Полная версия

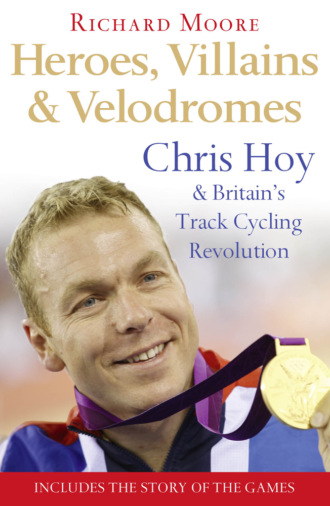

Heroes, Villains and Velodromes: Chris Hoy and Britain’s Track Cycling Revolution

‘We have kit we’ve been using in training but we haven’t used it here,’ confirms Boardman. ‘We produced some really sexy handlebars for the sprinters last year, but at last year’s world championships the Germans came along and took some pictures of our handlebars, and now they’ve got them.’ It is easy to see how this could happen. At a track meeting, where the teams occupy their pens in the centre, separated from each other only by metal fencing, equipment is easily visible. All kinds of people are sniffing around. And some, says Boardman, are spies. ‘If you leave stuff lying around the track centre,’ he points out, ‘then people will see it.’ It is fairly important, then, to keep the top Secret Squirrel ‘stuff’ hidden – and note, incidentally, the deliberately frivolous, almost Orwellian sounding, moniker assigned to Boardman’s ‘club’. ‘We’re paying a lot of money to develop this stuff,’ he points out, ‘so next year we’ll use it in competition, but it’ll be too late for anybody to copy.

‘And a lot of it you won’t even be able to see,’ he adds, looking satisfied. As well he might. He knows that, if nothing else, such talk will score points in the psychological war. Consider this: if it is frustrating for the opposition to look enviously at the state-of-the-art machines belonging to their rivals, then how frustrating must it be to know that you can’t even see half of what makes it state-of-the-art? It is the sporting equivalent of Donald Rumsfeld’s infamous ‘known unknowns’ argument. ‘There are known knowns,’ said the then US secretary of state for defense, speaking of the War on Terror. ‘Then there are known unknowns. But there are also unknown unknowns.’ Some of the stuff in Boardman’s Secret Squirrel Club comes into this category. As far as the opposition is concerned, it is an unknown unknown. How much of a mind-fuck is that?

This, mind you, is a game that goes on between all the teams, with psychological warfare a big part of track cycling for all kinds of reasons – the riders rub shoulders in the track centre, they warm up in full view of each other, the racing itself is gladiatorial; there are no hiding places; image and appearance is (almost) everything. Boardman doesn’t criticize other teams for ‘sniffing around.’ Far from it.

‘Oh, we do it,’ he says. ‘I don’t do it myself, because that would be too obvious. I have somebody doing it for me, and I can assure you they’re not wearing a GB T-shirt. I heard about one bike manufacturer sending guys who looked like cycling groupies in long hair and long shorts. They’d look daft and ask stupid questions and the mechanics would just stand there and tell them everything.’ Boardman shakes his head. ‘You have to be clever.’

What is remarkable about all of this – the confidence, the gold medals, the ample resources, the subterfuge, the aura of invincibility, the sheer ebullience – is that this is a British team we’re talking about. A British cycling team. Ten years ago British cycling teams were the designated whipping boys, and girls: that was their role. To other nations it must have seemed their raison d’etre. Yet now it is they who do the whipping, kicking the collective arse of the once dominant Australians. The Australians!

To fully understand how far the British track cycling team has come you must first understand where it was. It was nowhere. Over the decades there have been exceptions – outstanding individuals such as Reg Harris, Beryl Burton, Hugh Porter, Graeme Obree and indeed Boardman himself – but each succeeded despite the system, not because of it. Because there was no system.

In 1997, when Hoy began to be a regular member of the British team, he was given a racing outfit, ‘told to feel grateful for it’, and lent a bike, ‘a state-of-the-art bike – from the 1960s’, and told to feel grateful for that, too. In 1996, when he was selected for his first international event – the European Under-23 championships in Moscow – he was one of three riders, with no support staff. They could only afford to send three people, so they decided not to bother with a mechanic or a team manager. Compare and contrast that to the twenty-eight support staff in Palma.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of what has happened over the last decade – the development of a system every bit as efficient and effective as the old East German system, without the systematic doping – is that it just seems so unBritish. We don’t really do success – or not systematic success, at any rate. According to the December 2007 issue of the Observer Sports Monthly magazine, we are, in fact, ‘ritually accustomed to defeat’. According to Simon Barnes of The Times, we ‘have no contingency plan for excellence, no strategy for dealing with the calamity of victory’. When we win, we go off the rails. Whatever it takes to build on success, or even sustain it, we just don’t seem to possess it.

