Полная версия

Selling Your Father’s Bones: The Epic Fate of the American West

SELLING YOUR FATHER’S BONES

The Epic Fate of the American West

BRIAN SCHOFIELD

CONTENTS

Dedication

Epigraph

List of Illustrations

Prologue

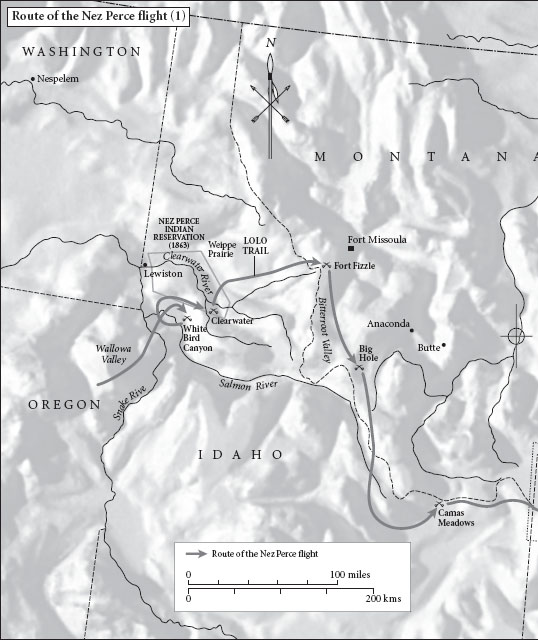

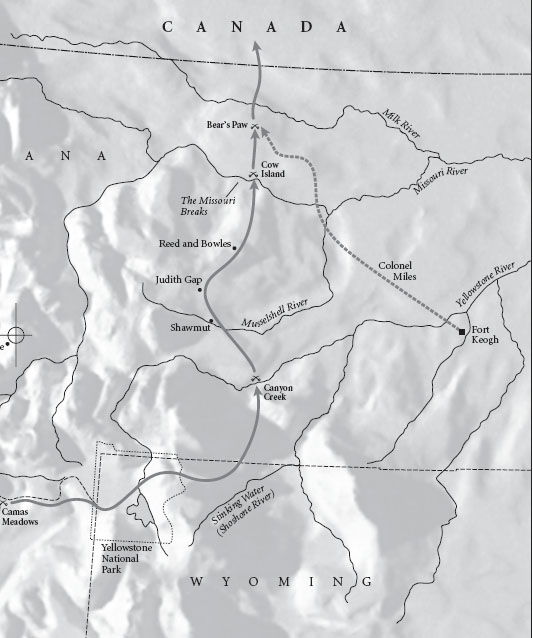

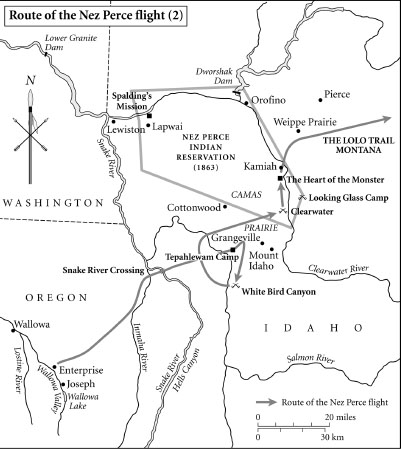

Maps

1 Homeland

2 Settlement

3 Fever

4 Poison

5 Outbreak

6 Unequal War

7 To the Big Hole

8 Survival

9 Crescendo

10 Climax

11 ‘We’re Still Here’

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

Copyright

About the Publisher

DEDICATION

For my grandfather

EPIGRAPH

‘I believe…that sooner or later…somewhere…somehow…we must settle with the world and make payment for what we have taken’

The Lone Ranger’s Creed

Prologue

As THE SUN glowed red across the grassland, a group of children headed away from the village, through the willow trees, to squeeze a few more games from the fading daylight. The boys, mimicking their fathers, played with sticks and bones along the banks of the winding creek, their shrieks fading into the great expanse of the valley — until a chill cut through the air, and it was time to light a fire. The gang gathered wood and huddled close to the flames. Then, as an unfamiliar presence entered the circle of light, they fell to frozen silence. ‘Two men came there wrapped in grey blankets. They stood close, and we saw they were white men.’

The youngsters bolted towards the village in a panic, but when they looked back, the men in the grey blankets had disappeared -and they were soon forgotten as the games began again. Bed-time came, and the children lay down without sharing this unsettling sight with their elders.

