Полная версия

England’s Lost Eden: Adventures in a Victorian Utopia

We all reinvent ourselves. We conflate memory and fact, and reinterpret the pleasure and pain of the past to suit the present and form our future. Mary Ann too was convinced of her story, and felt the need to share it – a desire only heightened by the obstacles placed in its way, not least that of her sex. Yet being born a woman was not necessarily a bar to her calling: not only were there precedents for female preachers among the Methodists and the Quakers, but her experience – the loss of her children, her lowly origins – made her message more immediate. It was said that her ‘thrilling, and often overpowering speeches had a vivid effect on sympathetic lady hearers, for she observed proprieties of behaviour, and there was nothing coarse or vulgar about her’. And like other female mystics, from Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, to Hildegard of Bingen, Teresa of Avila and Joan of Arc, she cited higher authority; like the Maid of Orleans’ armour, her visions were a defence against male prejudice. Who could doubt the Word of God, even if it came from a farm labourer’s daughter?

The world had always been reluctant to give women a voice; yet more so when their prophecies crossed the barrier between Christian and pagan, between witch and saint. In Yorkshire, Mother Shipton had seen the future from her Knaresborough cave and its dripping well, where I was taken as a boy to see strange objects dangling from a rock ledge, the pale brown mineral-rich water turning soft toys into modern fossils. Around the same time as Shipton made her predictions of telegrams and aeroplanes, the Holy Maid of Kent, Elizabeth Burton, was hanged for prophesying Henry VIII’s death. In Mary Ann’s native East Anglia, the power of magic lingered long after it had faded elsewhere. The eastern counties became home to the Family of Love, a heretical cult imported across the sea from the mirror-lowlands of Holland, which preached that heaven and hell were to be found on earth and that it was possible to recreate Eden through communal living; Ely was declared an ‘island of errors and sectaries’, and parts of this countryside were said to be heathen until the draining of the fens in the 1630s – as if the act of reclamation deprived the land of its ancient aquatic spirits.

Perhaps devils took hold instead. In 1645, Matthew Hopkins, Witchfinder General, instituted his campaign in Suffolk, when neighbour denounced neighbour and women were walked to keep them awake until their demonic familiars came to betray them. Those who miscarried or whose children were stillborn were accused of sacrificing their offspring. At Aldeburgh, seven women were hanged as witches, and the Borough paid Hopkins £2 for his work. Had she been born two centuries earlier, Mary Ann too might have been stripped and searched for the devil’s marks – although her searchers would have found Christ’s.

Two hundred years after Matthew Hopkins’ reign of terror, Mary Ann left Ipswich to travel the villages around Woodbridge and Saxmundham, the land she knew so well from her childhood and where she thought her words would be heard. As she preached in the open air at Little Glemham, it must have been odd for her young children to witness the change in their mother, leaving the family home for the fields of rural Suffolk. Mary Jane, then in her teens, would assist at the services by teaching and playing the piano, although she was soon to marry; William, however, just six years old when Mary Ann’s mission began, would find himself caught up in her cause.

The Primitive Methodists were well represented in these places, and Mary Ann was invited to preach at their chapel at Stratford St Andrew’s. But her unorthodox ideas offended them, and many of those who had listened now refused to hear her increasingly radical ideas. So Mary Ann sermonised in market squares, a soapbox orator in shirtwaist and curls. Unconfined by marriage or maternal duties, she took her message to the disenfranchised and the dispossessed – just as the first British Christians had been lowly peasants who found a new sense of community in their faith, and just as the same common people had been identified as God’s chosen ones during the religious revolutions of the seventeenth century, with its own dreams of ‘utopia and infinite liberty’ and a theocracy led by another East Anglian prophet, Oliver Cromwell. In her version of Christ’s elegantly paradoxical beatitudes, which called for the poor to be rich and the downtrodden to be free, Mary Ann promised social justice and heaven on earth. Those who had failed to find a place in the world could find a home with her, by choosing a new family. And in questioning the morality of marriage, she offered women the right to choose God over slavery; to be freed from the shackles of sexual demands and the dangerous burden of child-bearing. Mary Ann had issued a challenge to the nineteenth-century family, even as she sundered her own: it seemed she really was set to turn the world upside down.

