Полная версия

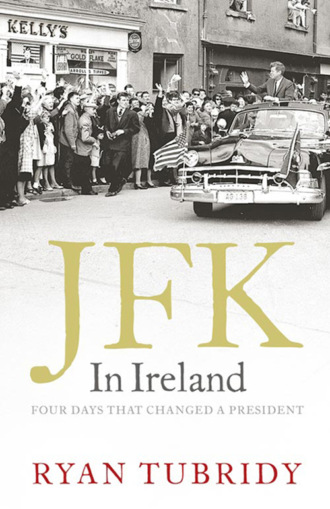

JFK in Ireland: Four Days that Changed a President

JFK

In Ireland

FOUR DAYS THAT CHANGED A PRESIDENT

RYAN TUBRIDY

For Ella and Julia My little dotes

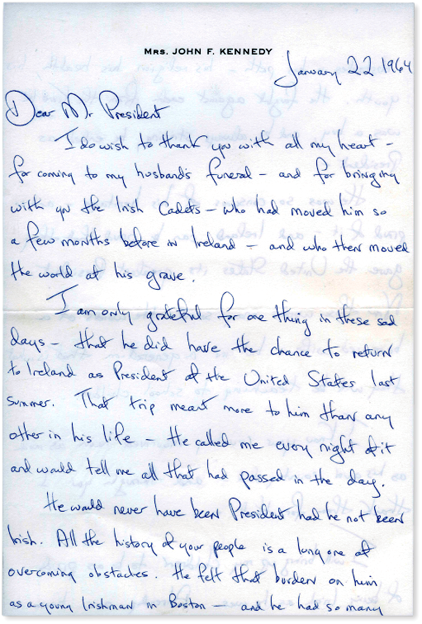

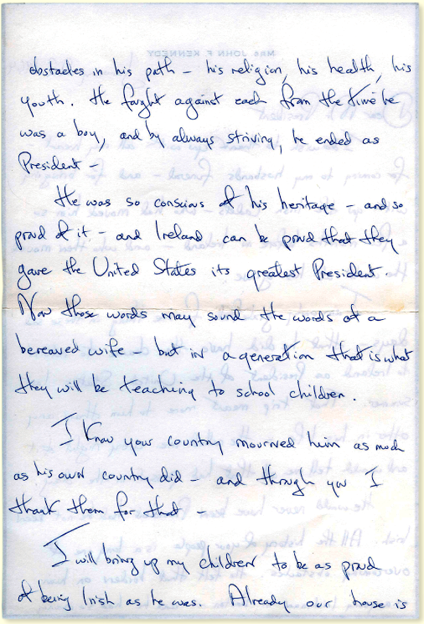

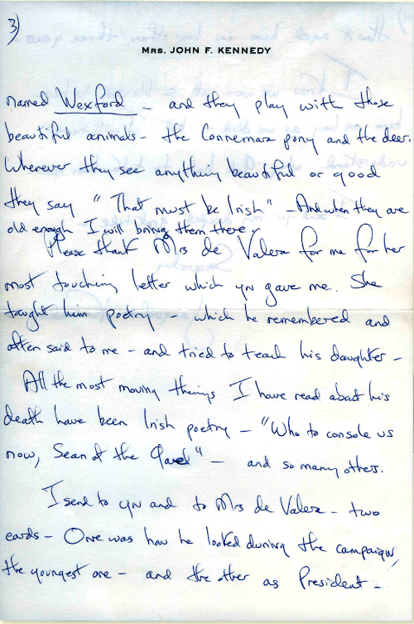

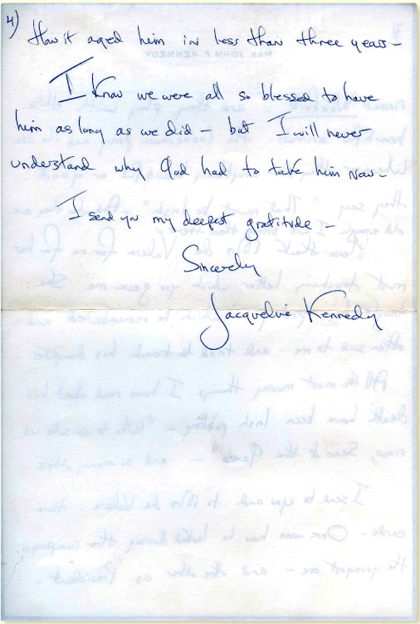

A letter from Jacqueline Kennedy to President de Valera, thanking him for attending her husband’s funeral.

The Irish tricolour comes alive for JFK as children from local schools dressed in orange, white and green rainwear rush to greet him in Galway.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE The Kennedys: From Poverty to Power

CHAPTER TWO The Kennedys Come Home, 1930s–1950s

CHAPTER THREE Wooing the President

CHAPTER FOUR Planning the Visit

CHAPTER FIVE The European Tour Begins

CHAPTER SIX Arriving in Dublin

CHAPTER SEVEN New Ross

CHAPTER EIGHT Dunganstown

CHAPTER NINE Wexford Harbour

CHAPTER TEN The Garden Party

CHAPTER ELEVEN Iveagh House

CHAPTER TWELVE Cork

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Arbour Hill

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Leinster House

CHAPTER FIFTEEN Dublin Castle

CHAPTER SIXTEEN The Last Supper

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Galway

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN Limerick

CHAPTER NINETEEN Shannon Airport

CHAPTER TWENTY The Road to Dallas

CHAPTER TWENTY–ONE JFK in Ireland: The Legacy

NOTES

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PICTURE CREDITS

Copyright

About the Publisher

Badge of honour: three small children cheer JFK during his Irish visit.

PROLOGUE

Kenny O’Donnell, the President’s right–hand man was flabbergasted. “Ireland?” he said. “Mr. President, may I say something? There’s no reason for you to go to Ireland. It would be a waste of time. You’ve got all the Irish votes in this country that you’ll ever get. If you go to Ireland, people will say it’s just a pleasure trip.”

