Полная версия

Think Like Da Vinci: 7 Easy Steps to Boosting Your Everyday Genius

THINK LIKE DA VINCI

7 EASY STEPS TO BOOSTING YOUR EVERYDAY GENIUS

MICHAEL GELB

Dedication

This book is dedicated tothe Da Vincian Spirit manifested inthe life and work of Charles Dent.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Preface: “Born of the Sun”

Preface to the New Edition

PART ONE

Introduction: Your Brain Is Much Better than You Think

Learning from Leonardo

A Practical Approach to Genius

The Renaissance, Then and Now

The Life of Leonardo da Vinci

Major Accomplishments

PART TWO The Seven Da Vincian Principles

Curiosità

Dimostrazione

Sensazione

Sfumato

Arte/Scienza

Corporalita

Connessione

Conclusion: Leonardo’s Legacy

PART THREE

The Beginner’s da Vinci Drawing Course

Leonardo Da Vinci Chronology: Life and Times

Recommended Reading

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface: “Born of the Sun”

Think of your greatest heroes and heroines, your most inspirational role models. Maybe, if you are very lucky, the list includes your mom or dad. Perhaps you are most inspired by great figures from history. Immersing yourself in the life and work of great artists, leaders, scholars, and spiritual teachers provides rich nourishment for the mind and heart. Chances are, you picked up this book because you recognize Leonardo as an archetype of human potential and you are intrigued by the possibility of a more intimate relationship with him.

When I was a child, Superman and Leonardo da Vinci were my heroes. While the “Man of Steel” fell by the wayside, my fascination with Da Vinci continued to grow. Then, in the spring of 1994, I received an invitation to visit Florence to speak to a prestigious and notoriously demanding association of company presidents. The group chairman asked, “Could you prepare something for our members on how to be more creative and balanced, personally and professionally? Something that will point them in the direction of becoming Renaissance men and women?” In a heartbeat I responded with my dream: “How about something on thinking like Leonardo da Vinci?”

It was not an assignment I could take lightly. My students would already have paid substantial fees to attend the six-day “university,” one of several opportunities the society offers its members each year to meet in the world’s great cities to explore history, culture, and business while pursuing personal and professional development. Given the chance to choose among several concurrent classes – mine was running at the same time as five others, including one taught by former Fiat president Giovanni Agnelli – members were invited to rate each speaker on a scale of one to ten and were encouraged to walk out of any presentation they didn’t like. In other words, if they don’t like you, they chew you up and spit you out!

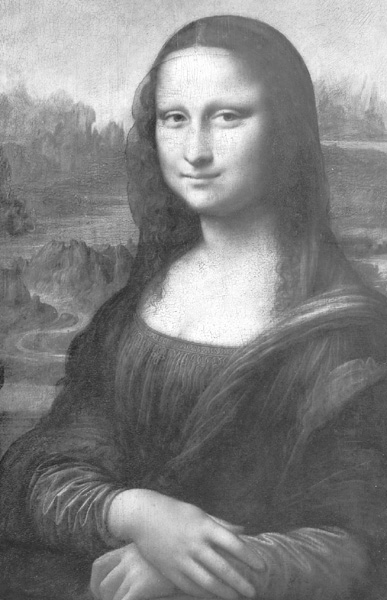

Despite my lifelong fascination with my new topic, I knew I had work to do. In addition to intensive reading, my preparation included a Da Vinci pilgrimage, beginning with a visit to Leonardo’s Portrait of Ginevra De’ Benci at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. In New York, I caught up with the traveling “Codex Leicester” exhibit sponsored by Bill Gates and Microsoft. Then to London to see the manuscripts in the British Museum, The Virgin and Child with St. Anne at the National Gallery, and to the Louvre in Paris to spend a few days with Mona Lisa and St. John the Baptist. The highlight of this pilgrimage, however, was visiting the château of Cloux near Amboise, where Da Vinci spent the last few years of his life. The château is now a Da Vinci museum, with amazing replicas of some of Leonardo’s inventions crafted by engineers from IBM. Walking the grounds that he walked, sitting in his study and standing in his bedroom, looking out his window, seeing the view that he gazed at every day, I felt my heart overflow with awe, reverence, wonder, sadness, and gratitude.

