Полная версия

Liberty’s Exiles: The Loss of America and the Remaking of the British Empire.

Perhaps the most surprising truth about loyalist refugees was how varied a role ideology might play in their decision-making. Though they shared an allegiance to the king and a commitment to empire, their precise beliefs otherwise ranged widely. Some, like Bailey, expressed sophisticated intellectual reasons for their position. For others, loyalism stemmed from a personal commitment to the existing order of things, a sense that it was better to stick with the devil you knew. Also widespread was a pragmatic opinion that the colonies were economically and strategically better off as part of the British Empire.18 The extent and depth of loyalism points to a fundamental feature of this conflict that the term “revolution” belies. This was quite simply a civil war—and routinely described as such by contemporaries on both sides of the Atlantic.19 Polarizing communities, destroying friendships, dividing families—most famously Benjamin Franklin, the founding father, from his only son William, a loyalist—this was the longest war Americans fought before Vietnam, and the bloodiest until the Civil War of 1861–65. Recovering the contingency, coercion, and sheer violence of the American Revolution explains why so many loyalists chose to depart—driven, like Jacob Bailey, by fear of harassment as much as by commitment to principle. By the same token, self-interest could be as powerful a motivator as core beliefs, as the cases of runaway slaves and Britain’s Indian allies perhaps make most clear.

A range of reasons, ideological and otherwise, led all the people in these pages to the same defining choice: to leave revolutionary America.20 This book sets out to explore what happened to them next. Of the sixty thousand loyalists who fled, about eight thousand whites and five thousand free blacks traveled to Britain, often to find themselves strangers in a strange land. The majority of refugees headed straight for Britain’s other colonies, taking up incentives of free land, provisions, and supplies. More than half relocated to the northern British provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Quebec, helping to transform regions once heavily French to the English-dominated Canada of today.* A further six thousand or so migrants, especially from the American south, traveled to Jamaica and the Bahamas—carrying the vast majority of the fifteen thousand exported slaves with them. Some ranged still farther afield. The East India Company army would soon be sprinkled with American-born officers, including two sons of the notorious turncoat Benedict Arnold. An unlucky few ended up among the first convicts sent to Botany Bay, in Australia. And in perhaps the most surprising migration, nearly twelve hundred black loyalists moved to Africa, under the sponsorship of British abolitionists, to found the utopian settlement of Freetown, in Sierra Leone. In short, loyalists landed in every corner of the British Empire. Within a decade of the peace, the map of the loyalist diaspora looked much like the map of the empire as a whole.

A handful of studies have looked at specific figures and sites within this migration. But the loyalists’ worldwide dispersal has never been completely reconstructed.21 A key reason for this lies in the fact that history is so often framed within national boundaries. In the United States, the history of the American Revolution was written by the victors, who were chiefly interested in exploring the revolution’s many innovations and achievements. Loyalist refugees simply fell outside the bounds of American national narratives. They received scant attention from British historians in turn, as embarrassing reminders of defeat—especially given the great triumphs in the Seven Years’ War and the Revolutionary-Napoleonic wars that Britons could focus on instead. Loyalists loom largest, instead, in Canadian history, where they were hailed by some nineteenth-century conservatives as the “founding fathers” of a proudly imperial Anglo-Canadian tradition, and honored as “United Empire Loyalists,” a title conferred by the imperial government on refugees and their descendants. But such treatments reaffirmed the “tory” stereotype and may well have contributed to later scholarly neglect.

There is also a practical reason that nobody has written this global history before. In the 1840s, Lorenzo Sabine, the first American historian who delved into this subject, lamented that “Men who . . . separate themselves from their homes . . . who become outlaws, wanderers, and exiles,—such men leave few memorials behind them. Their papers are scattered and lost, and their very names pass from recollection.”22 In fact, it is remarkable how much does survive: personal letters, diaries, memoirs, petitions, muster rolls, diplomatic dispatches, legislative proceedings. The challenge is putting it all together. Fortunately for twenty-first-century scholars (privileged with funding and access), technology has made it possible to pursue international histories in new ways. One can search library catalogues and databases around the world at the touch of a button, and read digitized rare books and documents on a laptop in one’s living room. One can also travel with increasing ease, to piece together paper trails scattered across continents, and to see what remains of the refugees’ worlds: the houses loyalists built on out-islands of the Bahamas, the precipitous slopes they cultivated above Freetown, or their gravestones, weathered in the Canadian maritime wind.

