Полная версия

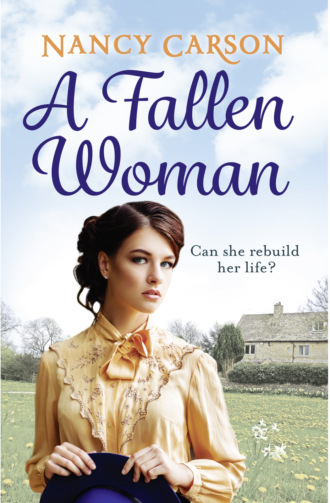

A Fallen Woman

A Fallen Woman

Nancy Carson

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins 2018

Copyright © Nancy Carson 2018

Cover design © Debbie Clement Design 2018

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

Nancy Carson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © February 2018 ISBN: 9780008134884

Version: 2017-01-09

‘There are in nature neither rewards nor punishments – there are only consequences.’

Robert Green Ingersoll

1833–1899

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

About the Author

By the Same Author:

Keep Reading…

About the Publisher

For the people of the Black Country, past and

present, who have always inspired me with their

warmth, their humour, their can-do positivity, and

their collective achievements.

Chapter 1

1892

Aurelia Sampson awoke early. The dream she reluctantly left behind had been delicious, yet disturbing. It had been about him. She had met him clandestinely, as she had in wakefulness. Adulterously, she had shared a strange bed with him that over time would become familiar – in a room lit only by a flickering coal fire, in a second-rate hotel – exactly as she had in wakefulness. The astonishing realism of the dream provided a sense of contentment and she had not wanted it to end, but when she awoke, the cruelty of truth brutally shattered that transient happiness.

With her slender fingers she rubbed tears that welled unbidden in her eyes, allowing herself both the luxury and the heartbreak of thinking about him for a few more precious moments. She stretched languidly before slipping out of bed. As she stood up and eased her feet into her dainty slippers, she shook out her long dark hair, running her fingers through its sleep-entangled strands. She moved to one of the windows, parted the curtains and opened the sash. The warm summer breeze seemed to whisper secrets through the elm trees, which cast crisp, slanting shadows across the lawn and the curving gravel drive.

Aurelia turned, and in the cheval glass that faced her from the opposite side of the room she caught a full-length glimpse of herself. The sunlight streaming in from behind outlined her slenderness through her nightgown of thin white cotton, and rimmed her hair like a halo; yet no saintliness did she see in that reflection. Her face was in shadow, so she moved forward and studied her features more intently. Her eyes were intensely blue, but still wet with her tears. Her lips were full and, according to him, delightfully kissable. But he was not there to kiss her. Those lips had not enjoyed the intimacy of loving caresses for many long months, and she sorely missed the intimacy.

Although she was lonely, she appreciated the sensation of sleeping alone in this, her bedroom. There was a time when she would never have expected to leave the marital bed, but events had ultimately dictated it. It was now her private domain, her own fortress. Within its confines she could shut out the rest of this cold and cheerless house, which she shared with her cold and cheerless husband. She no longer felt any part of it, nor of him. Within this fortress she savoured her privacy; it protected her. It protected her especially from any unwelcome invasions from her husband. It safeguarded her things; those on the washstand, her potions, lotions and brushes on the dressing table, her chemise draped over a chair, other flimsy essentials lying on the ottoman.

This fortress was spacious, but dauntingly, hideously furnished. It occupied a corner of the first storey and in each outward-facing wall was a window, curtained with ancient pink and blue draperies that had faded long ago. One window overlooked the front garden and the gravel drive twisting through it, which led to the main road connecting Brierley Hill with Dudley. Despite being set well back from the highway you could still hear the clatter and huffing of steam trams, and the rattle of carts’ wheels as they trundled by.

Aurelia’s late father-in-law had built Holly Hall House, that mausoleum in which she lived so unhappily and so alone, except for the quiet and loving companionship of her young children. Through her husband’s lack of will to render it more modern it remained defiantly a shrine to the old man, a mix of the fussy ornateness of French Empire and the sombre bulkiness of 1860s English. Rich swags and wall coverings with swirling arabesques vied for irrelevance with oil paintings of noble stags set amid backdrops of Scottish hills and lochs. These dubious, incompatible niceties, these manifestations of questionable taste, these affectations of wealth, were not Aurelia’s cup of tea, but her attempts at moderating and modernising such long-established extravagances had hitherto proved fruitless.

