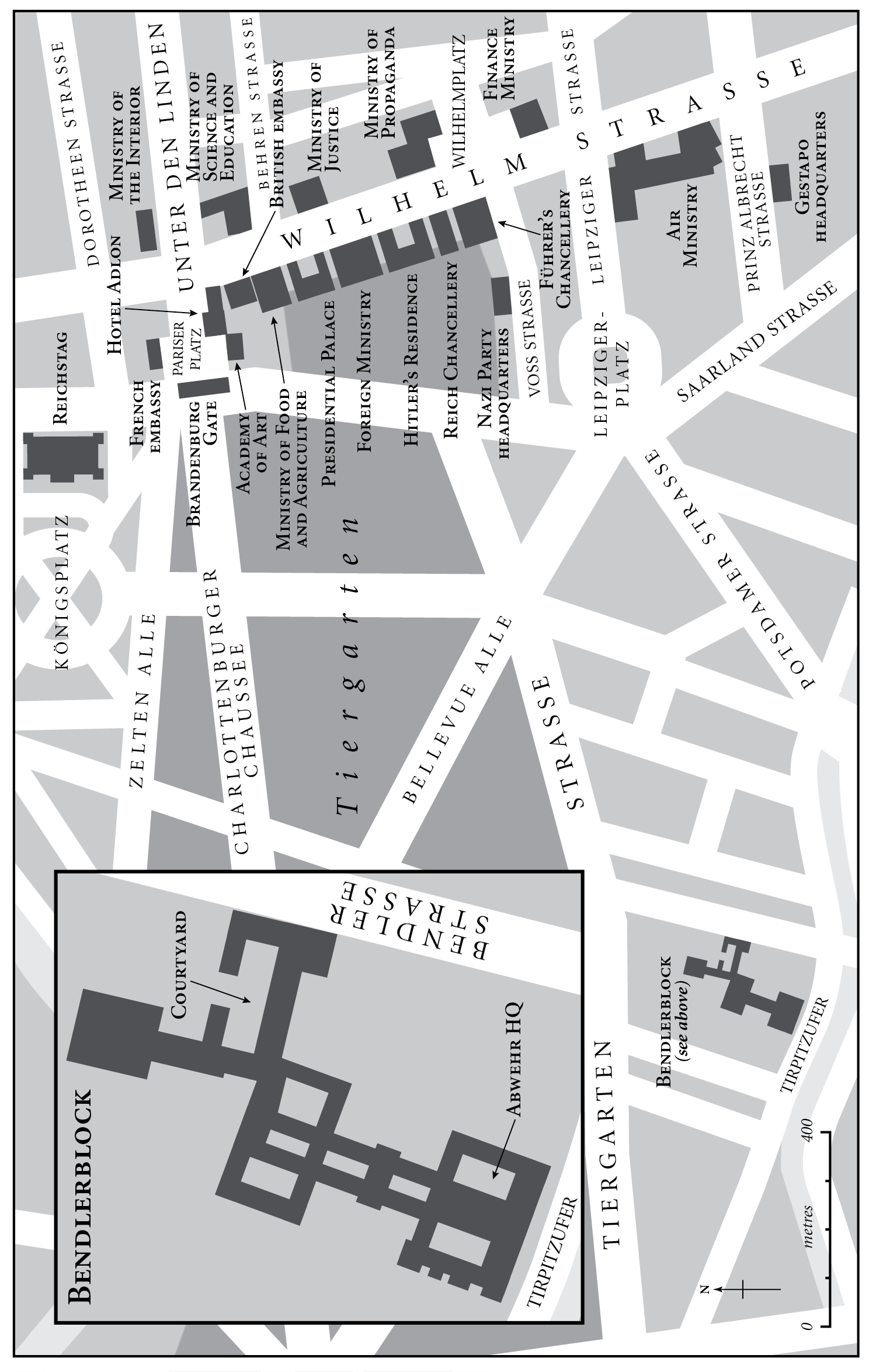

Map: Berlin’s administrative district

Map: Germany, 1944

Prologue

1 Carl Goerdeler

2 Ludwig Beck

3 Wilhelm Canaris

4 Madeleine and Paul

5 Germany in the Shadow of War

6 The Emissaries

7 ‘All Our Lovely Plans’

