Полная версия

Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air

Great use, he thought, there might be made

Of these machines in his own trade;

Now o’er a fortress he might soar

And its condition thence explore

Or when by mountains, woods, or bog

An enemy might lie incog

Our friend would o’er their station hover

Their strength, their route, and views discover;

Then change his course, and straight impart

Glad tidings to his chieftain’s heart … 6

These were all to prove strangely prophetic.

5

The experience of ballooning is in a sense timeless. Man-carrying balloons are both extremely modern and extremely primitive devices. In their contemporary form, powered by stainless-steel propane-gas burners and using rip-stop nylon envelopes, they were virtually reinvented in 1960 by an American, Ed Yost, experimenting in Nebraska. His ideas were quickly taken up by Don Cameron and others in Britain and France.7 It should not be forgotten that these reinvented balloons were contemporary with the first moon landings and the earliest communication satellites.

But balloons are also ancient and symbolic devices. They have a long history, and a longer mythology, going back in various forms and dimensions thousands of years, to ancient civilisations in South America and China. There are vague accounts of man-carrying smoke balloons from the Yin dynasty of the twelfth century BC. The great scholar and Sinologist Joseph Needham suggested that Chinese of the fourth century BC used fire balloons for signalling in warfare, or perhaps for carrying love letters. There are rumours of shamanic balloon flights made by the priests of the pre-Inca civilisations. Peruvian funereal rituals involved sending corpses out over the Pacific by hot-air balloon, just as the Vikings would later send out their sacred dead by fireboat into the North Sea. The famous geometrical carvings on the Nazca plateau in southern Peru, some of them animal shapes stretching over four miles in outline, are only explicable if they were originally designed to be viewed from hundreds of feet in the air, so presumably by balloon.

It has been suggested that the Nazca designs were made by visiting aliens, hovering in flying saucers.fn3 But the modern balloonist Julian Nott successfully invented a huge smoke balloon, constructed purely from local materials, to prove that human beings could overfly and supervise the carvings even in the fifth century AD.9

The primitive and the sophisticated elements of ballooning are often combined. In this way the balloon may have both a practical and a symbolic function, for example when it is used as a means of escape. Among the most remarkable balloon escapes ever made was a flight across the East German border in September 1979. Its daring, and the idea of a symbolic flight from Communism to the free West, so caught people’s imaginations that it was made into an adventure film by Disney, Night Crossing (1982), starring John Hurt and Beau Bridges.

In March 1978 two East German men, Peter Strelzyk and Günter Wetzel, living with their wives and four children at Poessneck, near the East German frontier, began working on several ideas for escaping to West Germany. Strelzyk was an aircraft mechanic and electrician with his own workshop, while Wetzel was a builder and a gifted handyman. Both were brilliant at bricolage, endlessly resourceful and determined. Together they hit upon the idea of secretly constructing a home-made hot-air balloon in Strelzyk’s attic and workshop. There are various accounts of how they came up with this idea, but one is that Wetzel’s sister-in-law gave them an illustrated magazine article about the annual Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta, the most famous of all hot-air balloon gatherings, launched in New Mexico in 1972. After that they got all their technical information from the Poessneck public library.

Their balloon had to be very large, capable of lifting eight people to a height of at least five thousand feet, to avoid detection by frontier searchlights, and of carrying them at night over a distance of at least ten miles. They spent months surreptitiously assembling suitable materials, building makeshift propane burners and testing various potential balloon fabrics – including cotton sheets, umbrella covers, waterproof-jacket linings and tenting fabric. The work was shared, but Strelzyk specialised in constructing the burners and the sheet-metal balloon platform, while Wetzel worked on the balloon canopy and rigging. He sewed all the curved balloon strips, or gores, together on a pre-war, pedal-operated sewing machine. Everything had to be bought in small quantities from different shops to avoid alerting the network of Stasi informers; they drove as far as Leipzig to cover their purchases, sometimes claiming that they represented camping or sailing clubs. Their balloon trials were carried out at night in remote areas of the Thuringian forest.