Nobody thought it was a good idea. Not the American media, not the presidential advisers, nobody. But President Kennedy had made up his mind and when O’Donnell went back to the President the following day to relay this message, Kennedy looked up at him from his newspaper “with an air of exasperated impatience”. “Kenny, let me remind you of something,” he said with a distinct air of finality and authority. “I am the President of the United States, not you. When I say I want to go to Ireland, it means that I’m going to Ireland. Make the arrangements.”1

It was meant to be a band–aid trip to key European allies, an attempt to show them that America cared as the Soviet beast breathed down their necks. Italy demanded a visit, Germany needed attention, England desired a distraction and France sulked. But there were bigger problems at play; Italy was between governments and there was an ailing Pope in the Vatican. In Germany, Chancellor Adenauer’s government was in disarray after the Der Spiegel affair. In England, Harold Macmillan was suffering through the extraordinary Profumo Affair, which saw his War Minister caught lying about his affair with a call–girl who happened to be sharing a bed with Russian naval attaché Eugene Ivanov. The thought of America’s glamorous young president popping over for tea was political manna for the electorally beleagured leaders of Europe.

June 1963 was as busy a month as any for President Kennedy. He had some significant dates in his diary and he had some housekeeping to attend to. In the latter category fell his appointment with Governor John Connolly of Texas. The two men needed to discuss the President’s visit to Dallas some five months later. In the former category, Kennedy delivered his “Peace Speech’ in which he addressed nuclear weapons and atmospheric test bans and urged the world to “cherish our children’s future”. But there were domestic problems too as the Kennedy administration confronted one of the great seismic struggles of twentieth century American politics, that of civil rights.