8 March Madness

9 The March to War

10 Switzerland

11 Halina

12 Sitzkrieg

13 Warnings and Premonitions

14 Felix and Sealion

15 The Red Three

16 Belgrade and Barbarossa

17 General Winter

18 The Great God of Prague

19 Rebound

20 Codes and Contacts

21 Of Spies and Spy Chiefs

22 Mistake, Misjudgement, Misfire

23 The Worm Turns

24 The End of Dora

25 Enter Stauffenberg

26 Valkyrie and Tehran

27 Disappointment, Disruption, Desperation

28 The Tip of the Spear

29 Thursday, 20 July 1944

30 Calvary

31 Epilogue

32 After Lives

Afterword: Cock-up or Conspiracy?

Reader’s Note

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Notes

Index

Also by Paddy Ashdown

About the Author

About the Publisher

Illustrations

Carl Goerdeler. (Papers of Arthur Primrose Young, Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick: MSS.242/X/GO/3)

Wilhelm Canaris. (Popperfoto/Getty Images)

Ludwig Beck. (Ullstein bild Dtl: Getty Images)

Henning von Tresckow. (Ullstein bild Dtl: Getty Images)

Hans Oster. (AfZ: NL Hans Bernd Gisevius/6.7)

Erwin von Lahousen. (ÖNB)

Hans Bernd Gisevius. (SZ Photo/Süddeutsche Zeitung)

Robert Vansittart. (Scherl/Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo)

Stewart Menzies and his wife Pamela. (Evening Standard/Stringer/Hulton Archive: Getty Images)

Neville Chamberlain on his return from Munich, September 1938. (Keystone/Stringer/Hulton Archive: Getty Images)

Paul Thümmel, Agent A54. (UtCon Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

Madeleine Bihet-Richou.

Ursula Hamburger (‘Sonja’).

Ursula with her children, Nina, Micha and Peter Beurton. (Courtesy of Michael Hamburger and Peter Beurton)

Leon ‘Len’ Beurton. (Courtesy of Peter Beurton)

Halina Szymańska. (Courtesy of Marysia Akehurst)

Alexander Foote. (CRIA/Jay Robert Nash Collection)

Rachel Duebendorfer. (The National Archives, ref. KV2/1619)

Allen Dulles. (NARA 306-PS-59-17740)

Rudolf Roessler. (CRIA/Jay Robert Nash Collection)

Sándor Radó with his Geopress staff.

Sándor and Helene Radó with their two sons, June 1941. (Bundesarchiv, Berlin-Lichterfelde)

‘De Favoriet’, the Jelineks’ shop in The Hague, c. 1939.

Bernhard Mayr von Baldegg, Alfred Rosenberg and Max Waibel.

The Wolfsschanze map room after Stauffenberg’s failed assassination attempt, 20 July 1944. (Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group: Getty Images)

Stauffenberg, Puttkamer, Bodenschatz, Hitler, Keitel, 15 July 1944. (Photo12/UIG via Getty Images)

Goerdeler on trial. (Keystone/Hulton Archive: Getty Images)

The Tirpitzufer, c.1939.

‘La Taupinière’, c. 1937.

Alexander Foote’s flat in Lausanne.

Halina Szymańska’s fake French passport.

Foote’s radio.

Station Maude, Olga and Edmond Hamel’s radio.

Halina Szymańska’s false passport. (Courtesy of Marysia Akehurst)

The Radó family’s apartment building at 113, rue de Lausanne in Geneva. (Bundesarchiv, Berlin-Lichterfelde)

The Hamels’ radio shop in the Geneva suburb of Carouge, c.1939. (Bundesarchiv, Berlin-Lichterfelde)

Epigraphs

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

From W.H. Auden, ‘September 1, 1939’

‘The only salvation for the honest man is the conviction that the wicked are prepared for any evil … It is worse than blindness to trust a man who has hell in his heart and chaos in his head. If nothing awaits you but disaster and suffering, at least make the choice that is noble and honourable and that will provide some consolation and comfort if things turn out poorly.’

