Полная версия

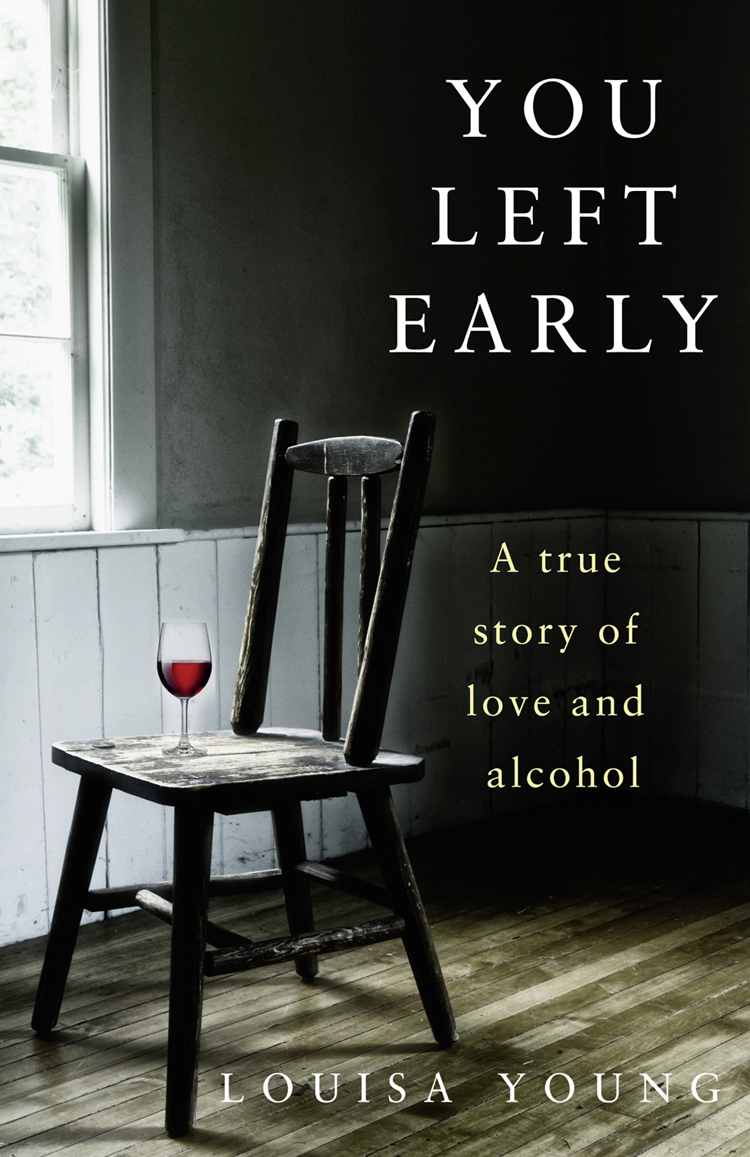

You Left Early: A True Story of Love and Alcohol

Copyright

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Louisa Young 2018

Cover photographs © Margie Hurwich/Arcangel Images, © Shutterstock.com

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Louisa Young asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the author’s experiences. In order to protect privacy, names, identifying characteristics and details have been changed.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008265175

Ebook Edition © June 2018 ISBN: 9780008265199

Version: 2018-07-18

Dedication

For everyone who has found themselves here

Epigraph

Inversion of Intervals:

Major becomes Minor.

Perfect stays Perfect.

Augmented becomes Diminished.

from Robert Lockhart’s

music theory notebook

1969

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction: The Book You Hold in Your Hand

Part One 1959–2002

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Part Two 2003–05

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Part Three 2005–07

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Part Four 2007–09

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Part Five 2010–12

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Part Six 2012—

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Appendices

Footnotes

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Louisa Young

About the Publisher

Introduction

2017

The book you hold in your hand is a memoir by me, Louisa Young, a novelist, about Robert Lockhart, a pianist, composer and alcoholic, with whom I was half in love most of my adult life and totally in love the rest of it. It’s as much about me as about him, and is of necessity a difficult book to write. So why am I writing it? Why expose, so openly, chambers which are only usually displayed via the mirrors and windows with which novelists protect their privacy?

