Полная версия

You Can Conquer Cancer: The ground-breaking self-help manual including nutrition, meditation and lifestyle management techniques

Experience says it is very difficult to think clearly, to make good decisions, to really commit to what you need to be doing, if your emotions are all over the place. Once the immediate emotional response to a diagnosis is felt, expressed, and showed, usually the intensity goes out of it. Maybe emotions will arise again in the future. Again that would be natural and normal. But be authentic. Be comfortable with your own degree of emotional expression and realize emotions are another natural part of a healthy life.

So do take time. Sit with those you are close to. Be with them. Maybe in silence. Maybe with tears. Maybe with talking and discussion. Take it in. Let it out. Allow yourself to settle. And then begin to plan. To move forward again.

Chapter 2

Keeping Hope Alive

Prognosis and Looking into the Crystal Ball

While diagnosis is based on fact, prognosis is based on speculation. With a prognosis comes an attempt to predict the future, to give an informed estimate of what the diagnosis, along with any treatment, is likely to lead to.

The problem with a prognosis is that it can have power in its own right.

In the ancient culture of the indigenous Australian Aborigines there is a phenomenon called the “pointing of the bone.” This culture is the oldest continuous culture on the planet and its roots stretch back in time for at least forty thousand years. Many of the Aboriginal tribes lived in small nomadic groups that thrived amid extremely harsh environments. To survive and flourish they had quite strict laws that everyone recognized and generally adhered to. One of the ultimate penalties for transgressing these laws was the pointing of the bone. Here is how it works.

If a person broke a major law, they would be very aware of it themselves. They would know something serious was wrong and they would be aware of the likely consequences. Once the transgression was recognized by the tribe, the senior people would confer, and if all agreed, the punishment of pointing the bone would be carried out by the senior law holder. This person, often referred to as a man of high degree, would dress up in ceremonial garb and the instrument of the punishment literally would be a bone—a human thigh bone.

But there was no beating or physical assault with the bone. It was “pointed.” Amidst the ritual of the process, the bone was pointed at the transgressor along with the words—the curse, if you like—the threat, the promise, that the person would die.

Interesting things would begin to happen immediately. First, the law-breaker, the person who had been pointed, would go into a rapid decline. Then, all of the tribe would withdraw and avoid contact with them. The person would become depressed, lose all interest in life, then they themselves would withdraw and become listless, apathetic.

At this point there are frequent records of Western medicine attempting to intervene. No conventional treatment has been shown to prevent the ongoing decline toward death.

As death approaches, another significant observation. The tribe members, sensing the closeness of the end, gather around again. This time they go into pre-mourning rituals and, in the process, seal the fate of the wretched victim of this extraordinary punishment.

So the pointing of the bone is invariably fatal in this Aboriginal context.

Now let us make some unnerving comparisons. A person knows they are not well, that something serious is wrong. They go for help. Senior people confer. Then comes the consultation where the key figure dresses up in ritual garb, with white coat and stethoscope, and makes a pronouncement.

When bad news is given badly, there are all the hallmarks of the pointing of the bone.

“You have only three months to live and there is nothing we can do about it.”

In days gone by the message was often given this bluntly. These days, many doctors attempt to be more subtle and compassionate, but even so, many people get the take-home message: you have cancer, you will die.

All too often what happens next is that they go home in shock, they withdraw and then so do their friends. Often friends, even family, are unsure of what to do, how to respond, how to help. Many of these people, well-meaning, kind and considerate in their nature, have told me how they were deeply concerned about doing or saying the wrong thing and so they thought it safer to do nothing, to stay away.

However, if a person with cancer does decline and seems close to death, it is common for people to gather around to say their good-byes. This is natural and we will discuss how to do this in a healthy, constructive way in the chapter on death and dying, but here again, done badly it can fit exactly into the pointing of the bone process.

The message is simple. If bad news is given badly, if a prognosis is given bluntly and taken to heart, the person affected may well have two life-threatening conditions to deal with. The first is the actual illness. The second is the “pointing of the bone.” And we know both have the potential to be fatal.

Traditional Aborigines have survived the pointing of the bone. There are accounts where Aboriginal elders or today’s doctors have used their own rituals to persuade the person who has been pointed that the punishment has been countered or reversed. No medicine will do this. It all needs to come through the mind of the individual who has been pointed.

Therefore, we need to take heed of all this. For a start, let us use our logic again. In reality, offering a prognosis is a bit like setting the odds on a horse race. While in cancer medicine this process will involve high levels of technical skill and clinical expertise, setting a prognosis remains a process of making an informed guess. One takes into account all the factors one can and then makes the best estimate possible.

