Полная версия

Imperial Vanities: The Adventures of the Baker Brothers and Gordon of Khartoum

IMPERIAL VANITIES

The Adventures

of the Baker Brothers and

Gordon of Khartoum

BRIAN THOMPSON

Dedication

To Elizabeth

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

List of Maps

Preface

Prologue

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

Keep Reading

Index

Other Works

List of Illustrations in Text

Books Consulted

Copyright

About the Publisher

List of Maps

Old Map of Ceylon from Skinner, T., Fifty Years in Ceylon, 1891.

Map of Zambesi with annotations by Livingstone © AKG London.

Nile map from Elton, Fifty Years in Ceylon, 1954.

Livingstone’s real map of watershed from Jeal, T. Livingstone, 1973.

Preface

This book is the interweaving of three remarkably self-willed lives. The careers of the two Baker brothers and Charles Gordon crossed and recrossed, very seldom in England itself, more usually at the eastern end of the Mediterranean (on occasions even further afield) coming at last to a tragic denouement in Egypt and the Sudan. They were Victorians with a taste for the heroic who made their friends and enemies from among the same restless kind. So, in these pages, we find also the enigmatic traveller, Laurence Oliphant; the explorers James Hanning Speke and Richard Francis Burton; the missionary David Livingstone; and soldiers as wildly unlike as Major-General Sir Garnet Wolseley and the irrepressible Captain Fred Burnaby.

There is a common connection, in that all these men were servants of Empire. Even Burton, such an inventively bitter critic of his own country and enemy to most of what we usually label Victorianism, put on his KCMG decoration for the first and last time in June, 1887, and celebrated Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in the grounds of the consulate in Trieste with these ringing words: ‘May God’s choicest blessings crown her good works!’

That particular weekend, toasts like this were uttered in every British embassy and consulate across the globe, as well as all the Queen’s dominions. As the sick and world-weary Burton himself put it, in a sudden and late flowering of imperial sentiment ‘May the loving confidence between her Majesty and all English-speaking-peoples, throughout the world, ever strengthen and endure to all time.’

The God that was invoked was held without question to be an Englishman. God the Englishman had subjugated half the world, bringing the blessings of civilization to heathens considered in desperate need of it. This is the background theme to much of what you are about to read. There could hardly be a greater vanity. Joseph Conrad was enough of a genius to look into its psychological first cause:

‘It is better for mankind to be impressionable than reflective. Nothing humanely great-great, I mean, as affecting a whole mass of lives – has come from reflection. On the other hand you cannot fail to see the power of mere words: such words as Glory, for instance, or Pity … Shouted with perseverance, with ardour, with conviction, these two by their sound alone have set whole nations in motion and upheaved the dry, hard ground on which rests our whole social fabric. There’s “virtue” for you if you like!’

These words, which were written to preface Conrad’s own experimental autobiography, A Personal Record, published in 1908, put the case admirably for the present book. Under only slightly different circumstances, a different throw of the dice, he might have applied them to the revolutionary politics of his father, Appollonius Korzeniowski. But in 1886, Conrad became a naturalised British citizen and at the time of the Jubilee and all its imperial celebration he was sailing about the Malay Archipelago, his eyes wide open to what brought white men to the ends of the earth – and kept them there.

My main intention has been to tease out the connections between three men, their lives and times. But there is also a desire to replicate what was itself a minor Victorian addition to the art of the book, one that has given pleasure right down to the present day.

As the story opens out, little by little a seemingly solid picture arises, in which elements that have no clear immediate purpose bend and unfold until, when the covers are finally laid flat, a man in uniform stands at the steps to a Governor’s palace. One hand is drawn across his chest in a gesture of fidelity to God and in the other a revolver dangles. Many intricate pleats and folds of coloured paper have brought him to life. By the strange compulsion we have to know about these things, the moment that is illustrated is also the moment of his death.

