Полная версия

Ireland: A Social and Cultural History 1922–2001

IRELAND

A Social and Cultural History 1922–2002

Terence Brown

For Sue, again.

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Preface to the Second Edition

Preface

PART I: 1922–32

1 After the Revolution: Conservatism and Continuity

2 An Irish Ireland: Language and Literature

3 Images and Realities

4 The Fate of the Irish Left and of the Protestant Minority

PART II: 1932–58

5 The 1930s: A Self–Sufficient Ireland?

6 “The Emergency”: A Watershed

7 Stagnation and Crisis

PART III: 1959–79

8 Economic Revival

9 Decades of Debate

10 Culture and a Changing Society

PART IV: 1980–2002

11 The Uncertain 1980s

12 Revelations and Recovery

13 Conclusion: Culture and Memory in an International Context

Acknowledgements

Notes and References

Index

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface to the Second Edition

A new edition of a book written over twenty years ago offers various opportunities. One is the chance to correct errors that marred the earlier version. I have accordingly corrected a number of such errors and am grateful to those who brought some of them to my attention (in particular to Eamon Cantwell who directed me to a dissertation which convincingly identified the editor of the Catholic Bulletin in the 1920s).

Another opportunity that I have taken is to recast material so that where it read in 1981 and 1985, when earlier versions of this work appeared, as referring to recent events or to the present, it now refers clearly to the past. This has involved here and there some changes of emphases and, especially in Part III, the incorporation of some additional information. I should say however that this new edition is by no means presented as a re-written version of the book I originally published in 1981. In the preface to that volume I reflected on the difficulties of the task I had set myself then in composing a work of synthesis when so much primary research on twentieth-century Ireland remained to be done. Of course since that date, as I note in this edition, the field of Irish Studies has burgeoned and more works on the social and cultural history of the period have appeared. However, reading through my own work for the purposes of bringing it up to date in the sense that it now covers the period 1922–2002, I was sufficiently happy with the general thesis I had propounded in 1981 to allow it substantially to stand. Therefore what this book does now offer is a volume not in three parts but in four. Part IV deals with the period 1980 to 2002 (incorporating in chapter eleven some material which first saw the light of day in a postscript to the 1985 version of the text), where the first edition had 1979 as its date of termination. This section of the book is now quite lengthy, addressing as it does the quite remarkable events of the 1980s and 1990s when Ireland went from near bankruptcy to economic resurrection, when the “peace process” was inaugurated and the problem of Northern Ireland was confronted by the governments of Britain and Ireland with sustained determination. It was a period too when the Catholic church experienced crises of proportions that would have seemed unimaginable in earlier decades, as Irish society entered on a phase of profound self-questioning in an era of revelations and remembering. I trust this book will allow readers to consider developments of the last two decades of the twentieth century in the context of what had gone before and will take its place as a contribution to the ongoing debate about Ireland’s present and future.

T.B.

Trinity College, Dublin, 1 March 2003

Preface

The main focus of this work is the intellectual and cultural history of Ireland since independence. It will quickly be evident, however, that I am also interested in establishing the main outlines of the social history of independent Ireland since the Treaty of 1921. I trust that my reasons for entertaining these dual ambitions will be clear from my text, but it may be as well to indicate them very briefly here.

It was necessary to establish an outline of modern Irish social history for this study since to fail to do so would be to suggest that high culture – intellectual endeavour and debate, the arts – has a life completely independent of the social reality in which it occurs of a kind which I do not believe it possesses. Ideologies, ideas, symbols, literary and cultural periodicals, even lyric poems are social facts, just as potato crops, tractors, and new industries are, and they can be fully understood only within the material world in which they come to life. So a recurrent preoccupation of this book in its first two parts is the analysis of how, for much of the period, certain ideas, images, and symbols provided Irish people with part of their sense of national identity. For this was a post-colonial society beset by manifold problems, but anxious nevertheless to achieve an independent and distinctive life. Part III of this book looks at how these conceptions and aspirations fared in the new social order that has been in the making in the last twenty years, following the economic revival of the early 1960s. But what also concerns me throughout is how social and cultural change are involved with one another. So the modernization of the last two decades in Ireland is seen to be in part the result of social and cultural factors that had been in the making since about the period of the Second World War, when the framework that had held together since independence began to disintegrate.

It is this concern to measure change and account for it that determines the structure of the book. Part I explores in detail the social and the cultural life of the Irish Free State in its first decade. Despite some signs of change, there was a conservative continuum with pre-revolutionary Ireland, and minorities and critics in the new order had little chance to make their will felt. Part II considers both how and why that continuity was sustained well into the modern period, but detects social and cultural evidences of major change in embryo and analyzes the possible causes of these. Part III presents the social and cultural history of the last two decades in the Republic of Ireland as a period of striking change when set against the picture that Parts I and II have painted of the earlier years of independence.