That Observer article (entitled ‘Born to Lose’) concluded by claiming that is not that we do not want to win: ‘We want to win as much if not more than anyone else. We just do not want to do what is necessary to win.’ We do not want to do what is necessary to win. Which raises the question: what is necessary to win? Well, if anyone knows the answer to this question it is Chris Hoy. And the British cycling team. How has this happened? And why in track cycling?

What struck me in Palma, as the British team dominated event after event, and my old – ahem – team-mate Chris Hoy confirmed himself as one of the all-time greats, was the realization that there was something – beyond winning – that was very special, and very unusual, about this team. There was planning, and attention to detail, and athletic talent – all these things, of course. But there was something else – a unique and very potent chemistry. And there were secrets – intriguing, closely-guarded secrets, from Boardman’s Secret Squirrel Club to the team’s employment of a clinical psychiatrist – someone whose previous work had been with inmates of a high-security hospital, but who, in 2002, had made the surprise career switch to work with Britain’s top cyclists. The success of his work with certain members of the team prompts Brailsford to say that he is ‘the best person I’ve hired – and I’ve hired some great people’.

Sporting success, skulduggery, psychiatry, suspicions of systematic doping, in a world of heroes, villains and velodromes … there could be a hell of a story here, I thought.

A couple of weeks after Palma, a month before he was to travel to Bolivia to try and set a new world kilometre record, I sat down with Hoy in a bar in Edinburgh and gave him my spiel: ‘I’d like to write a book – about you, and about this incredible year you have in front of you, taking in Bolivia, the World Cups, the crazy keirin circuit in Japan, the madness of six-day racing, the world championships in Manchester … and looking ahead to Beijing. Only, it won’t really be about you, as such, well it will, and it won’t – it’ll be part your story, your BMX-ing as a kid, that sort of thing, but it’ll also be the story of the British team – the revolution there’s been over the last ten years. I mean, it’s an incredible story, really, when you think about it … what do you think?

‘Okay,’ said Hoy.

PART 1

Portrait of the Athlete as a Young Man

CHAPTER 1

BMX Bandits

Ile de Ré, France, August 1992

Though he wasn’t to know it at the time, a seminal moment in Chris Hoy’s career occurred while he was on a family holiday on Ile de Ré, La Rochelle, western France, in August 1992. He was sixteen. And he had hired a bike for the holiday – a mountain bike.

At the same time, several hundred miles south of Ile de Ré, in the Spanish city of Barcelona, the Olympics were taking place, and a remarkable thing was happening there. It was remarkable if you were British, and a cyclist. Because a British cyclist by the name of Chris Boardman had reached the final of the men’s pursuit, and appeared to be on the verge of winning Britain’s first cycling gold medal in eighty-four years, when the quartet of Leonard Meredith, Ernest Payne, Charles Kingsbury and Benjamin Jones were victorious in the 1,810.5 metre team pursuit at the 1908 London Olympics. Boardman’s breakthrough was like Eddie the Eagle winning the ski jump – or seemed like it to many people.

And the British media responded accordingly – which is to say that, rather than focus on the athletic achievement, or any physical talent that Boardman may have possessed, they discovered a quirky angle: the fact that Boardman was riding a space-age Lotus bike, promptly christened ‘Superbike’. Superman, meanwhile, was all but ignored.

Boardman says now that he didn’t mind – that in fact it worked in his favour. ‘It was part of the package; it was a ploy if you like,’ he says, hinting that he was as devious – or clever – then as he is now, in his current role as the man who holds the keys to the Secret Squirrel Club. ‘That bike had actually been to more than one World Cup before the Olympics,’ reveals Boardman. ‘But I hadn’t ridden it – Bryan Steel had. But because Bryan only finished eighth on it, nobody really noticed. In the end, yes, the bike got lots of publicity, probably more than me, but people still remember it and talk about it today. So I don’t regret that at all.’

