Полная версия

To Catch A King: Charles II's Great Escape

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © Charles Spencer 2017

Charles Spencer asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover illustration Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

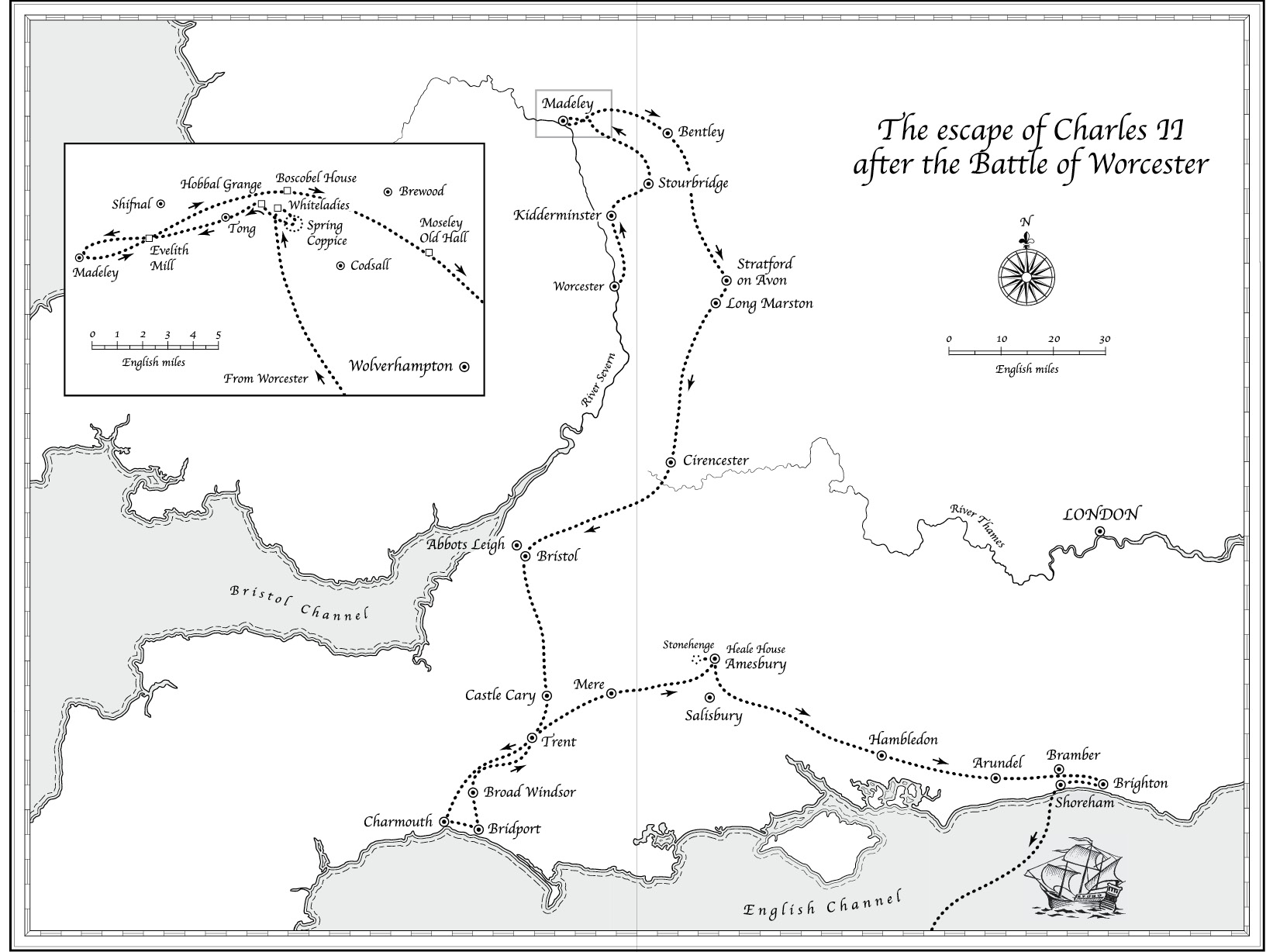

Map by John Gilkes

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008153632

Ebook Edition © October 2017 ISBN: 9780008153656

Version: 2018-10-01

Dedication

For Karen

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Map

Introduction

PART ONE: KING OF SCOTLAND

1 Civil Warrior

2 Royal Prey

3 A Question of Conscience

4 The Crown, Without Glory

5 A Foreign Invasion

6 The Battle of Worcester

7 The Hunt Begins

PART TWO: THE ROMAN CATHOLIC UNDERGROUND

8 Whiteladies

9 The London Road

10 Near Misses

11 Reunion

PART THREE: A LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN

12 Heading for the Coast

13 Processing the Prisoners

14 Touching Distance

15 Still Searching for a Ship

16 Surprise Ending

PART FOUR: REACTION, REWARDS AND REDEMPTION

17 Reaction

18 Rewards

19 Redemption

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Also by Charles Spencer

About the Author

About the Publisher

Epigraph

I know how men in exile feed on dreams.

Aeschylus

Introduction

King Charles II had a favourite story. It was about the six weeks when, aged twenty-one, he had been on the run for his life. Those hunting him down had included the regicides – those responsible for his father’s trial and beheading – who feared him as a deadly avenger; the Parliamentary army, who viewed him as the commander of a defeated, foreign, invasion; and ordinary people, because upon his head sat not the English crown of his birthright, but a colossal financial reward.

This brief period of Charles II’s life stood alone for many reasons. While there were many other times when the bleak reality of his situation fell well short of any reasonable princely expectations, it marked the low point of his fortunes, both as man and royal dignitary. It was uniquely exhilarating for him, in a way that only a genuine life-or-death tussle could be. And it showed off personal qualities that were not always evident in an individual whose self-indulgence and sense of entitlement could infuriate even his most loyal devotees. In his hour of greatest danger, he was proud to note, had arisen within him a quickness of wit, an adaptability, and a hard instinct for survival, that had saved his neck.