In Ireland intellectual, cultural, and social history are each infant disciplines. The writer who aspires to provide a study synthesizing the three areas is faced therefore with many insurmountable difficulties, not the least that much basic research has simply not yet been attempted. As a result, this book is very much a provisional and speculative sketch, with few pretensions to completeness in most areas. It is of course the danger of such sketches, particularly of recent and contemporary history, that they become mere caricatures. But without such attempts to chart the field, more fundamental research may not proceed as it must do if more assured works are to result in the future. It is as a preliminary mapping of the territory that I hope this book may prove useful.

I am grateful to the work of those scholars and critics who have, despite the perils, ventured into the turbulent scas of twentieth-century Irish historical research. My considerable indebtedness to them is clearly evident in my notes and references. Some of them are my colleagues in Trinity College, and I am happy to record here my gratitude to them too for their efforts to respond to my often naive inquiries in the last few years. I am also grateful to Miss Geraldine Mangan and Miss Dee Jones, who typed the manuscript at various stages of its production. To my wife, Suzanne, who arranged many things so that this work might be completed, my gratitude is expressed in the dedication.

T.B.

Trinity College, Dublin, 1977–80

PART I

1922–32

CHAPTER 1

After the Revolution:Conservatism and Continuity

Canonical texts of Irish separatist nationalism have often stressed the social and cultural advantages to be derived from Ireland’s independence from the United Kingdom. A free Ireland would embark upon a radically adventurous programme to restore the ancient language, to discover the vitality residual in a nation devastated by a colonial power, and would flower with new social and cultural forms, testaments to the as yet unrecognized genius of the Gael. Patrick Pearse, a martyr to the separatist cause in the Rising of Easter 1916, had prophesied in a vibrant flight of not entirely unrealistic idealism:

A free Ireland would not, and could not, have hunger in her fertile vales and squalor in her cities. Ireland has resources to feed five times her population; a free Ireland would make those resources available. A free Ireland would drain the bogs, would harness the rivers, would plant the wastes, would nationalize the railways and waterways, would improve agriculture, would protect fisheries, would foster industries, would promote commerce, would diminish extravagant expenditure (as on needless judges and policemen), would beautify the cities, would educate the workers (and also the nonworkers, who stand in direr need of it), would, in short, govern herself as no external power – nay, not even a government of angels and archangels could govern her.1

That the revolutionary possibilities of an independent Ireland as envisaged by Pearse were scarcely realized in Southern Ireland in the first decades of the Irish Free State, which came into being following the Treaty of 1921, should not perhaps surprise. The dissipation of revolutionary aspiration in post-revolutionary disillusionment is by now a commonplace of modern political history. That, however, a revolution fought on behalf of exhilarating ideals, ideals which had been crystallized in the heroic crucible of the Easter Rising, should have led to the establishment of an Irish state notable for a stultifying lack of social, cultural, and economic ambition is a matter which requires explanation. For the twenty-six counties of Southern Ireland which made up the Free State showed a prudent acquiescence before the inherited realities of the Irish social order and a conservative determination to shore up aspects of that order by repressive legislation where it seemed necessary.

One explanation presents itself readily. The stagnant economic conditions which the Free State had inherited made nation-building of the kind Pearse had envisaged most difficult to execute. The beautification of the cities and the education of the workers could not proceed without an economic miracle that faith might generate but works in the form of major investment and bold enterprise would have had to sustain. Neither faith nor works could easily flourish in the insecure economic environment of the Irish Free State in the 1920s, in the aftermath of a civil war.

By 1920 the boom years of the First World War, when agricultural prices had been high, had given way to an economic recession made the more severe by the turbulent years of revolution and fratricidal strife which followed, until a measure of stability was restored in 1923, when the Civil War, which had broken out after the departure of the imperial power, drew to its unresolved close. The first years of the Free State, brought into existence by the Constitution of the Irish Free State Act in 1922 and approved in October of that year, were dogged by intense economic difficulty. This fact may in part account for the timorous prudence of the economic policies adopted by the new Irish administration which emerged after the election of August 1923. From the outset the government was confronted by harsh realities of a kind that might have discouraged the most vigorous of nation-builders. A serious strike of port workers lasted for six months in 1923 (cattle exports dropped by 60 percent during the strike); there was poor weather in 1923 and 1924. The summers “were harsh, gloomy and sunless, while the autumn and winter months were characterized by continuously heavy rains which kept the soil sodden throughout and caused extreme discomfort to grazing cattle.”2 Indeed, not until 1925 was there a fine June to cheer the many farmers of agricultural Ireland.