Girlingism, as it became known, embraced those over whom industrialisation had ridden rough-shod. It offered an alternative way of life almost revolutionary in its aims, although its communist ideas were rooted in Scripture. Consciously or not, Mary Ann appeared to be influenced by sects such as the Family of Love and the Diggers and the Ranters of the Interregnum who took the Acts of the Apostles – ‘And all who believe were together and had all things in common’ – as precedent for their communality. In 1649, the Diggers had staked out their allotments on St George’s Hill in Surrey, and although their attempt at Eden, seeing the Second Coming as an earthly return to paradise, lasted little more than a year, the visionary William Everard, whose followers spoke with angels, went on to found other rural Digger communes. These provided patterns for what Mary Ann would attempt. And while she would admit a spiritual kinship with the early Quakers – more extreme in their early expression than in their later quietude – there was another echo to be detected, in the newly emancipated Catholic Church. In 1858, as Christ appeared in Mary Ann’s Ipswich bedroom, another young peasant girl saw the Virgin Mary in a French cave, as if her solemn, beautiful statue had come to life, her robe as blue as the sky from which she had fallen in augury of her Son’s return. Bernadette knelt on the ground and seemed to eat the earth: to some, a symptom of psychological disturbance; to others, an indication of the passion of her visions. In an increasingly secular century, it was no coincidence that the visitations at Lourdes and the agitations of the Girlingites registered simultaneously on the spiritual scale.

Back in Suffolk, Mary Ann’s mission had a direct and intensely personal effect on another young woman. Eliza Folkard, a carpenter’s daughter from Parham, sang in the Methodist choir, but one day she attended a Girlingite meeting and suddenly got up and began to dance. She then spoke for an hour, describing ‘how she had been convinced of sin at the age of 17, but did not give her heart to God until after a long illness’. In a further reflection of Mary Ann’s conversion, she declared that Mrs Girling was truly the herald of the Second Coming, and as she emerged from her trance she embraced her new mother. To others, however, Eliza’s closeness to Mary Ann would lead to the notion that she was in fact her daughter, and perhaps an indication of sin. And where Mary Ann was dark, Eliza had blonde hair, a race memory of Viking invaders: she would become the pulchritudinous face of Girlingism, the angelic obverse to Mary Ann’s darker power.

Eliza’s conversion was followed by that of Henry, or Harry Osborne, described as a ‘rough, uncouth and illiterate farm-labourer, of pugilistic tendencies’ – a useful person when danger threatened. In fact, Harry was a thirty-one-year-old widower and shoemaker; but in this gallery of types, he became Mary Ann’s right-hand man, completing the trinity that she presented to the world – and introducing new rumours about their own relationship.

Within eighteen months Girlingism had fifty adherents, for whom it was compulsory to receive ‘the Spirit, or the baptism of the New Life’ and to practise celibacy, without which they could not be accepted by the Saviour on His return, ‘which was expected to be sudden as the lightning’s flash’. Anyone joining the group had to give up all their worldly goods; from there on ‘the old ties of husband, wife and lover were to be lost in a fraternal bond’; they were now all brothers and sisters, living ‘a pure and holy life’. Mary Ann was known as Sister: her sororial title was levelling and egalitarian, but it also gave her a sense of pre-ordained mission. As a universal relative, she cast off her wedded status and assumed a new role, that of a secular nun or religious nurse.

This was neither an unusual self-discovery, nor a disreputable one: the most famous sister of the age, the high-born Florence Nightingale, had recently entered imperial iconography as the Lady with the Lamp, inspired by her own three visions of Christ; while the empire itself was ruled over by a matriarch queen from her seaside home on the Isle of Wight. But it was also the coming era of the New Woman, and Mary Ann would be seen as part of these powerful moves towards a new female identity: ‘She stands forth, in this age of “woman’s mission”, fearlessly to lead and encourage a pure society based upon the inward law of her nature’, claimed one new age magazine; although a more hostile account saw her as ‘a curious growth of the “Women’s Right” genus, from a theological point of view; and when she stretches her bony arms, in all the warmth of native eloquence, she reminds one of a pious scarecrow tossed in the winds of fanaticism and superstition and set up as a terror to evil doers in the way of religious enthusiasm.’