Nothing can make the little cardboard figure turn away, any more than the rush of all those turbanned men can be halted. The death of General Gordon had, for Victorians, all the elements of terror and pity evoked for us in a later age by the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Among Gordon’s contemporaries, for months, then years, the flux of history seemed, as it were, to shudder in its course. And then, inevitably, the story dwindled, along with the vanities that brought it into being. The two Baker brothers and Charles Gordon, who they were to each other and what constituted their life achievements, the joy they had of the world and its sorrows, fell like stones into the waters of the Nile.

I should like to thank Yvonne and Anthony Hands for many hours of genial encouragement in the writing of this book; John Crouch and Thomas Howard for some helpful pieces of research; an exemplary literary agent, David Miller, and not least Arabella Pike, an editor whose zestful enthusiasm for a good human interest story never sleeps. Finally, the work is dedicated, not without an element of apprehension, to a writer I have greatly admired for more than thirty years, whose good opinion is always worth having.

Prologue

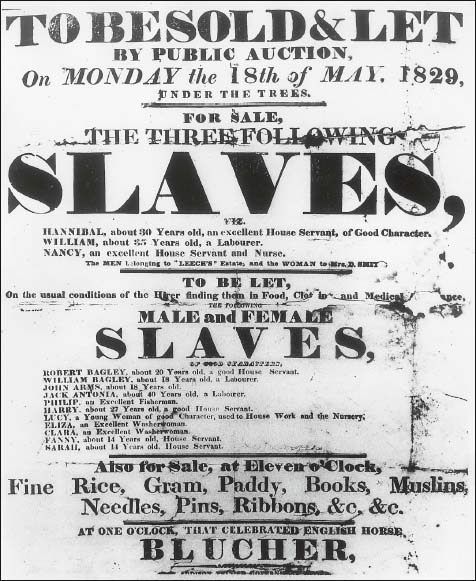

In 1815 a specially severe hurricane hit the island of Jamaica, tearing hundreds of houses and shanties from their foundations and dumping them in the sea. Over a thousand people were drowned or simply disappeared from the face of the earth. When the news was carried back to England, the only anxiety raised was what consequences there might be for the sugar plantations, for the Bristol and Liverpool merchants who controlled the trade realised at once that the victims of the hurricane were for the most part black. Jamaica was a slave island – the most ruthless and successful of them all – and the death of so many people was counted simply as additional loss of property. There was a verb much used whenever disaster of this magnitude occurred among the black population: the agents of the great plantations talked calmly about the need to ‘restock’.

To be British in Jamaica at that time was to live at the edge of things, almost but not quite beyond the reach of Europe’s civilising virtues. Whatever law that was enacted at Westminster touching the island’s affairs arrived in the Caribbean like ship’s biscuit, in a weevilly condition. For example, when it was seen that Parliament intended, after unrelenting effort by William Wilberforce and his parliamentary supporters, to bring about the abolition of slavery, one response of the planters was to encourage their women slaves to marry and end the common practice of abortion. They were looking ahead. If they could not at some time in the future import slaves, they would need to factory farm them on site.

After the Act of 1807 it was a crime for a Briton to buy a slave or transport one on a ship bearing the British flag. Nothing much changed locally. Beautiful though the islands might be, seen as a landfall after a wearisome Atlantic crossing, a miasma of ignorance and stupidity hung over them all. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel had already provided the most telling example of how difficult it was to think straight in the West Indies. In slavery’s heyday it was quite usual to brand newly acquired human animals as one would cattle and the SPG asserted its ownership and high purpose at one and the same time. Its slaves were seared across the chest with a white-hot iron bearing the word SOCIETY, without causing the slightest intellectual or moral embarrassment to anyone. For many years those who defended the institution of slavery held to the opinion that its victims were happier and better looked after than the poor of Europe. This point of view was one readily adopted by visitors to the islands, who confined their acquaintanceship to house slaves, whose servitude was – at any rate on the surface – uncomplaining.