Aurelia was twenty-four years old and, from the moment of her marriage at nineteen, her destiny was fixed; the pattern of her life was irreversible and fated to be miserable. Never had she felt that she belonged in this house. Always she felt she was just a trophy, destined before long to become a superfluous, unheeded trophy at that, a mere visitor who had no sway and no influence. For this house and everything in it belonged to her husband Benjamin by right of inheritance. It would never change, never be allowed to change, not because everything in it was sacrosanct but because Benjamin had no interest in changing it. They had discussed her ideas and he had dismissed them; why change what was not necessary to change?

Nevertheless, while the house, its material contents and even Aurelia, belonged to Benjamin, Aurelia’s heart did not.

It had long been her intention to generally brighten up the ambience of her private fortress, to change the décor, the wallpaper, the curtains, the eiderdown – when circumstances might permit. Within its four walls a small bookshelf spanned a writing bureau. A book, with a bookmark peeping out, lay on a bedside table alongside a photograph of her late mother. Poor mother, she thought fleetingly as she glimpsed it. Significantly, no photograph of her father was in evidence.

Her wardrobe door was ajar. She reached inside for her dressing gown, duly wrapped it around her and tied the cord at her waist. Another day to face, she thought, one more day destined to be as dismal as any other, with more miserable, empty hours, save for the time she would spend with her children.

She opened her bedroom door and stepped silently onto the landing. With a stealth acquired only by a fervent desire not to waken her husband Benjamin, she stole past his bedroom, supremely careful not to make a sound and thus have to face his long-faced indifference earlier than need be.

Noiselessly she pushed open the door to another bedroom across the landing. In that room her small son Benjie (she preferred to call him Benjie and not Benjamin, so as to differentiate him from her husband) was sleeping the exquisite soft sleep of childhood. She peered lovingly at his dishevelled head, and was moved almost to weeping again, but this time by the look of absolute innocence in the demeanour of his repose. The child’s blissful ignorance of the traumas of living she would preserve for as long as possible – especially the bewildering lives of her and her husband. She pondered how he would turn out when he grew up. Would he be wayward, irresponsible, at times charming, often detached, ruthless in marriage, inept in business, like Benjamin? Well, not if she could help it.

It was early, and little Benjie was sure to be asleep in his bed for some time yet. So she crept along the landing to where Christina, seven months old, lay in her cot, in a room which adjoined Joyce’s, the nanny. The baby roused when Aurelia entered, as if instinctively sensing her mother’s presence. Aurelia gently let down the side of the cot and picked up Christina, who was rubbing her eyes now. She gently clasped the child against her breast, cooing soft sounds of comfort, hoping not to rouse Joyce, for the connecting door was ajar.

‘Let’s go down and see if Jane has lit the fires and put some water to boil,’ she whispered, ‘and we can change your napkin.’ She carried the baby onto the landing and down the sweeping staircase of that large and soulless house.

Jane was the middle-aged maid, devoid of youthfulness and prettiness, round of face and belly, and flat of foot. Life had rendered her utterly certain of a few things, but she remained content in her ignorance of everything else. However, in the short time that she had been employed at Holly Hall House, she had become an expert on the souls of its inhabitants. She was proving to be a conscientious and reliable servant and Aurelia respected her for it. Pretty girls were no longer considered for domestic service; experience had taught Aurelia that pretty girls, who could open doors with smiles and beguiling glances, were far too dangerous and fair game for your husband.

‘Mornin’, ma’am,’ Jane greeted when she saw Aurelia. ‘I’m just brewing some tea. It’ll be ready in a trice.’

‘Thank you, Jane. I’ll be in the morning room with Christina.’

‘Very good, ma’am. Oh, and the post’s arrived already. It’s on the bureau in the hallway.’

Aurelia smiled her thanks at receipt of this trivial information and casually strolled to the hallway, still holding the child. To the ticking of the grandfather clock that had witnessed so many of her domestic and emotional crises, she sorted through half a dozen envelopes. All were addressed to either Benjamin Sampson, Esq., or his company, the Sampson Fender and Bedstead Works.

* * *

Not so two days earlier. Two days earlier, a card within an envelope arrived, addressed to Mr and Mrs B Sampson. Since her own name was upon it, Aurelia felt justified in opening it. It was an invitation to a wedding, and read: ‘Mr and Mrs Eli Meese request the pleasure of the company of Mr and Mrs Benjamin Sampson at the wedding of their daughter Harriet to Mr Clarence Froggatt, on Sunday 4th September at 2.00 p.m. at St Michael’s Church, Brierley Hill, and afterwards at the Bell Hotel assembly rooms.’

Her immediate reaction was surprise, even though she was aware that Clarence and Harriet were stepping out. ‘So, he’s marrying her,’ she uttered to herself, but not without feeling an acute pang of envy for Harriet Meese.

