Полная версия

Rebel Prince: The Power, Passion and Defiance of Prince Charles – the explosive biography, as seen in the Daily Mail

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018

Copyright © Tom Bower 2018

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

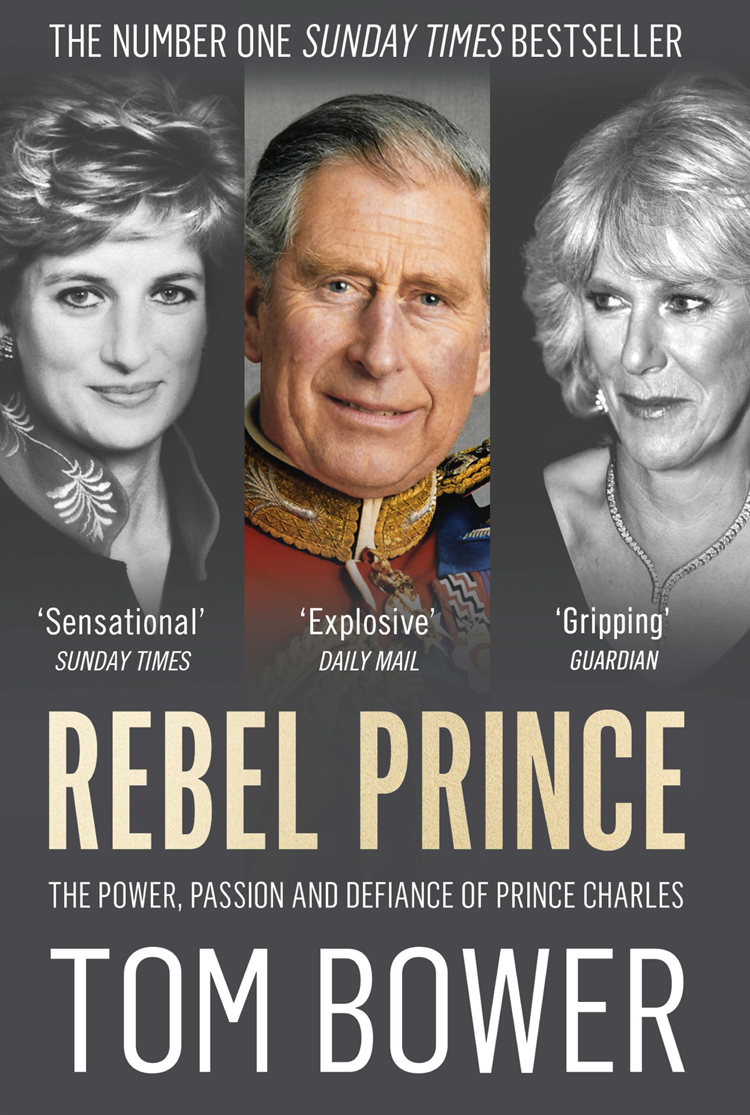

Cover images © Getty Images

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008291730

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780008291778

Version: 2018-09-21

Dedication

To Veronica

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

1 New York, 22 September 1999

2 Plots and Counterplots

3 The Masters of Spin

4 Uneasy Lies the Head

5 Mutiny and Machiavellism

6 Body and Soul

7 The Masterbuilder

8 Teasing the Government

9 Diana’s ‘Rock’

10 A Family at War

11 A Butler’s Warnings

12 A Struggle for Power

13 A New Era Begins

14 Shuttlecocks and Skirmishes

15 The Queen’s Recollection

16 A Private Secretary Goes Public

17 Money Matters

18 Whitewash

19 Revenge and Dirty Linen

20 Drowning Not Waving

21 New Enemies

22 For Better or Worse

23 Resolute Rebel

24 Rules of Conduct

25 King Meddle

26 The Divine Prophet

27 Scrabbling for Cash

28 Marking Time

29 The Prince’s Coup

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Sources

Index

Also by Tom Bower

About the Publisher

Preface

This book is the story of Prince Charles’s battle for rehabilitation after Diana’s death, and his refusal to obey the public’s expectations of a future king. Many books have been written about Charles, but none has fully described the crisis he faced after 1997. For nearly ten years, he was buffeted by scandal. His approval rating fell to the lowest figure for any royal in recent times. His succession to the throne was endangered.