The irrepressible memoirist William Hickey made a false start on Jamaica when he was a young man. Sent out by his father in 1775 and speedily frustrated in his attempt to be admitted to the Jamaica Bar, he whiled away his time at parties and drinking sessions, making visits to plantations and reporting what he saw with an uncritical eye. On arriving at a Mr Richards’s estate he was greeted by 500 slaves in an apparent ecstasy of happiness. ‘They all looked fat and sleek, seeming as contented a set of mortals as could be,’ he commented. This was something his host ascribed to a particular style of management. ‘He was convinced by his own experience that more was to be effected by moderation and gentleness than ever was accomplished by the whip or punishments of any sort.’ Hickey was easily persuaded but agreed to go with Richards next day to a neighbouring estate nine miles distant. There they found a girl of sixteen tied to a post being whipped half to death by a young manager. She had refused his sexual advances. Mr Richards’s indignation was great. Such brutality was bad for business and it showed in the ledgers.

‘The annual produce until the last five years was five hundred hogsheads of the very best sugar and four hundred puncheons of rum [he explained to Hickey], whereas now it yields not one third of either and is every year becoming worse, the mortality among the slaves being unparalleled, and all this owing to a system of the most dreadful tyranny and severity practised by a scoundrel overseer.’

Though the two unexpected visitors intervened before the girl could be killed and the story ended with the arrest and death of her tormentor (he was shot trying to escape from his soldier escort while on his way to Kingston), it did not occur to Hickey to question, then or ever, whether slavery under any guise, benign or not, was acceptable. This sprang not from ignorance but a socially conditioned indifference. Hickey was no stranger to foreign parts. He had already sailed as a cadet in the East India Company army to Madras, found he did not like it, and came home again via Canton and Macao. Nothing he saw of other countries and peoples made a mark on him. His patriotism was of the hearty, negligent sort common to the age – he was most at his ease with his own kind, which he found in the guise of ships’ captains, bleak old soldiers and the better sort of commercial agent. As for the rest of the world, it was no more than a passingly interesting puppet show; in the end a tedious exhibition of local colour. Here, racketing round Jamaica, the ownership of one human being by another was as unremarkable and obvious as the weather. Only the most incendiary sort of crank would draw attention to it.

Very few Europeans had ever seen or could picture a free African. The ones who escaped their bondage on Jamaica and ran away into the mountains were not free, but criminal. Up there the dreaded Maroons held sway, their lives a reversion to their previous existence in Africa – simple and, when necessary, invisible. They lived in lean-to shacks deep in the forest, the sites indicated only by the smoke from their fires rising above the tree canopy and – from time to time – the eerie sound of signal drums. The white planters hired these Maroons to hunt down escaped slaves. When the most persistent of these were caught and executed, it was customary to display the severed heads on pikes set in some prominent place, to discourage crime and reassure the more nervous of the white population. It was just another part of the landscape.

There was an echo on the island of better things. Many plantations taught their more biddable house servants music and ate to the wailing of string quartets, or danced to the accompaniment of a black band got up in velvet livery, wearing powdered wigs. Several times a year the great houses would be a blaze of light, with patriotic bonfires and the discharge of fireworks to honour some royal birthday or distant feat of arms. The planters liked to celebrate and raise hell in this way for the same reason they might whistle crossing a graveyard. Death was very near. A major player in the affairs of the islands was yellow fever. In the three-year campaign that began in 1794 to capture Martinique, St Lucia and Guadeloupe, 16,000 European soldiers died of the fever and were buried in the rags of their uniforms.

Yellow Jack knew no boundaries. It was swift and remorseless. Seized with a chill, in three days a man would be blowing bloody bubbles from his mouth and nose, unable any longer to speak or sign. The fever had no friends and attacked rich and poor alike. To be posted to the Jamaica garrison was a sentence of death for many a ploughboy who had taken the king’s shilling. The hated Baptist missionaries who stirred up such agitation on the island in the name of love of their fellow man had a life expectancy of three years.