Of course, I went on to visit Florence, where, eventually, I gave my talk to the presidents. The fun began when the person introducing me confused her notes on my biography with the paper I had submitted on Da Vinci. She said – and I am not, to quote Dave Barry, making this up – “Ladies and gentlemen, I am extremely privileged today to introduce to you an individual whose background surpasses anything I have ever encountered: anatomist, architect, botanist, city planner, costume and stage designer, chef, humorist, engineer, equestrian, inventor, geographer, geologist, mathematician, military scientist, musician, painter, philosopher, physicist and raconteur … Ladies and gentlemen, allow me to present … Mr. Michael Gelb!”

Ah, if only …

Well, the talk was a success (no one walked out), and it gave birth to the book you hold in your hands.

Before that unforgettable introduction, one of the members approached me and said, “I don’t believe that anyone can learn to be like Leonardo da Vinci, but I’m going to your lecture anyway.” You may be thinking something similar: Is the premise of this book that every child is born with the capacities and gifts of Leonardo da Vinci? Does the author really believe that we can all be geniuses of Da Vinci’s stature? Well, actually, no. Despite decades devoted to discovering the full scope of human potential and how to awaken it, I side with Da Vinci’s disciple Francesco Melzi, who wrote on the occasion of the maestro’s death: “The loss of such a man is mourned by all, for it is not in the power of Nature to create another.” As I learn more about Da Vinci, my sense of awe and mystery multiplies. All great geniuses are unique, and Leonardo was, perhaps, the greatest of all geniuses.

But the key question remains, Can the fundamentals of Leonardo’s approach to learning and the cultivation of intelligence be abstracted and applied to inspire and guide us toward the realization of our own full potential?

Of course, my answer to this question is: Yes! The essential elements of Leonardo da Vinci’s approach to learning and the cultivation of intelligence are quite clear and can be studied, emulated, and applied.

Is it hubris to imagine that we can learn to be like the greatest of all geniuses? Perhaps. It’s better to think of his example guiding us to be more of what we truly are.

This is a guidebook, inspired by one of history’s great souls, for that journey. An invitation to breathe the vivid air, to feel the fire in your heart’s centre, and the full flowering of your spirit.

Michael J. Gelb

January 1998

Preface to the New Edition

On July 15, 2003, I had the delightful opportunity to speak with the audience at the 2nd Stage Theater in New York City following a sold-out performance of Mary Zimmerman’s brilliant play The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. One of the questions from the audience may reflect something in your mind as you hold this book in your hands: “How can the scope and depth of Leonardo’s genius be understood and why does his influence seem to be growing?”

We can speculate about the origins of Leonardo’s unparalleled genius, but the more we learn about him the more the mystery seems to grow. And so does his influence, even in popular culture. In the opening scene of the major motion picture The Italian Job rapper turned actor Mos Def walks along the canal in Venice reading this book. Def shows it to one of his partners in crime, played by Jason Statham, and explains why Leonardo is so “cool.” The maestro also stars in Dan Brown’s best-selling mystery novel The Da Vinci Code, and makes cameo appearances in various episodes of Star Trek as a holographic adviser to the captain of the Enterprise.

This universal fascination with the supreme man of the Renaissance reflects a more personal, intuitive inkling about our own possibilities for creative expression. Beyond all his stellar achievements, Leonardo da Vinci serves as a global archetype of human potential. Since this book was first published in 1998, it’s been translated into 18 languages and I’ve heard from enthusiasts around the world. A Polish elementary school teacher uses the seven principles to organize her class curriculum. The head of strategy for a major London-based consulting firm discovered that Leonardo was an invaluable ally in helping his multinational clients solve some of their most important business problems. And a 32-year-old father from Tennessee commented, “This book gave me everything I always wanted to teach my children but didn’t have the words to say.”

One of my favorite bits of feedback came from renowned anthropologist, visionary, author and shaman Jean Houston. A modern Renaissance woman, Jean serves as an adviser to world leaders on accessing the essential wisdom of the universal archetypes expressed in diverse cultures and traditions. About a year after Think Like Da Vinci was first published I was invited to speak to a group of 500 psychotherapists in Washington, D.C. After the presentation, Jean, who was also there to address the conference, appeared and whispered in my ear, “Leonardo is very pleased.”