In the end, with infinite patience and ingenuity, they built three versions of their escape balloon. The first, a sixty-foot-high cotton balloon with a capacity of seventy thousand cubic feet, failed to inflate properly, due to porous fabric and a weak burner using two domestic propane cylinders. It had to be abandoned and painstakingly destroyed in April 1978. After more than a year of experiments and setbacks, they came up with a second design with a better, four-cylinder burner and tighter fabric. But during this anxious time Günter Wetzel, increasingly haunted by the risks to his family, reluctantly withdrew from the scheme, and began to consider more conventional methods of crossing the border.

The second balloon was designed to take only the three members of the Strelzyk family. Symbolically, they chose American Independence Day, 4 July 1979, for their launch. But the balloon still lacked lifting power. It flew too low, became drenched by rainclouds, and began to sink earthwards just as the border came in sight. The Strelzyks crash-landed in the bare no-man’s land two hundred yards short of the actual frontier fence. By good luck they were just outside the frontier ‘death zone’, where the barbed wire, anti-personnel mines and automatic guns would have proved fatal. Astonishingly, the crumpled shape of the balloon was not immediately spotted by the border guards, probably because of the heavy rain. Under cover of darkness the three Strelzyks scrambled out of the wreckage, collected all the personal belongings they could carry, and somehow managed to slip back undetected to Poessneck, covering nine miles on foot before dawn. But the balloon equipment that they were forced to abandon meant that the Stasi had clues to their identity, and would soon be hot on their trail. Discovery within a matter of weeks was inevitable.

At this desperate moment, the two families joined forces again. Working around the clock, the Strelzyks and the Weltzers constructed a much bigger balloon using piecemeal sections of artificial taffetas and dress materials, hastily purchased from small shops all over East Germany. An electric engine was attached to the sewing machine, and the propane burner was redesigned. In a matter of six weeks they had a new balloon looking like a huge multicoloured quilt. When fully inflated it stood nearly ninety feet high, and had a hot-air capacity of over 140,000 cubic feet, double that of the previous balloon. Its burner was powered by four propane tanks feeding into a simple five-inch-diameter stovepipe, capable of producing a narrow, violent flame which at maximum pressure shot fifty feet into the air – within thirty feet of the inner crown of the balloon. This could in theory lift well over 1,200 pounds (544 kilograms), the equivalent of seven adults and a child plus all the balloon equipment. But everything depended on the durability of the home-made envelope, the strength and direction of the wind, and the general flying conditions (including air temperature and humidity) on the actual night of the flight.

Unable to obtain materials for a conventional wicker basket, they constructed instead an open metal platform four and a half feet square. The four propane cylinders stood in the centre of this platform, and the eight passengers carefully distributed their weight around them, having to crouch within inches of the platform’s outer edge. The youngest Wetzel was held in his mother’s arms. The ten guy ropes connected to the balloon were tethered to iron stanchions welded along the edges of the platform, which provided some handholds. There was also an outer guardrail made of loops of washing line, but this only came up to the adults’ waists. The stovepipe burner was ignited by a household match, and at full power burnt with a tremendous roar about six feet above the passengers’ heads, shooting flame high into the centre of the balloon. When this ‘flame-thrower’ was extinguished, they would float in absolute darkness and silence, standing virtually unprotected in the air, with no sound but the creak of the ropes against the balloon fabric, somewhere invisible above their heads. It was a magnificent, dreamlike, insane contraption. But it flew.

At 2 a.m. on the night of 16 September 1979, with a brisk eighteen-mile-per-hour breeze blowing towards West Germany, they took off from their secret base in the Thuringian forest, about six miles from the frontier. They cleared the fir trees, and with a tremendous blast from the propane burner, the balloon rose rapidly to 6,500 feet. But as it turned on its axis in the dark, they soon lost all sense of direction. Clinging together on the tiny metal platform, they peered down in silence, looking for car headlamps which would indicate roads, or the chain of lights which would mark the border.

