Полная версия

Into the Raging Sea: Thirty-three mariners, one megastorm and the sinking of El Faro

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2018

Copyright © 2018 by Rachel Slade

Cover design by Allison Saltzman

Cover images © Mike Hill/Photographer’s Choice/Getty Images

Rachel Slade asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008302436

Ebook Edition © August 2017 ISBN: 9780008302450

Version: 2018-04-23

Dedication

To the families and friends of those lost on El Faro.

No one should have to endure such sorrow.

Epigraph

There is nothing more enticing, disenchanting, and enslaving than the life at sea.

—LORD JIM, JOSEPH CONRAD

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

CAST OF CHARACTERS

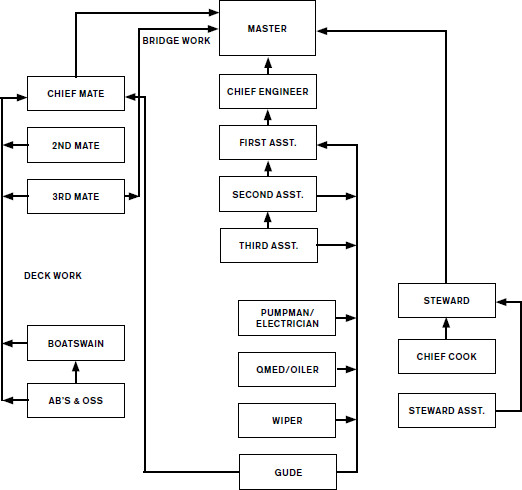

CHAIN OF COMMAND ABOARD EL FARO

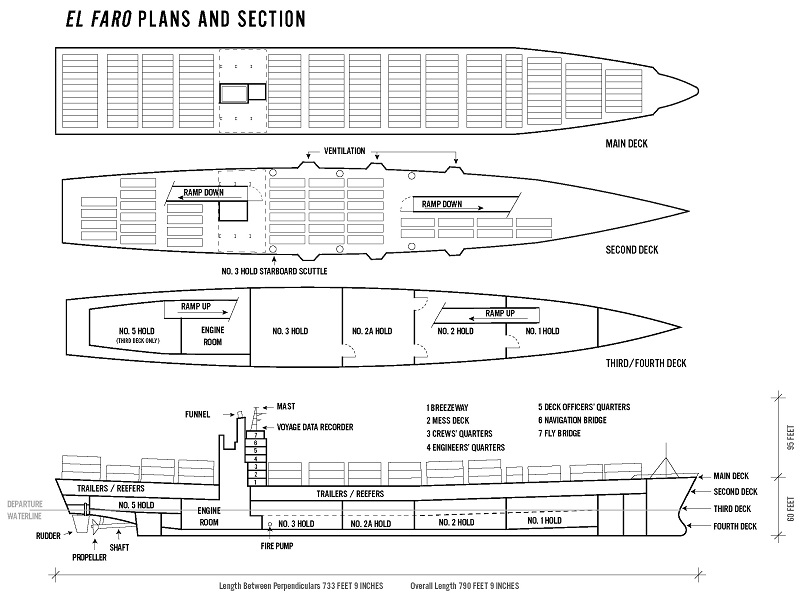

EL FARO PLANS AND CROSS-SECTION

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

PART I

CHAPTER 1: THE CLOCK IS TICKING

CHAPTER 2: BLOUNT ISLAND

CHAPTER 3: TROPICAL STORM JOAQUIN

CHAPTER 4: THIRD MATE JEREMIE RIEHM

CHAPTER 5: A HURRICANE IS NOT A POINT ON A MAP

CHAPTER 6: SECOND MATE DANIELLE RANDOLPH

CHAPTER 7: COLLISION COURSE

CHAPTER 8: HULL NUMBER 670

CHAPTER 9: AFTERNOON

CHAPTER 10: CAPTAIN MICHAEL DAVIDSON

CHAPTER 11: QUESTION AUTHORITY?

