Полная версия

Great Victorian Railway Journeys: How Modern Britain was Built by Victorian Steam Power

GREAT

VICTORIAN

RAILWAY

JOURNEYS

KAREN FARRINGTON

© National Railway Museum/SSPL

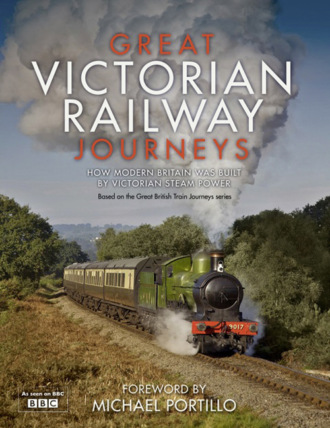

The first edition of Bradshaw's Railway Companion of 1840, with a pocket watch made c. 1870 by J. Atkins & Son of Coventry for a guard on the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway

© Old House books & maps

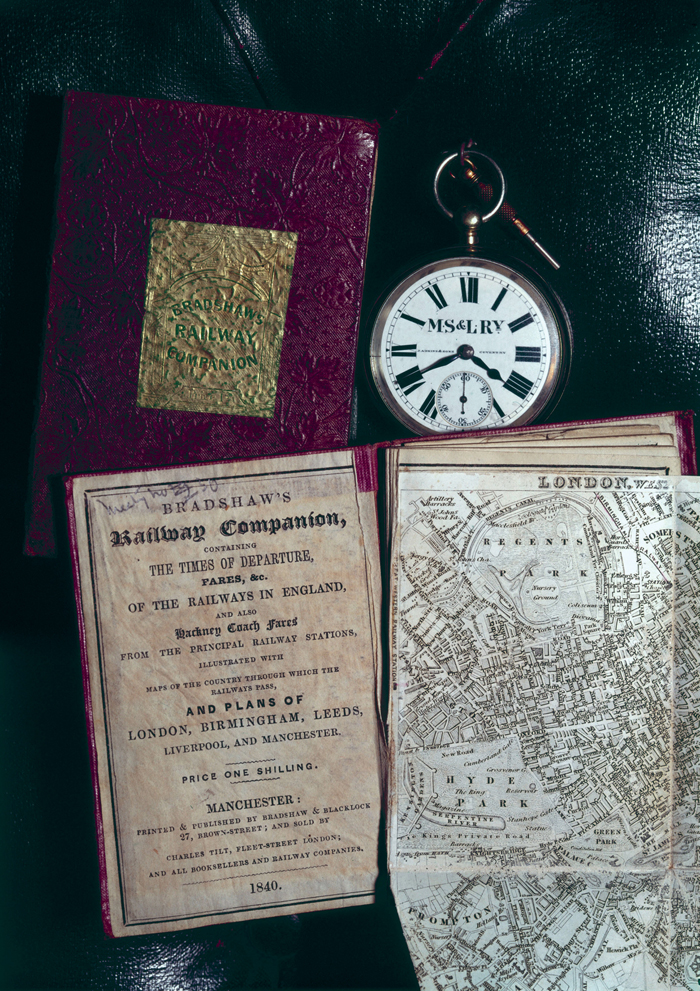

Bradshaw’s map of Dublin

Contents

Cover

Title Page

FOREWORD: By Michael Portillo - The Victorian Railway Revolution

INTRODUCTION: By Karen Farrington - The Genius of Bradshaw’s

JOURNEY 1: Excursions and Innovations - GREAT YARMOUTH to LONDON

JOURNEY 2: From Academia to Industry - OXFORD to MILFORD HAVEN

JOURNEY 3: A Royal Progress - WINDSOR to WEYMOUTH

JOURNEY 4: Border Country - BERWICK-UPON-TWEED to THE ISLE OF MAN

JOURNEY 5: Bradshaw’s Ireland - DUBLIN to BELFAST

Searchable Terms

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

© Old House books & maps

Bradshaw’s map of the Isle of Wight.

On an engine from the Downpatrick Heritage Steam Railway.