The economy that the Free State government had inherited and for which it assumed responsibility in these inauspicious circumstances had several major inherent defects. It was stable to the point of stagnantion: a developed infrastructure of railways and canals was not matched by an equivalent industrialization; the economy supported too many unproductive people – the old and young and a considerable professional class; there were few native industries of any size and such as there were (brewing, bacon-curing, creameries, biscuit-making, and woollens and worsteds) were productive of primary commodities and unable to provide a base for an industrial revolution. The gravest problem, however, was the country’s proximity to the United Kingdom with its advanced industrial economy, so that, as the historian Oliver MacDonagh has succinctly stated, “the Free State…was not so much…an undeveloped country, as…a pocket of undevelopment in an advanced region, such as the Maritime Provinces constitute in Canada as a whole or as Sicily does in Italy.”3

Throughout the 1920s the government maintained a strict hold on the public purse, balancing the budget with an almost penitential zeal. Despite the protectionism that the Sinn Féin party had espoused in the previous decade as part of its economic plans for an independent Irish Republic, few tariffs were raised to interfere with free trade. The economic nationalism of the prerevolutionary period gave way to a staid conservatism that did little to alter the economic landscape. The government maintained agricultural prices at a low level to the detriment of industrial development. Accordingly, in the 1920s there were only very modest increases in the numbers of men engaged in productive industry, and the national income rose slowly. The need to restrict government spending meant that many social problems remained unsolved. The slum tenements in the city of Dublin are a telling example. Frequently adduced as a scandalous manifestation of British misrule in Ireland (they deeply disturbed that English patriot, the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, when he worked as a professor of classics in Dublin in the 1880s) and also frequently investigated by official bodies, the tenements of Dublin might well have provided the opportunity for a piece of showpiece reconstruction to a newly independent nationalistic government. In fact, the opportunity so afforded was ignored. Conditions remained desperate. The 1926 census showed that in the Free State over 800,000 people were living in overcrowded conditions (overcrowding being more than two persons per room), many of them in north Dublin City. In the state in 1926 there were 22,915 families living in overcrowded conditions in one-room dwellings, 39,615 families living in two rooms, and, telling statistics indeed, 24,849 persons, living in 2,761 families with nine persons in each, resided in two-room dwellings. Infant mortality figures in Dublin, drawn from the census, tell their own sorry tale. In North Dublin City the average death rate per 1,000 children between one and five years was 25.6, while in the more salubrious suburb of Drumcondra the figure was 7.7 per 1,000 children. A contemporary observer remarked that “the story these tables tell is sordid and terrible, and calls for immediate and drastic action.”4 In fact, no real action was taken until 1932, when a bill designed by the Fianna Fáil Minister for Local Government was introduced envisaging a central role for the government in alleviating the situation. Perhaps poor housing was so endemic a problem in Dublin in the 1920s that it was difficult to imagine a solution.

Other kinds of enterprise were within the imaginative scope of the Free State government of the 1920s. These were to have a considerable effect on social life, particularly in rural areas. In the absence of significant private investment in necessary projects, the Cumann na nGaedheal (the ruling party) administration slipped paradoxically into a kind of state intervention that was quite foreign to its ideological cast of mind. Such enterprises as the Agricultural Credit Corporation and the Electricity Supply Board were the first of the many institutions which, established by successive governments and eventually known as the semi-state bodies, ventured where private capital would not. Indeed, the construction between 1925 and 1929 of a large power station on the river Shannon, under the direction and control of the Electricity Supply Board, was one of the very few undertakings in the first decade of independence which might be said to represent a fulfilment of earlier separatist ambition.

It would be wrong, however, to attribute the devastating lack of cultural and social innovation in the first decades of Irish independence simply to the economic conditions of the country. Certainly the fact that at independence there was no self-confident national bourgeoisie with control over substantial wealth, and little chance that such a social class might develop, meant that the kinds of experiment a revolution sometimes generates simply did not take place. But pre-revolutionary experience had shown that artistic, social, and cultural vitality did not necessarily require great economic resources, since in a society almost equally afflicted by economic difficulties cultural life had flowered and social innovation been embarked upon. Indeed it was to those years of cultural and social activity and to the political and military exploits that accompanied them that the new state owed its existence.