* * *

Chapter 2

One afternoon in the sweltering heat of August, Benjamin Sampson lay drained after a round of enthusiastic lovemaking. But for a sheen of perspiration and a pearl necklace, Maude Atkins lay naked beside him. He ran his fingers over her belly, thankful she had regained her figure so perfectly after giving birth to his child ten months ago. Not only did he still lust for Maude, but he always felt more at ease with her than with his wife Aurelia. She stimulated his sexual appetite in a way Aurelia had failed to do since the novelty had worn off after the first few weeks of their marriage. Maude was an extramarital treat, compliant and spirited. In the bedroom she was a whole heap of fun and enthusiasm (enthusiasm that boosted his ego, for it convinced him that his sexual prowess must be unsurpassed). She was less complicated too, blessed with a forthrightness, as well as a perception of life’s realities, which often troubled him. But he always knew where he stood with Maude, and relied on her judgement more than he realised.

With a singular lack of feminine guile, Maude had persuaded him to provide a house for her and her illegitimate child. It was to her ultimate benefit, of course, but he was not slow to realise there was some benefit for him as well in the arrangement; it served not only as a home for this second, unofficial family, but also as a secret and readily available love nest where he could slake his sexual thirst. The better side of his nature – his conscience – was also in some measure eased, because convention ruled that he could only ever be a part-time companion for her, stuck as he was in an unsatisfactory marriage with Aurelia.

Maude’s vision went way beyond this, however; she had more far-reaching aspirations, and her aim was to persuade him to get rid of Aurelia, for she fostered the ambition of being the next Mrs Benjamin Sampson.

‘I’d better go.’ He murmured, and stroked her thigh, savouring its warm, sensual smoothness, before he stretched lethargically.

‘Why don’t you wait till your daughter wakes?’ Maude whispered peevishly. ‘You don’t see enough of her as it is.’

‘How soon before she’s likely to wake?’

She shrugged. ‘Half an hour maybe. She sleeps till about four, as a rule.’

‘No, I’ve got to go. Something cropped up at the works earlier. I’d better see if they’ve sorted it out. I’ll see Louise next time. You know how it is – time and tide…’

With little enthusiasm for leaving, Benjamin swung his legs out of bed and stood up. He grabbed his long johns from the bedrail and pulled them on, then his vest, then his shirt, which he buttoned up and tucked into the long johns.

‘Shall you pop back later?’ Maude asked, fingering the pearl necklace – a recent gift from Benjamin.

‘Course, if I get the chance. Failing that, tomorrow.’

She nodded her understanding, reminded that she was just a kept mistress, and that circumstances, maybe even of the marital kind, might prevent his presence.

‘Has your beautiful wife decided what she’s going to wear for that wedding you’re going to?’ There was grudge in her tone. The wedding, which was to Maude irrelevant, was to occupy him and frustratingly keep him from visiting her. If only the day would quickly arrive when she herself was openly regarded as Benjamin’s official companion, instead of his closet mistress.

‘How should I know?’ he answered with a shrug. ‘I imagine she and her dressmaker will have concocted something between them.’

It was in his interests to appear indifferent to his wife’s couture so as not to arouse Maude’s jealousy too much; Maude could be a handful, and might even withhold her favours for a day or two. A mistress was for pleasure and a little tenderness, to spice up one’s otherwise dull life and add a bit of comfort to it, not to be cold, indifferent and a source of irritation or enforced celibacy. He suffered enough celibacy at home.

‘She must cost you a tidy penny in silks,’ Maude remarked pointedly.

He made no reply as he pulled on his trousers and buttoned up the fly.

‘I don’t know how she’s got the nerve,’ she added for good measure, her scorn as edged as a shard of glass.

Benjamin shrugged again and, without meeting her eyes, decided it might behove him to act a little stupid. ‘How do you mean? For going to the dressmaker, or for presenting me with the bill?’ He pulled his braces onto his shoulders.

‘She’s got you for a nincompoop.’

‘Oh, I’m no nincompoop, Maude,’ he declared, irked at her indictment. ‘I’m just biding my time.’ He began attaching his collar.

‘Biding your time, my foot.’ Maude sat up, striving but failing to conceal her own agitation. She turned to adjust the pillows behind her while Benjamin’s eyes lingered on her breasts, full and round, bouncing with tantalising pliability as she twisted her naked torso. ‘Why ever you had her back after she left you I’ll never know.’

‘She was expecting a child.’

‘Yes, her second…But whose child? Not yours.’

‘Oh? Who else’s could it have been?’ He reached for his necktie, also hanging on the bedrail.