But on top of that, Britain underwent a physical metamorphosis. Where before, country lanes meandered, now embankments, tunnels and viaducts scythed through the landscape. Stations sprouted up, resembling Italian palaces, French châteaux or even Gothic cathedrals. Fearsome locomotives belching fire and steam frightened the horses as they sliced through city centres, or engulfed fields in flame as stray sparks set light to hay or stubble.

I remember being in awe and fear of steam locomotives. They were so big and noisy. Their wheels towered above me (especially when I was a boy, of course) and they were given to highly unpredictable behaviour, suddenly releasing clouds of water vapour with a hiss that made me jump. How did the Victorian middle classes in their finery, how did genteel ladies, cope with their sudden proximity to these roaring fireboxes, with being brought face to face with the industrial revolution?

How could they adapt to speed? At the Rainhill trials to choose a source of traction for the Manchester to Liverpool railway, Stephenson’s Rocket reached 30 miles per hour, a velocity previously unseen and hard even to imagine. The potency of the technology took some getting used to. At the inauguration of that line in 1830, William Huskisson MP, former President of the Board of Trade, left his carriage to greet the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington. The Rocket, running on the parallel track, struck him as he tried to scramble out of its path. A train transported him to the vicarage at Eccles where he died of his injuries.

When Isambard Kingdom Brunel opened his epic Box tunnel on the Great Western Railway, Dionysius Lardner, a professor of astronomy, was on hand to warn that if the brakes failed the train would accelerate and the passengers suffocate; and some at least believed him and alighted before the tunnel to continue their journey by more traditional means.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century William Blake wrote of ‘dark Satanic Mills’. The railways greatly accelerated the industrial revolution. George Bradshaw was enthusiastic about the railways, and the Handbook describes with admiration the dimensions of stations, tunnels and bridges. But the book’s depictions of iron-smelting furnaces lighting up the night sky sometimes bring the fires of Hell to mind. Bradshaw’s awareness of the social consequences of the industrial revolution suggests that Victorians saw that progress had brought both paradise and inferno.

Of Merthyr Tydfil the Handbook says:

Visitors should see the furnaces by night, when the red glare of the flames produces an uncommonly striking effect. Indeed, the town is best visited at that time, for by day it will be found dirty ... Cholera and fever are of course at home here ... We do hope that proper measures will be taken by those who draw enormous wealth from these [iron and coal] works to improve the condition of the people.

Quakers like Bradshaw tended to believe strongly that the industrialist owed a duty of care to his workers and their families.

To judge from the Great Western works at Swindon, railway magnates were appropriately paternalistic, housing the employees in model dwellings and supplying free rail travel for a family summer holiday in Devon or Cornwall. Many thousands would depart on charter trains, turning Swindon for a week into a virtual ghost town.

Train travel vastly broadened the horizons of working-class people. The mid-nineteenth century saw an enormous growth in travel and in resorts. As the railway navvies levelled the land, the railways levelled society. Those of modest means, who before train travel might scarcely have travelled beyond a 15-mile radius of home, could leave the smoke and grime of city life and enjoy the ‘salubrious’ (to use a favourite Bradshaw word) sea or mountain air. Town dwellers could for the first time enjoy fresh sea fish and a range of perishable farm products.

The railways threw up some interesting questions of etiquette, and drove social change. The usual requirement that ladies be chaperoned was difficult to enforce on trains. The new freedoms offered by rail travel contributed to increasing equality between the sexes. Nonetheless, women sometimes journeyed in fear, especially in compartments on trains that had no corridor. Some ladies secreted pins in their mouths as a way to deal with male passengers who in the darkness of a tunnel might attempt to steal a kiss!

Any worries that travelling by train was not ladylike were dismissed when Queen Victoria herself took to the tracks in 1842. Although she was nervous of travelling at high speed, she became a frequent railway passenger. The train conveyed her to Windsor, Osborne House and Balmoral. In 1882 it carried her to Nice, on the first of her nine visits to the Riviera. As though to emphasise how thoroughly the railway had entered national life, after her death on the Isle of Wight a train brought the Queen’s coffin home to Windsor.