Now, we know that in horse racing the reality is that favorites win quite often. Yet we all know long shots get up from time to time. The only way to find out the result of a horse race is to wait until the race is run. Just the same in life. Just the same with cancer.

A prognosis is a bit like setting the odds. It can be helpful in giving all involved a sense of the degree of difficulty the diagnosis implies. Obviously, the odds of recovering from a cold are very high. No one who develops a cold takes it too seriously and fears dramatically for their future. The prognosis with a cold is usually pretty good and we can afford to treat it rather casually. If someone is diagnosed with a widespread aggressive cancer, obviously that is a vastly different matter and makes for a situation that requires the focused attention of everyone concerned.

You are a Statistically Unique Individual

But let us go a little deeper. Here is some more good news. Human beings are statistically unique events. What does this mean and why is it so important?

Easy to explain. Consider a game of chance like Two-up. Two-up is where you take two coins, each with heads and tails on either side, throw them into the air, and bet on whether they land with two heads up or two tails. If they land with one head and one tail, you throw them again. Imagine now that two heads have come up five times in a row. Most people instinctively feel the next throw is now more likely to produce two tails. Surely, the odds predict this, we think. Not so. Each time you throw two coins, you have a statistically unique event. There is no connection, no link between one throw and the next! Statistically unique. Sure, if you throw two coins one thousand times you are highly likely to have around five hundred heads and five hundred tails. On average, over large numbers, statistics are relevant and work well. But individual events like tossing coins are unique.

So too with people. People diagnosed with cancer are statistically unique. On average, statistics are useful to predict what might happen, to set the odds. That has some validity and some use, but you will never know the outcome for a unique individual until time moves on and the race is run.

Before my own secondaries were diagnosed, I had been into the medical libraries and had not been able to find a record of anyone surviving my type of metastasized cancer (osteogenic sarcoma) for more than six months. If I had accepted this fact, accepted my prognosis, I could very easily have withdrawn, become passive, and died on time. What a blessing in retrospect that I was “crazy” enough to believe it was possible to recover—“crazy” in that to aspire to recovering I went against all the prevailing evidence of the day. However, there is real logic to what I did and how any other person with cancer needs to approach their prognosis.

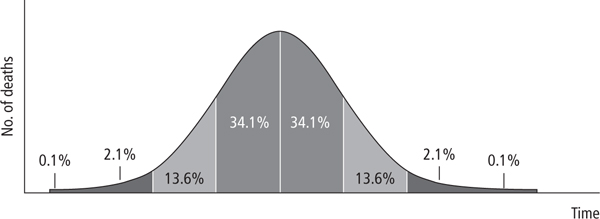

When one looks at the range of outcomes for nearly all situations in life, they commonly vary quite a deal. In cancer it is just the same. The evidence is clear that faced with similar diagnoses, some people will live a long time and some not so long at all. This is often referred to as normal distribution and expressed graphically via the bell curve. The bell curve records how, if, say, a thousand people were diagnosed with a similar cancer, as time goes on, some die soon, most die in average time, and some do live on for a much longer time.

The Bell Curve or Normal Distribution

Where the numbers shown represent the percentage of the whole

The time factors will differ for different cancers and the exact shape of the curve may vary too. But the idea is clear. When a large number of people with a given cancer are tracked, most die around the same time. This is the statistic most prognoses are based upon. Maybe if the doctor is optimistic, it is pushed a little to the right; pessimistic, a little to the left. But the message is clear. This represents statistics.

If you or someone you love have been diagnosed with the same cancer as many other people, their history is interesting and points to what is possible, but not to what is certain. You are a statistically unique event. You could fall anywhere on the curve. That is a statistical fact. That is reality.

The big question then is, what affects where you end up on the graph? Is it simply a matter of statistics and random chance, or will what you do influence the outcome?

Back to horse racing again. If you were interested to back a horse in a race and you knew it was not being fed well, how would you feel? What if it was not well trained? How about if it was one of those horses that did not enjoy racing? Surely, these factors affect the outcome.

So too with cancer. If you embrace a good treatment, what direction will that head you in? If you eat well, will that take you right or left on the graph? Eat badly? If you remain filled with fear and dread, or if you develop a positive, committed approach, what is likely?

Given that everyone is a statistically unique event, everyone therefore deserves to be treated uniquely, to be regarded uniquely. Whether you have been diagnosed with cancer or are helping someone through cancer, your situation is unique. No one else has exactly the same situation as you. No one else has exactly the same body. Your emotions will be different, the state of your mind is bound to vary, and your spiritual realities differ. You are unique.

So two women diagnosed with breast cancer may be described as having the same disease, breast cancer. Just as two men with prostate cancer may both be said to have prostate cancer. Same label, very different situations, very different possibilities. Maybe it is more useful to say one woman by the name of Jane who is diagnosed with breast cancer has Jane’s disease, another Mary’s disease—they could well be that different.