A woman’s power was still to be feared; and like those new women, this universal sister’s tenets, intended to create an alternative clan, were not entirely welcome as they sundered families and married couples and separated children from parents. When a later visitor asked Mary Ann, ‘Why not procreate?’, she replied that the earth was already too full. Such sentiments echoed those of Reverend Malthus, who believed mankind was doomed if it continued to reproduce without check. But they also threatened the defining unit of an age which relied on reproduction. The family yoked the workers of the industrial revolution to the demands of capitalism; Mary Ann directly opposed that economic adhesion. For such a person of such a background and of such a sex to set up such a challenge was unacceptable. Mrs Girling made a travesty of her married name, and in the process became an anti-woman.

There were other reasons to fear Girlingism: it created tensions not just between families, but between communities. In an era of insecurity and high unemployment – exemplified by the agricultural strikes which hit East Suffolk in the early 1870s as the newly formed Agricultural Labourers’ Union clashed with the Farmers’ Association – men lost their jobs because of Mary Ann. In the market and barrack town of Woodbridge, her teachings began to concern clergy and upset landowners, anxious at her effect on their flocks and labour force: ‘Many of the males were discharged from their situations, and others suffered loss in a variety of ways’. To some it seemed they had lost their senses to religious mania, and were suitable subjects for the local lunatic asylum at Melton – an establishment of more than four hundred disturbed souls, their occupations, listed next to their initials in the 1871 census, representative of Mary Ann’s constituency: farm labourers and their wives; factory girls and seamen’s wives; soldiers and needlewomen; chimney sweeps and policemen’s wives; brush makers and lime burners; or simply, in the case of ‘V. F.’, a ‘loose character’.

They were the psychiatric casualties of an industrial era, the kind of minds susceptible to a woman who might have found herself similarly incarcerated. Or perhaps Mary Ann evoked an older belief, when people had laid votive offerings in the lakes and rivers, reaching down to that elemental world beneath their feet. Whatever the source of her power, it seemed there was a primal force gathering around this prophetess, one which would invoke spirits and provoke opposition. One man bet his friends that he would shoot Mary Ann on a certain night – although in the event the would-be assassin himself converted and became a Girlingite, a miracle taken by her followers as proof that their leader was protected by God. That which did not kill her made Mary Ann stronger, and in this sensational narrative – something between penny dreadful and missionary tract – she had become a symbolic, almost revolutionary figure.

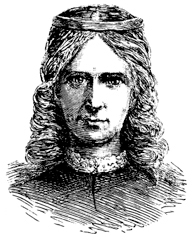

A later image of Mary Ann depicts her as an androgynous angel from some Renaissance woodcut, wearing indeterminate, anachronistic dress, her head encircled by a band in simple recognition of her sacred mission. Her stare challenges the viewer and imbues the portrait with the air of an icon. This idealised Mary Ann is far from what we know of her true features; more Joan of Arc as seen in a Victorian picturebook than the face of a farm labourer’s daughter. But equally, it could be an advertisement for the latest nostrum, lacking only the caption, Mother Girling Saves.

Girlingite meetings took a set form. Bible verses were read and debated, followed by prayer. But then came the strange dancing and trance-like speaking in tongues which Eliza Folkard had exhibited, and which were already attracting crowds. These shaking fits earned the sect the nickname Convulsionists, although they preferred to call themselves Children of God, from St John’s gospel, ‘… to all those who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God; who were born, not of blood nor of the will of flesh nor of the will of man, but of God’. Like the Corinthians in the wake of St Paul’s mission, they would ‘jabber and quake’ when in the spirit, led by Mary Ann herself, leaping from foot to foot while waving her arms as if beckoning while she exhorted the Lord’s name. To some these antics resembled the dance of a savage; others watching the ‘springy, elastic movements and considerable waving of her arms … could hardly resist the comic aspect of the scene’.

Soon enough these rites attracted the attention of the press, and on 20 April 1871 a headline appeared in the Woodbridge Reporter & Aldeburgh Times:

MOBBING A FEMALE PREACHER.

The accompanying story may have been the first occasion on which Mary Ann’s name appeared in print; it was certainly not the last.

Reporting on a case heard at the Framlingham Petty Sessions by F. S. Corrance, the local Member of Parliament, and two clergymen – the Reverends G. F. Pooley and G. H. Porter – the newspaper gave details of five young men, William Goldsmith, James George, Samuel Crane, James Nichols and John Barham, who were charged by a farmer with ‘riotous behaviour in his dwelling, which is registered as a place for religious worship’.