In the spring of 1660 Charles returned to England, to claim his throne, on a ship whose figurehead of Oliver Cromwell had hastily been removed, and whose name had been changed from the Naseby (the battle that had been his father’s most punishing defeat) to the Royal Charles. Samuel Pepys was a fellow passenger, and wrote in his diary for 23 May 1660 of how: ‘Upon the quarterdeck he [Charles] fell into discourse of his escape from Worcester, where it made me ready to weep to hear the stories that he told of his difficulties that he had passed through, of his travelling four days and three nights on foot, every step up to his knees in dirt, with nothing but a green coat and a pair of country breeches on, and a pair of country shoes that made him so sore all over his feet, that he could barely stir.’

In the subjects of the kingdom that he had been allowed suddenly and unexpectedly to gain, Charles had found a fresh audience for his pet tale. They would hear repeatedly of their new young king’s exploits. Not that Pepys complained, for the retelling of events that had taken place when he had been a young man of eighteen, six months into his first year at Cambridge University, particularly intrigued him. They awoke, in this most famous of English diarists, the tracking instincts of an investigative journalist. He decided to check how much of the king’s recollections of the six weeks’ adventure were true, and to what extent they had been seasoned by royal fancy, or compromised by forgetfulness.

Two decades later, during one of the royal court’s stays in Suffolk for the horse-racing on Newmarket Heath, Pepys managed to obtain an audience with the king. In his scratchy shorthand (his eyesight had been failing for more than a decade) he took down what Charles remembered of the most electrifying time of his life. Riveted by what he had heard, Pepys quickly secured a second session, his manuscript revealing additions where he included fresh details that Charles had forgotten the first time round.

Meanwhile Pepys resolved to trace those still alive from the motley bunch that had helped the king on his journey from shattering defeat to miraculous delivery. An exceptionally busy man, being at different times a Member of Parliament for two constituencies, and Chief Secretary to the Admiralty, Pepys had hoped to piece together the whole, correct, version of the astonishing tale of escape, and present it as the definitive account. It appears that he had completed almost his entire collection of relevant documents by December 1684, two months before Charles’s sudden death at the age of fifty-four, for that was when he had it bound. A few additions were kept with this volume, including Colonel George Gunter’s report, which arrived at some point during the first seven months of 1685.