That night, the village held a celebration, to mark a day of rest and calm, and good hunting amongst the dense herds of the grasslands. The seven hundred Nez Perce were many miles from home, they’d been travelling for almost two months to reach this riverbank, and they had still further yet to travel — but today, at least, they were at peace, and for that they gave thanks. The warriors paraded through the encampment, singing and drumming in the firelight, their blustering leader encouraging all to relax and enjoy the respite. Elsewhere, a younger chief tended to his own responsibilities, for the young and the old of the camp, the frail and the enfeebled. It was past midnight when the carousing ended, and the valley fell silent.

One hundred and eighty-three United States infantrymen crouched in the darkness and waited. The sleeping village was but a few hundred yards away, the embers of its fires still glowing, while the army shivered on the sloping meadow above, their discipline holding in the bleak, thin night — no cigarettes lit, no rifles dropped, not a sound. Hours passed. The dew soaked easily through the troopers’ threadbare uniforms, tightening the vice of cold. One man struck a match, and was slapped and shushed back into darkness by the soldiers around him.

The sounds of dogs barking and babies crying drifted over the willows and rushes from the dozing village. Just before dawn, a few women emerged from their tepees to refuel the campfires, enjoy a brief gossip and head back to their warm beds. And still the soldiers watched and waited.

At the very first greying of the sky, the troops began to move through the scrubland that lay between the high meadow and the riverbank, crawling and crouching forward, hiding behind the shallow rolls in the earth. A single line of men crept over the sodden ground — then stopped dead. Across the creek, an elderly man had emerged yawning from his lodge, cheerfully accepting that his sleep was complete. Mounting his waiting horse, the elder set off slowly towards the sloping meadow, to check on the village’s grazing herd. His eyes were beginning to wear with time, and he peered into the half-light as his horse forded the creek and strolled through the morning mist — heading straight towards the waiting army.

Fear coursed through the troops as the lone rider wandered closer to their ranks, a hundred yards distance shading to fifty, then thirty, twenty — and still the old man, blessed with a morning to himself, saw no sign of the long, thin line of rifles trained upon him. Ahead, lost in the mist, hearts raced and nerves strained. A cluster of untrained men, callow volunteers, were wound tightest of all — the old man was riding straight for the cleft in the earth where the five lay. He was just ten yards away now. Still he rode on, humming into the lifting gloom. Huddled against the soil, the volunteers heard each footstep approach, battling to summon their courage and keep their senses. The gap closed, and closed, barely five yards now.

The young men, breathless with panic, snapped. Leaping to their feet, they raised their rifles. Across the glistening valley, the deer and the antelope, the buffalo and the coyotes scattered into the distance, away from the echoing crack of gunfire.

MAPS

CHAPTER ONE

HOMELAND

‘These persons inculcate a sanctimonious reverence for the customs of their ancestors; that whatsoever they did, must be done through all time; that reason is a false guide’

THOMAS JEFFERSON, third President of the United States

‘I belong to the earth out of which I came’

TOOHOOLHOOLZOTE, Nez Perce leader

THIS IS HOW the people came to be.

Coyote was helping the salmon swim up the Columbia River, to ensure everyone would have plenty of fish to eat, when he first heard the shouts:

‘Why are you bothering with that? Everyone’s gone, the monster has them.’

The meadowlark told Coyote that everyone had been swallowed by the giant monster, to which he replied, ‘That is where I must go, too.’ He bathed his fur, to ensure he was as tasty as possible, and tied himself to three mountains with long ropes. On his back he put a pack containing five stone knives, some pitch and a fire-making kit. He then walked over the ridge to see the vast body of the monster stretching into the distance, and shouted his challenge: ‘Oh Monster, we are going to inhale each other!’

‘You go first,’ replied the monster, and Coyote breathed in with all his power, trying to swallow the monster, but could only make the beast quiver and shake a little. Next came the monster’s turn, and he breathed in like a roaring wind, lifting Coyote through the air towards him. As he flew, Coyote left camas roots and serviceberry bushes in the ground, saying, ‘We are near the time when the human beings will come, and they will be glad of these.’

Coyote flew into the monster’s mouth, and began walking through its body, past the bones of fallen friends, asking the living for directions to the fiend’s heart. From the shadows, Bear rushed at him, but Coyote shouted, ‘So! You’re only aggressive to me?’ and kicked him on the nose. Then, as he went deeper, Rattlesnake bristled at him: ‘So you are only vicious to me?’ said Coyote, stamping on the snake’s head, flattening it for good.

