Полная версия

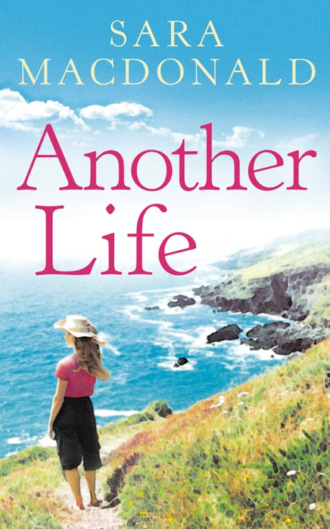

Another Life: Escape to Cornwall with this gripping, emotional, page-turning read

John Bradbury, with his back to the councillor, gave Gabby a wink of encouragement.

‘Gabrielle, come and meet everybody. You know Peter Fletcher from Truro Museum. Tristan Brown is from the Western Morning News. Councillor Rowe, I think you’ve met before. And this is Professor Mark Hannah, from Montreal. Mark has been entirely responsible for the safe return of our beautiful figurehead to St Piran. Mark, this is Gabrielle Ellis, our local restorer.’

Gabrielle looked up into the amused eyes of the Canadian. He held out his hand.

‘Great to meet you, Gabriella.’ His hand was warm, the fingers long and thin, his grip firm. Suddenly self-conscious, Gabby looked away, smiled at Peter Fletcher, and then they all turned and walked towards a corner of the museum where the figurehead lay on her back on a worktable, swathes of bubble wrap still around and underneath her like an eiderdown.

Gabby stared down at the wooden figure, held her breath. Lady Isabella was so much more beautiful than she had imagined. She moved closer and looked at the high cheekbones, the sightless eyes, the scarred face and neck. The wood was dry with small cracks, the paint flaked, remnants of colour caught in the corner of her eyes like tears.

The face was extraordinary, so meticulously carved that it seemed to have an expression of combined sensuality and haunting sadness. This face, Gabby thought, had been carved with a doomed or careless passion.

The Canadian, watching her, said softly, ‘Meet Lady Isabella.’

Gabrielle was unable to keep the thrill out of her voice; ‘She is exquisite.’

Mark Hannah laughed. ‘She is, isn’t she.’

‘Where on earth did you find her?’ Gabby asked.

‘Pure chance. I was in Newfoundland giving a series of lectures at the Marine Institute of Memorial University. I had a couple of days there and I decided to go walking. I suddenly spotted her in a garden in Bonavista Bay, among the usual flotsam brought up from the sea. She was wedged between two trees.

‘I knocked on the door and the man who lived there told me she had been given to him as part of a debt owed by his brother-in-law who had once lived in Malpeque Bay, Prince Edward Island. He thought she had been exhibited at some time, maybe at the Green Park Shipbuilding Museum on the west side of Malpeque Bay. I could see a crude attempt to restore her had been made but she was beginning to deteriorate and I asked if he would be willing to sell her to me.’

The boy from the Western Morning News was scribbling fast into his notebook.

‘After a lot of haggling I bought her for the sum of the whole debt owed to him. I told myself I wanted her because I thought she would make an excellent research project for some of my students, but it was love at first sight. I had to have her.’

Gabby, watching him, thought, He must have told this story many times and yet the excitement of the discovery is still with him.

‘I wonder how long she was exposed to the elements,’ she said, looking at the wood-rot and damage at her base.

‘The man told me he had kept her in his old boat shed and had only put her in his garden when he needed his shed.’

Peter Fletcher touched Gabby’s arm. ‘Thanks to Mark’s detective work I was able to trace the original plans for the schooner Lady Isabella. They were in the marine archives in Devon. She was a two-masted ship, commissioned by a wealthy master mariner, an ex-naval gentleman called Sir Richard Magor whose family were big in shipbuilding here in Cornwall and Devon, as well as Prince Edward Island.’

Gabby felt a surge of excitement. ‘Do you have the name of the man who carved the figurehead?’

Peter grinned at her. ‘Oh yes. His name was Tom Welland. He was quite a famous woodcarver in his day. His figures were unmistakable.’

Gabby turned back to the figurehead. She longed to touch that frail face, but knew she must not. The Canadian came to stand beside her.