To look at the American Revolution and the British Empire from these vantage points is to see the international consequences of the revolution in a completely new way. The worldwide resonance of the American Revolution has traditionally been understood in connection with the “spirit of 1776” that inspired other peoples, notably the French, to assert their own rights to equality and liberty.23 Tracing loyalist journeys reveals a different stamp of the revolution on the world: not on burgeoning republics, but on the enduring British Empire. Loyalist refugees personally conveyed American things and ideas into the empire. The fortunate brought treasured material objects: a finely wrought sugar box, a recipe book, or, more weightily, the printing press used by one Charleston family to produce the first newspapers in St. Augustine and the Bahamas.24 But they carried cultural and political influences too—not least the racial attitudes that accompanied the loyalists’ mass transport of slaves. One transformative export was the Baptist faith taken by black loyalist preachers from a single congregation in the Carolina backcountry, who went on to establish the first Baptist churches in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, Jamaica, and Sierra Leone. In the most striking “American” transmission of all, loyalist refugees brought with them a discourse of grievance against imperial authority. In British North America, the Bahamas, and Sierra Leone, loyalist refugees beset hapless British governors with demands for political representation that sounded uncannily like those of their patriot peers. “Loyalist” these days often connotes a die-hard supporter of a cause, but American loyalists were certainly not unblinking followers of British rule.

Considering these kinds of revolutionary legacies brings into focus a remarkable period of transition for the British Empire, and helps make sense of a seeming paradox. The American Revolution marked the empire’s single greatest defeat until the era of World War II. Yet in the space of a mere ten years, it bounced back to an astonishing extent. Building on earlier precedents, British power regrouped, expanded, and reshaped itself across the world—in Ireland and India, Canada and the Caribbean, Africa and Australia.25 All told, the 1780s stand out as the most eventful single decade in British imperial history up to the 1940s. What was more, the events of these years cemented an enduring framework for the principles and practice of British rule. This “spirit of 1783,” so to speak, animated the British Empire well into the twentieth century—and provided a model of liberal constitutional empire that stood out as a vital alternative to the democratic republics taking shape in the United States, France, and Latin America.

What did this postwar restructuring involve, and what role did refugee loyalists play in the process? The “spirit of 1783” had three major elements.26 First and most visibly, the British Empire significantly expanded around the world—and loyalists were both agents and advocates of imperial growth. Historians used to portray the American Revolution as a dividing line between a “first” British Empire, largely commercial, colonial, and Atlantic, and a “second” empire centered in Asia and involving direct rule over millions of manifestly foreign subjects. But loyalist refugees bridged the two. As pioneer settlers in British North America, the Bahamas, and Sierra Leone, they demonstrated the continued vitality of the Atlantic empire alongside what has been described as the empire’s “swing to the east.” They also promoted ambitious expansionist projects elsewhere in the world, championing schemes to extend British sovereignty into Spanish America, or around the western borders of the United States. Far-fetched though some of these ideas can seem in retrospect, they hardly seemed so at a time when the future shape of the United States was very unclear, and Britain (among other European empires) was successfully establishing footholds in some of the most remote quarters of the globe. The first serious proposal to colonize Australia was put forward by none other than an American loyalist.27

Loyalist refugees also illuminate a second feature of the “spirit of 1783”: a clarified commitment to liberty and humanitarian ideals. Although the American Revolution demonstrated that British subjects abroad would not be treated exactly as British subjects were at home, at least when it came to political representation, the revolution also had the effect of deepening an imperial guarantee to include all subjects, no matter what their ethnicity or faith, in a fold of British rights. Loyalist refugees became conspicuous objects of paternalistic attention. Black loyalists got their freedom from authorities increasingly inclined toward abolition, in self-conscious contrast to the slaveowning United States. Needy loyalists of all kinds received land and supplies in an empire-wide program for refugee relief that anticipated the work of modern international aid organizations. Loyalists even received financial compensation for their losses through a commission established by the British government—a landmark of state welfare schemes.