After about twenty minutes, to their alarm, they suddenly saw searchlights springing up almost directly beneath them. They had the choice to drift downwards, steadily sinking but hoping to avoid detection in the dark, or to fire up their burner and try to climb clear. They chose to fire the burner, and with a huge sustained burst of flame, which they felt must surely be visible for miles around, rose to nearly nine thousand feet. Under either the increased heat or the air pressure, the crown of the balloon split. They began to sink again, but the balloon remained inflated, and by continuing to fire the burner until their propane ran out, they managed a crash-landing in an open field a hundred yards from a high-voltage pylon. Günter Wetzel broke his leg, but otherwise they were all unhurt, although they had no idea on which side of the border they had arrived. Peter Strelzyk walked over and shone a torch on the ‘Danger of Death’ sign fixed to the base of the pylon. It belonged to a West German electricity company. They had flown to freedom – and to fame – in exactly twenty-eight minutes. ‘We could have made it as far as Bayreuth,’ remarked Wetzel.10 fn4

6

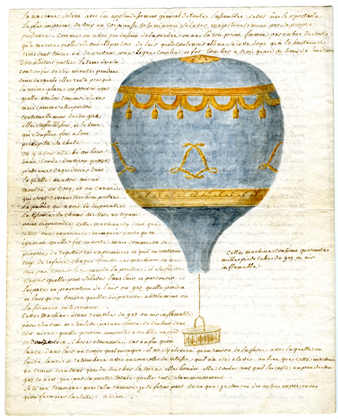

The theme of escape, either literally from some form of imprisonment, or symbolically from the troubles of the earth itself, constantly recurs in the history of ballooning. When Dr Alexander Charles made the first ever flight by a true hydrogen balloon, two hundred years before the escape of the Strelzyks and the Wetzels, on 1 December 1783, it was the feeling of absolute and almost metaphysical freedom that overcame him.

Flying with an engineering assistant, Monsieur Robert, Dr Charles launched from the Jardin des Tuileries in central Paris, and travelled over twenty miles north-west to the country town of Nesles. His balloon was a mere thirty feet high, but was equipped with a proper wicker basket, a venting valve, and sacks of ballast to adjust its height and control its descent. His departure was witnessed by nearly half a million people, among them the American ambassador, Benjamin Franklin. After they had landed safely at Nesles, Monsieur Robert disembarked, but Dr Charles remained in the basket. He then achieved the first ever solo ascent, rapidly rising in the lightened balloon to a magnificent ten thousand feet. From this vantage point he saw the sun set for a second time on the same day. It was a revelation.

Dr Charles’s brilliant account of this ascent was widely published in both Britain and France, and catches a euphoric tone which never quite disappears from subsequent balloon accounts. He had laid in supplies for an aerial journey of many hours – fur coats, cold chicken and champagne. But what he actually tasted was that existential substance:

Nothing will ever quite equal that moment of total hilarity that filled my whole body at the moment of take-off. I felt we were flying away from the Earth and all its troubles and persecutions for ever. It was not mere delight. It was a sort of physical rapture … I exclaimed to my companion Monsieur Robert – ‘I’m finished with the Earth. From now on our place is in the sky! … Such utter calm. Such immensity! Such an astonishing view … Seeing all these wonders, what fool could wish to hold back the progress of science!’ 12

Benjamin Franklin watched the launch through a telescope from the window of his carriage. Afterwards he remarked, ‘Someone asked me – what’s the use of a balloon? I replied – what’s the use of a new-born baby.’

The same sense of escaping into an utterly new world is displayed by Thomas Baldwin’s Airopaedia, or Narrative of a Balloon Excursion from Chester in 1785. This is his account of a single flight made on 8 September 1785, flying northwards above the river Mersey, from Chester to Warrington in Lancashire. It must be one of the most remarkable books about the experience of ballooning ever written. It also included flight maps, and the first aerial drawings ever made from a balloon basket.