Among the most serious disclosures to undermine public confidence in the prince were those exposed during the unsuccessful prosecution for theft in 2002 of Paul Burrell, Diana’s butler and confidant; the simultaneous revelation of disreputable behaviour within Charles’s household; and the possibility that he had personally interfered in the judicial process. At the end of that two-year drama, Charles’s survival as heir to the throne was on a knife-edge.

Additionally, throughout those years he was repeatedly criticised by the media and politicians for his extravagances. His father denounced him for being a rent-a-royal, yet he continued to sell access to himself – to raise money for his many charities and to indulge in ostentatious luxury. At the same time he provoked a fractious relationship with Tony Blair in his years as prime minister which undermined the prince’s constitutional duty to stay impartial. And he blithely disregarded the disdain of many Commonwealth leaders, which wrecked his assumption that he would automatically inherit leadership of the association of fifty-two countries.

During this period of turmoil, one issue dominated Charles’s life – the status of Camilla Parker Bowles. Ever since they had resumed their relationship in the mid-1980s, he had stubbornly fought to rescue their reputations. Single-mindedly he confronted all the Establishment forces, including the queen, who was determined to prevent their marriage. His principal ally was Mark Bolland, a young media consultant, who for the first time has revealed in this book the intrigues that he masterminded on behalf of Charles and Camilla, which climaxed in their wedding in April 2005. Thereafter, the scandals in Charles’s life diminished, although it would take another six years before the departure of his five most senior advisers signalled the end of the turbulence.

By November 2011, Charles’s reputation as a rebel was truly established. Not only had he defied the nation to marry Camilla, but his championship of controversial causes including the environment, architecture, fox-hunting, complementary medicine and education, had aroused fierce opposition – and also praise. ‘I have never known a man who had better motives for all the trouble he caused,’ comments Thomas Fowler about the eponymous ‘Quiet American’ in Graham Greene’s novel; the same could be said about Charles. Few doubted the sincerity of his campaigns, but many feared that his provocative dissent made him unfit to be king.

He has repeatedly mentioned his devotion to his duty. He believes passionately that he can make Britain a better country and that he can help the disadvantaged. Whatever criticisms may be levelled at him have been mitigated, especially by his admirers, by his commitment to many valuable causes. Many Britons have personal experience of his dedicated visits to schools, hospitals and hospices. Carefully briefed, he talks engagingly to staff, pupils and patients, leaving them all with an enduring memory of his decency.

The contrast for the majority who have not enjoyed a personal encounter is stark. During the many scandals that would have destroyed a lesser man, there has been no evidence that he has suffered a moral struggle. Shame and guilt seem foreign to him. Despite all the eyewitness accounts of his melancholia and self-doubt, Charles has never admitted any wrongdoing. In general terms, he is certainly not misunderstood by the public.

My decision to write about such a familiar character was taken after several months of research. With the exception of Anthony Holden and Jonathan Dimbleby, most of Charles’s subsequent biographers recite events, statements and comments in reverential tones. They do him a disservice. In reality, his life has been a gripping political, financial and personal drama. With hindsight, his survival today may seem preordained, but there were long periods when his future was in doubt, especially after Diana’s death. That his conflicts have been conducted in the spotlight makes his story even more interesting because so much of what occurred has remained in the shadows. I make no claim to have unearthed every truth, but after interviewing over 120 people, many of whom served the royals for long periods and with great distinction and have not given their accounts before, I believe that this book does reveal many new insights about the future king.

As with many of the other personalities I have investigated, I started this biography with limited knowledge about Charles’s life beyond the media reports. Because I have ‘lived’ with him throughout my life – we are of similar ages – I could not fail to be conscious of his exceptional tribulations, but I was unsure how much my research could reveal. The incentive was the suspicion that Charles, like all powerbrokers, must have deployed guile to conceal his tracks.

In the past, my criteria for choosing a personality to investigate have been his or her use – and misuse – of fame and fortune to influence society. Newspaper owners, billionaire tycoons and successful politicians all want to change our lives, and simultaneously to enhance their own reputations. What has fascinated me in all those I have previously covered is their climb from obscurity up the slippery pole, then their battle to stay on top. Along the way they have crushed rivals and subtly altered their own biographies. Often they have publicly paraded their service to mankind, while in reality pursuing largely self-interested agendas.