At home, the media natives were getting restless; the Washington Post made the wry observation that “Ireland is the only country the President will visit that has what can be described as a firmly–established and durable Government” while in a reference to the race riots in the South, Senator Hugh Scott said “I’d rather see him go to Birmingham (Alabama) than Berlin just now”.2 The spring of 1963 saw Birmingham inflamed with racial tension as the civil rights movement, spearheaded by Dr Martin Luther King Jr, sought to overthrow the bastions of racial segregation.

“It would be difficult to dream up a more unjustified and time-wasting trip than the one on which President Kennedy is scheduled to embark”, trumpeted an indignant New York Herald, before adding, “In Rome Mr. Kennedy will find neither a Pope nor an established Government; in London he will find a Prime Minister with other things on his mind. In Germany, too, he will find something in the nature of a ‘lame duck’ Government.” This grave assessment of the international situation was capped by a side–swipe at the other “explanation of the trip – the sentimental call of Dublin and the Kennedy ancestral town of New Ross; but surely his Irish friends would understand that urgent Congressional and racial problems required his continued presence in Washington at the moment.”3

And yet, the man who was always interested in history and global politics, the man who started life as a journalist and had visited Europe on the cusp and in the aftermath of World War II, wanted to go to. He not only wanted to go, he felt entitled to a little something for himself. John Fitzgerald Kennedy wanted to visit the land of his forebears. He wanted to go home.

CHAPTER ONE The Kennedys: From Poverty to Power

Ireland in the 1840s was a country on its knees. It was a time that robbed a nation of a generation. The exodus that took place saw the kernel of the Kennedy clan take hold on the shores of Boston. Here was a family forced together by the horrors of history. John F. Kennedy’s great–grandparents fled the greatest disaster that this island ever witnessed – The Great Famine. Caused by the blight of the potato crop in 1845, this killed a million Irish men, women and children in the course of five years, an eighth of the island’s total population, while another million fled the plights of starvation and disease.

It is hard to put this catastrophe into context as there is a distinct lack of contemporary reference, or indeed deference, to this tragic episode. Yet it was our Holocaust, it was the wind that sent our people like feathers from a pillow to all corners of the globe and particularly to Britain, Australia and the relatively youthful USA. Boston especially was a natural fit for the Irish. Like an exaggerated Dublin, the leafy city was as near to Ireland as a homesick peasant was going to get.

Among those who fled was John F. Kennedy’s great–grandfather Patrick Kennedy, who left New Ross, County Wexford, in 1848 for Liverpool from where he sailed to Boston. The fact that the third son of a Wexford farmer managed to cobble together enough money to pay for his voyage was an achievement in itself. While most of those on board that boat to Boston were fleeing poverty and almost certain death, Patrick saw his move to America as a search for something better. Like so many others of his generation, he would never see his parents or his brother and sister again.4

Either during the voyage or more probably when he arrived in Boston, Patrick met a fellow Wexford woman, Bridget Murphy.The two married in Boston, had four children and Patrick supported the family through his work as a cooper, making barrels and casks. It was in Boston that four families – the Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys, the Murphys and the Coxs – would mix, work and intermarry. It was here too that the upwardly mobile next generation would endeavour to shed their links with the old country. To this second generation, Ireland would represent a past without promise, a land of impoverished indignity and political impotence.

The Land of Opportunity was a harsh one for immigrants of all nationalities, but the Irish were on the lower rungs of society in 19th–century America and the attitude to them was ugly. Job adverts frequently read “No Irish need apply” and they could only find accommodation in ghettos, nicknamed “Paddyville” or “Mick Alley”, despite the fact that by 1850, a third of the population of Boston was Irish. They were seen as filthy, hard–drinking Catholics, under the thumb of the Pope. They also spoke in an accent no one could understand but their own people. Most Irishmen found work as manual labourers, and the paltry salaries meant they had to live in slum conditions. The only way to survive was to work long, back–breaking hours, and although the shops stocked plenty of food, unlike those back in Ireland, the Irish couldn’t afford to buy much of it. Like many of his fellow immigrants, Patrick Kennedy died prematurely after just ten years of this new life.