‘Tom Welland went in for detail. Not all figurehead carvers did, many were quite primitive. He became well-known, not just in England but on the continent as well as Canada and America. He was an artist and was able to pick and choose his commissions. He appears to have travelled widely when he was young, probably as crew on the trading vessels, because traces of his work can still be found in Mediterranean ports. Then he just seems to have stopped carving. No one knows what happened to him. John tells me his family lived and worked around St Piran all their lives.’

‘They did indeed,’ John Bradbury said. ‘Most of them are buried here, but not Tom.’

‘It’s wonderful to have a date. It means we know exactly when she was carved and what materials they would have used,’ Gabby said.

‘But how did you connect her to Cornwall?’ Tristan from the Western Morning News asked Mark Hannah.

The Canadian smiled at the boy. ‘I knew she must be European, possibly British from a trade schooner. The nearest we have to your schooners or barques are Boston trawlers, and the figureheads differ. I went to the public archives. Prince Edward Island was once a British colony and there had been a thriving shipbuilding business between the island and the West Country in the nineteenth century.

‘I couldn’t find any sign of a trading ship called Lady Isabella registered as being built on the island, but records get destroyed or go missing and when I turned to the register of wrecks it jumped out at me. A schooner, the Lady Isabella, lost in a storm in 1867 off Bonavista Bay. Instinct told me this was her. There was no mention of the schooner carrying a figurehead, so I asked an English colleague to check for me in the Lloyds List, London, and there she was, listed and described with figurehead alongside the date of her sinking.’

Peter Fletcher took up the story again. ‘Thanks to Mark’s detective work we looked at the most probable Cornish owners and builders of that period. I went to the Public Record Office to look down the Lloyds Register. Trading vessels had to be registered to get an insurance certificate.

‘I found that a schooner called Lady Isabella, built in Prince Edward Island in 1863 had been granted an A1 certificate of seaworthiness by Lloyds London in 1864. Then I went to the Guildhall Library, where Mark’s colleague had already looked, to double-check the Lloyds List. This also stated that Lady Isabella was wrecked off Newfoundland with all hands in 1867. By that time she was owned by a Daniel Vyvyan, but it was common for ships to be sold on when tonnage was profitable.’

‘So,’ Gabby asked, ‘was this Isabella, Sir Richard Magor’s wife?’

John Bradbury said, ‘We don’t know, bit of a mystery there. Peter and I have been going through the old parish records. The Magors were not from the parish of St Piran, they were an old Falmouth seafaring family and many of them were master mariners. Sir Richard lived in Botallick House, now owned by the National Trust in the parish of Mylor. In the Mylor parish register there is no record of him marrying in the 1860s. None at all.’

‘What about this Daniel Vyvyan guy, who owned her when she sank?’ Tristan asked.

‘The Vyvyan family have lived in St Piran for generations. They owned the mausoleum-like house you see on your right as you come into St Piran. It was Perannose Manor and is now a Christian conference centre. Daniel had two wives, a Helena Vyvyan, née Viscaria, and a Charlotte, née Flemming; both are buried with Vyvyan in the family crypt.’

‘What about daughters?’ Gabby asked.

‘Ah, I was coming to that. Helena and Daniel had a daughter Isabella in 1846 …’

‘What?’ Everybody looked at John Bradbury.

He laughed. ‘I have more! I was talking to a long-retired vicar of Mylor, a bit of an amateur historian and sleuth. He maintains there was an Isabella who was the first wife of Sir Richard Magor. No one knows what happened to her, she is not buried in Mylor or here in St Piran. Legend has it that a page in the parish records registering a marriage in 1864, containing that of Magor and Isabella Vyvyan was torn out, destroyed shortly after that marriage …’

‘Maybe that’s why Richard Magor sold the ship to Isabella’s father, if she had fallen out of favour,’ Gabby said.

‘Quite possibly,’ Peter said. ‘And of course our research is ongoing. What we do know is that in the years the Lady Isabella was built, St Piran had a thriving boat-building business employing many men in the area.’

‘This is all very interesting indeed,’ Councillor Rowe said, ‘but the business of the morning is who is going to restore the figurehead now she is here. The rest we can look forward to hearing later.’

They all stared at him. How on earth could he not be interested in a piece of history that he was hoping to raise money for, Gabby wondered.

‘Quite right!’ Mark Hannah looked as if he was having trouble not laughing. ‘The business of the day.’