Because his life is a story worth telling.

Because our love story, while idiosyncratic, is universal.

Because alcoholism has such good taste in victims that the world is full of people half or totally in love with alcoholics – charismatic, infuriating, adorable, repellent, self-sabotaging, impossible alcoholics – and this is hard, lonely, baffling, and not talked about enough.

Because although there are a million and a half alcoholics in Britain, many people don’t really know what alcoholism is.

Because alcoholics also love.

Because I don’t want to write a novel about an alcoholic and a woman; I want to write specifically about that alcoholic, Robert, and this woman, me.

Because everything I have ever written has been indirectly about Robert, and the time has come for me to address him directly.

Because the last time I tried to address it directly I told him, and he said, ‘You won’t be able to finish this until I’m dead.’

Because I have realised that for me, quite the opposite: he won’t be properly dead until I’ve finished it.

Four months after he died, I wrote this:

It can’t be surprising that I can’t write now. All I can think about is Robert and death, so that is all I could write about, but I can’t. To write Robert would be to seal him. I, who can rationalise my life into any corner of the room and out again and rewrite my every reality in any version I like, and back, twice before lunch, I cannot pin that man to the specimen paper. I cannot claim to have all of him in view at one time. I cannot slip him into aspic, drown him in Perspex, formalise him – look, there he is in that frame, that’s how he was, that’s him. No, that is not him. He is an alive thing. His subtleties and frailties are living things. I cannot bind to myself or any other place the joy that he was. It makes no sense to me for him to be dead. And when it does make sense to me, as no doubt it must at some stage, then – well then he is even deader, because I will have accepted it. And I do not accept it. I do not want to accept it. I reject it. I say to death: Fuck off.

But I am a writer, and without writing I was bereft. And God knows I was bereft enough already. I have so much and yet these have been years of loss. Each loss lost me something else as well. Losing Robert lost me writing. I wanted to talk to him about it. Instead there I was, writing about not being able to write: If I write this book, am I preventing other versions? Will making this our conversation disbar me from remembering other things we said? Am I bruising my memories by handling them? If I file them, will I ever find them again? Will their bloom be intact?

I was always terrified of losing him; I lost him a hundred times and had him back. I wanted him back yet again. His nine lives, the nadirs he specialised in. I thought: he wouldn’t really be dead. It’s so unlike him.

This is my version. Anyone who knew him will have their own version. I understand that. I’ve done my best to balance open honesty about this illness with sensitivity.

Chapter One

Uxbridge Road, 1990s

Beirutsbridge Road, he called it. This neighbourhood! Between charming Holland Park and its neighbour Shepherd’s Bush there is a difference in life-expectancy of eight years. A six-foot woman pushing a buggy yells ‘I’ve got my child wiv me ’ave some fuckin’ respect’ at me for no reason I can imagine, unless it’s that I’m wearing only one blue paper flipflop following a pedicure-related broken-blue-paper-flipflop incident. Then a big West Indian man comes towards me, with a tiny Thai man trying to pat his – the big man’s – back and wipe something off his – the big man’s – front at the same time, both of them giggling. A scrawny pasty-faced undertaker in his frock coat walks by, swigging Diet Coke from a bottle. A tiny pregnant person who says she’s Greek but I’m not sure she is wants some money, so I give her some and direct her to the Greek church, but I don’t think she understands. An old Spanish man informs me that he’s seventy-one; I say Happy Birthday, he howls with laughter and says ‘Happy New Year!’ There are giant yellow tubes piled up all down the middle of the road. A barefoot man goes by on crutches, his feet swollen and dry and sad; he gives me a glance of barefoot complicity, but mine are bare out of vanity, not need. I wanted to get home, but I didn’t want the nail polish to smudge. It’s Dickensian. A barefoot man on crutches.