CHAPTER 12: THE JONES ACT

CHAPTER 13: EVENING

CHAPTER 14: NIGHT

CHAPTER 15: NECESITAMOS LA MERCANCÍA

CHAPTER 16: DAWN

CHAPTER 17: THE RAGING SEA

CHAPTER 18: WE’RE GONNA MAKE IT

PART II

CHAPTER 19: WE’VE LOST COMMUNICATION

CHAPTER 20: SEARCH AND RESCUE

CHAPTER 21: FLIGHT TO JACKSONVILLE

CHAPTER 22: SHIPS DON’T JUST DISAPPEAR

CHAPTER 23: PROFIT AND LOSS

CHAPTER 24: THE TRUTH IS OUT THERE

CHAPTER 25: HOW TO SINK A SHIP

CHAPTER 26: ADMIRAL GREENE CLEARS THE AIR

CHAPTER 27: PORTRAIT OF INCOMPETENCE

CHAPTER 28: MISSION NUMBER TWO

CHAPTER 29: THE PROOF IS IN THE PUDDING

CHAPTER 30: VOICES

CHAPTER 31: TWENTY-FOUR MINUTES

CHAPTER 32: SPIRITS

EPILOGUE

CREW LIST

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A NOTE ON SOURCES

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

CAST OF CHARACTERS

FEATURED EL FARO OFFICERS AND CREW

DECK DEPARTMENT

Michael Davidson, 53, Master

Steven Shultz, 54, Chief Mate, First Watch

Danielle Randolph, 34, Second Mate, Second Watch

Jeremie Riehm, 46, Third Mate, Third Watch

Frank Hamm, 49, Able Seaman, Helmsman for the First Watch

Jackie Jones, 38, Able Seaman, Helmsman for the Second Watch

Jack Jackson, 60, Able Seaman, Helmsman for the Third Watch

ENGINEERING

Richard Pusatere, 34, Chief Engineer, Dayworker

Michael Holland, 25, Third Assistant Engineer

LaShawn Rivera, 32, Chief Cook

James Porter, 40, Utility Person

Jeff Mathias, 42, off-duty Chief Engineer in charge of Polish workers aboard El Faro

EL FARO FAMILY AND FRIENDS

Laurie Bobillot, mother of Danielle Randolph

Jill Jackson-d’Entremont, sister of Jack Jackson

Robert Green, stepfather of LaShawn Rivera

Rochelle Hamm, wife of Frank Hamm

Glen Jackson, brother of Jack Jackson

Jenn Mathias, wife of Jeff Mathias

Marlena Porter, wife of James Porter

Frank Pusatere, father of Richard Pusatere

Deb Roberts, mother of Michael Holland

Korinn Scattoloni, friend of Danielle Randolph

OFF-DUTY EL FARO OFFICERS

Charlie Baird, off-duty Second Mate

Jim Robinson, off-duty Chief Engineer

OTHER TOTE SHIP’S OFFICERS

Ray Thompson, Isla Bella Master, former Chief Mate of El Faro

Earl Loftfield, El Yunque Master after the loss of El Faro

Kevin Stith, El Yunque Master during accident voyage

JACKSONVILLE PILOT

Eric Bryson, River Pilot with St. Johns Bar Pilot Association

RETIRED MARINERS

Eric Axelsson, retired TOTE Master, Davidson’s relief on El Faro until August 2015

Paul Haley, retired TOTE Chief Mate

Jack Hearn, retired TOTE Master

John Loftus, retired Horizon Shipping Master

Pete Villacampa, retired TOTE Master

Bill Weisenborn, retired TOTE Port Captain

SUN SHIPBUILDING AND DRY DOCK

John Glanfield, retired Shipbuilder

Eugene Schorsch, retired Naval Architect

NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE

James Franklin, Director of the National Hurricane Center, Miami

US COAST GUARD DC HEADQUARTERS

Rear Admiral Paul Thomas, Assistant Commandant for Prevention Policy

Captain Jason Neubauer, Head of USCG El Faro investigation

Commander Michael Odom, USCG Traveling Ship Inspector, former Rescue Swimmer

Commander Charlotte Pittman, Deputy Chief, USCG Office of Public Affairs, former helicopter pilot

Keith Fawcett, Marine Board Investigator

US COAST GUARD SEARCH AND RESCUE

Captain Rich Lorenzen, Commanding Officer, Air Station Clearwater

Commander Scott Phy, Operations Officer, Air Station Clearwater

Lieutenant Dave McCarthy, MH-60T Pilot, Aircraft Commander for Minouche rescue

Aviation Survival Technician 1st Class Ben Cournia, Rescue Swimmer during Minouche rescue

Lieutenant John “Rick” Post, MH-60T Pilot, Co-Pilot for Minouche rescue

Aviation Maintenance Technician 2nd Class Joshua Andrews, Flight Mechanic during Minouche rescue