There is a paragraph, near the start of Colonel Gunter’s offering, which underlines the way in which those intimately involved in Charles’s escape attempt felt they had been chosen, for whatever reason, to be participants in an event whose eventual outcome had been determined by God. Gunter wrote:

Here, before I proceed in the story, the reader will give me leave to put him in mind, that we write not an ordinary story, where the reader, engaged by no other interest than curiosity, may soon be cloyed with circumstances which signify no more unto him but that the author was at good leisure and was very confident of his reader’s patience. In the relation of miracles, every petty circumstance is material and may afford to the judicious reader matter of good speculation: of such a miracle especially, where the restoration of no less than three kingdoms, and his own particular safety and liberty (if a good and faithful subject) was at the stake.1

Pepys was not in awe of royalty to anything like the same degree as Colonel Gunter. He had been in the crowd at the beheading of Charles I on 30 January 1649, and it is clear that he had some sympathy with the ruthless Parliamentary justice meted out that day. During his time as a naval administrator he never shirked from locking horns with Royalists if, in his view, they were holding back the progress of the service. His disagreements with Prince Rupert of the Rhine, the poster boy of the Crown’s cause in his youth, and Lord Admiral of England in middle age, show a lack of deference to those of the highest birth if he judged them to be wrongheaded, and therefore dangerous to the nation. Pepys was a loyal patriot, but not a fawning one. He therefore makes for an appealing midwife in the delivery of the king’s tale.

There was a great appetite for this unique royal story during the king’s lifetime, even amongst his most intimate circle. James, Duke of York, wrote to Pepys in the middle of 1681, saying he wanted to read for himself his elder brother’s description of his time on the run after the defeat at Worcester. It was his second time of asking this favour of Pepys. Even though the duke promised not to take a copy of the account, Pepys dared to set out that this was a journalistic project that was still very much in progress, and one that he felt especially protective of: ‘My covetousness of rendering it as perfect, as the memory of any of the survivors (interested in any part of that memorable story) can enable me to make it,’ he wrote, ‘has led me into so many and distant enquiries relating thereto, as have kept me out of a capacity of putting it together as I would, and it ought, and shall be, so soon as ever I possess myself of all the memorials I am in expectation of concerning it. Which I shall also (for your Royal Highness’s satisfaction) use my utmost industry in the hastening.’2

He eventually sent the transcript to the duke, while mentioning that he was still awaiting the key testimony of Father John Huddleston, a Roman Catholic priest who had taken a prominent role in the tale of royal derring-do. Pepys received this in March 1682 from Lady Mary Tuke, a lady-in-waiting to the queen, who forwarded it to him on Huddleston’s behalf.

Pepys died in 1703, never having completed his task of stitching together the threads that he had gathered together so painstakingly. Perhaps the death of the central figure in the tale made the undertaking one that seemed less pressing.

Whatever the reason, the testimonies he had assembled, and which he left behind in one place, are invaluable to those that have followed. Indeed, the accounts of Charles II himself, as well as those of Father Huddleston, Thomas Whitgreave and Colonel Phillips, are priceless testimonies to a factual tale that reads like fiction. All four have long been recognised as the key first-hand records of one of the greatest escapes in history.

Thomas Blount provided another sparkling contemporary account of the getaway. Blount was a Roman Catholic, and a Royalist, who gloried in the miracle of the tale, and so might have been tempted by his predispositions to stray from the truth. But he was also a lexicographer and an antiquarian, who studied law. His intellectual discipline, when compiling dictionaries of obscure words or studying the distant past, set a standard for his painstaking research in this field of recent royal history. In his introduction to Boscobel Blount assured his readers: ‘I am so far from that foul crime of publishing what’s false, that I can safely say I know not one line unauthentic; such has been my care to be sure of the truth, that I have diligently collected the particulars from most of their mouths, who were the very actors in this scene of miracles.’

Nearly all of Blount’s sources were still alive at the time of Boscobel’s completion. Far from disputing his version of events, they were happy to contribute further recollections, which he included in his next edition. It seems that he accurately assembled the memories of his interviewees, many of whom had little or no literacy. They were relying on Blount to disperse their experiences to his readers.

How best to use such remarkable sources? Unlike the king’s version of what had happened during the six weeks, the other contributors, of course, concentrated on what they remembered from their own few days or so in the core of the narrative. It is obvious that nothing else in their lives came close to the excitement of being involved in their king’s survival. As a result, extraordinary details are remembered – the opening of a bottle of sherry releasing two hornets from its neck; the way the king cooked his collops of lamb; the sight of his battered and bloody feet.