When he reached the heart, he started a fire with his flint, and smoke began to pour from all the monster’s orifices. ‘Coyote, let me cast you out!’ begged the agonized monster, but the tricky Coyote reminded the fiend that he’d just swallowed a pillar of the local community, with serious responsibilities, who couldn’t be seen to be covered in vomit or phlegm: ‘Oh yes, and let it be said that he who was cast out is officiating in the distribution of salmon!’

‘Well, then leave through my nose.’

‘And will they not say the same?’

‘My ears?’

‘Ha! “Here is earwax officiating in the distribution of food!”’

‘By the back door?’

‘Not a chance.’

By now the monster was writhing in pain. Coyote began to cut away at his heart, breaking first one stone knife on the flesh, then another, then three, four, five. Finally he leapt on the heart and tore it away with his bare hands, killing the beast. In its death throes, the monster opened all its orifices, and everyone ran out, kicking the bones of their dead neighbours ahead of them. The muskrat, unwisely, chose to use the rear exit, and it closed tight on his tail, stripping it of hair forever.

Once everyone was out, Coyote sprinkled the blood of the monster on the bones of the dead, bringing them back to life, then he began to carve up the monster’s flesh, spreading it across the distant lands, towards the sunrise and sunset, the warmth and cold. And wherever the flesh came to rest, there arose the destiny of a people -the Coeur d’Alêne to the north, Cayuse to the west, Crow to the east, the Pend d’Oreille, Salish, Blackfoot, Sioux, until people were destined to cover the wide lands, and nothing more remained of the monster.

Then Coyote’s oldest friend, Fox, pointed out the beautiful, bountiful land where they were standing, and said: ‘But you have given nothing to this place!’

‘Why did you not tell me earlier?’ snorted Coyote. ‘Bring me some water.’

He washed his hands, and sprinkled the bloody water around where he was standing, sealing the destined arrival of one last people: ‘You may be small, because I neglected you, but you will be powerful. Now, only a short time away, will be the coming of the human race.’

It seems we’ll never know the precise moment when man first reached North America. The most mainstream pre-historical consensus, though, is that the first arrivals poured over the Bering land bridge from northern Asia around 13,000 years ago, chasing the mammoths, mastodons and giant bison to extinction as they went.

The local archaeological evidence, of arrowheads, rock art and cooked animal bones, points to the earliest population of the Columbia Plateau, the inland mountain and forest watershed of the great Pacific-bound river, as dating back at least 11–12,000 years. As tribal memory tells it, one of the earliest names for the first people of the plateau was Cupnitpelu, The Emerging or Walking Out People. One story recalls that the animals met to discuss the impending arrival of man; those that decided to help him, such as the salmon and the buffalo, stayed, but those that chose not to help, such as the woolly mammoth and short-nosed bear, left for good.

Once in situ, the Columbia Plateau’s residents certainly played their part in what was probably the most remarkable cultural explosion in human history, as the North American continent began to throw up a wildly diverse wave of new civilizations, each forged by the demands of their surroundings and rendered unique by this capacious land. From the proto-socialism of the Pueblos to the senatorial politics of the New York Iroquois, from the conspicuous, slave-based wealth of some Pacific coast communities to the eternal fires of the Mississippian temple-mound faith, the range, fluidity and distinctiveness of these cultures would fill several lifetimes’ study. It’s estimated that more than six hundred distinct and autonomous societies were in place in Canada and North America by the fifteenth century, speaking a range of at least 250 mutually unintelligible tongues, subdivided many times by dialect.

In the eastern Columbia plateau, in the land surrounding the Snake River, one language group formed around the Sahaptin dialect — and at the centre of the linguistic region lay a loose community of families and bands, dominating the area where the wide Snake, Salmon and Clearwater rivers converge. They came to call themselves Nimiipuu — meaning We, The People.

The Nimiipuu way of life was never trapped in aspic, but was, rather, in constant development and amendment; nevertheless, a snapshot of that lifestyle in the centuries prior to the first approaches of the white man can illuminate a vital, enviable culture. Seminomadic, the Nimiipuu moved about their varied homeland in a seasonal round trip, each village band — only loosely connected to one another, in a friendship recognized as neither tribal nor national — moving to their favoured camping spot to perform each task in the annual natural cycle. There were as many as seventy of these village groups scattered across the homeland, very rarely reaching three hundred members and often much smaller, each with a recognized home base and other seasonal outposts. A leader controlled each band, but with very conditional authority — individual freedom was highly valued and the right to do your own thing was well protected.