Charles of course was born at the top of the pole, and though he has not exactly falsified his life’s story, he has concealed many truths. Determined to be a figure of consequence – a long-lasting influence is a sign of greatness – he has used his position since the early 1980s to influence how Britain is governed, and after the mid-1990s employed his powers as a royal to massage the media in order to secure his and Camilla’s survival. My quest was to discover how he manipulated those levers of power.

To my surprise, I found that Charles’s conduct has created a substantial number of victims, many of whom are saddened over how he acted, both in general and towards them. His loyalty, like his attention span, is limited. Embraced today, a favourite can be cast out tomorrow. Like some feudal lord, he presides at the centre of a court with no place for democracy or dissenting views. Unlike the queen, with her genius in being able to unite the nation, especially in difficult times, Charles divides his countrymen. Clearly he enjoys provoking argument, but only on his terms. He has refused to engage in debate. Advisers know that to say ‘No’ will simply prompt his search for a replacement who will say ‘Yes.’ Every decision is his and his alone.

For over thirty years, the Prince of Wales has been prey to his follies. Since 1997 he has resorted to machination and media manipulation to restore his position. Although the large number of British people who previously supported the succession passing directly from the queen to William gradually diminished and then rose again, Charles’s rehabilitation is still unfinished business. His popularity, as I write in early 2018, remains disconcertingly low.

As a committed monarchist, I want Charles to become king, to bequeath the throne in a healthy state to his son, whose popularity will protect the institution during his father’s short reign. Whether and how that happens depends on Charles’s age at the time of his coronation. At the moment, neither Charles nor indeed anyone can predict how the country will react to the queen’s death. Will Britain allow him to inherit the throne smoothly, and watch Camilla anointed as queen? Or will the nation resent Charles and his final ascent? He will undoubtedly become king; but the circumstances are in doubt.

The central question posed at this stage of his life is what kind of monarch will Charles make – given that he is the most unpopular heir for generations. Had the queen died a decade ago, his controversial interventions could well have provoked a constitutional crisis. However, over the past seven years he has moderated his speeches in public, and has tried to encourage the belief that his takeover will be much more acceptable than even the most loyal monarchist could have imagined. His efforts have not been wholly convincing. After speaking to so many of those who have lived with and loved the royals, I share their trepidation over whether Charles can become a unifying monarch. At the end of writing this book, I am convinced that he is determined to make his mark on British history, and will not choose an impartial silence during his inevitably short reign. He remains a historian, writer and political activist, and will want to cement Charles III in people’s memories for centuries to come. How he might achieve that of course remains a puzzle, but to some extent is answered in what follows.

During my research, I inevitably encountered a large number of different opinions. All are reflected in the book. Readers will not be surprised that many of the quotations are anonymous. Those who still associate with Charles and Camilla – as friends or employees – understandably do not want their relationship endangered. To protect them, I have made a point of disguising many of my sources. However, the reader can be assured that every quotation is accurate and was noted during my interviews. Although the two decades covered in my book can be understood only by referring to aspects of what went before, I have restricted such excursions into the past to what is sufficient to understand the present.

Finally, researching this book has been an unexpected pleasure, not only because I have come to understand so many previously unknown conflicts and hitherto imperfectly reported events, but also because Charles emerges as an exceptional character. Easy to like and easy to dislike, he is the unique product of Britain’s genius – a rebel prince, eventually to become a rebel king.

1

New York, 22 September 1999

Her anger was uncontrolled.

‘I won’t stop it. It’s my life and it’s the right thing to do.’

From a suite in New York’s Carlyle Hotel, Camilla Parker Bowles was laying down the law. Her outburst was directed not only at the Prince of Wales but also at his friend Nicholas Soames, the Conservative MP and grandson of Winston Churchill. At the other end of the line, Charles was three thousand miles away, fretting in his study at Highgrove, his Gloucestershire home. He had just passed on the news that Soames had been protesting about her high-profile visit to America.

‘There’s too much publicity,’ Soames had told Charles. ‘It’s that bloody man Bolland.’

‘Well,’ the heir to the throne had replied, ‘let’s all have a meeting with Mark when he returns and he’ll explain everything.’