Her lifetime covers most of the railway building that was done in this country. Poignantly, the last link of the West Highland line between Fort William and Mallaig (since made famous by the Harry Potter films) opened in 1901, the year of the Queen’s death. So, if you take a train today, it is extremely likely that you will travel on a route laid down in her day.

British national self-confidence reached its zenith in the Victorian era. The empire was vast and, to Bradshaw’s mind, the greatest that the world had ever seen. London was the biggest city on earth and Manchester could take cotton from India, turn it into manufactured garments and sell them back in India below the cost of local products. No hint of colonial guilt affected our patriotic pride.

That Britain was the first country to open an inter-city railway, that geniuses like Brunel and the Stephensons achieved engineering wonders, were evidence of the superiority of British ingenuity, science and entrepreneurship.

As today I travel along Victorian track beds I try to imagine the awe and pride that railways then inspired. Actually, if I look out the carriage window at the stations and viaducts that Victorian engineers erected, imagining it is very easy.

Michael Portillo

2012

© Old House books & maps

Bradshaw’s map of Oxford.

However, in 1837 a tipping point was fast approaching. During Victoria’s reign there was a headlong rush towards railway building that careered out of control, with profit rather than common sense at its heart.

With the rampant growth of railways, regimented tracks treated towns and fields with the same disdain as they splintered into an arbitrary network that reached from city to coast. The UK map was scored with lines that linked one town to the next – or sometimes bypassed entire populations for the sake of a country halt, depending on local politics. Before Victoria’s death in 1901 some 18,670 miles of track were on the ground.

© John Peter Photography/Alamy

Restored Caledonian Railway 0-6-0 steam engine 828 steams along the Strathspey Railway track between Broomhill and Boat of Garten.

One man had the vision to pull the hotchpotch of strands together to make sense of Britain’s railways for the travelling public. George Bradshaw was an engraver in Manchester whose first major work was a map of British canals, rivers and railways, published in 1830. In 1838 he began producing railway timetables which, four years later, began appearing as a monthly guide.

© Science Museum Pictorial/Science & Society Picture Library

George Bradshaw, c. 1850s.

One of the first challenges Bradshaw faced was the time lag between, say, London and the West Country, which amounted to some 10 minutes, with separate communities setting their watches by their own calculations of sunrise and sunset. Engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel had already identified the problem and insisted on standardising clock faces across the Great Western Railway network, using ‘railway time’. Bradshaw picked up the baton and made ‘railway time’ uniform for the whole of Britain for the purposes of his timetabling.

Eventually Bradshaw’s publishing stable included a Continental Railway Guide and a Railway Manual, Shareholders’ Guide. But it was the monthly guides that were best sellers and, after Bradshaw’s untimely death in 1853 from cholera, the publication continued to appear under his name. Indeed, it was published until 1961.

© Paul Mogford/Alamy

The station clock at Crowcombe Heathfield on the West Somerset railway line.

This book focuses on another Bradshaw publication, Bradshaw’s Tourist Handbook, published in 1866. Inside its pages lies a lyrical image of Britain as it was 150 years ago. There are both hearty recommendations and dire warnings for the Victorian explorer embarking on long-distance domestic journeys. For example, Bradshaw’s gives an emphatic thumbs-up to Gravesend, with a description that would make any casual reader want to hop on a train and visit:

Gravesend is one of the most pleasantly situated and easily attained of all the places thronged upon the margin of the Thames. It is, moreover, a capital starting point for a series of excursions through the finest parts of Kent and has, besides, in its own immediate neighbourhood some tempting allurements to the summer excursionist in the way of attractive scenery and venerable buildings.

But Cornwall, which today might be considered the brighter prospect of the two for travellers, is altogether less impressive through nineteenth-century eyes:

Cornwall, from its soil, appearance and climate, is one of the least inviting of the English counties. A ridge of bare and rugged hills intermixed with bleak moors runs through the midst of its whole length and exhibits the appearance of a dreary waste.

As intriguing as these descriptive passages are the accompanying advertisements, for ‘Davis’s Patent Excelsior Knife Cleaner’ and ‘Morison’s Pills – a cure for all curable diseases’. The 1866 fares for day trips and holidays are also advertised.