An explanation for this social and cultural conservatism of the new state is, I believe, to be sought in the social composition of Irish society. The Ireland of twenty-six countries which comprised the Free State after the settlement of 1921 was an altogether more homogeneous society than any state would have been had it encompassed the whole of the island of Ireland. The six Northern counties which had been separated by the partition of 1920 from the rest of the country contained the island’s only large industrial centre where a large Presbyterian minority expressed its own distinctive unionist sense of an Irish identity. Episcopalian Anglo-Ireland, its social cohesion throughout the island fractured by partition, remained powerful only in the six counties of Northern Ireland. In the twenty-six counties the field lay open therefore for the Catholic nationalist majority to express its social and cultural will unimpeded by significant opposition from powerful minorities (in Chapter four of this section I discuss the fate of those who attempted opposition). When it is further recognized that much of the cultural flowering of earlier years had been the product of an invigorating clash between representatives of Anglo-Ireland (or those who thought of themselves as such) and an emergent nationalist Ireland at a time when it had seemed to sensitive and imaginative individuals that an independent future would require complex accommodations of Irish diversity,5 it can be readily understood why the foundation of the Irish Free State saw a reduction in adventurous social and cultural experiment. The social homogeneity of the twenty-six counties no longer demanded such imaginatively comprehensive visions.

When finally it is understood that this homogeneous Irish society of the twenty-six-county state was predominantly rural in complexion and that Irish rural life was marked by a profound continuity with the social patterns and attitudes of the latter half of the nineteenth century, then it becomes even clearer why independent Ireland was dominated by an overwhelming social and cultural conservatism. As Oliver MacDonagh remarked, peasant proprietorship, outcome of the land agitation of the previous century “more than any other single force…was responsible for the immobility of Ireland – politics apart – in the opening decades of the…century.”6 The revolution that dispatched the colonial power from the South of Ireland in 1922 had left the social order in the territory ceded to the new administration substantially intact. It was a social order largely composed of persons disinclined to contemplate any change other than the political change which independence represented.

The twenty-six counties of independent Ireland were indeed strikingly rural in the 1920s. In 1926, as the census recorded, 61 percent of the population lived outside towns or villages. In 1926 53 percent of the state’s recorded gainfully employed population were engaged in one way or another in agriculture (51,840 as employers, 217,433 on their own account, 263,738 as relatives assisting, 113,284 as employees, with 13,570 agricultural labourers unemployed). Only one-fifth of the farmers were employers of labour. A majority were farmers farming their land (which had mostly passed into their possession as a result of various land acts which had followed the Land War of the 1880s) on their own account or with the help of relatives. Roughly one-quarter of the persons engaged in agriculture depended for their livelihoods on farms of 1–15 acres, a further quarter on farms of 15–30 acres, with the rest occupied on farms of over 30 acres. Some 301,084 people were employed in various ways on farms of less than 30 acres; 121,820 on farms of 30–50 acres; 117,255 on farms of 50–100 acres; 61,155 on farms of 100–200 acres; and only 34,298 on farms of 200 acres and over. As can readily be seen from these figures, small and medium-sized farms were the predominant feature of Irish agriculture.

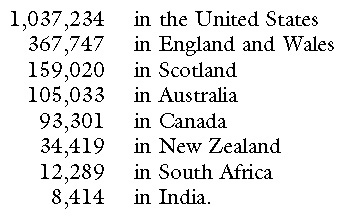

In this rural world, at least since the Famine years of the 1840s, two phenomena had been observable as aspects of the social organization of the countryside – a high average age of marriage accompanied by an extraordinary degree of apparent premarital chastity and the massive haemorrhage of emigration. Some simple statistics highlight these. The 1926 census revealed that in Ireland there was a larger proportion of unmarried persons of all ages than in any other country in which records were kept. In 1926 80 percent of all males between the ages of twenty-five and thirty years were unmarried, with 62 percent of males between thirty and thirty-five years, 50 percent of males between thirty-five and forty, and 26 percent of males between fifty-five and sixty-five also unmarried. The figures for women, while not quite so amazing, were also very high. In the age group 25–30 years 62 percent, 30–35 years 42 percent, 35–40 years 32 percent, and 55–65 years 24 percent were unmarried. These figures reflect a pattern of rural practice (the highest figures relate to rural districts) which had obtained, it seems, since the Famine. It was the 1840s, too, which saw the beginning of the modern Irish diaspora with its perennial emigration, which by the early 1920s meant that 43 percent of Irish-born men and women were living abroad:

This figure of 43 percent compared remarkably with other European countries with traditions of emigration – Norway with 14.8 percent, Scotland with 14.1 percent, and Sweden with 11.2 percent (in 1921) – and most strikingly with most other European countries, where about 4 percent of their populations were overseas. The continuous Irish diaspora, under way since the Famine, kept the population of the country as a whole almost stable throughout most of the modern period.