They turned back to the figurehead. Mark Hannah said to Gabby, ‘One of the reasons Tom Welland became so well-known and sought after was that sailors believed his carvings were blessed because his faces always looked so alive.’

‘It’s true,’ Gabby said. ‘Her face is disturbingly alive. It’s the eyes, I think.’

‘Mark has offered to go on researching the history of the Lady Isabella for us in London, when he has time between his lecturing engagements and writing his book, and we’re very grateful. Of course, we will go on delving this end too, and hopefully we will discover more about the schooner. We do have a great deal to thank you for, Mark,’ Peter said.

‘Indeed we do,’ John Bradbury agreed, looking pointedly at Councillor Rowe.

Councillor Rowe cleared his throat. ‘London is where I think this valuable piece of local history should be restored. We need a London expert. It is only right and proper that we have the best we can afford.’

Gabrielle knew she was being rebuffed and the councillor wanted to ease her out, but she was not going to give him the satisfaction of seeing that she suddenly felt unsure of her credibility; for it was true, she had never restored a figurehead. She felt the Canadian’s eyes on her, but when she looked up she knew instantly he was rooting for her.

He said in his soft drawl, turning to Rowe, ‘I’ve heard excellent accounts and seen for myself some of Gabrielle’s work. Peter took me to the church of Saint Hilary to see the panels and the two painted wood sculptures Gabriella restored. I also drove to Lanreath to see the painted medieval oak rood-screens she worked on. I can see no good reason for this figurehead being lugged to London if it can be restored professionally here. What do you think, Peter?’

‘I have no doubt whatsoever that Gabrielle is more than qualified to do the job. I’ve worked closely with her before and I’m sure she will do it justice. She’s been working with Nell Appleby, who is one of the best fine art conservators in the county.’

He turned to the councillor. ‘I’m sure you must remember the two major sculptures that Nell and Gabrielle restored about two years ago, Rowe? The seventeenth-century Spanish gilded wood carving of Saint Joseph; and the one of Saint Ann, probably fourteenth-century? It was Gabrielle who found the fragments of original paint.’

Gabby turned away from the men to the wistful wooden face, to the shaved and battered bodice, to the carved fingers with the arms held down close to her body so she could fly through the water.

‘I know you will need to do a proper inspection, Gabrielle, but is it possible to give us a quick assessment?’ she heard Peter ask behind her.

Gabby got out her magnifying glasses and knelt beside the figurehead, bending close, careful not to touch any of the painted sections. She talked the group of men through the various methods she would use, the tests she would carry out before she started. As she talked and examined the face, the cheekbones looked suddenly warm and smooth, and as Gabby’s fingers hovered over her face a strange feeling of familiarity flooded through her as if she was bending to the face of someone she knew well. She wished Nell had come, the detail was breathtaking.

‘The work in this …’ Gabby marvelled as she examined an eyelid, the relaxed and languid lips, ‘… is such a labour of love. She must have seemed so alive and vivid in her once blue dress with the water rushing past her.’

The Canadian’s expression was intent, as if he needed to gauge Gabby’s feelings and the care she would take with his beloved figurehead.

Peter Fletcher smiled. ‘It is the most wonderful find. Gabrielle, would you be willing to take her on?’

Gabby looked up, was about to answer, Yes, oh yes, when Rowe said, ‘However proficient Mrs Ellis is, a figurehead is quite a different matter to a sculpture or painting. This has been immersed in salt water for many years and has been half-ruined with modern paints. I believe we decided to discuss the restoration carefully before we offered it to anyone …’

‘That is exactly what we are doing, discussing it,’ the vicar said crossly, cutting him off. ‘That is why we have two experts in front of us who know what they are talking about …’

‘There is a question of cost,’ Rowe said, interrupting in his turn.

Gabby looked at the vicar. ‘I can’t estimate the time it will take off the top of my head. But of course I would come and do a proper detailed inspection before I sent you a quote.’

Peter was also getting annoyed with Rowe. ‘I can tell you now, the cost of the figurehead being restored and insured outside the county is going to be far more than any quote from Gabrielle. You are quite wrong; it is not a different skill. A figurehead is like a panel and Gabrielle is expert at wood treatments and polychrome. Which in lay terms, Rowe, are painted surfaces. She also has knowledge of pigments from medieval to contemporary paints. We have an expert on site, so I am unsure what your reservations are.’

