Полная версия

When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long Term Capital Management

ROGER LOWENSTEIN

WHEN GENIUS FAILED

The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management

Copyright

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2001

Copyright © Roger Lowenstein 2001

Roger Lowenstein asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9781841155043

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2013 ISBN: 9780007375790

Version: 2018-07-31

Dedication

To Maury Lasky and Jane Ruth Mairs

Epigraph

Past may be prologue, but which past?

–HENRY HU

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

THE RISE OF LONG-TERM CAPITAL MANAGEMENT

1 Meriwether

2 Hedge Fund

3 On the Run

4 Dear Investors

5 Tug-of-War

6 A Nobel Prize

THE FALL OF LONG-TERM CAPITAL MANAGEMENT

7 Bank of Volatility

8 The Fall

9 The Human Factor

10 At the Fed

Epilogue

Notes

Index

Author’s Note and Acknowledgments

About the Author

Other Works

About the Publisher

Introduction

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York is perched in a gray sandstone slab in the heart of Wall Street. Though a city landmark building constructed in 1924, the bank is a muted, almost unseen presence among its lively, entrepreneurial neighbors. The area is dotted with discount stores and luncheonettes—and, almost everywhere, brokerage firms and banks. The Fed’s immediate neighbors include a shoe repair stand and a teriyaki house, and also Chase Manhattan Bank; J. P. Morgan is a few blocks away. A bit farther to the west, Merrill Lynch, the people’s brokerage, gazes at the Hudson River, across which lie the rest of America and most of Merrill’s customers. The bank skyscrapers project an open, accommodative air, but the Fed building, a Florentine Renaissance showpiece, is distinctly forbidding. Its arched windows are encased in metal grille, and its main entrance, on Liberty Street, is guarded by a row of black cast-iron sentries.

The New York Fed is only a spoke, though the most important spoke, in the U.S. Federal Reserve System, America’s central bank. Because of the New York Fed’s proximity to Wall Street, it acts as the eyes and ears into markets for the bank’s governing board, in Washington, which is run by the oracular Alan Greenspan. William J. McDonough, the beefy president of the New York Fed, talks to bankers and traders often. McDonough wants to be kept abreast of the gossip that traders share with one another. He especially wants to hear about anything that might upset markets or, in the extreme, the financial system. But McDonough tries to stay in the background. The Fed has always been a controversial regulator—a servant of the people that is elbow to elbow with Wall Street, a cloistered agency amid the democratic chaos of markets. For McDonough to intervene, even in a small way, would take a crisis, perhaps a war. And in the first days of the autumn of 1998, McDonough did intervene—and not in a small way.

The source of the trouble seemed so small, so laughably remote, as to be insignificant. But isn’t it always that way? A load of tea is dumped into a harbor, an archduke is shot, and suddenly a tinderbox is lit, a crisis erupts, and the world is different. In this case, the shot was Long-Term Capital Management, a private investment partnership with its headquarters in Greenwich, Connecticut, a posh suburb some forty miles from Wall Street. LTCM managed money for only one hundred investors; it employed not quite two hundred people, and surely not one American in a hundred had ever heard of it. Indeed, five years earlier, LTCM had not even existed.

But on the Wednesday afternoon of September 23, 1998, Long-Term did not seem small. On account of a crisis at LTCM, McDonough had summoned—“invited,” in the Fed’s restrained idiom—the heads of every major Wall Street bank. For the first time, the chiefs of Bankers Trust, Bear Stearns, Chase Manhattan, Goldman Sachs, J. P. Morgan, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley Dean Witter, and Salomon Smith Barney gathered under the oil portraits in the Fed’s tenth-floor boardroom—not to bail out a Latin American nation but to consider a rescue of one of their own. The chairman of the New York Stock Exchange joined them, as did representatives from major European banks. Unaccustomed to hosting such a large gathering, the Fed did not have enough leather-backed chairs to go around, so the chief executives had to squeeze into folding metal seats.