Always, walking down this road, heading west from the Tube station to the street where I have lived for twenty-five years, to the house where he had so often pitched up over the decades, and kind of lived with me for ten years, I look for Robert: leaning in the doorway of Paolo’s cafe, beaky nose, skinny legs, having a cigarette; coming out of Jay’s newsagent, hobbling across the road from the Nepalese restaurant popularly known as the Office, in the brown velvet-collared tweed coat I gave him after he left the dark blue one on the train to Wigan; or the old leather jacket, or the new old leather jacket, in his jazz-cat hat, hunched like a grey heron at the edge of the city street, being liminal, looking about him, in the rain, or the sunshine, perhaps sitting outside a cafe, newspaper, cigarettes, espresso, pencil, sketches of a melody in the margins of the sports section. In later days, glasses, and crutches, or the two ugly black walking sticks with ergonomic handles shaped like bones.

In his youth he was beautiful like an off-duty Bowie – skinny, pale, romantic-looking, naughty, with something fugitive about him; he was always about to leave. In maturity, a craggy battered face, Northern, a big bent nose, a small chin, no eyebrows to speak of, cheekbones, a broad brow, small scar to the left, brown to grey hair tending to the fine and fluffy unless smoothed back, from which it benefitted, plenty of it, usually either too long or too short, always badly cut, because I did it, because he wouldn’t go to the barber. Widow’s peak. A bashed pale mouth, thin lips, curled in some sardonic look often enough. Big flat English ears. Beardwise, kind of bald on one side, a bit goatee-ish on the other; a wiry moustache which could have been elegant with the slightest bit of care. The odd pockmark. Glasses – whoever’s, it didn’t matter much. A bit Ted Hughes, a bit Samuel Beckett. All crag and stoop. Eyes? Yes, he had eyes. They were blue, and much clearer than they had a right to be. I may come back to them. Right now they are staring at me from various photographs, and, writing this, I see him looking at me, and my tears come up again and I need to go and rail against horrid fortune which made him as he was and not just a tiny bit different.

I see him, sometimes, in the criss-crossing currents of people. But he is not there.

Chapter Two

Primrose Hill, Wigan, Oxford, Battersea, 1982

I know for a fact which balcony it was. It has grown mythical in my mind: the balcony on to which he invited me, where he first kissed me, though I can’t actually remember the first kiss. But I remember the thrill of him wanting me to go out there with him. First floor, overlooking the park, leaves – plane trees? A very London balcony, as seen on the first floors of many handsome white stucco London houses of the mid nineteenth century.

It was our mutual friend Emma’s party, in a first-floor sitting room with long windows. We were twenty-two, twenty-three, at the stage where you go to parties in flocks, losing and gaining companions in the course of the night. I recall it being crowded, glamorous, noisy. I recall my little thrill at the sight of him.

I’d met him before. The first time was on a staircase in an Oxford college in 1976. We were going in and he was coming out. (‘We’ was me, my childhood friend Tallulah and her calm, amiable law-student boyfriend Simon, who we were visiting, and whose new friend Robert was.) I, a born, bred and dedicated Londoner, had never met a Northerner before, never heard gravelly basso profundo Wigan profanities coming out of a skinny whiplash chips-and-lemonade body. An old cricket blazer of some kind hung off him; clearly not his. He had that romantic demeanour of consumptive turn-of-the-century sleeplessness and intense energy – what my father called ‘pale and interesting’ (I was more pink and interested). He was gorgeous, incandescent. And leaving. He may return. Please return was my only thought.

He did return. He was at an upright piano between two windows, playing – Chopin? Debussy? People piped down. Girls were leaning over him. With my usual instinct to avoid what was attracting me, I went to the other end of the room and stood looking cross with my back to the wall. Oh, I knew how to let a chap know I liked the cut of his jib. And I listened. As someone said years later, ‘It was different when Robert played.’ It was. He was mesmerising. And he knew it, and he used it, and he was not comfortable with it.

People talked about him. He’d won his place to read music at Magdalen from Wigan Comprehensive (formerly Wigan Grammar) at the age of sixteen. (I, a day older than him, had only just passed my O-levels.) By seventeen he was a demy, a half-Fellow – this is a form of scholarship for ‘poor scholars of good morals and dispositions fully equipped for study’. Previous incumbents included Oscar Wilde and Lawrence of Arabia. By his third year he was teaching the first years, and he graduated at nineteen with a double first, twice as good as the normal and tragically insubstantial single first, which was clearly not good enough for him. He’d got Ds in his two other A-levels, French and German, and had massive streaks of ignorance about everyday subjects. Two highly knowledgeable musicians recently – and separately mistook a tape of the young Robert playing for Arthur Rubinstein.