Excursions were a joyful hallmark of the Victorian age. Many people had more leisure time and spare income than ever before and they broadened their horizons by travelling across the country or the Channel to new resorts and to attend great occasions like exhibitions and major sporting events. For the railway companies, dedicated trains to resorts or events were a profitable way to use idle stock at off-peak times.

© Amoret Tanner/Alamy

A Victorian seaside excursion, c. 1890.

To travel to Dublin via Liverpool from Hull in 1866 cost the first-class passenger 43 shillings. It was 10 shillings less in second class. Return tickets to the Continent via Calais from London were £2 first class and £1 10 shillings in second. Meanwhile, a first-class ticket from Nottingham to Windermere was priced at 42 shillings, and 10 shillings less again for those in second class.

The virtues of Bradshaw’s guides in all their forms have long been recognised. Journalist and travel writer Charles Larcom Graves (1856–1944) penned the following verse, reflecting his own cosy association.

When books are pow’rless to beguile

And papers only stir my bile,

For solace and relief I flee

To Bradshaw or the ABC

And find the best of recreations

In studying the names of stations.

Certainly in those days before the advent of through tickets, Bradshaw’s Monthly Railway Guide was an often-consulted bible for travellers who industriously sought arrival and departure times during detailed journey planning.

No doubt the tripper clutching a Bradshaw guide would feel a rush of nerves as well as excitement in boarding the train, for the notion that railways were dangerous took a long while to subside and railway safety standards were poor by comparison with today. To compound matters, railway companies were reluctant to spend money on even basic safety measures, preferring to reward their shareholders rather than to protect their passengers and staff. Accordingly, brightly painted engines were kept whistle clean but might not be fitted with an adequate number of brakes. The prospect of a rail crash in Victorian times and death by technology invariably filled travellers with fear.

It wasn’t until 1875 that a Royal Commission on Railway Accidents was established. It fostered trials on different braking systems, with American-designed systems coming out on top. However, not all railway casualties were linked to crashes, according to railway writer and Royal Commission member William Mitchell Acworth.

Passengers tried to jump on and off trains moving at full speed with absolute recklessness. Again and again it is recorded, ‘injured, jumped out after his hat’, ‘fell off, riding on the side of a wagon’, ‘skull broken, riding on the top of the carriage, came into collision with a bridge’, ‘guard’s head struck against a bridge, attempting to remove a passenger who had improperly seated himself outside’, ‘fell out of a third class carriage while pushing and jostling with a friend’.

‘Of all the serious accidents reported to the Board of Trade,’ writes one authority, ‘twenty-two happened to persons who jumped off when the carriages were going at speed, generally after their hats, and five persons were run over when lying either drunk or asleep upon the line.’

Putting aside the dread of disaster, there was a lot of general discomfort to overcome, even for those travelling in first class. With as few as four wheels per carriage in the early days of rail, there was no sense of a rhythmic lull, more a violent vibration. Moreover, for decades carriages were unheated, although foot-warmers were available at a price on most routes. Initially only first-class travellers were permitted their use.

Until the mid-1840s third-class passengers were transported in open wagons that were sometimes attached to goods trains. In winter passengers were typically underdressed while subject to wind and rain, and might even suffer exposure. Travelling inside carriages modelled on stagecoaches was not without its disadvantages either.

© The Stapleton Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library

‘A Train of the First Class (top) and a Train of the Second Class (bottom)’ from Coloured View of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, engraved by S. G. Hughes and published by Ackermann & Co., London in 1832/33.