Although McDonough was a public official, the meeting was secret. As far as the public knew, America was in the salad days of one of history’s great bull markets, although recently, as in many previous autumns, it had seen some backsliding. Since mid-August, when Russia had defaulted on its ruble debt, the global bond markets in particular had been highly unsettled. But that wasn’t why McDonough had called the bankers.

Long-Term, a bond-trading firm, was on the brink of failing. The fund was run by John W. Meriwether, formerly a well-known trader at Salomon Brothers. Meriwether, a congenial though cautious midwesterner, had been popular among the bankers. It was because of him, mainly, that the bankers had agreed to give financing to Long-Term—and had agreed on highly generous terms. But Meriwether was only the public face of Long-Term. The heart of the fund was a group of brainy, Ph.D.-certified arbitrageurs. Many of them had been professors. Two had won the Nobel Prize. All of them were very smart. And they knew they were very smart.

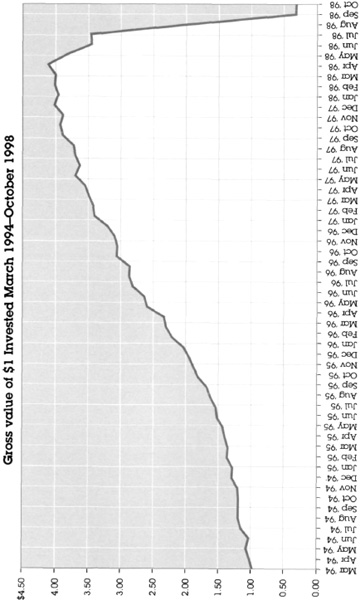

For four years, Long-Term had been the envy of Wall Street. The fund had racked up returns of more than 40 percent a year, with no losing stretches, no volatility, seemingly no risk at all. Its intellectual supermen had apparently been able to reduce an uncertain world to rigorous, cold-blooded odds—on form, they were the very best that modern finance had to offer.

This one obscure arbitrage fund had amassed an amazing $100 billion in assets, virtually all of it borrowed—borrowed, that is, from the bankers at McDonough’s table. As monstrous as this indebtedness was, it was by no means the worst of Long-Term’s problems. The fund had entered into thousands of derivative contracts, which had endlessly intertwined it with every bank on Wall Street. These contracts, essentially side bets on market prices, covered an astronomical sum—more than $1 trillion worth of exposure.

If Long-Term defaulted, all of the banks in the room would be left holding one side of a contract for which the other side no longer existed. In other words, they would be exposed to tremendous—and untenable—risks. Undoubtedly, there would be a frenzy as every bank rushed to escape its now one-sided obligations and tried to sell its collateral from Long-Term.

Panics are as old as markets, but derivatives were relatively new. Regulators had worried about the potential risks of these inventive new securities, which linked the country’s financial institutions in a complex chain of reciprocal obligations. Officials had wondered what would happen if one big link in the chain should fail. McDonough feared that the markets would stop working; that trading would cease; that the system itself would come crashing down.

James Cayne, the cigar-chomping chief executive of Bear Stearns, had been vowing that he would stop clearing Long-Term’s trades—which would put it out of business—if the fund’s available cash fell below $500 million. At the start of the year, that would have seemed remote, for Long-Term’s capital had been $4.7 billion. But during the past five weeks, or since Russia’s default, Long-Term had suffered numbing losses—day after day after day. Its capital was down to the minimum. Cayne didn’t think it would survive another day.

The fund had already asked Warren Buffett for money. It had gone to George Soros. It had gone to Merrill Lynch. One by one, it had asked every bank it could think of. Now it had no place left to go. That was why, like a godfather summoning rival and potentially warring families, McDonough had invited the bankers. If each one moved to unload bonds individually, the result could be a worldwide panic. If they acted in concert, perhaps a catastrophe could be avoided. Although McDonough didn’t say so, he wanted the banks to invest $4 billion and rescue the fund. He wanted them to do it right then—tomorrow would be too late.