At first it seemed a matter of mere youthful high spirits. The farmer, forty-eight-year-old Leonard Benham of Stratford St Andrew, worked 138 acres – belonging to the Earl of Guildford – where he employed three men and a boy, as well as two household servants (one of them being twenty-year-old William Folkard, a kinsman of Eliza’s). But Benham was also a member of the Children of God, and had resolved to support Mary Ann ‘at any cost’. He would pledge his entire family – his wife Martha, forty; his daughters Ellen, twenty, Emma, thirteen, and Mary Ann, then four years old; together with his sons Arthur, then aged sixteen, William, fifteen, and George, just five – to the cause.

That Sunday afternoon, a meeting had been held in Benham’s house which was attended by the five defendants – not by invitation. As the Girlingites prayed, one of the young men, John Barham, began to talk and laugh. When asked to be quiet, he replied by singing and hallooing, with his friends joining in.

‘I went to the door and stood near them,’ Leonard Benham told the court. ‘They said, “Take your sins off your own back, we won’t believe you, you’re a liar.” I told them mine was a registered house. They told me not to daubt them up with untempered mortar’ – an obscure metaphor which would pursue the Girlingites, along with mobs hurling slack, or slaked lime.

The hooligans then began pulling off his wallpaper, and declared that ‘they would be d—if they wouldn’t kiss Mrs Girling before they left’. Failing in this, they tried to kiss another member of the congregation, Robert Spall. ‘Not being able to do that, they said they would kiss Mrs Spall, but did not attempt to do it.’

That night the gang came back to finish what they’d started. ‘What a pity it is you young men come here and make a disturbance,’ Benham told them. ‘The law is very stringent about this, and you’ll hear something from me about it.’ But Nichols strode into the room and began shouting and stamping, while Goldsmith mockingly held up a stick to which he’d attached a red handkerchief, saying, ‘This is a flag of distress.’ He then began to declaim a text of his own, and sat down to light his pipe. Crane, also smoking, cried, ‘Pinpatches and sprats at three pence a quarter.’ The scene turned violent as the gang began to break up the furniture, with Barham sitting on the window-sill shouting, ‘My wife has run away with a man that has three children, and when she comes back I’ll be d—if I have her again.’

The mob had tailored their insults to the Girlingites, and their actions had the air of a concerted assault rather than the casual vandalism of bored young men with nothing better to do on a Sunday night in a small country village. The explanation became clear when Benham told the court that such meetings were held every three weeks at his house.

‘We have two or three places where we worship under the head of Mrs Girling. Singing hymns is part of the services, which were usually well attended. I have never seen anyone on the floor fainting. Mrs Girling has a husband and two children at Ipswich. The rooms will hold one hundred people.’

Mr Jewesson, acting for the defence, asked, ‘You’re one of the disciples, ain’t you?’, his biblical overtones somewhat undermined by his grammar.

‘Yes, and thank God for it,’ replied Benham, who proceeded to give intriguing details of the sect and the power of their leader. ‘There is silence generally when Mrs Girling reads the word of God … It is customary for any person to pray who likes. I never saw two or three praying at once – one stopped till another had finished. Mrs Girling was the only one that read and expounded.’ He admitted, modestly, ‘I am not sufficiently high to read and expound the Word of God; I wish I was.’

It wasn’t clear whether he was referring to his stature or his spiritual status. Mary Ann had first come to his house eighteen months ago – ‘Eliza Folkard sometimes expounded, but not publicly’ – and although he had never seen anyone faint at any of these services, ‘I have seen them fall under the power of God.’ As an elder of the Children of God, Benham sought to counter some of the more extraordinary rumours already gathering around them. He told the court that their services differed little from those of other dissenting chapels:

‘It is just the same with the exception that other people give out a text while Mrs Girling only expounds the word of God.’

Yet there was the sense of something other at work, not least in the shape of Mary Ann herself and the transcendence to which she aspired.

‘By our people I mean the people who follow Mrs Girling. We subscribe money amongst ourselves. We only provide Mrs Girling with clothes and boots. We pay nothing for the rooms; I give mine gratis.’

‘You speak of falling down,’ remarked Mr Corrance, ‘when does that occur?’

‘Very often, sir,’ replied Benham. ‘We see people fall down by the power of God.’

‘What do you mean by that?’ asked Corrance.