Again, while statistics are useful to generalize, you need a large group for statistics to be useful. The key point is this:

Individuals do not behave statistically. Individuals behave individually.

We are all individuals. If you want an average outcome, do what the average does. If you want a unique outcome, an extraordinary outcome, be logical, regard yourself as you are, unique, and do something extraordinary!

Chapter 3

What Treatments Will I Use?

Attending to Individual Needs

Moving on from diagnosis and prognosis, what about the treatment options? How do you develop a comprehensive treatment plan that is most likely to work and take account of your individuality, your personally unique situation? How to move beyond generalizations and standard treatments, to taking account of individual needs? How do you personalize the appropriate response for your particular situation?

Again, we rely on logic for the framework and then aim to draw on experience, wisdom and insight for the details.

Nearly everyone in the Western world will be diagnosed and consider initial treatment within the conventional Western medical framework. This makes good sense and is as it should be.

Given that the diagnosis and prognosis will be provided by the best medical people available, it is they who will recommend an initial treatment plan. This too makes good sense. Certainly if there were a simple, medical solution to cancer, one piece of surgery, one pill we could take that ensured a cure, we would all do it. You would be a fool not to. But it is not so simple.

Definitions • Curative Treatment, Palliative Care or Living with Cancer?

While the medical treatment of cancer tends to focus on one of two outcomes, to be curative or to be palliative, there is a third option. Let us be clear with the definitions.

Curative Treatment

Curative treatment involves more than what many people imagine it to be, which is to be free of cancer after five years. Actually, curative treatment aims to render the person clinically free of detectable cancer and restore the person to their normal life expectancy.

Palliative Care

On the other hand, palliative care is an umbrella term for assisting those approaching death—a fundamental need and right. It is generally used in the context that death is imminent and inevitable and aims to make dying as easy and comfortable as possible.

Palliative Treatment—Living with Cancer

Palliative treatment is a specific but integral part of palliative care. Palliative treatment can be more interventionist. It is noncurative by definition but aims to extend life, ameliorate symptoms, and increase quality of life in situations where a cure is not medically feasible.

The lines between palliative care and palliative treatment can often be blurred, but these days, palliative treatment is often called living with cancer.

While overall survival rates in the conventional management of cancer may not have improved all that much, in recent years many people are living longer with cancer. This can involve significantly slowing the progression of the disease, minimizing any side effects and maximizing all the quality of life issues. Palliative chemotherapy often plays a significant part in conventional medicine’s management of palliative treatment.

What to do When a Medical Cure is Likely

Now the logic. If a person is offered medical treatment for cancer where there is a high probability of a cure, then, in my view, what to do is fairly straightforward. Embrace that treatment as your main focus while you go through whatever it entails. The common treatment options are surgery—which often comes first—then maybe chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.

However, right at the start or even better still, before you start your treatment there is more to do. As soon as possible, review your lifestyle and do whatever you can to complement and support the treatment with your own efforts. The details of what this entails follow in the subsequent chapters. Lifestyle medicine will have your body and your mind in the optimal state to get the best out of any treatments and to minimize the potential for any side effects.

When it comes to the complementary, traditional and alternative options, there may well be useful things to consider that will support your body’s healing capacity, minimize or manage side effects and have other useful benefits. These options will be discussed in later chapters as well.

The Choices When a Medical Cure is not so Likely

However, what if a cure is not so likely from the medical point of view? What if at first diagnosis, or further down the track, it becomes clear that a medically based cure is improbable? What if palliative care or living with cancer is all that remains medically? There are three options.

1. Acknowledge Death as the Likely Outcome

This is probably not the option you are opting for if reading this book. However, we do need to recognize and accept that some people do accept their prognosis and do acknowledge death as the likely outcome. They then may choose to focus on what can be done to garner the best from whatever time remains, to live with cancer as long as possible and to prepare for a good death.

Yes, prepare for a good death. Death is like everything else in life. We can stumble into it, hoping for the best, or we can prepare for it and, in all likelihood, have a good death. To be open about this, when I started working in the early eighties with others affected by cancer, I knew little of death and I was preoccupied with the desire to help people to recover. I admit to being apprehensive about what would happen if and when people died of their cancer. While many did recover, others did go on to die of their disease. Over the years I have worked closely with many of these people and it has been incredibly heartening to observe how consistently the people I have known who prepared for death were able to die well. What they learned and what they did stood them in good stead, and the quality of their deaths was exceptionally high. We will speak more of this in a later chapter.