Baldwin was one early pioneer of the existential attitude to ballooning, in which the idea that the ‘Prospect’ itself – the free ascent, the magnificent views, the whole ‘aerial experience’ – was the real point of flight. He believed that ‘previous Balloon-Voyagers have been particularly defective in their Descriptions of aerial Scenes and Prospects’. Consequently he took with him a battery of recording equipment: a variety of pens and red lead pencils, special ‘Ass Skin Patent Pocketbooks’, paints and brushes, drawing blocks and perspective glasses, telescopes and compasses. Airopaedia contained the first ever paintings of the view from a balloon basket, an analytic diagram of the corkscrew flight path projected over a land map, and a whole chapter given up simply to describing the astonishing colours and structures of cloud formations.

Baldwin also notices how the balloon responded to air currents arising from the earth beneath. His careful flight-mapping shows how it was constantly drawn downwards to follow the cool, curving airflows above the meanderings of the river. Similarly, the heady act of leaning directly over the side of the basket to paint, observe and measure makes him sensitive to shifts in shade and colour and perspective on the ground below.

One typical observation reads: ‘The river Dee appeared of a red colour; the city [Chester] very diminutive; and the town [Warrington] entirely blue. The whole appeared a perfect plane, the highest buildings having no apparent height, but reduced all to the same level, and the whole terrestrial prospect appeared like a coloured map.’13

Baldwin also writes wonderfully well about clouds, and the prismatic effects of light. He clearly perceives a whole new world opening out around him, and expresses a euphoric emotional reaction. Indeed, to keep these feelings within bounds, he writes of himself throughout his flight in the third person: ‘A Tear of pure Delight flashed in his Eye! of pure and exquisite Delight and Rapture!’ For him, ballooning instinctively combined both scientific discovery and aesthetic pleasure. But perhaps it should provide more? He could imagine the time when ‘aerostatic ships make the Circuit of the Globe’.14

7

The essential mystery of ballooning – the enigmatic meaning of the original dream – was there from the start. Almost a decade after its invention by the Montgolfier brothers, with flights recorded in many nations, including Germany, Italy, Russia and America, it was still not clear, either to the Royal Society in London or the Academy of Sciences in Paris, what the true purpose or possibilities of ballooning really were. Don Paolo Andreani had flown from Milan in February 1784; Jean-Pierre Blanchard and Dr John Jeffries had traversed the Channel in January 1785; Pilâtre de Rozier had died attempting the same crossing in the opposite direction with a composite hydrogen and hot-air balloon in June 1785 (thereby becoming the first scientific balloon martyr); Baron Lütgendorf had ‘partially’ flown at Augsburg in August 1786; and Blanchard had gone on to demonstrate ballooning in virtually every major city in Europe, finally crowning his international career with what he claimed was the first ever American ascent, from the city of Philadelphia in January 1793, carrying an ‘aerial passport’ endorsed by President George Washington, and successfully crossing the Delaware river into New Jersey.15

Yet all these ascents were essentially public spectacles and entertainments. ‘Flight’ itself remained a novel and surprisingly unexplored concept. What, in practice, could balloons actually do for mankind, except provide a hazardous journey interspersed with the fine aerial ‘Prospects’ that men like Dr Charles and Thomas Baldwin recorded so eloquently?

According to Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond, the Parisian promoter of the Montgolfier balloons, they might, for example, provide observation platforms: for military reconnaissance, for sailors at sea, for chemists analysing the earth’s upper atmosphere, or for astronomers with their telescopes. It is notable that most of these applications were based on the notion of a tethered balloon. In fact many of the Montgolfiers’ early experiments were made with tethered aerostats, held to the ground by various ingenious forms of harness, guy ropes or winches.fn5

The poet and inventor Erasmus Darwin’s first practical idea of balloon power was, paradoxically, that of shifting payloads along the ground. He suggested to his friend Richard Edgeworth that a small hydrogen balloon might be tethered to an adapted garden wheelbarrow, and used for transporting heavy loads of manure up the steep hills of his Irish estate. This convenient aerial skip would allow one man to shift ten times his normal weight in earth, but also in bricks or wood or stones. In fact it might cause a revolution in the entire conditions of manual labour.17