Baron vom Stein, urging Friedrich Wilhelm III to oppose Napoleon in 1808

Introduction

This book is about those at the very top of Hitler’s Germany who tried to prevent the Second World War, made repeated attempts to kill him, did all they could to ensure his defeat, worked for an early peace with the Western Allies, and ultimately died terribly for their cause.

Most of my books have been about individual events, or people. The canvas of this one, by contrast, encompasses every sector of German society during the war; international statesmanship – or lack of it – in capitals from Berlin, to London, to Washington, to Moscow; battles fought from the shores of the Volga to the shadow of the Pyrenees; and spy rings plying their trade in Geneva, Zürich, Paris, Amsterdam, Istanbul and beyond.

Now that I have written it, I am a little surprised to find that a work I thought would tell the history of the Second World War through different eyes turns out also to be a story on the subject to which I return again and again: how human beings behave when we are faced with the challenges of war – and especially how, when confronted by great evil and personal jeopardy, we decide between submission and resistance: between loyalty and betrayal.

Is it ever possible to be both traitor and patriot? Is it treachery to betray your state if to do otherwise is to betray your humanity? Even if treachery changes nothing, must you still risk being a traitor in the face of great evil, if that is the only way to lighten the guilt that will fall on your children and your future countrymen? How do people make these choices? How do they behave after they have made them?

Dietrich Bonhoeffer – himself one of those murdered for his role in the anti-Hitler resistance – said: ‘Responsible action takes place in the sphere of relativity, completely shrouded in the twilight that the historical situation casts upon good and evil. It takes place in the midst of the countless perspectives from which every phenomenon is seen. Responsible action must decide not just between right and wrong, but between right and right and wrong and wrong.’

So it is, exactly, here. There are no blacks and whites, just choices between blacker blacks and whiter whites. There are no triumphal personal qualities, and no triumphant outcomes. Just flawed individuals who, at a time of what Bonhoeffer referred to as ‘moral twilight’, felt compelled to do the right thing as they saw it. That is a lesser triumph than we might wish for in dangerous times, but it was then – and is now – probably the only triumph we can reasonably expect.

This story is, at its heart, a tragedy. Like all great tragedies it involves personal flaws, the misjudgements of the mighty, and a malevolent fate. There is individual pity and suffering, and a deal of personal stupidity, here.

But – and herein lies the history – since these were human beings of consequence, their personal decisions affected lives and events far beyond their circle and their time.

The two central historical questions posed by this book are stark: did the Second World War have to happen? And if it did, did it have to end with a peace which enslaved Eastern Europe?

My purpose is not to provide definitive answers, but rather to present some facts which are not generally known – or at least not taken account of – and place these against the conventional view of the origins, progress and outcomes of World War II.

In reading this book you may be struck, as I was in writing it, by the similarities between what happened in the build-up to World War II and the age in which we now live. Then as now, nationalism and protectionism were on the rise, and democracies were seen to have failed; people hungered for the government of strong men; those who suffered most from the pain of economic collapse felt alienated and turned towards simplistic solutions and strident voices; public institutions, conventional politics and the old establishments were everywhere mistrusted and disbelieved; compromise was out of fashion; the centre collapsed in favour of the extremes; the normal order of things didn’t function; change – even revolution – was more appealing than the status quo, and ‘fake news’ built around the convincing untruth carried more weight in the public discourse than rational arguments and provable facts.

Painting a lie on the side of a bus and driving it around the country would have seemed perfectly normal in those days.

Nevertheless, I have found myself inspired in writing this story. It has proved to me that, even in such terrible times, there were some who were prepared to stand up against the age, even when their cause was hopeless, and even at the cost of their lives.