Lieutenant Commander Jeff Hustace, HC-130 pilot, Aircraft commander for El Faro search

Captain Todd Coggeshall, Chief of Incident Management, 7th Coast Guard District, Miami

Operations Specialist 2nd Class Matthew Chancery, Search and Rescue Mission Coordinator, 7th Coast Guard District Command Center, Miami

NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD

Tom Roth-Roffy, NTSB Chief Investigator

Eric Stolzenberg, NTSB Nautical Architecture Group

Doug Mansell, NTSB Technology Specialist

Mike Kucharski, NTSB Investigator

TOTE EXECUTIVES

Peter Keller, EVP, TOTE

Phil Greene, President, TOTE Services

Phil Morrell, VP Marine Operations, TOTE Maritime

Tim Nolan, President, TOTE Maritime Puerto Rico

John Lawrence, Designated Person Ashore and Manager of Safety and Operations

Jim Fisker-Andersen, Port Engineer

CHAIN OF COMMAND ABOARD EL FARO

EL FARO PLANS AND SECTION

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

Six microphones installed in the ceiling of El Faro’s navigation bridge recorded twenty-six hours of conversation leading up to the sinking. This audio was captured on a microchip by an onboard Voyage Data Recorder—the ship’s black box. All the dialogue in this book aboard El Faro during her final voyage was taken from a transcription of this audio.

CHAPTER 1

THE CLOCK IS TICKING

The satellite call came into the emergency center at 7:08 on the morning of October 1, 2015.

OPERATOR: Okay, sir.

CALLER: Are you connecting me through to a QI [Qualified Individual]?

OPERATOR: That’s what I’m getting ready now. We’re seeing who is on call and I’m going to get you right to them. Give me one second, sir. I’m going to put you on a quick hold. So one moment, please. Okay, sir. I just need your name please.

CALLER: Yes, ma’am. My name is Michael Davidson. Michael C. Davidson.

OPERATOR: Your rank?

CALLER: Ship’s master.

OPERATOR: Okay. Thank you. Ship’s name?

CALLER: El Faro.

OPERATOR: Spell that E-L …

CALLER: Oh man, the clock is ticking. Can I please speak to a QI? El Faro: Echo, Lima, Space, Foxtrot, Alpha, Romeo, Oscar. El Faro.

OPERATOR: Okay, and in case I lose you, what is your phone number please?

CALLER: Phone number 870-773-206528.

OPERATOR: Got it. Again, I’m going to get you reached right now. One moment please.

CALLER: [Aside.] And Mate, what else to do you see down there? What else do you see?

OPERATOR: I’m going to connect you now okay.

OPERATOR 2: Hi, good morning. My name is Sherida. Just give me one moment. I’m going to try to connect you now. Okay, Mr. Davidson?

CALLER: Okay.

OPERATOR 2: Okay, one moment please. Thank you for waiting.

CALLER: Oh God.

OPERATOR 2: Just briefly what is your problem you’re having?

CALLER: I have a marine emergency and I would like to speak to a QI. We had a hull breach, a scuttle blew open during a storm. We have water down in three-hold with a heavy list. We’ve lost the main propulsion unit, the engineers cannot get it going. Can I speak to a QI please?

OPERATOR 2: Yes, thank you so much, one moment.

Thirty-three minutes later, the American government’s network of hydrophones in the Atlantic Ocean picked up an enormous thud just beyond Crooked Island in the Bahamas. It was a sound rarely heard out there in the deepest part of the sea where, for decades, the government had been recording an endless underwater symphony. Three miles down, they listened to the lonely cries of humpback whales, the eerie hum of earthquakes, and the whirr of submarine propellers. Just white noise, really. But that morning, something huge and audible hit the ocean floor with terrific force.

Based on the positions of the hydrophones, the people listening knew approximately where the object landed. They also knew the precise moment that it hit. But what was it?

That the Americans had been listening in on the ocean since the 1960s was no secret, at least not to mariners. Some older guys remembered laying down the cable decades ago to feed this equipment, which served as the country’s first line of defense against submarine invasion or other nefarious activity on the high seas.

The precise locations within this network were considered classified, but one monitoring station, known as the Atlantic Undersea Test and Evaluation Center (AUTEC), occupies a piece of Andros Island in the Bahamas, just west of Nassau. The thud was notable enough that there was talk among a few members of the armed forces stationed there. That intel simmered among a handful of officers assigned to monitor maritime activity in the Caribbean.