The obvious comparison was with the way the East India Company managed its trade. This was a different model of colonialism altogether. Again, William Hickey is a useful witness. Two years after his abortive trip to Jamaica he set sail for India again, this time to Calcutta and the Bengal presidency, armed with a bulging portfolio of introductory letters provided for him by his father’s distinguished London cronies. Though the administration was in temporary financial crisis, Hickey found his place. He was appointed Solicitor, Attorney and Proctor of the Supreme Court and began his new life as he meant to go on, by commissioning a £1000 refurbishment of a house he selected as appropriate to his station. He purchased a new phaeton to drive about in, laid up the best wines in his cellar, gave extravagant parties – and started to shake the pagoda-tree. Though the glorious profits of the East India Company were tainted by slavery in all but name and the company was hardly there to exercise philanthropy, this was a far nobler occupation than the Atlantic trade could ever be. Hickey scrupulously names all his influential friends, being sure to indicate, wherever appropriate, the aristocratic titles they later inherited. India pleased him. There was honour to be had there, as well as wealth. Who could say that of the Caribbean, for ever tainted by its shameful African connections?

To all of which the sugar merchants had a single answer. The value of exports from the Caribbean colonies exceeded by far those from India and all other British possessions put together. By 1815 the West Indies exercised a virtual world monopoly on sugar. As for Africa, over which the abolitionists exercised their bleeding hearts as the true home of the black man, what was it but a trackless desert, without history, unlit by civilisation, contrary and pestilential? Even on the slave coasts, nobody had been more than a few miles inland, gliding along greasy brown rivers into an overwhelming aboriginal silence. Africa was an aside, an irrelevance. People wanted sugar. How it came to the table did not much concern them. Though the storm signals were flying for the Atlantic trade at home and abroad, it took an exceptionally far-sighted man to act on them.

In practice, every plantation was a petty kingdom where violence and terror was the norm and compassion as rare as window-glass. To whom did the governor report the abuses of the plantation system and with what consequence? For generations of ministries, Colonies had been bundled up with War – the one a consequence of the other. The loss of the American colonies made the humanitarian argument for an end to slavery very difficult for Britain to endorse. As the home country was forced to admit, in tolerating its calamities in the Caribbean it was also hanging on grimly to – and in the wars against the French doing all it could to increase – what was left of what it once had.

Soldiers and sea-captains had given Britain the original imperial advantage. So assiduous was Captain Cook in exploring the South Seas, for example, that the Whig wit Sydney Smith once estimated ruefully that if there was a rock anywhere in the world large enough for a cormorant to perch on, someone would think to make it British. It was a witty exaggeration of a not uncommon point of view, for the chief concern of home government was not the glory of overseas possessions, or the honour of their discovery, but how much it cost to garrison them. A common statistic of the early nineteenth century was that simply having a seaborne empire employed 250,000 men and tied up 250,000 tons of shipping. For many years the expenditure Britain was put to in its geopolitical adventures far exceeded revenue.

In this picture, Jamaica was strikingly different, a piratical treasure chest with the lid thrown back. Figures provided to the House of Commons in 1815 showed a value in exports of £11,169,661. Such public works as existed were maintained by a nugatory tax income of £1200. This was the plantation system at its apogee.

Everything that was so spectacular and fantastical about Jamaica’s wealth derived from the island’s dependence upon slavery. The standard agricultural implement was not the spade or the hoe but the cutlass. The standard punishment for an absconding slave was to lop off both ears. Nobody thought it of any great account. Visitors to Jamaica, who knew very well that fortunes were being made and fine country houses raised by the sugar merchants at home in England, were amazed by the coarseness and vulgarity of the planter society put in place to garner the profits of these great men. Most striking of all, the English men and women who lived on Jamaica and ran it for their absentee landlords affected to need nearly a third of a million slaves to sustain their position. Wellington had commanded an allied force of half that number to make himself master of all Europe.

This is how the story begins, on an island remote from Europe by 3000 miles. The word old-fashioned sits well with the Jamaican colonists. At the end of the war with Napoleon Britain controlled almost every Caribbean island – and who had won these great victories if not table-thumping, punch-drinking patriots cut from the old cloth, men William Hickey would be honoured to call his friends? Jamaica in 1815 was in triumphalist mood. It did not need capital – its wealth was in its labour force. It did not need fine gentlemen and, as it was making clear in its own surly and combative way, it did not need evangelical ministrations either. Put simply, Jamaica did not need improvement.