I hope that you will find that inspiration here, too.

Main Dramatis Personae

Anulow, Leonid Abramovitsch – Alias ‘Kolja’ – Soviet ‘Rezident’ in Switzerland before Radó

Attolico, Bernardo – Italian ambassador in Berlin

Bartik, Major Josef – Head of Czech intelligence 1938

Beck, General Ludwig – Chief of staff of the German army until dismissed by Hitler in 1938. The army leader of the anti-Hitler plot

Bell, George – Anglican theologian and bishop of Chichester

Beneš, Edvard – Czech president 1935–38

Beurton, Leon Charles – Known as Len. Friend of Alexander Foote. Radio operator Dora Ring

Bihet-Richou, Madeleine – Lover of Erwin Lahousen. French secret services

Blomberg, Field Marshal Werner von – Commander-in-chief of the German army until dismissed by Hitler in 1938

Bock, Field Marshal Fedor von – Von Tresckow’s uncle. Commander of Army Group Centre

Bolli, Margrit – Alias ‘Rosy’. Rote Drei radio operator

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich – Theologian, German pastor and key plotter

Bonhoeffer, Dr Karl – Father of Dietrich. Took part in the September 1938 plot

Bosch, Robert – German industrialist. Founder of the Bosch industrial empire. Supporter of Goerdeler

Brauchitsch, Field Marshal Walther von – Commander-in-chief of the German army up to the defeat at Moscow in 1941

Cadogan, Sir Alexander – Head of the British Foreign Office

Canaris, Erika – Wife of Wilhelm

Canaris, Wilhelm – Head of the German Abwehr until his dismissal in 1944

Chojnacki, Captain Sczcęsny – Polish intelligence spy-master based in Switzerland

Ciano, Galeazzo – Italian foreign minister

Colvin, Ian – Central European correspondent of the London News Chronicle. Arranged von Kleist-Schmenzin’s visit to Britain in 1938

Daladier, Édouard – French prime minister

Dansey, Sir Claude – Deputy head of MI6 and founder of the ‘Z Organisation’. Known as ‘Colonel Z’

Dohnányi, Hans von – Lawyer in the Abwehr and a key conspirator

Donovan, Major General William ‘Wild Bill’ – Head of the US intelligence agency (OSS)

Duebendorfer, Rachel – Alias ‘Sissy’. ‘Dora Ring’ agent

Dulles, Allen – OSS representative in Bern

Eden, Anthony – British foreign secretary

Farrell, Victor – MI6 head in Geneva

Fellgiebel, General Fritz Erich (known as Erich) – Chief of the German army’s Signal Establishment and a key plotter

Foote, Alexander – Alias ‘Jim’. Radio operator, ‘Dora Ring’

Franck, Aloïs – Paul Thümmel’s Czech spy-handler

François-Poncet, André – French ambassador in Berlin at the time of Munich

Fritsch, Colonel General Werner von – Commander-in-chief of the German army until his dismissal on trumped-up charges of homosexuality in January 1938

Gabčik, Josef – Operation Anthropoid Czech agent

Gersdorff, Rudolf-Christoph von – Henning von Tresckow’s staff officer; volunteered to assassinate Hitler by suicide bombing on 21 March 1943

Gibson, Colonel Harold ‘Gibby’ – Head of the MI6 station in Prague

Gisevius, Hans Bernd – The ‘eternal plotter’ in the Abwehr. Key early conspirator and Canaris’s conduit to Halina Szymańska

Goerdeler, Anneliese – Carl Goerdeler’s wife

Goerdeler, Carl – Key early plotter. Ex-mayor of Leipzig

Groscurth, Lieutenant Colonel Helmuth – Canaris’s liaison officer with the army at Zossen

Guisan, General André – Head of the Swiss army

Haeften, Lieutenant Werner von – Von Stauffenberg’s adjutant

Halder, Colonel General Franz – German chief of staff under von Brauchitsch

Halifax, Lord Edward – British foreign secretary under Chamberlain and a key appeaser