But the bankers felt that Long-Term had already caused them more than enough trouble. Long-Term’s secretive, close-knit mathematicians had treated everyone else on Wall Street with utter disdain. Merrill Lynch, the firm that had brought Long-Term into being, had long tried to establish a profitable, mutually rewarding relationship with the fund. So had many other banks. But Long-Term had spurned them. The professors had been willing to trade on their terms and only on theirs—not to meet the banks halfway. The bankers did not like it that the once haughty Long-Term was pleading for their help.

And the bankers themselves were hurting from the turmoil that Long-Term had helped to unleash. Goldman Sachs’s CEO, Jon Corzine, was facing a revolt by his partners, who were horrified by Goldman’s recent trading losses and who, unlike Corzine, did not want to use their diminishing capital to help a competitor. Sanford I. Weill, chairman of Travelers/Salomon Smith Barney, had suffered big losses, too. Weill was worried that the losses would jeopardize his company’s pending merger with Citicorp, which Weill saw as the crowning gem to his lustrous career. He had recently shuttered his own arbitrage unit—which, years earlier, had been the launching pad for Meriwether’s career—and was not keen to bail out another one.

As McDonough looked around the table, every one of his guests was in greater or lesser trouble, many of them directly on account of Long-Term. The value of the bankers’ stocks had fallen precipitously. The bankers were afraid, as was McDonough, that the global storm that had begun, so innocently, with devaluations in Asia, and had spread to Russia, Brazil, and now to Long-Term Capital, would envelop all of Wall Street.

Richard Fuld, chairman of Lehman Brothers, was fighting off rumors that his company was on the verge of failing due to its supposed overexposure to Long-Term. David Solo, who represented the giant Swiss bank Union Bank of Switzerland, thought his bank was already in far too deeply; it had foolishly invested in Long-Term and had suffered titanic losses. Thomas Labrecque’s Chase Manhattan had sponsored a loan to the hedge fund of $500 million; before Labrecque thought about investing more, he wanted that loan repaid.

David Komansky, the portly Merrill chairman, was worried most of all. In a matter of two months, Merrill’s stock had fallen by half—$19 billion of its market value had simply melted away. Merrill had suffered shocking bond-trading losses, too. Now its own credit rating was at risk.

Komansky, who personally had invested almost $1 million in the fund, was terrified of the chaos that would result if Long-Term collapsed. But he knew how much antipathy there was in the room toward Long-Term. He thought the odds of getting the bankers to agree were long at best.

Komansky recognized that Cayne, the maverick Bear Stearns chief executive, would be a pivotal player. Bear, which cleared Long-Term’s trades, knew the guts of the hedge fund better than any other firm. As the other bankers nervously shifted in their seats, Herbert Allison, Komansky’s number two, asked Cayne where he stood.

Cayne stated his position clearly: Bear Stearns would not invest a nickel in Long-Term Capital.

For a moment the bankers, the cream of Wall Street, were silent. And then the room exploded.

1 MERIWETHER

IF THERE WAS one article of faith that John Meriwether discovered at Salomon Brothers, it was to ride your losses until they turned into gains. It is possible to pinpoint the moment of Meriwether’s revelation. In 1979, a securities dealer named J. F. Eckstein & Co. was on the brink of failing. A panicked Eckstein went to Salomon and met with a group that included several of Salomon’s partners and also Meriwether, then a cherub-faced trader of thirty-one. “I got a great trade, but I can’t stay in it,” Eckstein pleaded with them. “How about buying me out?”

The situation was this: Eckstein traded in Treasury bill futures—which, as the name suggests, are contracts that provide for the delivery of U.S. Treasury bills, at a fixed price in the future. They often traded at a slight discount to the price of the actual, underlying bills. In a classic bit of arbitrage, Eckstein would buy the futures, sell the bills, and then wait for the two prices to converge. Since most people would pay about the same to own a bill in the proximate future as they would to own it now, it was reasonable to think that the prices would converge. And there was a bit of magic in the trade, which was the secret of Eckstein’s business, of Long-Term Capital’s future business, and indeed of every arbitrageur who has ever plied the trade. Eckstein didn’t know whether the two securities’ prices would go up or down, and Eckstein didn’t care. All that mattered to him was how the two prices would change relative to each other.