Yet liberal values had their limits, as loyalists discovered at close range. British officials after the revolution by and large concluded that the thirteen colonies had been given too much liberty, not too little, and tightened the reins of administration accordingly. This enhanced taste for centralized, hierarchical government marked the third component of the “spirit of 1783”—and one that loyalist refugees consistently found themselves resisting. Confronted with top-down rule, they repeatedly demanded more representation than imperial authorities proved willing to give them, a discrepancy that had of course undergirded the American Revolution in the first place. And for all that loyalists profited from humanitarian initiatives, they also ran up against numerous seeming contradictions in British policy. This was an empire that gave freedom to black loyalists, but facilitated the export of loyalist-owned slaves. It gave land to Mohawk Indian allies in the north, but largely abandoned the Creeks and other allies in the south. It promised to compensate loyalists for their losses but in practice often fell short; it joined liberal principles with hierarchical rule. Across the diaspora, the refugee loyalist experience would be marked by a mismatch between promises and expectations, between what subjects wanted and what rulers provided. Such discontents proved a lasting feature of the post-revolutionary British Empire—and another line of continuity from the “first” into the “second” empire, from the first major war of colonial independence to later anti-colonial movements.

Few could have predicted just how quickly the “spirit of 1783”—committed to authority, liberty, and global reach—cemented in the aftermath of one revolution would be tested by another. In early 1793, less than a decade after Evacuation Day, Britain plunged into war with revolutionary France in an epic conflict that lasted virtually uninterrupted till 1815. Fortunately for Britain, already tested by republican dissent in America, the “spirit of 1783” provided a ready set of practices and policies to pose against French models. In contrast to French liberty, equality, and fraternity, Britain offered up its own more limited version of liberty under the crown and hierarchical stability. This wasn’t so much a counter-revolutionary vision as it was a post-revolutionary one, forged in part from the lessons of the war in America. In the end, it prevailed. Britain’s comprehensive victory over France in 1815, on the battlefield and at the negotiating table, served to validate the “spirit of 1783” over French republican and Napoleonic alternatives, and to make liberalism and constitutional monarchy a defining mode of government in and beyond Europe.28

To this day, legacies of the British Empire’s liberal constitutionalism endure alongside American democratic republicanism—making the “spirit of 1783” arguably just as important an influence in twenty-first-century political culture as the spirit of 1776. And yet, from some angles, maybe the spirit of 1776 and the spirit of 1783 didn’t look so different. The post-revolutionary United States tussled with ambitions and problems remarkably like those faced by the British Empire from which it broke away: a drive for geographic expansion, competition with European empires, management of indigenous peoples, contests over the limits of democracy and the morality of slavery.29 While the United States drafted its constitution, British imperial authorities developed constitutions for their colonial domains, from Quebec to Bengal.30 While the British Empire made up for the loss in America by expanding into new colonies, the United States quickly embarked on empire-building itself, pushing west in a thrust that more than doubled the nation’s size in just a generation. Though their political systems revolved around a fundamental divergence—one a monarchy, the other a republic—the United Kingdom and the United States shared ideas about the central importance of “liberty” and the rule of law.31

In 1815, Britain and its allies won at Waterloo; the British Empire was on top of the world. Loyalist refugees by then had carved out new homes and societies in their sites of exodus. After all the deprivation, the upheaval, the disappointment, and the stress, many surviving refugees, and even more of their children, eventually discovered a kind of contentment. Their trajectories from loss to assimilation mirrored the ascent of the British Empire as a whole, from defeat to global success. Loyalists who had left the United States for the British Empire were subjects of the world power that enjoyed international preeminence for the next century or more. They were, in this sense, victors after all.