Thirty-three-year-old Mark Bolland was in theory the prince’s assistant private secretary, his job since 1996, but in reality he was far more than that – the orchestrator of how Charles and Camilla appeared to the world. He stood now in the Carlyle suite witnessing their argument. Also present was Michael Fawcett, Charles’s trusted servant of over twenty years, again far more than a valet. Both men admired Camilla’s scathing dismissal of Charles’s pleas. In Bolland’s opinion, the London media reports about Camilla’s hectic itinerary in Manhattan justified his gamble to defy Buckingham Palace’s demand that she remain unseen and instead propel her into the spotlight.

‘We have to break eggs to push it,’ he had warned Charles before finalising plans for the four-day trip. ‘Things don’t happen by themselves.’ Charles’s doubts had been dismissed by Camilla, who was determined to emerge from the shadow of her predecessor’s glorious conquering of America in 1985. The fifty-two-year-old Camilla was not pulling back. She handed the phone to her media adviser.

Ever since he was hired, a year before Diana died, Bolland had enjoyed a good relationship with Charles. His sole purpose, his employer had stipulated, was to reverse Camilla’s image as his privileged, fox-hunting mistress, make her acceptable to the public and overcome the queen’s hostility to their being together. At the outset, in 1996, there were constant arguments about how Charles’s relationship with Camilla would end. Three years on, she smelt success. ‘Why can’t I meet your mother?’ she had asked. More frequently she would snap, ‘You’re off to the theatre with friends, so why can’t I come?’ Or, ‘You’re off on Saturday to stay with people who are my friends too, so I should be with you.’ To satisfy her, Bolland’s tactics had hit a new level. ‘We were turning up the gas,’ he would say, ‘because the queen was unmovable.’

‘The strategy,’ he explained to Charles, ‘is to scare the horses a bit. To move the dial.’

‘Go ahead,’ Charles agreed.

Back in London, the Sun had responded to Bolland’s overtures with the headline ‘Camilla Will Take New York by Storm Today’, and had listed the celebrities ‘clamouring for invitations to lunch and dinner’. Further to promote her, Bolland had revealed to the paper that the revered TV personality Barbara Walters was invited to one dinner, while Edmond Safra, a billionaire banker, would give a drinks party and the formidable New York socialite Brooke Astor would host a lunch – at which film star Michael Douglas would describe to Camilla the curing of his sex addiction at an Arizona clinic. In Bolland’s currency, Camilla’s appearance on the newspaper’s front page was a triumph.

Soames had protested about such orchestration. ‘Charles,’ he complained, ‘is not a political campaign. He is not a political party.’ Bolland’s tactics also shocked Robin Janvrin, the queen’s private secretary. The Sun’s threat to campaign against the queen, he protested, was typical of the divisiveness masterminded by Bolland.

Over lunch with the publicist, David Airlie, one of the queen’s most respected advisers, had voiced similar unease. Bolland had retorted, ‘Well, give me the alternative of how we will achieve what we want.’

‘Don’t make it too obvious,’ was Airlie’s advice.

‘What’s the alternative?’ Bolland repeated.

Airlie grimaced but made no suggestions. Employment by the palaces, Bolland understood, brought out the worst in even the best of people.

Accompanied by her loyal assistant Amanda McManus, Camilla had flown to New York on Concorde. Their tickets had been bought by Geoffrey Kent, the financier of Charles’s polo team and the founder and owner of Abercrombie & Kent, the millionaires’ travel agent. Bolland was waiting at Kennedy airport, having flown ahead to supervise the final preparations. Among those helping him were Peter Brown, a well-connected British PR consultant, and Scott Bessent, a rich financier who worked with George Soros.

As soon as Camilla touched down, Bessent flew her to his home in East Hampton to give her two days to recover from jet lag (even the three hours it took Concorde to cross the Atlantic could upset her). He would provide a helicopter to fly her from there to Manhattan. Robert Higdon, the chief executive of Charles’s charity foundation in America, was then meant to introduce the team to Camilla’s hosts, but in the aftermath of a tussle among the courtiers he had been abruptly excluded. Languishing in the hotel lobby while Camilla raged at Charles, Higdon nevertheless negotiated for her visit to be hyped in New York’s society columns. ‘Camilla and Charles knew that I was being beat up by the others,’ said Higdon, ‘but the Boss and the Blonde kept me because they knew the money I was bringing in.’ Charles might not have warmed to him, but he could not do without his money-raising talents.