By buying the bill futures and shorting (that is, betting on a decline in the prices of) the actual bills, Eckstein really had two bets going, each in opposite directions.* Depending on whether prices moved up or down, he would expect to make money on one trade and lose it on the other. But as long as the cheaper asset—the futures—rose by a little more (or fell by a little less) than did the bills, Eckstein’s profit on his winning trade would be greater than his loss on the other side. This is the basic idea of arbitrage.

Eckstein had made this bet many times, typically with success. As he made more money, he gradually raised his stake. For some reason, in June 1979, the normal pattern was reversed: futures got more expensive than bills. Confident that the customary relationship would reassert itself, Eckstein put on a very big trade. But instead of converging, the gap widened even further. Eckstein was hit with massive margin calls and became desperate to sell.

Meriwether, as it had happened, had recently set up a bond-arbitrage group within Salomon. He instantly saw that Eckstein’s trade made sense, because sooner or later, the prices should converge. But in the meantime, Salomon would be risking tens of millions of its capital, which totaled only about $200 million. The partners were nervous but agreed to take over Eckstein’s position. For the next couple of weeks, the spread continued to widen, and Salomon suffered a serious loss. The firm’s capital account used to be scribbled in a little book, left outside the office of a partner named Allan Fine, and each afternoon the partners would nervously tiptoe over to Fine’s to see how much they had lost. Meriwether coolly insisted that they would come out ahead. “We better,” John Gutfreund, the managing partner, told him, “or you’ll be fired.”

The prices did converge, and Salomon made a bundle. Hardly anyone traded financial futures then, but Meriwether understood them. He was promoted to partner the very next year. More important, his little section, the inauspiciously titled Domestic Fixed Income Arbitrage Group, now had carte blanche to do spread trades with Salomon’s capital. Meriwether, in fact, had found his life’s work.

Born in 1947, Meriwether had grown up in the Rosemoor section of Roseland on the South Side of Chicago, a Democratic, Irish Catholic stronghold of Mayor Richard Daley. He was one of three children but part of a larger extended family, including four cousins across an alleyway. In reality, the entire neighborhood was family. Meriwether knew virtually everyone in the area, a self-contained world that revolved around the basketball lot, soda shop, and parish. It was bordered to the east by the tracks of the Illinois Central Railroad and to the north by a red board fence, beyond which lay a no-man’s-land of train yards and factories. If it wasn’t a poor neighborhood, it certainly wasn’t rich. Meriwether’s father was an accountant; his mother worked for the Board of Education. Both parents were strict. The Meriwethers lived in a smallish, cinnamon-brick house with a trim lawn and tidy garden, much as most of their neighbors did. Everyone sent their children to parochial schools (the few who didn’t were ostracized as “publics”). Meriwether, attired in a pale blue shirt and dark blue tie, attended St. John de la Salle Elementary and later Mendel Catholic High School, taught by Augustinian priests. Discipline was harsh. The boys were rapped with a ruler or, in the extreme, made to kneel on their knuckles for an entire class. Educated in such a Joycean regime, Meriwether grew up accustomed to a pervasive sense of order. As one of Meriwether’s friends, a barber’s son, recalled, “We were afraid to goof around at [elementary] school because the nuns would punish you for life and you’d be sent to Hell.” As for their mortal destination, it was said, only half in jest, that the young men of Rosemoor had three choices: go to college, become a cop, or go to jail. Meriwether had no doubt about his own choice, nor did any of his peers.

A popular, bright student, he was seemingly headed for success. He qualified for the National Honor Society, scoring especially high marks in mathematics—an indispensable subject for a bond trader. Perhaps the orderliness of mathematics appealed to him. He was ever guided by a sense of restraint, as if to step out of bounds would invite the ruler’s slap. Although Meriwether had a bit of a mouth on him, as one chum recalled, he never got into serious trouble.1 Private with his feelings, he kept any reckless impulse strictly under wraps and cloaked his drive behind a comely reserve. He was clever but not a prodigy, well liked but not a standout. He was, indeed, average enough in a neighborhood and time in which it would have been hell to have been anything but average.