In Ile de Ré, meanwhile, the sixteen-year-old Hoy, fanatical about cycling, and by now becoming interested in track cycling, genuinely was interested in the fact that a British rider – and not just a space-age bike – was in the final. ‘I remember being so excited about the Olympics,’ recalls Hoy. ‘The final was in the evening. We didn’t have a television where we were staying so I’d been listening to Boardman’s progress on the radio thanks to the BBC World Service. I remember calling my dad to come, because the final was on. And I remember listening to the final, hearing Boardman win, and being so inspired that I went straight out on the mountain bike I’d hired. I did ten miles flat out on that bike every day, and I’d already been out earlier in the day. But I went out and did it again.

‘It’s funny, I’ve watched that Olympic pursuit final since then, and it bears no relation to my memory of it. The images don’t remind me of how I felt at the time.

‘After that holiday we went straight to the British track championships in Leicester. I’d just started riding the track. But Boardman was there with his Lotus bike. I rode round behind him for a few laps and sneaked into a photo. I remember being completely in awe.’

Boardman’s Barcelona success acted as the launch pad not only for Boardman, who was propelled into a professional career on the continent, but also for his coach, Peter Keen, and, ultimately, you could argue, for the sport in the UK. What Keen did with Boardman he eventually replicated, on a far bigger scale, with the British team. In 1997 he was appointed by the British Cycling Federation to devise a ‘World Class Performance Plan’, which – in a revolutionary development – would receive millions in National Lottery funding. For the sport of cycling, things were about to change, and Hoy would be one of the main beneficiaries – indeed, he would be integral to the programme that Keen established. But no one – perhaps not even Keen – could have foreseen how dramatic the change would be.

Back in 1992, although Hoy had only just started riding on the track, he had actually been a competitive cyclist since the age of seven. Like so many children of the Eighties – he was born on 23 March 1976 – it was BMX-ing that provided the introduction.

The BMX bike was a child of the 1980s, just as Wham! or Grange Hill were. (Indeed, to emphasize how closely associated with the Eighties it was, the first official BMX race in Britain was staged in August 1980, and the international body set up in 1981.) But the sport was also treated as a child by the sporting authorities, being so far outside the mainstream that you would have thought it was a different sport: a BMX might as well have been a horse as far as cycling organizations were concerned. While thousands of kids competed up and down the country, and millions were inspired by the film BMX Bandits, not to mention the BMX chase scene in E.T., the conservative bodies that ran cycling ignored it, and them.

It was E.T. that snared Hoy. As he told his school magazine in 2004: ‘I saw the film E.T. and became hooked on the BMX craze.’ The film’s famous BMX scene, with Elliot and friends smuggling E.T., wrapped in a blanket and sitting in a handlebar-mounted basket, epitomized the appeal of the BMX. The scene, in which the kids evade their adult pursuers, summed up what the BMX represented: namely, freedom and escape – escape from adults, that is.

The adults are made to look silly, relegated as they are to the role of car-imprisoned spectators while the kids flee over what looks suspiciously like a purpose-built BMX race track. And then, of course, comes the serious ‘air’ – they take off. It provides the most famous image from the film: BMXs being ridden by a gang of kids (accompanied by an extraterrestrial creature) into the night, silhouetted against the moon. ‘This video makes me wanna’ ride my BMX again,’ is one comment below ‘E.T. the chase scene’, which inevitably features on YouTube. ‘Anybody who says they don’t hum the theme [to E.T.] while riding their bike is lying,’ says another. Absolutely.

But for Hoy it wasn’t all fun and games. The BMX racing scene was deadly serious and furiously competitive. So was he. ‘My first bike was one I got at a jumble sale,’ says Hoy, though his mother, Carol, corrects this. ‘I got him his first BMX at a jumble sale,’ she says. ‘I’d gone on the bus, so I couldn’t take it home – I had to get a friend to put it in her boot. It cost £5, I think.’ Hoy remembers that the first bike was ‘stripped down by my dad, who sprayed it black and put BMX stickers and handlebars on it. I snapped the frame after a month or so, doing jumps off planks of wood on bricks. I then got another bike, which was a neighbour’s daughter’s old bike. My dad gave it the same spray treatment and put on the same bars. But I bent the frame of that one.’