It’s easy to imagine Leonardo’s pleasure when Ricardo Muti conducted Beethoven’s Fifth in tribute to him at La Scala in September of 1999. The celebration took place exactly 500 years after the day when the model for Leonardo da Vinci’s magnificent 24-foot-tall equestrian sculpture was destroyed by invading French troops. Now, the “Lost Horse” was being resurrected in Milan, and after leaving the concert one could almost see the smile in the eyes of the statue of Leonardo which graces the center of the La Scala square.

The rebirth of the Horse began in the imagination of a former airline pilot and art collector, Charles Dent, to whom this book is dedicated. Although he died in 1994, Dent’s work continued through the non-profit organization he founded. Honoring a promise made to Dent on his deathbed, the board of Leonardo da Vinci’s Horse, Inc. led a coalition of donors, artists, metallurgists, volunteers and scholars in fulfilling this dream. Sculpted by Nina Akamu, the majestic Horse stands proudly in Milan with a second full size casting in the Fredrik Meijer Gardens in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Smaller scale bronze replicas also adorn Leonardo’s hometown of Vinci, Italy and the Dent family hometown of Allentown, PA.

The rebirth of this lost masterpiece is a testament not only to the maestro’s artistic genius but also to his embodiment and expression of the human creative spirit. This spirit was also alive in October of 2001 when Queen Sonja of Norway dedicated a bridge linking her country and Sweden. Built based on an original design sketched in 1502 by Leonardo da Vinci, the bridge was originally intended for the Turkish Sultan Bejazet II. But, the Sultan declined to proceed with the project because its revolutionary pressed-bow engineering and 720-foot span seemed “too fantastic.” In 1996, Norwegian artist Vebjørn Sand saw Leonardo’s sketch and, moved by its graceful beauty and powerful symbolism, dreamed of recreating it. After six years of fundraising and testing, in cooperation with the Norwegian Transportation Ministry, Sand’s Leonardo Bridge was unveiled just outside Oslo. Spanning the highway connecting Norway to neighboring Sweden, it is the first civil engineering project in history based on an actual Da Vinci design. Sand imagines a Leonardo Bridge on every continent as a global tribute to the remarkable life and genius of Leonardo da Vinci and his inspiration for all of us to express our own creative potential.

Sand and Dent’s nephew Peter were both present at the opening reception of the amazing exhibition of Da Vinci drawings at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in the spring of 2003. Over flutes of prosecco we shared our reflections on the maestro’s drawings and his vivifying presence. We agreed that if God could draw this is what it might look like. Sand then laughed as he shared the story of one municipal council committee that had declined to proceed with the building of a Leonardo bridge because they felt that the design was “too futuristic.” Dent explained that having helped fulfill his uncle’s vision to create Leonardo’s Horse, his organization was now merging with the Discovery Center of Science and Technology, with a mission to bring Leonardo’s inspiration to science education for children around the world. The Center’s educational mission is expressed in the seven principles for thinking like Leonardo that you will learn in the pages that follow.

One of Leonardo’s favorite images was the rippling circles of water that flow out from the center when a stone is dropped into a pool of water. Leonardo’s life was a gem tossed into a pool of time that became known as the Renaissance and his genius ripples on and on into eternity. The art critic Bernhard Berenson summed it up when he said of Leonardo, “Everything he touched turned to eternal beauty.” My wish for you is that you will allow the principles for thinking like Leonardo to bring a touch of that rippling beauty to your life every day.

Michael J. Gelb

September 2003

Introduction Your Brain Is Much Better than You Think.

Although it is hard to overstate Leonardo da Vinci’s brilliance, recent scientific research reveals that you probably underestimate your own capabilities. You are gifted with virtually unlimited potential for learning and creativity. Ninety-five percent of what we know about the capabilities of the human brain has been learned in the last twenty years. Our schools, universities, and corporations are only beginning to apply this emerging understanding of human potential. Let’s set the stage for learning how to think like Leonardo by considering the contemporary view of intelligence and some results of the investigation into the nature and extent of your brain’s potential.