Meriwether also liked to gamble, but only when the odds were sufficiently in his favor to give him an edge. Gambling, indeed, was a field in which his cautious approach to risk-taking could be applied to his advantage. He learned to bet on horses and also to play blackjack, the latter courtesy of a card-playing grandma. Parlaying an innate sense of the odds, he would bet on the Chicago Cubs, but not until he got the weather report so he knew how the winds would be blowing at Wrigley Field.2 His first foray into investments was at age twelve or so, but it would be wrong to suggest that it occurred to any of his peers, or even to Meriwether himself, that this modestly built, chestnut-haired boy was a Horatio Alger hero destined for glory on Wall Street. “John and his older brother made money in high school buying stocks,” his mother recalled decades later. “His father advised him.” And that was that.

Meriwether made his escape from Rosemoor by means of a singular passion: not investing but golf. From an early age, he had haunted the courses at public parks, an unusual pastime for a Rosemoor boy. He was a standout member of the Mendel school team and twice won the Chicago Suburban Catholic League golf tournament. He also caddied at the Flossmoor Country Club, which involved a significant train or bus ride south of the city. The superintendents at Flossmoor took a shine to the earnest, likable young man and let him caddy for the richest players—a lucrative privilege. One of the members tabbed him for a Chick Evans scholarship, named for an early-twentieth-century golfer who had had the happy idea of endowing a college scholarship for caddies. Meriwether picked Northwestern University, in Evanston, Illinois, on the chilly waters of Lake Michigan, twenty-five miles and a world away from Rosemoor. His life story up to then had highlighted two rather conflicting verities. The first was the sense of well-being to be derived from fitting into a group such as a neighborhood or church: from religiously adhering to its values and rites. Order and custom were virtues in themselves. But second, Meriwether had learned, it paid to develop an edge—a low handicap at a game that nobody else on the block even played.

After Northwestern, he taught high school math for a year, then went to the University of Chicago for a business degree, where a grain farmer’s son named Jon Corzine (later Meriwether’s rival on Wall Street) was one of his classmates. Meriwether worked his way through business school as an analyst at CNA Financial Corporation, and graduated in 1973. The next year, Meriwether, now a sturdily built twenty-seven-year-old with beguiling eyes and round, dimpled cheeks, was hired by Salomon. It was still a small firm, but it was in the center of great changes that were convulsing bond markets everywhere.

Until the mid-1960s, bond trading had been a dull sport. An investor bought bonds, often from the trust department of his local bank, for steady income, and as long as the bonds didn’t default, he was generally happy with his purchase, if indeed he gave it any further thought. Few investors actively traded bonds, and the notion of managing a bond portfolio to achieve a higher return than the next guy or, say, to beat a benchmark index, was totally foreign. That was a good thing, because no such index existed. The reigning bond guru was Salomon’s own Sidney Homer, a Harvard-educated classicist, distant relative of the painter Winslow Homer, and son of a Metropolitan Opera soprano. Homer, author of the massive tome A History of Interest Rates: 2000 BC to the Present, was a gentleman scholar—a breed on Wall Street that was shortly to disappear.

Homer’s markets, at least in contrast to those of today, were characterized by fixed relationships: fixed currencies, regulated interest rates, and a fixed gold price ($35 an ounce). But the epidemic of inflation that infected the West in the late 1960s destroyed this cozy world forever. As inflation rose, so did interest rates, and those gilt-edged bonds, bought when a 4 percent rate seemed attractive, lost half their value or more. In 1971, the United States freed the gold price; then the Arabs embargoed oil. If bondholders still harbored any illusion of stability, the bankruptcy of the Penn Central Railroad, which was widely owned by blue-chip accounts, wrecked the illusion forever. Bond investors, most of them knee-deep in losses, were no longer comfortable standing pat. Gradually, governments around the globe were forced to drop their restrictions on interest rates and on currencies. The world of fixed relationships was dead.