Gabby felt like whispering, I’ll do it for nothing, just let me have the chance, but she knew it wasn’t professional and Nell and Charlie would explode.

Rowe opened his mouth to argue and the Canadian said evenly, ‘I suggest that having got the figurehead safely home to Cornwall, not without some difficulty, it would be foolish to move her again. She is damaged and had I thought she would not be restored locally, I would have left her in London.’

There was an uncomfortable silence. Rowe was an unpopular councillor but he was good at obtaining money from various sources. The Canadian winked at Gabrielle then watched the councillor with veiled amusement.

‘I think,’ the vicar said, ‘we should all repair to the pub and discuss this over lunch.’

‘Good idea,’ Peter Fletcher said.

‘Indeed,’ Rowe said. ‘I can then go on to talk to the Heritage people. Well, Mrs Ellis, thank you for coming, we will inform you of our decision.’

‘I meant,’ the vicar said coldly, ‘for Gabrielle to accompany us and be part of the discussion.’

Peter took Gabrielle’s arm as they walked out of the church. He was a polite bachelor and he deplored Rowe’s crassness. ‘Let’s go and see if we can find a table.’

Gabrielle smiled at him. ‘Peter, really, it’s fine. I should be getting back anyway.’

They all emerged into the harsh sunlight. Gabby put on her sunglasses with relief.

Peter said, ‘I think it’s important that you stay, Gabby. We are keen that you do this restoration, that’s why we rang you, and I’d like to talk this through with you.’

‘I agree,’ the Canadian said, falling into step the other side of her. ‘It would be good to talk with you, if you have the time. That figurehead has been my baby for quite a while.’

‘Settled,’ the vicar said. ‘Come on, Gabrielle, off we go.’

Peter moved away to talk to him and Gabby was left with the Canadian. She felt suddenly, infuriatingly tongue-tied. From the moment she entered the church she had been aware of his eyes constantly on her face.

He was a tall and lean man, and in the sunlight she saw he was older than she had first thought. His eyes crinkled with amusement as he bent to her.

‘Now what the hell could you have possibly done to upset that asshole?’

Startled, Gabby snorted with laughter. ‘Not me! Nell, my mother-in-law. She upset his brother, an untrained restorer, who ruined a valuable painting belonging to an old friend of hers and then charged her the earth. Nell wrote an article in the local paper. She didn’t name him but everyone knew exactly who she was talking about. It was the end of his career. Councillor Rowe has never forgiven her.’

They sat inside in the cool and Rowe pointedly ordered himself a pasty and orange juice and left. As the door closed behind him everyone relaxed. The young reporter started to quiz Mark on the details of shipping the Lady Isabella back to England while John Bradbury ordered sandwiches.

‘How’s Nell?’ Peter asked Gabby. ‘Still working, I hope.’

‘Oh yes. Nell will never really give up. She’s working on a huge painting at the moment.’

‘I met a guy in London who knew your mother-in-law,’ Mark said suddenly. ‘She’s still very highly thought of. I understand she worked for the National Portrait Gallery and then gave it all up to become a farmer’s wife.’

‘I don’t think she’s ever really stopped restoring. She just took on work locally instead of from London, when Charlie was old enough to help around the farm.’

‘Your husband?’

‘Yes.’

‘Are you Cornish?’

‘No. Charlie is.’

Now, why did she not want to talk about Charlie, as if it might make her less interesting to the Canadian?

‘They have the most beautiful farm,’ Peter said, ‘miles from anywhere and hell to find.’

The Canadian – Mark, for heaven’s sake, he has a name – was still firmly concentrating on her rather than the reporter. Gabby, who hated the focus of attention being on her, turned the conversation back to the figurehead to the relief of the earnest young man.

Back in the church car park they said their goodbyes. The two men thanked her for coming. The young reporter got on his motorbike and roared off. John Bradbury walked home to his vicarage. Peter sent his love to Nell and went to unlock his car and open all the windows.

The Canadian took Gabby’s hand and looked down on her in the amused way he had, as if laughter was never far away. She wondered if he found them all very quaint and British and tried to draw her hand away, feeling suddenly cross with him for staring, for making her tongue-tied, when she would think later of all the questions she wanted to ask him. He hung on to her hand, still smiling down at her.

‘Please could I have my hand back?’ she asked.

