Полная версия

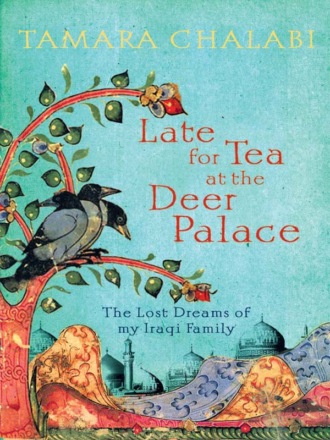

Late for Tea at the Deer Palace: The Lost Dreams of My Iraqi Family

In the wake of what I saw for myself in their homeland, my family and their stories made me wonder anew about my own origins. Writing about their experiences challenged my notions of language, as I tried to render an Iraqi Arabic with all its idiosyncratic nuances into English. Most of all, it made me wonder about the very concept of Iraq: as a modern state, an ancient land, a nation, a word, a song, a river, a grave, a shrine, a statue of a deer.

In writing this book, I have been fortunate to have had access to a wealth of material: oral histories, archive materials, newspapers, buildings, relics, memoirs, music, interviews and photographs. This book is my attempt to make the unruly disciplined, to assemble the disordered, unorganized parts of the past into a cohesive narrative. As Iraq has an ancient oral tradition, and a great deal of this story was transmitted to me orally, I have tried to respect those elements, and to remain faithful to and respectful of the memories my family have entrusted to me. The timescale of memory is not the same as the timescale of history. Major periods of history can be summarized while minor periods can be expanded. This was certainly true of my family, who when speaking to me dwelled on their happy childhoods in Iraq, but for whom the revolution and many of the years following it passed in a blur. My family’s stories of Iraq are more personal and intimate than a dispassionate and neatly constructed history. They show the country through the lives of people who have loved it.

BOOK ONE

Fallen

Pomegranates

DECEMBER 2007

I am walking through Kazimiya’s alleyways, exploring the crumbling houses with Fatima, a friend from the town, and looking for the old family home. We are following the directions of an elderly historian who is too frail to show us the way in person. He has directed us verbally: turn left by the old train station, right at the donkey stables and left again by the old water pump. Because Kazimiya is a shrine town, and therefore quite conservative, I am wearing an abaya – a long over-garment – which keeps slipping off my head.

Narrow channels of water flow through the middle of the cobbled streets we walk along. Children play and old men sit in their shop fronts, watching us and muttering to each other as they wonder what these strangers are looking for. I wince, thinking about the century that has passed since my grandmother walked these same streets as a little girl, a daughter of this town, and of the many waves of people who have passed through this frontier land, contested between the Ottomans and Persia over many centuries, and later between the British and now the Americans. My grandmother was born an Ottoman subject, just like a native of Istanbul or Izmir, and here I am trying to find remnants of that time and place. She certainly wouldn’t have struggled with the abaya as I do now, nor needed directions to find the main square.

We head towards the side gate of the shrine, Bab al-Murad, said to have been designed by the angel Gabriel, where my grandmother and many others once gave offerings to the poor in gratitude for prayers answered by the seventh Imam. I stop and do the same as I wait to go inside to make my wish.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.