‘They go into a trance, sir, and can see all things that are going on around them. We allow them to remain till they come to themselves.’ Benham insisted that they never disturbed anyone: ‘We have never recognised these roughs as part of our congregation … They are the Devil’s congregation, and ours are the children of God.’

This testimony was supported by key figures in the movement: Alfred Folkard, Eliza’s father; Cornelius Chase, a twenty-seven-year-old coachmaker, and Isaac Batho, postmaster and shoemaker, both of Benhall; and Sally Spall, wife of Robert, a machinist from Hascheston, with whom Mary Ann had been staying during her missionary work. Sally Spall bore witness to the ‘kiss of charity’ which had prompted the gang’s sarcastic amorousness.

‘It is usual to kiss each other indiscriminately?’ Mr Jewesson asked Mrs Spall.

‘Yes, sir,’ she replied.

‘Both males and females?’ inquired Mr Corrance.

‘Both, sir.’

‘Men, women and children, I suppose?’ prompted Jewesson.

‘Yes, sir.’

This sounded decidedly immoral, so Mr Hill stepped in, acting on behalf of the Girlingites: ‘I suppose it was only a brotherly and sisterly expression of affection?’

‘That’s all,’ said Mrs Spall.

‘You don’t rush into just anyone’s arms – it is only the members of the congregation?’

‘It’s a salutation, I suppose,’ remarked the Reverend Pooley.

‘Just so, sir,’ said Mr Hill.

Mary Ann was as much on trial here as any of her potential assailants. ‘The members of this sect were led by a woman,’ Jewesson was reported as saying, ‘of whom, without imputing anything wrong to her, he might say that it was to be regretted she should leave her husband and children, and put herself forward in the way she did, creating as she must necessarily do so, a disturbance wherever she went.’ Thus Mary Ann was portrayed as a troublemaker, a woman who, by her very sex, sought to disturb the status quo. Jewesson went on to claim that his clients had gone to the service as potential converts, ‘and the confusion which took place was not caused by them or anyone connected with them’. It was a lame excuse. Hill said his client was willing to drop the charges if his expenses – and the fine – were paid there and then; and in an extraordinary intervention which to some seemed to compromise the impartiality of the Bench, Mr Corrance himself advanced the required sum for the defendants.

A legal resolution had been reached, but the wider question of the Girlingites and their freedom to worship remained. The Woodbridge Reporter may have been a local paper, but it reported on national issues: ‘the Rights of Women’; ‘Spirit Rapping Extraordinary in Woodbridge’ (which turned out to be a skit advertising alcohol); Primitive Methodism; the vaccination debate; and emigration, ‘a subject uppermost in men’s minds now’. Disturbing events across the Channel – the ‘Literary, Scientific, and Artistic Communists’ in the Paris Commune – sat alongside reports of riots in Dublin and an apocalyptic editorial on cholera, ‘the most destructive of human diseases’, whose invasion no ‘“streak of silver sea”’ could prevent. Amid such signs and wonders – as if plague and famine might yet sweep the land, just as the sea could break its defences – the appearance of a local prophetess was of more than a little interest; especially when her crusade provoked a riot at the Mechanics’ Institute in Woodbridge.

Mechanics’ institutes were established in the 1820s as educational centres for artisans. Often used for lectures on sectarian beliefs and spiritualism, they provided the working man with ‘an opportunity to ride the wave of the new pseudo-sciences’. On 2 May 1871, the Reporter noted that ‘some printed handbills circulated in the town announced that Mrs Girling would preach the Gospel in the Lecture Hall, on Tuesday evening, at half-past seven’. Such advance publicity ensured that the hall was packed, with a crowd of one hundred clamouring for admission, and ‘a great number who went were not prompted with the desire of hearing the Gospel preached …’ Mr Joseph Cullingford attempted to address the crowd, ‘but was frequently interrupted. Mrs Girling stood on the centre of the platform, and by her side was … a Miss Folkard from Parham.’ While many were still trying to get in – some by forcing the door – others were trying to get out, overcome by the heat and noise inside. It was the first indication of a mass reaction to the Girlingite gospel: a frightening spectacle to some; to others, rather farcical. Mr Cullingford tried to leave the hall, but as he did so the door was suddenly locked, leaving his coat tails trapped and the unfortunate man ‘subject to the rude remarks of the roughs for some time’ while he banged on the door unheard, such was the furore within.