Nimiipuu petroglyphs on the banks of the Snake River, thought to be 9–11,000 years old.

That annual natural cycle, essential for the survival of a hunter-gatherer culture, was revered in ceremony and song, providing the basis for all endeavour. With the first melt of spring it was time to head to the alpine meadows and harvest the freshly exposed edible root plants; as June approached the salmon spawn beckoned, and fishing platforms and trapping weirs, known as wallowas, needed building at the most bountiful rapids along the homeland’s rivers; in the height of summer the camas, a kind of wild garlic, bulged beneath lush, wide-open prairies, and the Nimiipuu gathered on the grasslands for weeks of socializing and harvesting; in fall the deer and elk were at their most active and the hunters would disappear into the high country for days in pursuit, while closer to home the serviceberries and huckleberries needed picking and drying. But the long, fierce winter was perhaps the most remarkable season; having dried and stored food in preparation, the Nimiipuu would gather at the base of the lowest, mildest valleys in extended A-framed matting lodges, known as longhouses (sometimes over thirty metres long) to see the snows out together, the families sleeping along the edge of the lodge, with fires burning in the middle. It was a time to make and repair clothes and tools, teach children crafts, and for the elders to tell the young people stories — stories of an earlier time, when people and animals conversed, when the lessons and rules of inhabiting the earth were learned, and the mischievous, capricious Coyote ruled the roost.

It was most certainly not a life of ease, but the Nimiipuu were blessed with a bountiful and ceaselessly beautiful territory, of clean, well-stocked rivers, forests dense with game and plentiful meadows, and their comparative natural wealth and subsequent inclination towards openness, friendliness and, where possible, peace was well captured by one of their earliest non-Indian friends, the historian L. V. McWhorter, in 1952: ‘They were the wilderness gentry of the Pacific Northwest.’

One of the most oft-repeated assertions when modern Nimiipuu discuss their ancestors is that they had no religion in the compartmentalized, Sunday Service meaning; instead they possessed an all-encompassing way of life, in which devotional acts and the actions required for living were inseparable. Spirituality was recognized in everyday moments, such as greeting dawn in prayer or song; in celebrations of the various significant events in the natural calendar, such as the arrival of the salmon or the ripening of the camas roots; and a child’s developing capacity to participate in the life of the band was also sanctified in a series of rites, such as a girl’s first outing to gather roots or a boy’s first hunting expedition.

The most significant and revealing of these rites was the spirit quest, the search for a wyakin, or protective spirit. After several years of preparatory conversations with the elders, each Nimiipuu child (when aged from around nine to fifteen) would head away from the lodges and into the wilderness, without food or water, to begin a lonely, cold vigil for the arrival of their personal wyakin. Sitting alone on a mountain-top or outcrop sometimes for days on end, they would seek the revelation of a source of spiritual strength, an image, sometimes real, sometimes coming in a dream or hunger-induced hallucination, that filled their consciousness and left them certain that protection was being offered — an eagle soaring above them, a bear crossing the horizon, a passing hummingbird, rain falling in the distance. Blessed with this vision, they stumbled back home, now in personal and private possession of a supernatural guardian, to whom they could appeal in times of tribulation, effort and, for some, war.

The wyakin quest offers us today a powerfully illuminating vision: of a Nimiipuu world view in which everything within their lands possessed a spiritual centre. Protection was not the preserve of angels or divinities, because spirits resided in creatures, rivers, land forms, weather patterns, all of creation. And to be connected to that natural order, partly revealed in a knowledge of the patterns and foibles of the local environment on which survival depended, partly in your respect for your spiritual kinship with all nature, was to be a Nimiipuu. The band leader whose eloquence would earn him unwelcome fame, Young Joseph, expressed this state of permanent communion best:

As the Nez Perce man wandered through the forest the moving trees whispered to him and his heart swelled with the song of the swaying pine. He looked through the green branches and saw white clouds drifting across the blue dome, and he felt the song of the clouds. Each bird twittering in the branches, each water-fowl among the reeds or on the surface of the lake, spoke its intelligible message to his heart; and as he looked into the sky and saw the high-flying birds of passage, he knew their flight was made strong by the uplifted voices of ten thousand birds of the meadow, forest and lake, and his heart, fairly in tune with all this, vibrated with the songs of its fullness.