Hamburger, Ursula – Née Kuczynski. Code name ‘Sonja’. Soviet spy who arrived in Switzerland in 1936

Hamel, Olga and Edmond – ‘Dora Ring’ radio operators

Hassell, Ulrich von – German ambassador in Italy before the war. Liaison between Beck and Goerdeler

Hausamann, Captain Hans – Founder of the Büro Ha, a private intelligence bureau in Switzerland

Heinz, Lieutenant-Colonel Friedrich – Leader of the commando who were to kill Hitler in 1938

Henderson, Sir Nevile – British ambassador in Berlin before 1939

Hoare, Sir Samuel, MP – One of Chamberlain’s leading appeasement supporters

Hohenlohe von Langenberg, Prince Maximilian Egon – Freelance spy. Friend of Dulles, Canaris and Himmler

Jelinek, Charles and Antoinette – Owners of ‘De Favoriet’ bric-à-brac shop in The Hague

Keitel, Field Marshal Wilhelm – Chief of the German armed forces high command

Kleist-Schmenzin, Ewald von – German emissary of the opposition to Hitler; saw Churchill in London in August 1938

Kluge, Field Marshal Günther von – Commander of Army Group Centre. Reluctant plotter

Kordt, Erich – Head of Ribbentrop’s office in Berlin

Kordt, Theo – Brother of Erich. Official at the German embassy in London

Kubiš, Jan – Operation Anthropoid Czech agent

Lahousen, Major General Erwin von – Head of the Austrian Abwehr and then senior officer in the German Abwehr. Close to Canaris and a key plotter. Lover of Madeleine Bihet-Richou

Manstein, Field Marshal Erich von – Commander of Army Group South and mastermind of the Kursk offensive

March, Juan – Mallorcan businessman and prime mover in Spain – contact of Canaris and MI6

Masson, Roger – Head of Swiss intelligence

Mayr von Baldegg, Captain Bernhard – Staff member of Swiss army intelligence; Waibel’s deputy head

Menzies, Sir Stewart – Head of MI6

Mertz von Quirnheim, Colonel Albrecht – Friend of Stauffenberg; involved in the 20 July 1944 plot

Moltke, Count Helmuth von – Founder of the ‘Kreisau Circle’

Morávec, Colonel František – Head of the Czech intelligence service

Morávek, Václav – Resistance leader in Prague

Mueller, Josef – Canaris’s spy in the Vatican

Navarre, Henri – Madeleine Bihet-Richou’s French intelligence ‘handler’

Niemöller, Martin – Anti-Hitler Lutheran pastor

Olbricht, General Friedrich – Key plotter. Involved in the 20 July coup

Oster, Colonel Hans – ‘Managing director’ of the attempted 1938 coup. Head of Z Section in the Tirpitzufer

Pannwitz, Heinz – SD officer in charge of finding the ‘Dora Ring’

Payne Best, Captain Sigismund – MI6 officer captured at Venlo

Puenter, Dr Otto – ‘Dora’ agent – also in touch with MI6

Radó, Sándor – Head of the ‘Dora’ spy network

Ribbentrop, Joachim von – German ambassador to London and later Hitler’s foreign minister

Rivet, Colonel Louis – Head of French military intelligence (SR)

Roessler, Rudolf – Codename ‘Lucy’. Private purveyor of intelligence in Switzerland

Sas, Gijsbertus Jacobus – Dutch military attaché in Berlin; contact of Oster and Waibel

Schacht, Hjalmar – German minister of economics and president of the Reichsbank

Schellenberg, Walter – Heydrich’s protégé and mastermind of Venlo

Schlabrendorff, Fabian von – German lawyer. Liaison between Tresckow in Russia and Beck in Berlin

Schneider, Christian – Alias ‘Taylor’. Swiss businessman. Cut-out supplying information from Roessler to the Dora Ring