Alone, with four children to raise, Bridget embodied what would become the Kennedy work ethic. She worked as a shop assistant, took in lodgers and cleaned houses. When she had saved up enough money, Bridget bought the shop she worked in, expanded the business and started selling groceries and alcohol. She was going to raise her family’s standard of living through sheer determination and grit, even if it killed her, as it had her husband.

Patrick Joseph Kennedy (John F. Kennedy’s grandfather) was just one year old when his father died. Given that three in ten children living in American cities perished before the age of one in the mid–19th century, and the fatherless were more vulnerable than most, it was a miracle that he survived at all. Known to all as PJ, he left school at fourteen and worked on the Boston docks. Like his mother, he was a good saver and with some financial help from Bridget, PJ bought his own saloon in East Boston. By the time he hit thirty, PJ owned three such saloons and ran a side business importing whiskey.

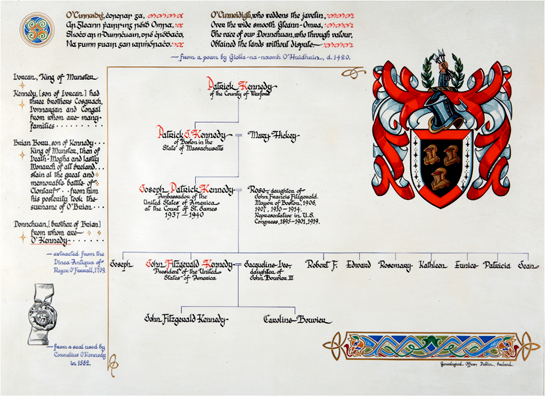

The Kennedy coat of arms and family tree. Down the left side are the names of Kennedy ancestors, beginning with Lorcan, King of Munster. At the top of the chart is an excerpt of a poem by Giolla that dates back to 1420.

Patrick J. Kennedy, paternal grandfather of JFK.

Around Boston, PJ Kennedy was seen as a fixer, somebody who could get things done, a good guy who was always ready to do a favour for you. He dispensed advice across the bar in his saloons, helping men to find jobs and mothers to get medical help for sick babies. He had an ability to listen, as well as an eloquence that won him friends wherever he went, so when he decided to run for public office in 1884, he had plenty of people willing to vote for him. He was a perfect fit for the offices he was about to win, first in the Massachusetts State Legislature and later in the State Senate. The brief generational journey from a devastated port in Wexford to the state political ladder was not typical – not unless you were a Kennedy – but he was setting a pattern for the generations to come.

With his professional and political situation in hand, PJ turned to the personal, and for this he set his sights on Mary Augusta Hickey. Always aiming slightly above his station, PJ didn’t mind that Mary was from a “better” Irish–American family, wealthier than his own; he knew his mind. Opportunities for social advancement were limited in the notoriously snobbish world of Boston high society, particularly if you had Irish Catholic heritage, and Mary knew it. This was a society that was as anglicised as it was rarefied. The rulers of this pompous roost were the Boston Protestant élite – the so–called Boston Brahmins, made up of a select number of Boston families who celebrated each other at parties, in politics and in toasts:

And this is good old Boston,

The home of the bean and the cod,

Where the Lowells talk only to Cabots,

and the Cabots talk only to God.

Yet Mary Augusta Hickey was won over by PJ’s affability and ambition and in 1887 she duly became Mrs Mary Kennedy, then gave birth to a son on 6 September, 1888. Rather than calling her first–born after his father, as was the norm, the class–conscious Mrs Kennedy christened the boy Joseph Patrick, and as he grew older, his mother always introduced him as Joseph.5 His friends would call him Joe. The Irish name Patrick was a scar from an unwanted past that she preferred to remove.