Over the previous four years Higdon had developed huge affection for Camilla, who, he told a journalist, ‘has more self-confidence than anyone I know. Unlike Charles, who is doubtful and whiney, she’s so tough. She never questions anything.’ That judgement was about to change.

The tension led to disagreement between Charles and his four horsemen Bolland, Kent, Brown and Bessent. Their confidence in the value of publicity had been eroded.

‘It wasn’t the right time,’ concluded Higdon. ‘It didn’t feel right for Camilla. It was too soon.’ She was ‘not great’ with Americans. Even worse, she was lazy. ‘For her to get up in the morning and survive until nightfall is a major effort. It was even hard for her to get out of bed. She tries her best to do nothing during the day.’ On the American trip, ‘the biggest problem was persuading her to dress up for a big occasion. The effort was overwhelming. Camilla was pissed off by the whole thing. It was horrible, a disaster.’

While Camilla argued on the phone, Peter Brown was fretting in Brooke Astor’s luxurious Park Avenue apartment. The guest of honour was already thirty minutes late. ‘She’s gossiping with you-know-who,’ Brown confided to one of the guests, unaware of the true circumstances. But when Camilla did finally arrive, no sign of any argument was visible. That skill offset her limitations, and was adored by Charles.

On public occasions she did her best to shine. Three days before flying to New York she had appeared to enjoy a dinner for fifty guests in the Chelsea home of the Greek shipping and steel magnate Theodore Angelopoulos and his wife Gianna, and a few days earlier she had been jolly at Geoffrey Kent’s fifty-sixth birthday party, despite her intense dislike of two of her fellow guests, Hugh and Emilie van Cutsem, both close friends of Charles.

In her unusual world, Camilla was happier when having dinner later that night at Harry’s Bar with Andrew Parker Bowles, her former husband, and his new wife. Andrew was one of the few among her associates who aroused no antagonism among the courtiers. Others, she discovered, were less fortunate in the vicious intrigues around the court.

A new plot, allegedly inspired by Galen Weston, a Canadian billionaire, had sought to oust Geoffrey Kent from Charles’s inner circle. Weston was irritated that Charles played for Kent’s polo team, and that Kent, rather than Weston, was the team captain. Their rivalry had spilled out into a dispute about a joint property development near Palm Beach. Now Weston was seeking to persuade Charles to dump an ally. Venomous spats among courtiers were not unusual for Charles. Despite the generosity shown to him by Kent, a global networker, Charles rarely reciprocated loyalty. ‘We don’t have close friends,’ he had told a member of the polo team. ‘The royal family does not allow anyone to become too familiar and be privy to our secrets.’

During a helicopter trip – a moment chosen so the police escort could not overhear – Bolland had spoken to the prince about his benefactor’s fate. ‘He’s been a good and generous friend,’ agreed Charles. ‘Tell Stephen not to do anything. I’ve changed my mind.’ Stephen Lamport, Charles’s senior private secretary and Bolland’s superior, was accustomed to cutting off those who had displeased his master, and readmitting those who were pardoned.

Charles’s decisions were often influenced by money, and in recent years Camilla had adopted the same criterion. The previous month, she and Charles, her two children and over twenty friends had sailed around the Aegean on the Alexander, the world’s third largest private yacht. They were the guests of Yiannis Latsis, a foul-mouthed Greek shipping billionaire whose fortune, some gossiped, was based on black marketeering, collaboration with the Nazis, and bribing Arabs for a stake in the oil trade. Six weeks later, after her introduction to Edmond and Lily Safra in New York, Camilla discovered that the billionaire banker also owned a luxury yacht, as well as an eighteen-acre estate in the south of France, La Leopolda, valued at over $750 million.

‘Is there any chance,’ Camilla had asked Higdon, who had made the introduction, ‘that I could stay at Lily Safra’s?’ An invitation to visit St James’s Palace was duly issued to Safra, and soon afterwards Michael Fawcett was arranging Camilla’s holiday on the estate.

Her current trip to New York was part of Charles’s campaign to win over the British people; but in 1999 that struggle was far from won.

2

Plots and Counterplots