Similarly, Joseph Banks, the President of the Royal Society, had the initial idea that balloons could increase the effectiveness of earthbound transport, by adding to its conventional horsepower. He saw the balloon as ‘a counterpoise to Absolute Gravity’ – that is, as a flotation device to be attached to traditional forms of coach or cart, making them lighter and easier to move over the ground. So ‘a broad-wheeled wagon’, normally requiring eight horses to pull it, might only need two with a Montgolfier attached. This aptly suggests how difficult it was, even for a trained scientific mind like Banks’s, to imagine the true possibilities of flight in these early days.18

Benjamin Franklin, ‘the old fox’, as Banks’s secretary Charles Blagden called him, was quick to suggest various menacing military applications, perhaps in a deliberate attempt to fix Banks’s attention. ‘Five thousand balloons capable of raising two men each’ could easily transport an effective invasion army of ten thousand marines across the Channel, in the course of a single morning. The only question, Franklin implied, was which direction would the wind be blowing from?19

His other speculations were more light-hearted. What about a ‘running Footman’? Such a man might be suspended under a small hydrogen balloon, so his body weight was reduced to ‘perhaps 8 or 10 Pounds’, and so made capable of running in a straight line in leaps and bounds ‘across Countries as fast as the Wind, and over Hedges, Ditches & even Water …’ Or there was the balloon ‘Elbow Chair’, placed in a beauty spot, and winching the picturesque spectator ‘a Mile high for a Guinea’ to see the view.

There was also Franklin’s patent balloon icebox: ‘People will keep such Globes anchored in the Air, to which by Pullies they may draw up Game to be preserved in the Cool, & Water to be frozen when Ice is wanted.’20 This contraption would surely have appealed to the twentieth-century illustrator W. Heath Robinson.

Franklin, who suffered formidably from gout, later suggested that a balloon might even be used to power a wheelchair. When he had returned from Paris to Philadelphia in autumn 1785, he began using a sedan chair lifted by four stout assistants for his daily commute from his house to the Philadelphia State Assembly Rooms. He suggested reducing the requisite manpower by 75 per cent, simply by harnessing the chair to a small hydrogen balloon, ‘sufficiently large to raise me from the ground’. This would make his malady less vexatious for all concerned, by providing a ‘most easy carriage’, lightweight and highly manoeuvrable, ‘being led by a string held by one man walking on the ground’.21 fn6

8

In 1785 Tiberius Cavallo, a Fellow of the Royal Society, put together the first British study of ballooning. His A Treatise on the History and Practice of Aerostation studiously adopted the French scientific term for ‘lighter-than-air’ flight, but moved far beyond national rivalries. He wanted to consider the phenomenon of flight from both a scientific and a philosophical point of view. He thought that ballooning held out immense possibilities, less as a transport device than as an instrument for studying the upper air and the nature of weather. This distinction between horizontal and vertical travel would have a long subsequent history.

Cavallo was a brilliant Italian physicist who had moved to London at the age of twenty-two, and had already written extensively on magnetism and electrical phenomena. Elected to the Royal Society in 1779, he quickly turned his attention to ballooning. He had some claims to be one of the first to inflate soap bubbles with hydrogen as early as 1782. Although a handsome portrait is held by the National Portrait Gallery in London, he is now largely and unjustly forgotten. Yet his study emerges as the most authoritative early treatise on the subject of ballooning in either English or French. The copy of Cavallo’s book held by the British Library is personally inscribed ‘To Sir Joseph Banks from the Author’, in severe black ink.

Cavallo carefully adopted a considered and even sceptical tone, well calculated to appeal to Banks. Much had been made of Vincenzo Lunardi’s historic first flight in Britain, in September 1784, when he flew from London to Hertfordshire with his pet cat. The newspapers of the day all declared Lunardi a heroic pioneer, a patriot and an animal lover, although the gothic novelist Horace Walpole – author of The Castle of Otranto – roundly criticised him for risking the life of the said cat. But Cavallo noted: ‘Besides the Romantic observations which might be naturally suggested by the Prospect seen from that elevated situation, and by the agreeable calm he felt after the fatigue, the anxiety, and the accomplishment of his Experiment, Mr Lunardi seems to have made no particular philosophical observation, or such as may either tend to improve the subject of aerostation, or to throw light on any operation in Nature.’23 fn7