Equally understandable would be the embellishment of tales over time, and the exaggeration of services rendered. I have weighed up the likelihood of things happening as recalled, the closeness of the witness to the action, and the inevitability of human foibles clouding the picture, as best I can. There remains one imponderable, which I try to deal with even-handedly: the competing accounts of Captain Alford and William Ellesdon as to what upended the escape attempt at Charmouth. At least one of them has to be lying, but both had supporting witnesses, so it is hard to draw a conclusion either way.

Charles II himself’s memory of events seems to have been accurate, the day-to-day order of events apparently seared into his mind. For a man of hearty appetites, the recall of when and if he was fed, and what with, seems to have been a perpetual concern: when he first spoke to Pepys, he was feasting on pease-pudding, and two different types of roast meat. On the other hand, Charles chose not to deal with fears, or other emotions, in his account. This is a great shame for the modern reader. Perhaps admitting to what might, in the late seventeenth century, have been perceived as weaknesses, was considered a little much.

Those mistakes that Charles makes in his recollections seem to me to be understandably human: he was, for instance, wrong to think that one of his collaborators, Thomas Whitgreave, had the surname of ‘Pitchcross’, or ‘Pitchcroft’. That was, in fact, the name of the field to the north of Worcester where the Royalist troops had mustered before the dismal defeat that brought about his need to run. If anything, such an error simply suggests that Charles’s recollections came direct from his memory, rather than from written notes.

Intriguingly rich sources aside, I have also sought, more than many others who have written on this subject before me, to set the narrative in its wider context. The battle of Worcester is pretty much forgotten, even in England. This is something that two future American presidents, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, condemned when they insisted on visiting the battlefield in 1786. Adams wrote:

Worcester were curious and interesting to us, as scenes where freemen had fought for their rights. The people in the neighbourhood, appeared so ignorant and careless at Worcester that I was provoked and asked, ‘And do Englishmen so soon forget the ground where Liberty was fought for? Tell your neighbours and your children that this is holy ground, much holier than that on which your churches stand. All England should come in Pilgrimage to this Hill, once a Year.’

Adams had, I believe, a point.

In England we may pass one of the more than 400 pubs called the Royal Oak, and be briefly reminded of the most lyrical part of this tale. But my conclusion at the end of writing this book is that Charles’s escape attempt was not some jolly adventure, but a deadly serious race against an enemy eager to spill fresh Stuart blood on an executioner’s block.

In the final analysis, this is a tale of grit, of loyalty, and of luck.

PART ONE

1

Civil Warrior

Now all such calamities as may be avoided by human industry arise from war, but chiefly from civil war, for from this proceed slaughter, solitude, and the want of all things.

Thomas Hobbes, ‘De Corpore’, 1655

Charles, Prince of Wales, witnessed the English Civil War up close from its outbreak till its end. He was present at the battle of Edgehill, in October 1642. This was the first major engagement of a conflict that erupted over differences between the Crown and Parliament, concerning the limits of the king’s power, and clashing religious beliefs. Nine years later he would command an army at Worcester, the final action in the most bloodstained chapter in British history. By that time the Civil Wars in England, Ireland and Scotland had claimed hundreds of thousands of lives in the three kingdoms.

At Edgehill Prince Charles, then a twelve-year-old honorary captain in the King’s Horse Guards, had proved to be a handful. It had been hard to stop him from leading a charge against the rebel cavalry. At another point he and his younger brother James, Duke of York, were nearly captured, and had to take cover in a barn packed with wounded soldiers.

The boys had spent part of that clear autumn afternoon at Edgehill in the care of their father’s elderly physician, Dr William Harvey, the English authority on anatomy. It was Harvey who had, in 1628, been the first to write about the circulation of blood in the body. The distinguished doctor took the pair of princes to shelter under a hedge, where he hoped to divert them from the violent bloodshed taking place all around them by reading a book. This distraction did not go to plan, Harvey telling his biographer John Aubrey that ‘he had not read very long before a bullet of a great gun grazed on the ground near him, which made him remove his station’.1

Despite the dangers, King Charles I remained keen to keep his eldest son by his side during the first two and a half years of the conflict. Towards the end of 1644 he gave the fourteen-year-old prince the title ‘first Captain-General of all our Forces’, although such duties were in reality performed by the king’s nephew, Prince Rupert of the Rhine.

In early 1645, as Parliament began to gain a decisive upper hand in the war, Charles I decided to prevent the possibility of his being caught or killed at the same time as his heir. Keen ‘to unboy’ his son, ‘by putting him into some action, and acquaintance [him] with business out of his own sight’,2 he sent him away to his own, separate, command. The prince was created general of the Royalist forces in the west of England, with real responsibilities. On 5 March 1645 he parted from his father for what would prove to be the last time, riding out of Oxford into a ferocious rainstorm.