Most of us grew up with a concept of intelligence based on the traditional IQ test. The IQ test was originated by Alfred Binet (1857–1911) to measure, objectively, comprehension, reasoning, and judgment. Binet was motivated by a powerful enthusiasm for the emerging discipline of psychology and a desire to overcome the cultural and class prejudices of late nineteenth-century France in the assessment of children’s academic potential. Although the traditional concept of IQ was a breakthrough at the time of its formulation, contemporary research shows that it suffers from two significant flaws.

The first flaw is the idea that intelligence is fixed at birth and immutable. Although individuals are endowed genetically with more or less talent in a given area, researchers such as Buzan, Machado, Wenger, and many others have shown that IQ scores can be raised significantly through appropriate training. In a recent statistical review of more than two hundred studies of IQ published in the journal Nature, Bernard Devlin concluded that genes account for no more than 48 percent of IQ. Fifty-two percent is a function of prenatal care, environment, and education.

The second weakness in the commonly held concept of intelligence is the idea that the verbal and mathematical reasoning skills measured by IQ tests (and SATs) are the sine qua nons of intelligence. This narrow view of intelligence has been thoroughly debunked by contemporary psychological research. In his modern classic, Frames of Mind (1983), psychologist Howard Gardner introduced the theory of multiple intelligences, which posits that each of us possesses at least seven measurable intelligences (in later work Gardner and his colleagues catalogued twenty-five different subintelligences). The seven intelligences, and some genius exemplars (other than Leonardo da Vinci, who was a genius in all of these areas) of each one, are:

The theory of multiple intelligences is now accepted widely and when combined with the realization that intelligence can be developed throughout life, offers a powerful inspiration for aspiring Renaissance men and women.

In addition to expanding the understanding of the nature and scope of intelligence, contemporary psychological research has revealed startling truths about the extent of your potential. We can summarize the results with the phrase: Your brain is much better than you think. Appreciating your phenomenal cortical endowment is a marvelous point of departure for a practical study of Da Vincian thinking. Contemplate the following: your brain

What happens to your brain as you get older? Many people assume that mental and physical abilities necessarily decline with age; that we are, after age twenty-five, losing significant brain capacity on a daily basis. Actually, the average brain can improve with age. Our neurons are capable of making increasingly complex new connections throughout our lives. And, our neuronal endowment is so great that, even if we lost a thousand brain cells every day for the rest of our lives, it would still be less than 1 percent of our total (of course, it’s important not to lose the 1 percent that you actually use!).

This last point was established first by Pyotr Anokhin of Moscow University, a student of the legendary psychological pioneer Ivan Pavlov. Anokhin staggered the entire scientific community when he published his research in 1968 demonstrating that the minimum number of potential thought patterns the average brain can make is the number 1 followed by 10.5 million kilometers of typewritten zeros.

Anokhin compared the human brain to “a multidimensional musical instrument that could play an infinite number of musical pieces simultaneously.” He emphasized that each of us is gifted with a birthright of virtually unlimited potential. And he proclaimed that no man or woman, past or present, has fully explored the capacities of the brain. Anokhin would probably agree, however, that Leonardo da Vinci could serve as a most inspiring example for those of us wishing to explore our full capacities.

LEARNING FROM LEONARDO

Baby ducks learn to survive by imitating their mothers. Learning through imitation is fundamental to many species, including humans. As we become adults, we have a unique advantage: we can choose whom and what to imitate. We can also consciously choose new models to replace the ones we outgrow. It makes sense, therefore, to choose the best “role models” to guide and inspire us toward the realization of our potential.

Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) was the original uomo universale and one of Leonardo’s “role models.” Architect, engineer, mathematician, painter, and philosopher, Alberti was also a gifted athlete and musician.

So, if you want to become a better golfer, study Ben Hogan, Jack Nicklaus, and Tiger Woods. If you want to become a leader, study Winston Churchill, Abraham Lincoln, and Queen Elizabeth I. And if you want to be a Renaissance man or woman, study Leon Battista Alberti, Thomas Jefferson, Hildegard von Bingen, and best of all, Leonardo da Vinci.

In The Book of Genius Tony Buzan and Raymond Keene make the world’s first objective attempt to rank the greatest geniuses of history. Rating their subjects in categories including “Originality,” “Versatility,” “Dominance-in-Field,” “Universality-of-Vision,” and “Strength and Energy,” they offer the following as their “top ten.”