This shortsightedness was to be its undoing. Fifteen years later the value of sugar fell from £70 a ton to £25. In 1833, a law enacting the complete emancipation of the slaves changed the nature of the trade irrevocably. The unimaginable came to pass. The old planter society, which seemed as permanent and reliable as sunrise, was soon enough nothing but a romantic ruin. The factor in play here was much more important than the price of sugar. The reforming zealotry of a new age turned its mind to overseas possessions and found them wanting. The haphazard collection of islands and factories, plantations and anchorages was, within a generation, transformed. The Empire, which before had hardly merited its capital letter, became a single thing, an idea: in the hearts and minds of this new age, a crusade.

The people whose lives make up this book were not law-makers; neither were they in any sense radicals. They were Victorians of a particular stamp – adventurous, at times maddeningly complacent and, as far as feelings for their country were concerned, sentimental to a fault. None of them went to university – two of them were soldiers – and it could be argued that what we see in their experience is merely the exchange of one form of naivety for another. Certainly their patriotism was unquestioning enough to jar a modern sensibility. ‘Hurrah for old England!’ one of them cried as the scarecrow figures of Speke and Grant tottered into Gondokoro on the Nile, after walking from one hemisphere to the other. This is a shout whose echo has died completely, except perhaps on foreign football terraces, where the Union flag is more likely to be worn as a pair of shorts than a banner snatched up in the heat of battle.

What distinguishes these men is something new to the history of the nation. To their undoubted bravery was added the utter conviction of being chosen for a purpose even a child could understand. Throughout the nineteenth century there existed the belief that a Briton was the summit of God’s creation and the instrument of His will. This was never so clearly demonstrated as when he was abroad. Once a more or less random collection of properties – in which, for example, it could be contemplated that to exchange the whole of Canada for the strategic anchorage of St Lucia was a sensible trade with France – the Empire became the expression of a divine purpose. Nor was dominion over other people simply for economic advantage.

Let us endeavour to strike our roots into their soil, by the gradual introduction and establishment of our own principles and opinions; of our laws, institutions and manners; above all, as the source of every other improvement, of our religion and consequently of our morals.

This is Wilberforce, writing about India. The great evangelical Christian is indicating how not just India but the whole world was to be set free – by imposing upon it, however sympathetically expressed, a superior way of being. If in the end breechloading rifles and gunboats were the swifter teachers of this great lesson, it had deeper and, to such as Wilberforce, nobler origins. It started with the determination that nothing should be left undone to help the peoples of the world understand that their own histories, their own cultures and religious beliefs were mere shadows. The men whose story this is were evangelicals like Wilberforce only in this one sense: they took the missionary zealotry implicit in evangelism and expressed it in what seemed to their age heroic action. They were that new thing that animated Britain for a hundred years: they were imperialist romantics. Their virtue was in their character.

A young man called Samuel Baker visited Jamaica in the year of the great hurricane to inspect his family estates. They had come down to him through his father, the redoubtable Captain Valentine Baker. Thirty years earlier, while commanding a mere sloop, Captain Baker had engaged a French frigate, forced it to strike its colours and then brought it into Portsmouth in triumph. (The unfortunate French captain, when he realised how small a vessel had overwhelmed him, went below to his cabin and cut his throat.) A French-built frigate was considered the acme of naval architecture and when the news was carried across country to Bristol, the merchants there made haste to present Baker with a handsome silver vase as a mark of their appreciation. The gesture was not entirely patriotic. At the time of this stirring engagement Captain Baker was sailing under letter of marque. A less polite way of describing his activities was to call him a privateer. Baker rose in the estimation of his employers and 1804 found him master of the Fame, as large an armed vessel as ever left Bristol under private commission. With his share of the profits he bought land – Jamaica land, tilled by black slaves.

![A Monkey Among Crocodiles: The Life, Loves and Lawsuits of Mrs Georgina Weldon – a disastrous Victorian [Text only]](/covers_200/39771021.jpg)