In a time of great stress, he reduced this sentiment to its essence: ‘The earth and myself are of one mind.’

This affiliation to the earth was redoubled by the prominent position that ancestors held in Nimiipuu culture. Referred to often in ceremony and conversation, commemorated in careful genealogy and in the passing on of names, possessions and skills, the ancestors were a constant presence in the villages, with those who have passed on serving both as an example in life and a familiar face in death. Nez Perce spiritual leader Horace Axtell received this explanation from an elder: ‘He said, “This is what we do. We look at these tracks laid by our ancestors and we follow them to where they are now. These tracks lead us to the Good Land, The Good Place, where all Indians go after they have spent their time on this earth.”’

The spiritual power of songs, prayers, dances — and of everyday actions such as berry picking or salmon fishing — thus sprang from two sources, the affiliation to the spirit forces of creation and also the connection, by repetition of their actions, words, names and tunes, with the past Nimiipuu — as Axtell observes, ‘the reason our spirituality is so strong is because it comes from our old people, our old ancestors’.

This tradition contributed greatly to the Nimiipuu’s most historically significant shared characteristic: their attachment to their homelands, to the sparkling landscapes of the Wallowa, Snake, Clear-water and Salmon valleys. If your route to the Good Place is in your father’s footsteps, where else can you live but in his home? And, if the spirits of your ancestors are constantly among you, how much more sacred are the lands in which they are buried — land not demarked by a cluster of wooden crosses and a picket fence, but by the entire area in which your ancestors are part of the spiritual community, a community of which you are also a member? Persuading non-Indian visitors to comprehend this unbreakable bond with a specific area of land and water has always been difficult. Chief Seattle, from another Pacific Northwest tribe, the Dwamish, said the following to a white interloper in 1855:

You must teach your children that the ground beneath their feet is the ashes of our grandparents. So that they will respect the land, tell your children what we have taught our children, that the earth is our mother. Whatever befalls the earth befalls the children of the earth. If you spit upon the ground you spit upon yourselves. Our dead never forget the beautiful world that gave them being.

The Crow chief Curley was forced to make a similar point when trying to preserve the remnants of his people’s homelands in 1912, telling white people who wanted the land for cultivation and enrichment: ‘You will have to dig down through the surface before you can find nature’s earth, as the upper portion is Crow. The land, as it is, is my blood and my dead.’

The homeland was inseparable from both individual growth and community life. Personal wisdom was acquired not only through the ancestors’ stories and skills, but through direct experience of the landscape, the seasonal whims and the interrelations of the flora and fauna, that both dictated survival and taught the young Nimiipuu their inseparable link to what modern Native American thinker Donald L. Fixico calls ‘the Natural Democracy’ of the home landscape — ‘This democracy is based on respect. In this belief, all things are equally important. Where a native person grows up is relevant to how one understands all things around him or her…and this set of surroundings becomes fixed in the mind like reference points for later in life.’ From a community perspective, the homeland conferred humility: its encapsulation of the past, present and future of the Nimiipuu serving as a reminder from dawn to dusk that individual fulfilment took second place to the continuation of a narrative of which your life was a small but integral part.

It’s important not to romanticize excessively the Nimiipuu’s relationship with the natural world, as many sympathetic chroniclers of Native America have. The image of the American Indian as the irreproachable steward of an unsullied continent is a powerful and popular one — and one that has also been ferociously challenged in recent years. The Nimiipuu, of course, were human beings, inclined towards improving their lives and capable of changing their surroundings, and they affected their landscape through hunting, harvest, burning and grazing. But what seems certain is that not just their spirituality but their survival did depend on a cautious management of the naturally occurring flora and fauna around them. As numerous tribal oral histories testify, if you didn’t let enough salmon escape the fish traps, there’d be nothing in those traps in three years’ time. Hunt elk while they were carrying or caring for foals and there would be fewer elk the following year.

But it also seems clear that in this independent era there was little conflict between the tribe’s stated values and their material ambitions, thanks to a luxury of space — in the years just prior to the arrival of the white man the Nimiipuu are estimated to have numbered from four to six thousand people, enjoying near-exclusive occupation of around thirteen million acres of land. The defining characteristic of the Nimiipuu, in terms of their environmental impact, was simple lack of numbers — they were at a point on the curve where their actions, though crucial to their immediate locality and their own survival, were not likely to shatter entire ecosystems. As a local anthropologist put it to me: ‘It doesn’t really matter if you run a few hundred buffalo off a cliff, if you only do it once a year.’