Over the next decade, life improved for many Irish–Americans and none more so than for Mary and PJ. In 1901, the respectable couple sent young Joe to Boston Latin, a Protestant secondary school that boasted such alumni as Benjamin Franklin. Joe stood out from the start. Despite being one of a handful of Catholics in a Protestant school, the boy thrived and was so popular among his classmates that he was elected class president. He did well enough at school to be accepted as a student at Harvard University, where he played on the baseball team.

Harvard boasted a number of college clubs, which granted privileged access to the Old Boys’ Network and should have given Joe a headstart in one of the big brokerage firms in Boston. However, despite his popularity and his many achievements at Harvard, to the well–groomed Wasps of Ivy League colleges, Joe was still a ‘Mick’. He had two strikes against him: he was too Catholic and his family’s money was too new, so he found himself blackballed from the most influential clubs. Kennedy would never forget this rejection.

History had different plans for Joseph Patrick Kennedy and all who would follow him. Left to blaze his own trail, Joe got a job as a bank examiner and in 1913, he made his first big deal when he borrowed enough money to take control of the Columbia Trust Company, the Boston–Irish bank his own father had helped to set up in 1892, while it was being threatened with takeover.6 He had a genuine gift for business and over the next few years would make a fortune speculating on the stock market.

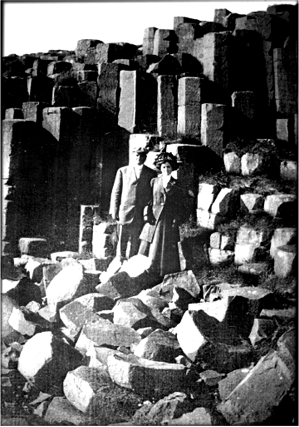

John F. Fitzgerald, JFK’s maternal grandfather, and Rose, JFK’s mother, at the Giant’s Causeway in 1908.

The Fitzgerald connection

Just two years out of Harvard, Joe repeated family history by setting his sights above his social station and falling in love with Rose Fitzgerald, a member of one of the Boston Irish community’s first families. Descended from Thomas Fitzgerald, who had left Ireland in 1854, the Fitzgerald family had fared better than the Kennedys.

Rose’s father, John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, was one of Boston’s most colourful and mercurial characters. Though he studied at Harvard medical school, he only lasted two years there because he had one real passion, and that was politics. He knew that money couldn’t buy you social acceptability in the snobbish world of Boston high society, but political office was bound to help. Honey Fitz was the consummate Irish–American politican; a back–slapping wheeler–dealer with the gift of the gab. He became a Congressman in 1895 and then, most famously, Mayor of Boston from 1905–07 and 1910–12, the first Irish–American to be voted into that post.

As a teenager Rose Fitzgerald acted as hostess at many of her father’s political functions. In 1906, Joe Kennedy began to pursue her, although Honey Fitz didn’t warm to the young Kennedy. He was determined to protect his first–born daughter from this brash young man and did his utmost to keep the couple apart. In fact, he managed it for eight years, but Honey Fitz didn’t count on Joe’s sheer determination and while he was preoccupied by a low point in his political career in 1914, Kennedy struck and the two were married.

The modern epic that constitutes the Kennedy story begins here. In 1915 Joseph Jr was born, and Honey Fitz told anyone who would listen that his grandson would be president in the White House one day. In 1917 John Fitzgerald Kennedy came into the world, and in the ensuing years Rose would give birth another seven times.