When he started racing – ‘I was second in my first race,’ says Hoy – a better bike became a priority. He spotted the machine he wanted in the window of an Edinburgh bike shop: a black and gold Raleigh Super Burner. It cost £99. ‘Too much,’ said his mother. She explains: ‘I said, “When you’ve saved up half the money, your dad and I will pay the rest.” He did it in no time. He was very clever. If we had people round for dinner, then Christopher would come in to show face, and then he’d talk about his BMX-ing, and how well he was doing, and he’d say, “There’s a bike I want but I have to pay half myself …” and the uncles and aunts would feel sympathetic and slip him a fiver.’

‘I waited until they’d had a drink or two,’ reveals Hoy, with evident pride.

Hoy’s father, David, was a great supporter of his son’s first outings as a BMX racer with Edinburgh club Danderhall Wolves. ‘He had a great start in Scotland, but then we went on holiday to the south of England and all these kids turned up on their £500 bikes,’ says David. ‘Chris was still on his Raleigh Super Burner. He got hammered. He was really pissed off. I thought, well, if he’s going to be serious about this then he should be on a better bike. The Burner was a toy, really.’

With a serious bike – a ‘SilverFox’ – he decided to join a ‘serious’ team. David Hoy explains: ‘There was a shop in Edinburgh, Scotia BMX, which had a wee team which Chris joined, and they contested races all over the country – in England too. With Chris at first it was the case that the further he travelled the more he got beaten and the harder he worked.’

David says he wasn’t a pushy parent, just a supportive one. It would be difficult to imagine him as a pushy parent – his enthusiasm is tempered by a zen-like calm. ‘I learnt a lot about child psychology from travelling with him and seeing other kids and their parents,’ he muses. ‘The Italians were especially interesting. If their kids came over the line and they hadn’t won, they got beaten – literally. I didn’t think that was the way to get the best out of them.

‘I didn’t put any pressure on. BMX was just a wonderful sport for kids. He did the cycling bit and my hobby was to look after the bike. On a Wednesday night I’d have the bike on the kitchen table, stripped, bearings out, the works, and then rebuild it for the weekend. I always loved taking bikes to bits.’

Carol Hoy, a bubbly woman with a sparky sense of humour, was sanguine about the weekly transformation of the kitchen table into a workbench. ‘I just thought that it was a lovely thing for a father and son to do. They spent whole weekends together, travelling mainly, and I used to only get involved in the local races, when I did the catering. I made burgers – BMX burgers, I called them. I told them they’d make them go faster. They were very popular.’

George Swanson, whose son raced with Hoy, was the man in charge of the Scotia BMX team. ‘We must have been one of the most hated teams in the history of cycling,’ he laughs. ‘I mean, Christ, talk about parochial! We were accused of signing up all the good kids – cherry picking. We sponsored riders from all over Scotland – Craig MacLean was one of our riders – and we took them down south to race. But when they raced in Scotland they rode for their local track. The idea was not to concentrate on the Scottish scene but to venture further afield, set our sights a wee bit higher. We had a yellow Bedford minibus and every weekend we had them away racing: Preston, Crewe, Bristol, you name it.’

‘People used to say, “You’re mad, how can you possibly take a kid 1000 miles at the weekend?”’ says David Hoy. ‘But actually Chris used to get more sleep on a race weekend. If I was taking him, we had a big Citroen estate car. I had a bit of foam cut out, and we laid that in the back of the car. What happened then was that he’d go to bed at 8 p.m., just like normal, then I’d wake him at 1 a.m., and carry him into the car. He’d go back to sleep and sleep all the way, while I drove. The furthest we went in a day was Bristol. We’d get there about 6 o’clock on the Sunday morning and he’d go out and practise for a couple of hours – the other kids would have been practising on the track on the Saturday. He would race all day. Then we’d leave about five; stop for a meal; he’d get in the back and go to sleep – and when we got home I’d carry him up to bed. So he used to get two twelve-hour sleeps.’

‘I didn’t get any. I was usually pretty tired on a Monday,’ David adds.

Swanson is interesting on the young Hoy-as-competitor. ‘The Chris you see now is nothing like the Chris we saw back then,’ he says, smiling. ‘He seems very calm now, totally in control and great in the high-pressure situations, but back then there was a kid from Musselburgh [near Edinburgh] who put the fear of God into him.

‘His name was Steven McNeil. McNeil always beat Chris in Scotland, though he never went south of the border. But I remember on one occasion we turned up at Chorley, after leaving about three in the morning. Chris and my son Neil went to register and Chris came back almost in tears. “Dad, Dad, Dad!” he said. “What?” says David. “He’s here.” “Who’s here?” “Steven McNeil’s here!”’