‘Of course you can,’ he said. ‘I’m only borrowing it – for now. It’s a very nice hand indeed.’

He let it go. ‘It’s been great meeting you, Gabriella. I’m so happy Lady Isabella is going to be in your hands. She will be, you know.’

‘I would really love to restore her,’ Gabby said, hot all over. ‘Goodbye.’

She climbed into her car and banged the door shut, deeply grateful to her sunglasses that she hoped were hiding her face.

‘Goodbye, Gabriella, take care,’ Mark said through the window and turned and walked back to Peter, who waved at her as she drove quickly past, eager to get round the corner and back onto the road home.

The sun was beginning to fade and the shadows over the fields lengthen. Cows were making their way down a field to be milked. She wondered how long Charlie could keep his herd and how diminished the farm would be without the sight of them in the yard every morning and evening. Wistfulness for everything to stay exactly as it was overtook her so suddenly that tears sprang to her eyes. She made the little car go faster, as if the farm might have disappeared altogether in the time it took her to drive home.

Chapter 4

Nell watched as the girl and the small boy crossed the edge of the daffodil field down towards the coastal path. The morning was still, the wind from the south-west soft and teasing. The sky and sea merged in the distance, blue on blue.

The day was held, breathless and hovering, like the kestrel poised, wings fluttering, over the hedge of the field where the girl walked.

It was one of those days that was too still, the lack of wind unnerving, making the morning seem as if it had drawn in on itself, gathering and collecting in a silence that should be listened to.

Nell stood, shading her eyes, holding the bowl full of corn, staring out towards the small figure of the girl in the distance. There was no hint of cloud, just the endless shimmering ocean meeting the lush green of the fields dotted with buds of emerging daffodils.

She could hear the tractor now, moving along the farm track. As it came into sight above the hedge the girl stopped and lifted the child, and he called out, waved vigorously with his small, fat hands. The driver stopped and jumped out and walked to the field gate that lay between them. The child let go of his mother and ran along the stony edge of yellow daffodils so fast he fell, and the man leapt over the gate and scooped him up, threw him up over his head. Nell could hear the child’s laughter blowing over to her like dandelion fluff on the fragile stillness of the day.

Maybe it was going to work, Nell thought, against all the odds. Watching from a distance they looked like a little textbook family; content, happy in their skins. Charlie had a son. He had never doubted for a moment that his firstborn would be a son. That had made everything easier.

The man ruffled the girl’s dark hair lightly and they stood talking for a moment before he lifted the child up onto his shoulders, walked away and climbed over the gate and placed the child in front of him on the tractor. The engine started up again and they continued down the lane, towards where Nell stood in the yard holding the bowl of corn for the hens, watching.

Silently the kestrel dived, steep and sharp. Nell could hear the sudden squeal of the baby rabbit as it was caught and pulled out of the hedge. The girl turned, startled, and clapped her hand over her mouth in horror.

‘No. No. No,’ Nell heard faintly on the wind. Then the girl made little runs up and down, crying and shouting in impotent anger at the kestrel, which lifted its prey swiftly upwards over the hedge and away in low flight.

The girl was left small and alone in the vast rolling greenness of the field. Some nebulous, disturbing feeling caught at Nell as the girl, shading her eyes, watched the kestrel until it was a pinprick in the sky.

Nell had rarely seen any show of emotion in this girl. Placid, cheerful, so careful to fit into country life, to be accommodating, to be loved. Nell realized in that brief moment that her daughter-in-law had been smothering any spontaneous expression of anger, joy or misery. She suddenly perceived Gabby as a sleepwalker in her own life. It was safer to sleep sometimes than to question how or why we came to be in a particular place at a particular time with a particular person. Nell knew this protective passivity only too well.

She turned away from the figure making its way back towards her, a small, clear silhouette against the horizon of sea and sky. She clucked at the hens and scattered the corn in a wide arc as she identified this intangible feeling of unrest. What happened when Gabrielle woke up? No one could sleep for an entire lifetime.

Nell turned Josh’s postcard over and looked at the soldier on horseback. How quickly the years had slid away. Hard to think of that little curly-haired boy in uniform. Hard to watch the green field he loved so much with its annual rash of mushrooms, disappearing into piles of earth, forming trenches for foundations that would house another generation on land she knew like the back of her hand.