Displaying a competitiveness that would prove somewhat genetic, Joseph Kennedy excelled in anything he applied himself to and found his niche talent was in the world of business. By the 1920s, Kennedy had made a fortune speculating on the stock market. His money was useful in a modern sense but his success wasn’t enough to impress the Boston Brahmins, whose only currency was class. Attempts to join country clubs in Boston were rebuffed. His father was still referred to by the Brahmins as “Pat the tavern keeper”7. Almost eighty years after his grandfather set foot on Boston harbour, the Irish were still being treated as second–class citizens and Joe Kennedy was fed up with it. He decided to start afresh in New York, where he moved his burgeoning family in 1927, claiming that Boston “was no place to bring up Catholic children”. Joe and Rose now divided their time between New York, Hyannis Port on Cape Cod, Palm Beach, Florida, and Boston. Joe became wealthier with every decade, bringing his ruthless and relentless energy to the stock exchange, to Hollywood, where he produced several hit films and helped to found the RKO studio, and to the liquor business, importing alcohol to the US both during Prohibition and after its repeal.

Joe and Rose were deeply ambitious for their children. They ached for them to excel, to win prizes, to be accepted, but the prejudice that had started at the Boston docks had travelled to the élite New York schools and not much had changed in this regard by the time Joe Jr and John F. Kennedy were of school age. As one contemporary commented, “To be an Irish Catholic was to be a real, real stigma – and when the other boys got mad at the Kennedys, they would resort to calling them Irish or Catholic.”8 Insults are part of the rough and tumble of boyhood shenanigans but it was more serious when the future president was refused access to certain schools favoured by the Brahmins. He was finally accepted by Choate, an exclusive boarding school in Connecticut, but found himself banned from joining many of the school’s prestigious clubs.

Young John Kennedy, nicknamed Jack by his family and close friends, was an average student who was fascinated by history and English, but not remotely so by mathematics or the sciences. Regularly unwell with a spastic colon, he lived his school and college days in the shadow of his irrespressible brother Joe, who was awarded the Harvard Trophy, a prize given to those who achieved both the best sporting and academic records. Jack wasn’t overly exercised by his brother’s achievements and made his way through Choate and then Harvard at his own pace, making lifelong friends, despite the occasional bout of racial prejudice. He was smartly groomed and well–spoken, but his sandy hair and blunt features gave him away as Irish before his surname was even mentioned, and the older, more puritanical Bostonian families still saw the Kennedys as nouveaux–riches upstarts.

As Joe Sr’s stock rose (metaphorically and otherwise), newspaper and magazine articles were written about his film and business interests, but time and time again they referred to the Kennedys as “Irish”, which was tiresome for both Rose and Joe Sr. On seeing the term used in a newpaper one morning, Joe is reported to have looked up and fumed “Goddam it! I was born in this country. My children were born in this country. What the hell does someone have to do to become an American?”9

Another family might have crumbled under such resentment and latent racism but it wasn’t the house style for the Kennedys, who soldiered on. Realising that money per se was not enough to win society’s acceptance, Joe Kennedy Sr pursued his career in politics, where respectability was attainable and money was always welcome. He pumped a fortune into Franklin D. Roosevelt’s successful presidential campaign of 1932 and for this, he was rewarded with the post of first Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, which Roosevelt established in 1934. For the 1936 campaign, Kennedy added to the small fortune he contributed by self–publishing a book entitled I’m for Roosevelt. All of this support was duly acknowledged and in 1937, as the world rumbled towards war, Joseph Patrick Kennedy, grandson of an immigrant cooper, was made American ambassador to the Court of St James. Kennedy was FDR’s man in Britain. In the space of a generation a tragic Irish family was slowly embodying the American Dream. The journey from Famine to Boston and now, the heart of the British diplomatic establishment was very quick but it was also vintage Kennedy.

A model of Irish Catholic achievement in America: a family portrait of the prosperous Kennedys, taken in 1938.

The ambassadorship was an exceptionally prestigious diplomatic position but in reality such posts are in the gift of the President and, to this day, they are often given to party grandees and important donors to party political funds. This appointment would prove to be a turning point in the story of the Kennedys and Ireland, as it was a year later, in 1938, that the head of the Kennedy clan met the Irish Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera. From here on, Irish–American relations would be transformed and all roads would lead to O’Connell Street, June 1963.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.