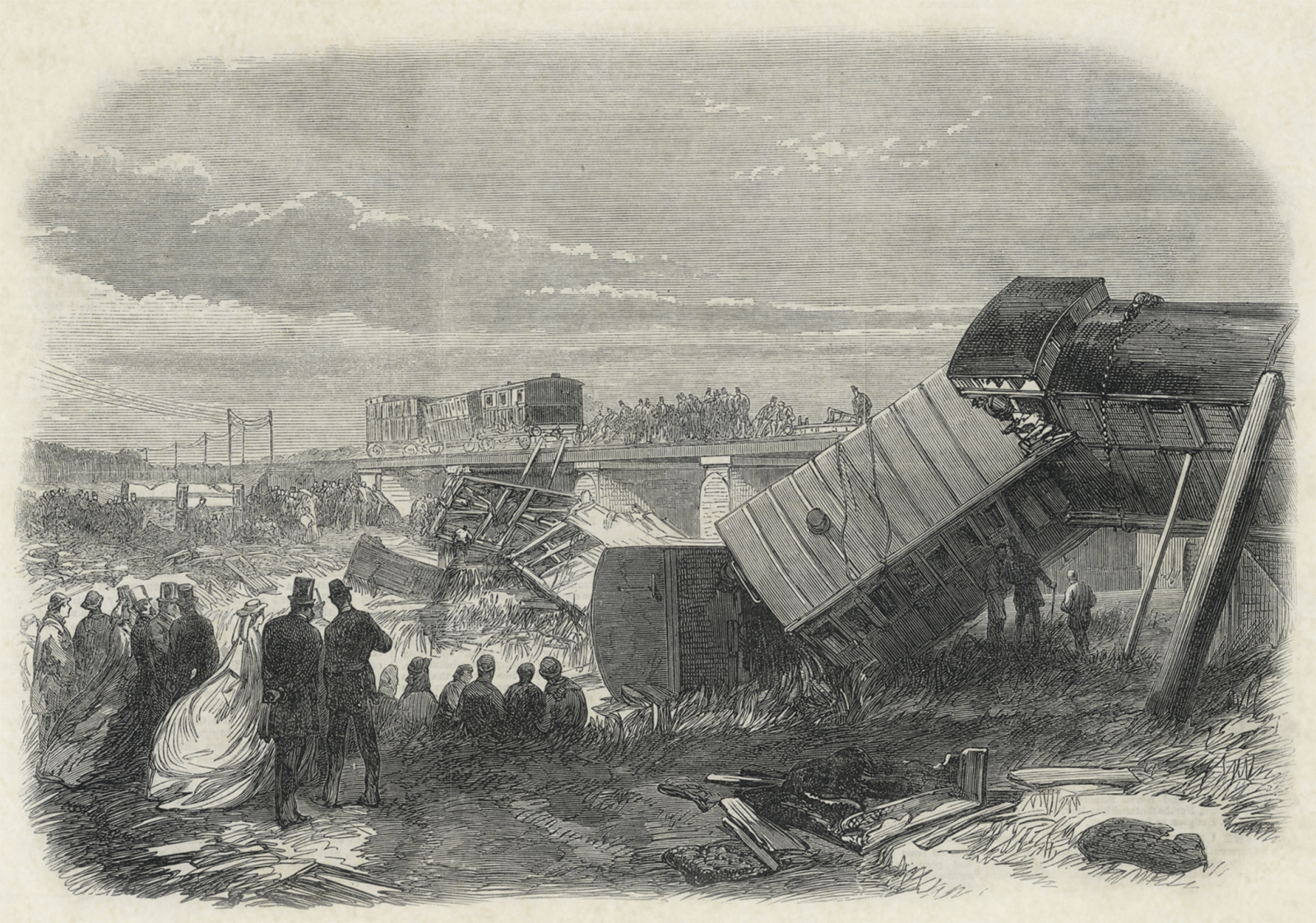

THE STAPLEHURST RAIL DISASTER

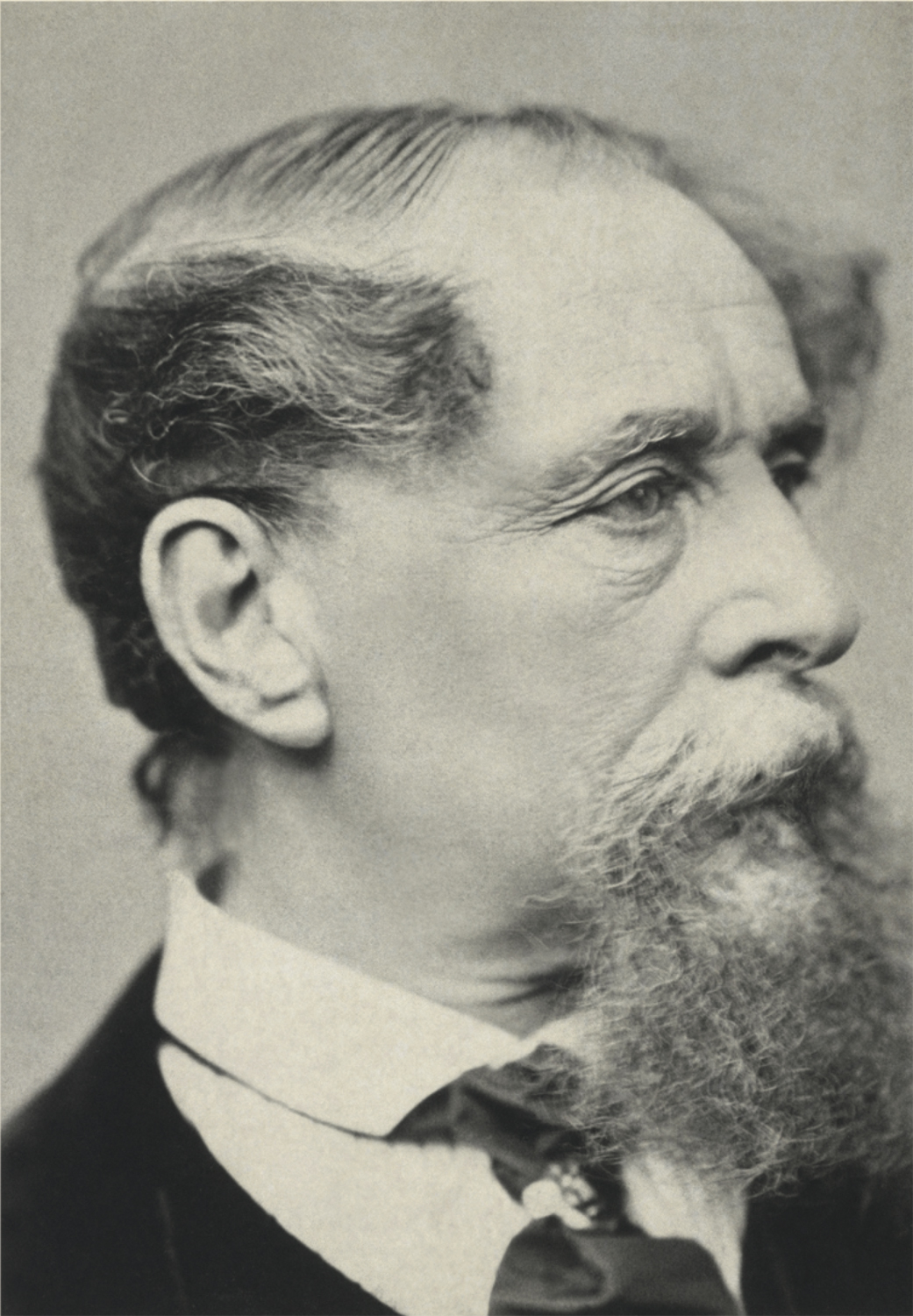

Author Charles Dickens showed remarkable presence of mind after he was involved in the Staplehurst disaster, but later he wrote about the long-term after-effects he suffered.

© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

Charles Dickens (1812–1870) in middle age.

On 9 June 1865 Dickens was returning from France aboard the boat train, heading for Charing Cross. Along the way, at Staplehurst in Kent, track was being renewed on a railway bridge by a group of ‘gangers’ or ‘waymen’, employed by the thousand across the country to repair and maintain track. (The remains of line-side huts where equipment was stored and tea was brewed for this unsung army are sometimes still visible today.)

The train was known as ‘the tidal’, because its timing varied with the tide that brought the ferries to their berth. According to foreman John Benge’s calculations, it would roll into view at 5.20 p.m. In fact, the train was two hours earlier than that and was bearing down on the fractured bridge at a speed of 50 mph. It was impossible to return the necessary track to its position in time.