Haughtily, Maude shook her mane of mousy hair. Here was the perfect opportunity to really make him see. ‘Benjamin,’ she began, leaning forward and pronouncing his name with charged emotion, ‘in the first place, your beautiful wife left you for another man, and she came back when that man spurned her just as soon as he knew she was carrying his child. Either he wouldn’t, or couldn’t, have anything more to do with her. So she came back to you. It’s the easiest thing in the world for a woman to dupe her husband into believing the child she’s carrying is his. She did that to you, and you fell for it good and proper.’

‘You don’t know it for a fact, Maude,’ he replied defensively. The notion that somebody might have made a cuckold of him he dismissed, for he considered himself too smart to be duped by a mere woman, however much she might be admired and desired by other men. So he tried to convince himself that Aurelia could not have been unfaithful, that it was not in her nature to be unfaithful. Yet he tried to recall the times he might have coupled with her, rare as they were, during the time when she must have conceived.

‘You don’t have to be Sir Isaac Newton to work it out, Benjamin,’ Maude went on. ‘I know what women are capable of, even if you don’t. Whenever you went away on business, she’d be off as well, flying her kite somewhere with somebody else. Some nights she didn’t even come back home.’

‘Hearsay, Maude. That’s only what Mary, that damned unreliable slut of a maid we used to have, told you. She was a mischievous little bitch with an axe to grind, and the biggest liar in Christendom to boot…’

‘I lived in that house as well, Benjamin, remember. I was nanny to your son, almost from the moment he was born. I knew what was going on.’

He paused, pondering again the strength of the allegations, and the conviction with which Maude delivered them. ‘If Aurelia had been unfaithful I’d have known,’ he said with dwindling certainty. ‘She’s a fine-looking young woman, so it ain’t surprising men fancy her, but who on earth could she have been carrying on with?’

‘I would have thought that obvious.’

‘Well, it ain’t obvious to me. Pray, enlighten me.’

‘Clarence Froggatt, who else? That nincompoop whose wedding you’re going to…She was engaged to him once, you told me so yourself…’

‘You think she was seeing Clarence Froggatt behind my back?’

‘Yes, for ages.’

‘Never.’

‘Oh, I’m sure of it.’

Benjamin pondered the suggestion a second or two more. ‘But it doesn’t add up,’ he said eventually. ‘He would hardly be marrying that girl Harriet Meese. I mean to say, compared to Aurelia she’s a gargoyle. God must’ve given her the plainest face he could find, and then hit it with a shovel. So why would he settle for a plain Jane if he could have a pretty one? It ain’t in a man’s nature. Aurelia is a good-looking young woman, even you have to admit that.’

‘But maybe he realised he could never have Aurelia – she being already married to you…Anyway, as far as her looks are concerned, beauty is only skin deep,’ Maude added with another outpouring of scorn, for she could never admit that Aurelia was beautiful.

‘But your beauty goes deeper, eh, Maude?’ He winked at her and grinned, in an effort to remove the intensity, which was becoming rampant in the discussion.

‘Oh, go on with you.’ Maude allowed herself a smile; there really was no doubt whom he preferred bedding, and the knowledge induced a renewed warm glow. She was reassured that at least she had this hold over him, this delectable sexual allure. He kept coming back for more. He loved it, and so did she. ‘So I might see you later, then?’

He picked up his jacket, went over to her and kissed her. ‘I reckon,’ he grinned, and tiptoed down the narrow, twisting staircase.

* * *

Benjamin Augustus Sampson, twenty-seven years old by this time, was the sole issue of the late Benjamin Prentiss Sampson, and thus the sole beneficiary to the old man’s estate. Part of that inheritance was the once thriving Sampson Fender and Bedstead Works, which the son Benjamin had contrived to expand, albeit unprofitably, into the new and challenging world of bicycle manufacture. For young Benjamin Augustus lacked the acumen, commitment, integrity and foresight of his father, who, from excruciatingly humble beginnings, had become a self-made man.

Young Benjamin, however, was not particularly interested in the manufacture of anything. The factory existed merely as a tap to provide a continuous but diminishing supply of money; money that he took for granted and spent unwisely. He failed to understand the mysteries and mechanics of how it was generated, or indeed why it should dwindle. It was a tap that dripped uncontrolled, always lowering the level of the reservoir that had been its working capital.

As an only child Benjamin had wanted for nothing, and in adulthood expected everything. He understood little about, and appreciated less, what his father had achieved, or how he had achieved it. Nor had he ever come close to appreciating the astonishing setbacks his father had overcome to be so successful.