Child prodigy? Massive over-achiever? Cultural cliché? Chippy Northerner? Workaholic artist? All of the above?

‘There’s no fuckin’ frites on my épaule,’ he said.

There was a song he used to sing:

‘We’re dirty and we’re smelly,

We come from Scholes and Whelley,

We can’t afford a telly,

We’re Wigan Rugby League, diddley de dum OI OI.’

He would do it in broad Wigan – ‘We coom fro Scerls’n’Welli’ – or, for variety, in a posh, southern, actor-y manner: ‘We come from Scales, end Welleh, we carn’t, afford, a telleh …’ Alongside his exceptional ability on the piano, it made an amusingly ambiguous impression. No Brit is left untouched by the terrible four – class, geography, money, education – and there was an assumption among Oxbridge undergraduates at that time that Northern = working class. The niceties of ‘Rough’ v ‘Respectable’ working class, or respectable working class v lower middle class, were pretty irrelevant in that world. It all counted as Not Posh. Sometimes when posh people realised Robert wasn’t entirely working class they would say he pretended to be, and resent him for it, when in fact it had been their own presumption in the first place. Once, for a week, he made a conscious effort to get rid of his accent. Then he realised people noticed him because of it, and that as long as he could put up with the mockery it was actually an advantage. People whose class is unexpected can get away with things. They can be seen by the class they are arriving in as somehow superior, gifted with knowledge from the other side. It can work well for intelligent, socially mobile working-class boys: their strangeness confers a powerful status – which in turn contributes to the anxiety of the uprooted, those who by being socially mobile become psychologically divided.

In his uncomfortable, nervy move south and up, Robert did sacrifice pronouncing book to rhyme with fluke. In Wigan once, a cabbie taking him home from the station wouldn’t believe he was from there, saying ‘Ner, yer not’ as Robert, upset, insisted. Meanwhile in Oxford and London he remained the most Northern thing anyone had ever seen. He never rescinded his Northern passport, preached the gospel of rugby league daily (and interminably), and replaced bath-to-rhyme-with-hath not with bath-to-rhyme-with-hearth but with, every time he used the word, a piss-takingly long, self-aware and scornful barrrrth. He couldn’t use the word ‘dinner’ without either a sarcastic accent or a short monologue on why he wasn’t saying ‘tea’. People were often accused of mitherin’ and maulin’ him. Checking there was enough cash for an outing, he’d say ‘As geet caio?’, a usage so arcane I doubt there’s a Wiganer alive now who’d use it other than in nostalgia and irony. But then those two never quite sorted out their differences in Robert’s first-in-the-family-to-go-to-university heart.

His was not a childhood of clogs and tinned food – they had a piano, records, laminated recipe cards – but he was familiar with factory sirens and rough lads and the River Douglas – the Dougie – running a different colour on different days of the week because of the dyes. He loved Les Dawson and explained to me the source of his silent exaggerated mouthing: the ‘mee-maw’ that women working the mills would use to make themselves understood over the sound of the machinery. And he reserved a lifelong interest in people who, like him, made the risky, lonely leap of class: David Hockney, Alan Bennett, Jeanette Winterson, Keith Waterhouse, Victoria Wood, Dennis Potter. Especially if they were drinkers: Dudley Moore, Richard Burton, George Best, Gazza.

At Oxford, with people he didn’t know well, who all seemed to sound like the BBC and wear Eton ties, he felt he had to assert himself to be noticed. He didn’t like to be ignored. He wanted to experience everything at once, to lead a life as intense as it could be, to go to bed with as many women as possible, see everything, do everything. ‘It’s what you do in these sorts of moods that gets you a bad reputation,’ he said to a friend who wrote a profile of him for a student magazine. ‘And when I’m in one of them I really revel in my reputation.’ But he also wanted an introverted life, writing music, reading, with a real relationship, warm and secure and emotional. Then, he said, he despised his other self for sleeping anywhere, and putting up a huge facade. He was really a romantic. ‘Just one note,’ he said, ‘a particular chord, can give me an incredible sense of, well, it can’t be nostalgia, because it’s not for anything in the past. I suppose it’s more like nostalgia for another world …’