Schulenburg, Friedrich-Werner von der – Pre-war ambassador to Moscow and senior resistant

Schulte, Edouard – German businessman and one of Chojnacki’s agents

Sedláček, Karel – Alias ‘Charles Simpson’. Czech intelligence officer in Bern

Stauffenberg, Colonel Claus Schenk, Graf von – Architect and perpetrator of the 20 July 1944 bomb plot

Stevens, Major Richard – MI6 officer captured at Venlo

Suñer, Serrano – Spanish foreign minister

Szymańska, Halina – Wife of the Polish military attaché in Berlin before the war. Channel for Canaris to pass information to Menzies

Thümmel, Paul – Many aliases. MI6 agent A54. Important spy in the early part of the war

Timoshenko, Marshal Semyon – Commander of Soviet forces at Moscow, Stalingrad and Kursk

Tresckow, Henning von – Chief of staff of Army Group Centre; a key plotter

Trott zu Solz, Adam von – German lawyer, diplomat and active resister

Vanden Heuvel, Count Frederick – Head of MI6 in Bern after 1941

Vansittart, Sir Robert – Head of the pre-war British Foreign Office

Waibel, Captain Max – Swiss intelligence officer

Weizsäcker, Ernst von – Head of the German Foreign Office and key plotter

Wilson, Sir Horace – Personal adviser to Chamberlain. Appeasement supporter

Witzleben, General Erwin von – Commander of the Berlin garrison and de facto leader of the September 1938 coup

Young, A.P. – One of Vansittart’s ‘spies’ in contact with Goerdeler

Zaharoff, Basil – Director of Vickers and notorious arms dealer

Prologue

To the millions whose votes helped make Adolf Hitler chancellor of Germany, he was the hero who would rescue them from the humiliations of the Versailles Treaty and the shaming chaos that followed.

John Maynard Keynes, who attended the 1919 peace conference, condemned Versailles afterwards in unforgiving and uncannily prophetic terms: ‘If we aim at the impoverishment of Central Europe, vengeance, I dare say, will not limp. Nothing can then delay for very long the forces of Reaction and the despairing convulsions of Revolution, before which the horrors of the late German war will fade into nothing, and which will destroy, whoever is victor, the civilisation and the progress of our generation.’

Keynes was not the only person to understand that in the punitive conditions imposed by Versailles lay the seeds of another explosion of German militarism. Others referred to it as ‘the peace built on quicksand’.

Under Clause 231 of the Treaty, the ‘War Guilt’ clause, Germany was deprived of all her colonies, 80 per cent of her pre-war fleet, almost half her iron production, 16 per cent of coal output, 13 per cent of her territory (including the great German-speaking port of Danzig) and more than a tenth of her population. To add to these humiliations, the victorious Allies also planted a deadly economic time bomb beneath what was left of the German economy. This took the form of war reparations amounting to some $US32 billion, to be paid largely in shipments of coal and steel.

In 1922, when Germany inevitably defaulted, French and Belgian troops occupied the centre of German coal and steel production in the Ruhr valley. Faced with the collapse of the domestic economy, the German government sought refuge in printing money, with the inevitable consequence of explosive runaway inflation. In 1921 a US dollar was worth 75 German marks. Two years later, each dollar was valued at 4.2 trillion marks. By November 1923, a life’s savings of 100,000 marks would barely buy a loaf of bread.

In the months immediately following the Armistice, an armed uprising inspired by Lenin and the Russian Revolution ended in 1919 with the removal of the kaiser and elections for Germany’s first democratic government, christened the Weimar Republic after the city in which its first Assembly took place. It all began in a blaze of hope, but soon descended into squabbling and dysfunctionality. Unstable, riven with shifting coalitions, burdened with war reparations, incapable of meeting the challenges of the global depression, the new government, along with politicians of every stripe and hue, soon became objects of derision and even hatred. Compromise was seen as failure, easy slogans replaced rational policies, the elite were regarded with suspicion, and the establishment was deluged with accusations of corruption and profiteering.