Swanson laughs: ‘He’d seen a red helmet – McNeil always wore a red helmet. But we went and checked – it wasn’t McNeil. It was strange, because Chris didn’t get involved in the mind games or worrying about his other competitors – apart from one: Steven McNeil. He was his nemesis. If he was there he cracked up. That time at Chorley, Chris didn’t want to race. But as soon as we told him he wasn’t there he was okay.

‘I saw Steven McNeil a couple of years ago,’ continues Swanson, ‘and I said to him: “If you ever run into Chris, tell him you’re thinking about making a comeback and taking up track racing, and watch his face go white.”’

Swanson had first spotted Hoy on a BMX when he was seven, and still on his Raleigh Burner. ‘He was out of place; everyone else was on proper BMXs, but you’re looking at this kid, and he stood out because he was actually keeping up with kids older than him. I went over and spoke to Dave and said, “Do you mind if we try him on a proper BMX bike?”’ He became a regular member of the Scotia party that travelled down south. ‘They were long weekends,’ says Swanson, ‘but bloody enjoyable.’

Hoy’s competitiveness was apparent to Swanson, which didn’t make him unique, but Hoy did stand out in one respect. ‘He was a ferocious competitor,’ says Swanson, ‘they all were. There were lots of tears, tantrums, but what made it worse was you had a van load of kids aged from about seven to ten, and it was fine and dandy if they all won, but if only one or two of them won, then you had a problem. You’re trying to be happy for the ones that have won and at the same time not go overboard because of the poor buggers who are sitting there with their noses out of joint. It was a difficult balance.

‘Chris’s reaction to defeats was interesting, though, because he was different to the others. If my son won, he was hyper. If he was beaten, he wouldn’t talk to anybody, especially not me, and he wouldn’t be in a mood to listen. Like most kids, it was one extreme or the other. But if Chris was beaten he would have a discussion with his dad about why he was beaten: whether he’d made a mistake in the start gate, or Dave geared him wrongly, or he got the line wrong going into the corner – whatever it was, there was always a rational conversation with his dad on the way back up the road, even at eight or nine years old, about why he was beaten. I remember being struck by it at the time. His reaction to getting beaten, or indeed winning, wasn’t the reaction you’d get out of other kids of that age. I think some of it was down to Dave. He’s not your pushy parent. You’d see a lot of parents getting torn into their kids, shouting, “What happened? I’ve driven 200 miles to bring you here and you made a complete arse of it!” Dave was always very calm and rational. He’s quite technical and logical. He’s also one of these great theorists, which could be more a hindrance than a help – sometimes he got carried away with his theories about gear ratios and so on.’

Swanson can only recall one occasion when Hoy became upset and emotional. On the occasion in question they were returning to Scotland following a triumph: Hoy had won, and the handsome gold trophy sat in pride of place on the dashboard of the van. Slowly, though, as they travelled north, the trophy’s shape became distorted – it melted. ‘The heater was on,’ explains Swanson. ‘It was plastic, of course, with a BMX rider on top. Chris was crestfallen when he saw this piece of molten plastic. He was eight and it was like the bottom had dropped out of his world.’

While in Scotland Hoy was ‘head and shoulders above everyone’ – apart from McNeil – in England it was a different story. There was another nemesis there: Matt Boyle, British champion an incredible twelve years in a row, European champion, and a silver medallist in the world championships. Younger still, and an even bigger player in the BMX scene, was the prodigious David Maw.

Everyone I talked to about BMX-ing mentioned Maw. He was a big star, and a three-time world champion, with an eight-year-old ego – it seems – to match. ‘In one race they were all at the start gate, up on the pedals, ready to go, when David Maw sticks his hand up,’ recalls Swanson. ‘So all the riders have to come down off their pedals, and David Maw starts doing stretching exercises! He was eight years old! The other kids were looking at him, rattled – which was his intention, of course. But he knew how good he was, and it worked. He was unbeatable, huge – there was a BBC documentary made about him.’

Tragically, Maw was killed in a car crash in 2000. And it seems he wasn’t the only one – a remarkable number of former BMX prodigies have met untimely deaths. ‘It’s quite an eerie world,’ says Hoy’s former rival, Matt Boyle, who continued to race BMX as a professional in America until 1999, when he was twenty-three. ‘A lot of people have been and gone.’