For now, it needs to be said that some people faced with the situation where there is no medical cure on offer do accept death. Some are content to focus on living with cancer and are keen to utilize palliative care when the time comes. Again, that is a perfectly reasonable and logical choice. However, if for whatever reason you are not ready, if you do not accept death, and if you are still intent on getting well, you need to be logical. If medicine cannot cure you, what will? Can anything?

2. Seek a Cure from the Nonconventional Medical Options

Remember the different styles of medicine: conventional, traditional (TM), complementary and alternative (CAM). If conventional medicine says a cure is beyond them, do any of the others have a solution? I have the personal knowledge of many individuals telling me that individual TM or CAM therapies were very significant in their recoveries. But I do not have the experience of consistency in this. It seems that from time to time, for some individuals, individual TM and CAM modalities fit really well with that particular person and are highly effective. But I am not aware of a TM or CAM therapy that reliably will be of major benefit to a wide range of people. I do not know of a magic bullet in the realms of traditional, complementary or alternative medicine.

3. Seek a Cure Within—Recovering Against the Odds

Even when conventional medicine says there is nothing more we can do toward a cure, I do believe there still is real hope on offer. Where the “magic bullet” actually does reside is within you. In the face of difficult odds, a cure may be much more likely through mobilizing your own inner healing than through chasing after some elusive external TM or CAM treatment.

Remember, it only has to be done once to show that it is possible. You only need one person to use their own inner resources to recover without the aid of external, curative medical treatments and you know that it is possible. Just one case demonstrates that there is the potential for the body to react, to reject the cancer within it, and to heal. And if it can be done once, it can be done again. And the truth is it has been done many more times than once. What I have been studying and teaching for over thirty years is what makes this most likely to happen.

Clearly, if you aim to recover against the odds, it is not likely to be easy. There is no point misleading anyone here. If it was easy, everyone would be doing it and no one would be dying. My experience is, as we have discussed already, those who do become remarkable survivors make a good deal of effort. They dare to hope, they seek out good information, they rally support, and they put good intentions into action. Then they persevere. They deal with the ups and downs. They learn from what others might judge to be mistakes, are prepared to experiment, try new things, and in doing so, develop an inner confidence. They learn through their process, often see it as a journey and commonly come to enjoy the challenge and reflect warmly on their achievements. And in all probability, they have a little good luck as well!

Recovering against the odds is not a casual business. It takes focus, energy and commitment. What then is the main thing to focus upon? Clearly if conventional medicine has said it cannot cure you, it is not that. In my view TM or CAM therapies cannot do it reliably either. The focus in this situation needs to be on inner healing, and to support this inner healing with the best of what conventional medicine, TM and CAM have to offer. Maybe more surgery or chemotherapy is useful to minimize the amount of cancer your body needs to attend to. Maybe you use medical, TM or CAM treatments to boost your immunity and your healing capacity, or to minimize symptoms. But in the situation where no medical cure is on offer, you may be wise to focus on your potential, the lifestyle medicine as we call it, and support that with all else.

How to Combine the Best of What is Available • A Summary

When Curative Treatment Is a Real Prospect

Focus on the medical treatment, and support that with all the other options available to you. Lifestyle medicine will always be useful; use TM and CAM judiciously.

When No Curative Conventional Medical Cure Is on Offer

The choices are

i) Palliative care—accept the diagnosis and the prognosis, and plan for a good death. Lifestyle medicine is likely to be of great benefit for extending life as well as preparing for a good death. Use conventional medical treatments and CAM judiciously.

ii) Living with cancer—accept the diagnosis and the prognosis, then accept that your real goal is to live as long as possible, as well as possible. Quality of life becomes the focus—along with whatever is likely to extend your life. So again, the lifestyle factors set out in this book warrant being the focus of your plans, supported by good medicine and whatever TM and CAM therapies may be helpful.

iii) Accept the diagnosis and reject the prognosis. Dare to recover. Focus on developing healing within by employing lifestyle medicine—and support that with all else. Use conventional medicine, TM and CAM judiciously.

What Specific Treatments Will You Accept? How to Decide What to do

Before we examine in detail how to activate the healer within, let us pause to investigate what external forms of treatment, if any, to which you will be wise to commit. Let us begin with the medical options.

The logical way to assess any proposed form of medical treatment would be to ask your doctor the following questions:

(a) What does the future hold for you if no treatment is given, and in such circumstances what range of life expectancy would you have? The best way to ask this question is statistically. Ask if there were one hundred patients just like you and they had no treatment, what would be a reasonable estimate for the following:

i) How many people would be alive after one year and what would their health be like?

ii) How many people would be alive after five years and what would their health be like?

(b) What range of life expectancy would you have if given the proposed form of treatment? Again, ask for the answer to this question in statistical terms. If there were one hundred people like you who had the same condition and they received the proposed treatment, what would be a reasonable estimate for the following: