Полная версия

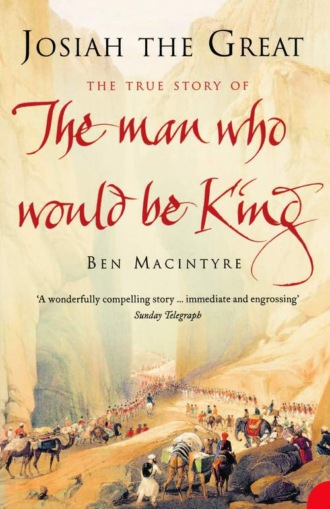

Josiah the Great: The True Story of The Man Who Would Be King

Harlan grew up in the America of Thomas Jefferson, a place of infinite space and possibility. Explorers like Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had started to open up the western two thirds of North America, but vast areas of the globe remained undiscovered and unmapped: the interior of Africa, Australia, Antarctica and, somewhere beyond the borders of India, the mysteries of Central Asia and China. The very breadth of the American continent inspired faith in the potential of a world to be discovered. Walt Whitman rejoiced in the scale of the American horizon:

My ties and ballasts leave me, my elbows rest in sea-gaps,

I skirt sierras, my palms cover continents,

I am afoot with my vision.

Intrepid Americans were moving west in their thousands; young Harlan, however, shed the ballast of his childhood and headed east.

Josiah’s wanderlust, and his growing interest in medicine, can be traced to the influence of his brother Richard. Three years older than Josiah, Richard had entered the medical department of the University of Pennsylvania, and then travelled to Calcutta as a surgeon on an East India Company ship in 1816. After a year at sea he had returned to complete his medical degree, bringing back tales of his voyage and the sights and sounds of India. In the spring of 1820 Joshua Harlan arranged a job for Josiah as ‘supercargo’, the officer in charge of sales, on a merchant ship bound for Calcutta and Canton.

Before setting sail for the East, Josiah joined the secret fraternal order of Freemasons. Quite when or why he came to take the oath is unclear, but there was much in Freemasonry to attract a man of Harlan’s temperament: the emphasis on history (Freemasonry traces its origins to the stonemasons who built Solomon’s Temple), on masculine self-sufficiency and the exploration of ethical and philosophical issues. America’s Masonic lodges tended to draw freethinkers and rationalists, men of politics and action: a third of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence, including George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, had been Masons. Joined by high ideals and a shared fealty to the lodge, Freemasons were expected to demonstrate the utmost tolerance while following a moral system clothed in ritual with allegorical symbols adopted from Christianity, the Crusaders of the Middle Ages and Islam. Like Rudyard Kipling, who would also join the organisation as a young man, Harlan ‘appreciated Freemasonry for its sense of brotherhood and its egalitarian attitude to diverse faiths and classes’.

Harlan seldom discussed his religious beliefs, but his Quaker upbringing moulded him for life. Founded in England in the seventeenth century, the Quaker movement had taken deep root in America, with a credo that set its adherents apart from other Christians. Quakers – a name originally intended as an insult because they ‘tremble at the word of God’ – worship without paid priests or dogma, believing that God, or the Inner Light, is in everyone. All of human life is sacred. ‘Therefore we cannot learn war anymore,’ declares the Quaker testimony. ‘The Spirit of Christ which leads us into all truth will never move us to fight and war against any man with outward weapons, neither for the Kingdom of Christ nor for the kingdoms of this world.’ Harlan was brought up in a spirit of religious egalitarianism: men and women were granted equal authority in meetings, Quakers declined to doff their hats to those of higher status, and as early as 1774 the Society of Friends prohibited Quakers from owning slaves. Quaker mysticism was directed towards social and political improvement rather than dry theological speculation. In the course of his life Harlan would move away from some Quaker tenets, most notably the prohibition on war, but the religion remained central to his character and beliefs, revealing itself in a hardy independence of thought, belief in sexual equality, deep-rooted opposition to slavery and a marked disinclination to bow and scrape to those who considered themselves his superiors.

Harlan’s journey to the East would last thirteen months, taking him to China, India and then, with a full cargo of Eastern merchandise, back to Philadelphia. Enchanted by his first adventure on the high seas, he was preparing to set sail again in the summer of 1821 when he accidentally fell in love.

Harlan never mentioned the name of his first love, whose memory he carried with him for the rest of his life. He refers to her obliquely in his writings, but he was too much of a gentleman ever to divulge her identity. Yet he bequeathed a clue. Among the handful of documents he left behind, sandwiched between a miniature watercolour and a recipe for Albany cakes, is a floral love poem in his own handwriting, entitled ‘Acrostick in explanation of the lines addressed to Miss Eliza S. on presenting a bouquet’.

Each quickening pulse in Coreopsis speaks

Lo at first sight my love for thee was mov’d

Iris love’s messenger salutes those cheeks –

Zephyrs! sweetly breathe where Alfers lov’d

Althea says with passion I’m consumed

Be wreathed the moss rose bud and locust leaves

Emblem of love confess’d beyond the tomb –

Thy Captive made, Peach blossoms fernèd leaves

Heliotropes blue violet and Tulip red

Secure devotion love its declaration –

Whilst ecstasy from fragrant Jess’mine’s bred –

Ambrosia means love’s acceptation

In Verbena, Daisy red, Cowslip and Mignonette

Must sense and beauty, grace, divinity set.

From Marigold – that’s cruelty! – abstain

And Rose, fair lady, for it means disdain!

This style of love poetry is now, mercifully, long out of fashion, but Harlan’s horticultural verse was the product of some expert pruning: reading the first letter of the first fourteen lines reveals the name ELIZABETH SWAIM.

The Swaims were a large, well-to-do Philadelphia clan of Dutch origin. Early in 1822 Josiah Harlan and Elizabeth Swaim were engaged, although no formal announcement was made. Harlan again set sail for Canton, telling his fiancée that they would be married when he returned home the following spring.

Eliza Swaim seems to have had second thoughts from the moment the ship left port, but for months, as Harlan slowly sailed east, he remained unaware that she had jilted him. Not until Richard’s letter caught up with him in Calcutta did he discover that Eliza had not only broken off their engagement, but was now married. A decade later, Harlan was still angrily denouncing the woman who had ‘played him false’. When Joseph Wolff, an itinerant missionary, met him for the first time in 1832, Harlan unburdened himself: ‘He fell in love with a young lady who promised to marry him,’ Wolff noted in his journal. ‘He sailed again to Calcutta; but hearing that his betrothed lady had married someone else, he determined never again to return to America.’ He would stick to his vow for nearly two decades. But he would keep the love poem to ‘Eliza S.’ until he died, alongside a second floral poem, written after he had received the devastating news, as bitter as the first was adoring.

How sweet that rose, in form how fair

And how its fragrance scents the air

With dew o’erspread as early morn

I grasped it, but I grasped a thorn.

How strange thought I so fair a flower,

Fit ornament for Lady’s bower,

Emblem of love in beauty’s form,

Should in its breast conceal a thorn.

Harlan embraced his own loneliness. Henceforth, the word ‘solitude’ appears often in his writings. He had reached out and grasped a thorn; he would never clasp love in the same way again. The broken engagement was a moment of defining pain for Josiah, but Elizabeth Swaim had also set him free. Cutting himself off from home and family, determined never to return, he now plunged off in search of a different sort of romance, seeking adventure, excitement and fortune, caring nothing for his own safety or comfort.

Emotionally cast adrift in Calcutta, Harlan learned that the British were preparing to go to war against Burma and needed medical officers for the campaign. The jungles of Burma seemed an adequate distance from Pennsylvania, and so, following his brother’s example, Harlan signed up as a surgeon with the East India Company. That he did so in order to escape the mortifying memory of Eliza Swaim is apparent from a reference in his unpublished manuscript. ‘Gazing through a long window of twenty years’, he wondered what would have happened ‘if, in place of entering the service for the Burma War in the year 1824, I had then relinquished the truant disposition of erratic motives and taken a congenial position in the midst of my native community and quietly fallen into the systematic routine of ordinary life – if I had sailed for Philadelphia instead of Rangoon or had I listened to the dictates of prudence, which accorded with the calculations of modest and unambitious views, and not a personal incident that occurred during my absence from home’. This ‘personal incident’ would lead Harlan into a life worthy of fiction – which in time it would become. From now on he began to fashion his self-plotted saga, acutely aware of his role as the protagonist, narrator and author of his own story. ‘It is from amongst such incidents and in such a life that novelists have sought for subject matter,’ he wrote. ‘In those regions, which are to me the land of realities, have the lovers of romance delighted to wander and repose and dream of fictions less strange than realizations of the undaunted and energetic enterprise of reckless youth.’

Calcutta, where Harlan now abandoned ship, was the seat of British rule in India, the capital city of the Honourable East India Company. The ‘Grandest Society of Merchants in the Universe’, ‘the Company’, as it was universally known, was an extraordinary outgrowth of British history, an alliance of government and private commerce on an imperial scale, and the precursor of the British Raj. Chartered under Elizabeth I, by the early nineteenth century the Company could wage war, mint currency, raise armies, build roads, make or break princes and exercised virtual sovereignty over India. Twenty years before Harlan’s arrival, the Company’s Governor General had become a government appointment, serving the shareholders while simultaneously acting in Britain’s national interests. The Company was thus part commercial and part political, ruling an immense area through alliances with semi-independent local monarchs, and controlling half the world’s trade. This was ‘the strangest of all governments, designed for the strangest of all empires’, in Lord Macaulay’s words. Only in 1858, in the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny, would the British crown take formal control of the subcontinent.

Service with the East India Company promised adventure and advancement, and potential wealth. More immediately, for Harlan, it offered distance from Eliza Swaim, and a paid job as a military surgeon. That he had never actually studied medicine was not, at least in his own mind, an impediment. Years later he would claim that he ‘had in his early life studied surgery’, but what medical knowledge he possessed appears to have been entirely self-taught. A medical textbook was a part of every educated traveller’s baggage, and before his first voyage to Canton, Harlan had ‘taken a few of his brother’s medical books with him and then decided to use their contents in treating persons other than himself’. The rough life aboard a merchant vessel had presented opportunities to observe and treat a variety of ailments and injuries. In July 1824, with no qualifications whatever, relying on an alloy of brass neck and steely self-confidence, Harlan ‘presented himself for examination at the medical board, and was appointed surgeon at the Calcutta general hospital’. Calcutta was one of the most unhealthy places on earth, and with war looming in Burma, surgeons, however novice, were in hot demand.

For decades the expansionist Burmese had been steadily advancing along the eastern frontier of the Company’s dominion, conquering first Assam and then Shahpuri Island near Chittagong, a Company possession. Fearing an attack on Bengal itself, the British now responded in force with a seaborne army of some 11,000 men. On 11 May 1824, using a steamship in war for the first time, British forces invaded and captured Rangoon, but with Burmese resistance hardening, Calcutta ordered up fresh troops. Harlan had been on the payroll for just a few months when, to his intense satisfaction, he was transferred to the Artillery of Dum-Dum and ordered to the battlefield; if he had any qualms about violating the Quaker rules on pacifism, they were suppressed. The voyage to Rangoon by boat took more than a fortnight. Harlan was deeply impressed by the resilience of the native troops. ‘The Hindu valet de chambre who accompanied me consumed nothing but parched grain, a leguminous seed resembling the pea, during the fifteen days he was on board the vessel.’ Arriving in Rangoon in January 1825, Harlan was appointed ‘officiating assistant surgeon and attached to Colonel George Pollock’s Bengal Artillery’.

The British defeated a 60,000-strong force outside Rangoon, forcing the enemy into the jungle, but they were suffering numerous casualties, mostly through disease, and the Burmese showed no sign of surrendering. In February a young English adventurer named James Brooke was ambushed by guerrillas at Rangpur, and severely wounded by a sword thrust through both his lungs. Brooke would recover and go on to become Rajah Brooke, founder of the dynasty of ‘white rajahs’ that ruled Sarawak in Borneo from 1842 until 1946, the best-known example of self-made imperial royalty. It is tempting to imagine that the future Prince of Ghor tended the wounds of the future Rajah of Sarawak, but sadly there is no evidence of a meeting between Harlan and Brooke, two men who would be kings.

That spring the artillery pushed north, and Harlan was present at the capture of Prome, the capital of lower Burma, after ferocious hand-to-hand fighting. The Treaty of Yandaboo, in February 1826, brought the First Anglo-Burmese War to a close. After battling through two rainy seasons, the Company had successfully defended and extended its frontier, but at the cost of 15,000 troops killed and thousands more injured or debilitated by tropical disease. One of the casualties was Harlan himself, who was put on the invalid list and shipped back to Calcutta suffering from an unspecified illness.

Once he had recuperated, he was posted to the British garrison at Karnal, north of Delhi, and it was there that he discovered a soulmate who would become his ‘most faithful and disinterested friend’. Looking back, Harlan would write that this companion ‘rendered invaluable services with the spontaneous freedom of unsophisticated friendship, enhancing his favours by unconsciousness of their importance. He accompanied me with, unabated zeal throughout the dangers and trials of those eventful years.’ His name was Dash, a mixture of red setter and Scottish terrier, a dog whose fierce and independent temperament matched Harlan’s exactly. ‘Dash never maintained friendly relations with his own kind. Neither could he be brought to tolerate as a companion any dog that was not perfectly submissive and yielding to the dogged obstinacy and supremacy of an imperious and ambitious temper,’ wrote Harlan. The description fitted both man and dog. ‘Dash had always been carefully indulged in every caprice and accustomed to the services of a valet. He was never beaten and his spirit, naturally ardent and generous, maintained the determined bearing which characterises a noble nature untrammelled by the servility arising from harsh discipline. Dash could comprehend the will of his master when conveyed by a word or a glance.’

Harlan passed the time in Karnal training his puppy, cataloguing the local flora, treating the dysentery of the soldiers, and reading whatever he could lay his hands on. In 1815, literary London had been briefly enthralled by the publication of An Account of the Kingdom of Caubul, and its Dependencies in Persia, Tartary, and India, comprising a View of the Afghaun Nation and history of the Dooraunee Monarchy, a colourful two-volume description of the exotic, unknown land inhabited by the Afghan tribes. The author was the splendidly-named Mountstuart Elphinstone, an East India Company official who in 1808 had led the first ever diplomatic mission to Afghanistan, accompanied by an entire regiment of cavalry, two hundred infantry, six hundred camels and a dozen elephants. The Englishman described a wondrous journey among ferocious tribesmen and wild animals, through a landscape of savage beauty. Elphinstone had been received at Peshawar, with great pomp and ceremony, by Shah Shujah al-Moolk, the Afghan monarch then in the sixth precarious year of his reign. Ushered into the royal presence, the Englishman had found the king seated on a huge golden throne. ‘We thought at first he had on an armour of jewels, but, on close inspection, we found this to be a mistake, and his real dress to consist of a green tunic, with large flowers in gold, and precious stones, over which were a breastplate of diamonds, shaped like two flattened fleur-de-lis, an ornament of the same kind on each thigh, large emerald bracelets and many other jewels in different places.’ On Shujah’s arm shone an immense diamond, the fabled Koh-i-Noor, or Mountain of Light.

Elphinstone’s orders were to secure Afghan support against a potential Franco-Persian alliance, and his visit became an elaborate exchange of diplomatic pleasantries and gifts. The English officers were presented with dresses of honour, the Oriental mode of conferring esteem. In return Elphinstone showered the Afghan court with presents, to the ire of the Company’s bean-counters who rebuked him for ‘a principle of diffusion unnecessarily profuse’. In spite of the rather unseemly way Shujah gloated over his haul (he particularly coveted Elphinstone’s own silk stockings), the Englishman had described the king and his sumptuous court in the most admiring terms: ‘How much he had of the manners of a gentleman, [and] how well he preserved his dignity.’ The British mission never penetrated past the Khyber Pass and into the Afghan heartland, for as Shujah explained, his realm was deeply unsettled, with the looming possibility of full-scale rebellion. Indeed, within a few months of Elphinstone’s departure Shujah would be deposed.

Although Elphinstone had never actually seen Kabul, his Account was heady stuff. Harlan absorbed every thrilling word of it: the jewels, the wild Afghan tribesmen, the sumptuous Oriental display and the ‘princely address’ of the handsome king with his crown, ‘about nine inches high, not ornamented with jewels as European crowns are, but to appearance entirely formed of those precious materials’. The book’s vivid depiction of the Afghan character might have described Harlan himself: ‘Their vices are revenge, envy, avarice and obstinacy; on the other hand they are fond of liberty, faithful to their friends, kind to their dependents, hospitable, brave, hardy, laborious and prudent.’

Reading by candlelight in Karnal cantonment, Harlan dreamed of new adventures. He was growing impatient with the routine of service in the East India Company, and increasingly unwilling to follow the orders of pimply young Englishmen. One of the many contradictions in his personality was his insistence on strict military discipline among his subordinates, while being congenitally incapable of taking orders from those ranking above him. The freeborn American was also decidedly free with his opinions, and the young surgeon’s outspokenness, often verging on insubordination, did not endear him to his superiors: ‘Harlan does not appear to have obtained a very good name during his connection with the Company’s army, which he soon quitted,’ wrote a contemporary. One later account claimed that he was on leave when the order was issued for the dismissal of all temporary surgeons, but Harlan insisted that the decision to leave the service was his alone.

Elphinstone painted a thrilling picture of princely Afghan warlords battling for supremacy, in a medieval world where a warrior could win a kingdom by force of arms. ‘A sharp sword and a bold heart supplant the laws of hereditary descent,’ wrote Harlan. ‘Audacious ambition gains by the sabre’s sweep and soul-propelling spur, a kingdom and [a] name amongst the crowned sub deities of the diademed earth.’ The Company, by contrast, kept subordinate princes on the tightest rein, and in British-controlled India the native monarchs were little more than impotent figureheads, he reflected. ‘Under English domination we have his stiff encumbered gait, in place of the reckless impetuosity of the predatory hero. The cane of the martinet displaces the warrior’s spear.’

Harlan was already imagining how his own bold heart and sharp sword might be used to supplant the laws of hereditary descent, and in the summer of 1826 he ended his allegiance to the British Empire. He had witnessed British imperialism in action, but his own imperial impulse was of a peculiarly American sort. Thomas Jefferson himself had spoken of ‘an empire for liberty’ and imagined the ideals of the American Revolution stretching from ocean to ocean and beyond; the America of Harlan’s youth had expanded at an astonishing rate. He had been just four years old when Jefferson doubled the nation’s size by purchasing from France the Louisiana Territory west of the Mississippi, and throughout his childhood the white population had been steadily pushing westward. Harlan’s world view reflected this urgent, embracing outward impetus, what one historian has called ‘the heady optimism of that season of US empire at surge tide’. New lands and peoples were there to be discovered, scientifically explored, introduced to the benefits of civilisation by force, exploited and brought into the great American experiment. That the inhabitants did not actually wish to be absorbed into a greater America was immaterial.

Harlan deeply admired Jefferson, and retained a lifelong faith in republican values, but at the same time he considered himself a ‘high Tory in principles’ and an admirer of ‘kingly dignity’. America had won its independence from Great Britain just sixteen years before Harlan’s birth. He came to loathe the more oppressive aspects of British imperialism, yet he firmly believed that sovereign power should be invested in a single, benign ruler, whether that power came through democracy (as with Washington and Jefferson) or through conquest. In this sense, Harlan’s imperialism resembled the original imperium, the authority exercised by the rulers of Rome over the city state and its dominions. In his mind, no figure in history represented this combination of civilised expansionism and kingly dignity more spectacularly than Alexander the Great. ‘His power was extended by the sword and maintained by the arts of civilization. A blessing to succeeding generations by the introduction of the refinements of life, the arts and sciences, in the midst of communities exhausted by luxury or still rude in the practices of barbarism … Vast designs for the benefit of mankind were conceived in the divine mind of their immortal founder, the universal philanthropist no less than universal conqueror.’ Conquest, benevolence, philanthropy and immortality: Harlan saw Alexander’s empire, like the expanding American imperium, as a moral force bringing enlightenment to the savages, and he would come to regard his own foray into the wilderness in the same way: not simply as a bid for power, but the gift of a new world order to a benighted corner of the earth.