THIS BOOK RECOVERS the stories of ordinary people whose lives were overturned by extraordinary events. To chronicle their journeys is also to chart them. The first three chapters describe the American Revolution as loyalists experienced it; the factors that caused them to leave; and the process by which most of them departed, in mass evacuations from British-held cities—an important yet little-known piece of revolutionary history. Chapters 4–6 follow the refugees to Britain and British North America (the eastern provinces of present-day Canada), to look at three features of loyalist settlement: how the refugees were fed, clothed, and compensated; how they formed new communities; and how they influenced the restructuring of imperial government after the war. Chapters 7–9 turn farther south, to explore the fortunes of refugees in the Bahamas, Jamaica, and Sierra Leone. Loyalists in these settings struggled against adverse environmental and economic conditions at the best of times, and the onset of the French Revolutionary wars only made things worse, by heightening conflicts over political rights and tensions around issues of slavery and race. The final chapter moves through the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812 to consider where loyalists stood a generation after their migrations began, from the place where they started—the United States—to the place that had overtaken America in imperial significance, India.

Since no one volume can contain sixty thousand stories, I have chosen to focus on a cluster of figures who capture different varieties of the refugee experience. Together they provide an intimate sense of what this exodus actually meant and felt like to its participants. The refugees belonged at once to a very big world—an expanding global empire—and to a surprisingly small one, in which scattered individuals retained personal connections over enormous distances of space and time. Remarkably many of these figures also moved more than once. Moving was part of the job for the imperial officials who recur in these pages, notably Sir Guy Carleton, commander in chief in New York and governor in Canada; and Lord Dunmore, governor of pre-revolutionary Virginia and the post-revolutionary Bahamas. For displaced civilians, however, repeated migrations underscored the dislocating effects of war, as well as the capacity of empires to channel human populations along certain routes.32

Elizabeth Lichtenstein Johnston, a middle-class loyalist from Georgia, was acutely aware of living in a world in motion. In her late teens when the war ended, Johnston led her growing family through the emptying British outposts of the south: Savannah, Charleston, and St. Augustine in turn. These journeys prefigured a longer postwar odyssey, when the Johnstons established homes in Scotland, Jamaica, and at last Nova Scotia, fully twenty years after their peregrinations began. The family of New York landed magnate Beverley Robinson provides an instructive parallel to the Johnstons, from a position of greater privilege. War reduced Robinson from sprawling acres in America to a modest dwelling in Gloucestershire. But he invested his remaining resources in placing his children in the military, one of the best mechanisms for upward mobility the British Empire had to offer. Robinsons went on to thrive in imperial service everywhere from New Brunswick to Jamaica, Gibraltar, Egypt, and India. Some of Robinson’s grandchildren even found fortune where their forebears had lost it, back in New York. Between them, the Johnston and Robinson families bring to life preoccupations shared by the majority of white loyalist refugees: to maintain social rank and respectability; to rebuild family fortunes; and to position their children for success. Their papers also give poignant insight into the emotional consequences of war on refugees coping with loss, dislocation, and separation.

Many refugees saw their journeys as devastating personal setbacks. But some realized that these turbulent times might offer great opportunities as well. Perhaps the most visionary of these dreamers was North Carolina merchant John Cruden, who watched both his fortune and British supremacy collapse around him, yet tirelessly promoted schemes to restore both. Cruden’s projects to rebuild a British-American empire showed just how dynamic British ambitions remained after the war. In similar vein, Maryland loyalist William Augustus Bowles “went native” among the Creek Indians, and used his position between cultures to promote the creation of a loyal Indian state on the southwestern U.S. border. A more substantial effort to assert Indian sovereignty was led by Mohawk sachem Joseph Brant, the most prominent North American Indian to portray himself as a loyalist. From his postwar refuge near Lake Ontario, Brant aimed to build a western Indian confederacy that could protect native autonomy in the face of relentless white settler advance.