Robert was very popular. His legends abounded: the time his tutor popped in to see him, and a naked girl was playing his piano. The occasion when a scorned admirer – male – dropped an empty champagne bottle from a high window, just missing Robert’s head – Robert was convinced it was a murder attempt. The pissing in the sink so often it had to be removed, whereupon he just pissed out of the window. The Dean of Music calling in to wake him every day around noon. The dancing naked on the lawns; the streak across the river during an Eights Week boat race, pursued by loud-hailing patrol boats. And, as a female friend said years later: ‘He slept with everyone except me and Benazir Bhutto.’

People mooned over him. I’m not bloody mooning over you, I thought. So proud! I longed to moon over him. I was SO romantic, and the only thing I was more so than romantic was proud. And of course I found him SO romantic, and so of course, because I was seventeen, He Must Never Know. Also, I was narked about him being two years ahead of me academically, though a day younger, and fully state-educated where I was only half, which to my mind gave him a cracking moral advantage. I went from a posh Lefty West London home – ‘don’t say pardon, say what’ – to a state primary – ‘don’t say what, say pardon’ – and then to the kind of highly academic girls’ private school which told us that we were better than everybody else. Some of my coevals took this as read, and are currently running the world; those who knew it not to be true tended to slump to the polar opposite and believe themselves to be worse than everybody else, and certainly Not Good Enough, hence the prevalence of drugs and eating disorders among pupils at those places; or, in my case, a mildly dysmorphic conviction of my own fatness, and cider. I grew up drenched in all that should have made me feel at home when I went to university at Cambridge, from accents to architecture, yet found myself bemused, class- and location-wise. Three thick card invitations in the same envelope, to a ‘dinner party’, a ‘dance’ and a ‘house party’, all from names I didn’t recognise, on the same night, at different addresses, in Hampshire where I had never been – what was this? I quietly asked a country-gentry type I knew. He sneered at me, for ‘faux naivety’ and ‘inverted snobbery’, for, as he saw it, pretending not to know. But I didn’t know. In London, at nineteen, dinner was a doner kebab on the night bus; if you stayed over after a party it was because you fell asleep on someone’s sofa. Being sneered at by someone who considered himself my social superior was … educative.

*

At Emma’s, I remember a long sofa against the wall; sitting on it with him being, as we later called it, Lockharted – being tested and chauved (a Wigan verb, meaning to wind someone up), regaled and assaulted with a barrage of combative and contrary wit, filthy flirtation and intense, wilfully polysyllabic musical erudition which made strong men weak and weak girls melt – and some people, of course, sidle off in bemusement and/or disgust. Gesualdo’s duel, Schubert’s syphilis, my bra strap, Bill Evans, more wine, Red Garland, Singapore laksa, Argerich’s rubato … He was a centre towards which things spun. So when you’re on the sofa with him, the focus of him, getting all of it, the intensity, immediacy, challenging, drinking, smoking, the you – here – now. I want yer – there was a tendency to go ‘Whoa!’ and fall into the tidal wave.

Seeing myself as fat and not what boys wanted, I drank too much and had had my heart severely broken at university. I wasn’t stupid, but I was dismally blind when it came to reading men’s intentions towards me: I got into situations. It was still, just, the era of ‘men’ and ‘girls’. I did agency work (security guard, catering, tea-lady in a parking meter factory) and lived in a squat and wanted to be a writer but I had nothing to say on paper and I knew it. I was frustrated and not good at going after what I wanted. I knew exactly how lucky I was, and I suffered the paralysis which can affect intelligent posh girls, saying to them ‘You have been given so much; you with your education and your stable family and your prosperity and your accent, seriously, you’re asking for more?’ I thought to be loved you just lived your life until someone turned up and loved you. I did actually think, like Shakespeare’s Helena, that we cannot fight for love, as men may do; we should be woo’d, and were not made to woo. It didn’t occur to me to go out and get them. Quite often I stayed in bed reading because it was easier. Looking back at me, I might say I was depressed. Emotions were extreme.