With the prince went an escort of 300 cavalrymen. He was safely delivered to Bristol, but it could easily have ended otherwise. On their return journey a large force of Charles’s guards were ambushed near Devizes, in Wiltshire. Forty of them were killed, while twenty officers were among the many captured Cavaliers.

A handful of advisers, hand-picked by the king, rode with Charles to Bristol. Prominent among them was Sir Edward Hyde, who had long been involved in the prince’s life. In early 1642 he had looked after Charles while his French mother, Queen Henrietta Maria, had sailed to the Continent to raise funds and forces for her husband. It was the start of a relationship that would run the gamut of service, trust, disappointment, triumph, rejection and disgrace.

Twenty-one years older than the prince, Hyde was at heart a traditional patriot who believed in political stability. He had hoped for a peaceful resolution to the tensions between Crown and Parliament, believing a compromise was both possible and desirable. But there was too much fear and suspicion on both sides for reason and sense to prevail.

As civil war became increasingly likely, Hyde’s hopes for order gradually turned him from being a critic of Charles I into a Royalist. When the king finally declared war, raising the royal standard at Nottingham in August 1642, Hyde was by his side. After that he lent his fine brain and brilliant oratory to Charles I’s cause. Hyde was made Chancellor of the Exchequer, the king justifying the promotion with a rather downbeat endorsement: ‘The truth is, I can trust nobody else.’3

Hyde found court life complicated. It was hard for him to negotiate a landscape that was pitted with factions, and where insincerity and self-interest were the perpetual themes. Meanwhile a supreme confidence in his own views made it challenging for him to accommodate those of others when they differed.

He brought this inflexible mindset on campaign, when he accompanied Prince Charles as he took up his command in the west. Hyde hoped to bring order to the Crown’s resistance there, but his prickly attitude, perhaps fired up by the raging gout that often dogged him, instead diminished what remained of morale in this corner of England. It was a sphere of the war that was going as poorly for the Crown as any other, not helped by the king’s leading generals in the region being at odds with one another. One, Sir Ralph Hopton, was a man of sobriety and religion, who once refused to join battle until his men had finished hearing divine service. Another, Lord Goring, was remembered even by his fellow Royalists as the epitome of the hard-drinking, roistering Cavalier. A third, Sir Richard Grenville, had been condemned as ‘traitor, rogue, villain’ by Parliament after switching allegiance to the Crown. Grenville, grandson of a great Elizabethan naval hero of the same name, had a violent temper and a reputation for ruthlessness in the field. He refused to serve under Goring or Hopton, and would be imprisoned for his disobedience.

Prince Charles arrived in Bristol in early April to find apathy among the area’s leading Royalists, and plague erupting in the city. He decided to move thirty-two miles south-west to Bridgwater, a town whose castle was believed to be impregnable, and whose governor, Sir Edmund Wyndham, he knew. Sir Edmund’s wife, Christabella, had been Charles’s wet-nurse and assistant governess from when he was one until he turned five.

Christabella Wyndham was noted for her great beauty, and for her bossiness. Samuel Pepys noted in his diary that she ‘governed’ Charles ‘and everything else … as [if she were] a minister of state’.4 Sir Edward Hyde dismissed her as ‘a woman of great rudeness and a country pride’.5 But she had her charms. Christabella, in her late thirties, and Charles, yet to turn fifteen, became lovers during his stay in Bridgwater Castle in 1645. Afterwards, far from exercising discretion, Christabella appalled the prince’s advisers by being shamelessly familiar with him, showering him with kisses in public. When Charles proved unable to concentrate on matters of state, thanks to Christabella’s distracting influence, his advisers moved him on from Bridgwater as quickly as they could.

That summer Parliament’s New Model Army arrived outside Bridgwater in huge numbers, to test its impregnability. Hearing that Oliver Cromwell, the rebel force’s second-in-command, was examining the town’s defences from the far side of its imposing moat, Christabella Wyndham decided to act. As an insult to the enemy, and as a reminder of her previous role as royal wet-nurse, she is reported as having exposed one of her breasts, picked up a loaded musket, and fired. The shot missed Cromwell, but killed his sergeant-at-arms.