For black loyalists, of course, the losses inflicted by revolution were offset by an important gain: their freedom. This was the first step toward futures few could have imagined. David George, born into slavery in Virginia, found both freedom and faith as a Baptist convert in revolutionary South Carolina. After the war he emigrated to Nova Scotia, where he began to preach, quickly forming whole Baptist congregations around him. When he decided a few years later to seek a new Jerusalem in Sierra Leone, many of his followers made the journey with him. Networks of faith connected black loyalists around the Atlantic. George’s spiritual mentor George Liele traced another line from the backcountry into the British Empire when he evacuated with the British to Jamaica, where he founded the island’s first Baptist church.

To reconstruct these individual journeys, I have visited archives in every major loyalist destination to find refugees’ own accounts of what happened to them. The interpretations people give of their behavior are usually refined in retrospect, and many of the writings loyalists produced about themselves had some agenda. This was manifestly the case for the single biggest trove of documents, the records of the Loyalist Claims Commission, set up to compensate loyalists for their losses. Every claimant had a vested interest in proving the strength of his or her loyalty, the intensity of suffering, and the magnitude of material loss. The best sources relating to black loyalists display another bias, having been shaped by British missionaries keen to advance an evangelical purpose. The most accessible sources concerning Indian nations were produced for and by white officials, placing an imperial filter over their contents. And then there were the usual distortions wrought by memory. Personal narratives written many decades after the war, like Elizabeth Johnston’s, often emphasized tragedies, injustices, and resentments that lingered in the mind long after more benign recollections had faded. Early-nineteenth-century accounts produced in British North America, especially, could be skewed as heavily toward portraying loyalists as victims as competing accounts in the United States were toward presenting them as villains.

No sources of this kind are ever purely objective. But the way people tell their stories—what they emphasize, what they leave out—can tell the historian as much about their times as the concrete details they provide. The refugees’ tragic discourse deserves to be listened to not least because it is so rarely heard. It captures aspects of human experience that are often left out of traditional political, economic, or diplomatic histories of this era, yet that are vital for understanding how revolutions affect their participants, how empires interact with their subjects, and how refugees cope with displacement. It inverts more familiar accounts to give a contrasting picture of alternatives, contingencies, and surprises. Nobody could predict at the outset how the American Revolution would turn out, whether the United States would survive, or what would become of the British Empire. For American colonists standing on the threshold of civil war in 1775, there would be a tumultuous, harrowing, and unpredictable journey ahead.

* From the American Revolution up to Canadian Confederation in 1867, these provinces were collectively known as British North America. “Canada” was synonymous with the province of Quebec until 1791, when it was divided into the provinces of Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) and Lower Canada (present-day Quebec).

PART I

Refugees

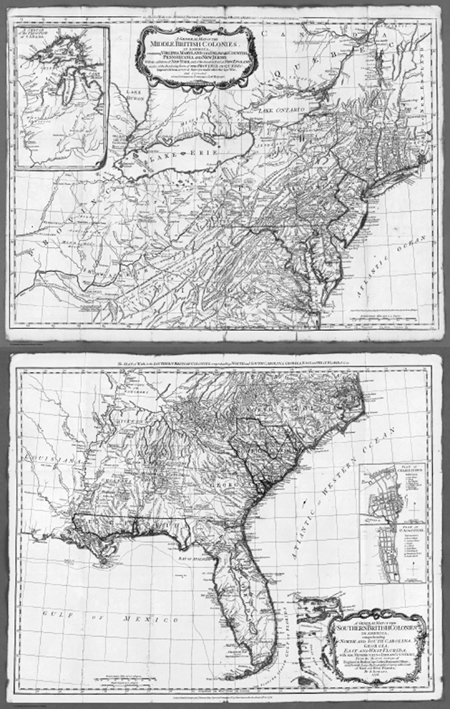

After Thomas Pownall, A General Map of the Middle British Colonies in America, 1776. Opposite bottom: Bernard Romans, A General Map of the Southern British Colonies in America, 1776.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.