With rails missing, the locomotive ploughed into the mud lying 10 feet below. The first coach almost went after it but lurched to a halt, balanced precariously between engine and bridge. Its coupling with the rest of the train snapped and another five coaches, travelling with momentum, piled into the gap, landing at all angles.

Ten passengers died and 49 people were injured. Dickens, who was in the first carriage, was uninjured and climbed out of the window. The author tended the wounded as best he could. One man died in his arms and he saw several other dead bodies as he picked his way cautiously through the injured, offering water and brandy.

He wrote about the shocking experience in a letter:

No imagination can conceive the ruin, or the extraordinary weights under which people were lying, or the complications into which they were twisted among iron and wood, and mud and water.

I have a – I don’t know what to call it – constitutional presence of mind and was not in the least flustered at the time … But, in writing these scanty words of recollection, I feel the shakes and am obliged to stop.

© Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans

The Staplehurst Rail Disaster: Dickens, Ellen Ternan and her mother escaped unhurt, but he suffered psychologically to the end of his life.

The crash left him at a low ebb. Three years later he wrote:

To this hour I have sudden rushes of terror, even when riding in a Hansom cab, which are perfectly unreasonable but quite insurmountable … my reading secretary and companion knows so well when one of these momentary seizures comes upon me in a railway carriage that he instantly produces a dram of brandy which rallies the blood to the heart and generally prevails.

Dickens died five years later, on the anniversary of the Staplehurst crash.

TO THIS HOUR I HAVE SUDDEN RUSHES OF TERROR, EVEN WHEN RIDING IN A HANSOM CAB, WHICH ARE PERFECTLY UNREASONABLE BUT QUITE INSURMOUNTABLE

© Look and Learn/The Bridgeman Art Library

The Comfort of the Pullman Coach of a late-Victorian Passenger Train by Harry Green (b. 1920).

If the atmosphere in the small railway compartments became fetid it was tempting to open the window. However, passengers risked being enveloped in smuts and steam from the engine rather than enjoying the bracing fresh air they’d sought. The question of whether or not to open windows on stuffy journeys was often the cause of fall-outs between passengers.

Borrowing an American idea, railway companies began to introduce more luxuriously appointed accommodation with restaurant facilities from the 1880s. Self-contained sleepers were on the rails from 1873. However, the first train with a corridor running its entire length wasn’t introduced until 1892. Until then lavatories were simply not available to third-class travellers, and guards were sometimes compelled to clamber along the outside of moving carriages.

© Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans

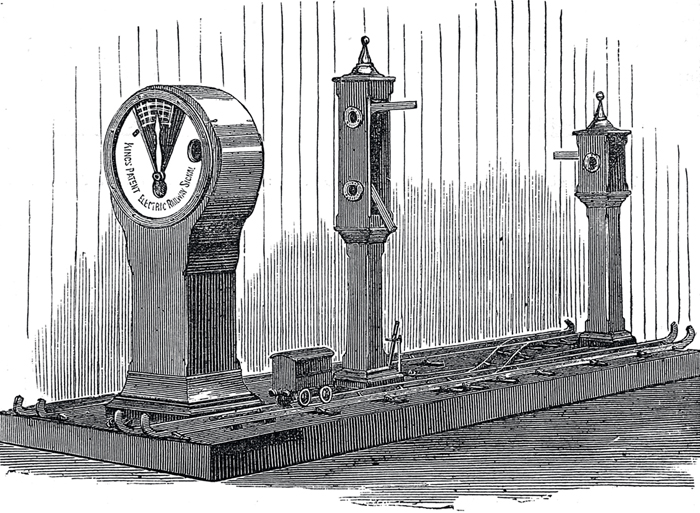

An electric signal for railways invented by a Mr King of Paxton, Derbyshire and exhibited at the Crystal Palace Electric Exhibition in 1882. The signal worked by passing electricity through a series of signal-posts placed along a railway line, which would activate a clock hand demonstrating the length of time elapsing between trains.

There’s no doubt that railways were evolving throughout the Victorian era, although not as quickly as some had hoped. Bigger engines were soon hauling more carriages, increasing capacity and cutting costs. However, they weren’t going much faster than early models. Until braking issues were resolved drivers were compelled to travel more slowly than they might have liked.