When word got out that a large American container ship had vanished in Hurricane Joaquin somewhere east of the Bahamas, those stationed on Andros Island knew exactly what they’d heard. It was the sound of El Faro colliding with the ocean floor.

CHAPTER 2

BLOUNT ISLAND

JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA, 30.39°N -81.54°W

From above, Jacksonville looks like a battleground between land and water where water is winning. Rivers, streams, and inlets branch like veins folding in on themselves, following their own secret logic; roads curve here and there, searching for a path from one scrap of land to the next. A series of bridges stitches northern Florida’s tenuous coast together.

It was late in the afternoon on September 29, 2015, and Jacksonville’s wide open-for-business highways were choked with commuter traffic baking in the heat of another late September day. Down at the sprawling marine terminal on Blount Island, stevedores loaded El Faro, a 790-foot-long ship, with 25 million pounds of cargo: 391 containers, 238 refrigerated containers, 118 trailers, 149 cars, and enough fructose syrup to make more than one million two-liter bottles of soda.

In his comfortable home at Atlantic Beach, Eric Bryson waited for a call from his dispatcher. Eric was a river pilot with the St. Johns Bar Pilot Association. He made his living divining the secrets of Jacksonville’s waterways to safely deliver tankers, cargo ships, and car carriers up the St. Johns River to the Port of Jacksonville or back out to sea. Federal maritime law requires that every deep-draft vessel hire a local guide like Eric to navigate ships through these waterways so that they don’t collide with each other or the struts of bridges, or take one of the many tight turns too wide and ground on the shallow banks.

To earn his piloting job, Eric had to memorize the twists, hazards, and depths of the St. Johns River in exquisite detail—enough that he could draw a navigable map of it from memory. Though the pilot’s test was only open to seasoned ship captains like him, just the top scorer was considered for the position. When he took the exam in 1991, Eric blew away the other twenty-six applicants.

Since it requires such highly specialized knowledge, piloting is one of the most stable positions in the maritime industry. Getting the St. Johns job meant that Eric could give up the seaman’s life and settle down for the long haul with his wife, Mary. They could work together raising their two kids in the warmth of the Florida sun, and he’d never be more than seven miles out to sea. It was a radically different life from the typical mariner who spends at least ten weeks straight on a ship, often out of communication, far from home.

Eric thinks of his job as a craft. “Any idiot can color inside the lines,” he says of finessing a ship safely in and out of port. “The art of it is coloring outside the lines safely.” Sturdily built, just shy of six feet, bald and bearded, with a face like a benevolent bulldog, Eric is the embodiment of male competence. Ponderous by nature, he does not take anything lightly. Some mariners who’ve worked with him call Eric “the Priest.” All this, combined with his detached Yankee demeanor, puts ship captains at ease when Eric assumes command of their vessel.

The pilot dispatcher’s call for SS El Faro came at six o’clock. The container ship was just about ready to leave port, but she was running an hour late. She’d been delayed because she’d been incorrectly loaded—someone had accidentally transposed a few numbers in the ship’s loading software, causing the weight of the cargo to be unevenly distributed, which resulted in a noticeable list. The stevedores had had to scramble to shift cargo around to get her upright once again.

Eric knew El Faro and her two sister ships well—they’d been running twice weekly from Jacksonville to San Juan for nearly two decades, and he’d piloted them up and down St. Johns River dozens of times over the years. He knew many of the deck crew and officers, too, if not by name, at least by face. They were nearly all Americans. These days, that was notable. Most of the ships coming in and out of Jacksonville were registered in foreign countries and crewed by a mix of international laborers—predominantly Philippine.

By the time Eric got the call that hot Wednesday evening, his small travel bag was packed. He’d been following El Faro’s loading progress all day. He grabbed his navy-and-yellow pilot’s jacket and walked through the kitchen door to one of his company’s white Subarus, perpetually parked in the driveway.

As he drove to the terminal, a concrete expanse about the size of Central Park surrounded by a high chain-link fence, Eric cleared his head of the little things that might distract him. He needed intense focus to do his job right. Eric was acutely aware that in the world of big ships, complacency meant death. Now nearing sixty years old, he wanted to get out before his job killed him. Which it nearly did, twice.

To bring ships into Jacksonville, Eric had to board them at sea. He rode in his pilot boat seven miles out to the vessel, at first invisible on the horizon, just a blip on the radar, then looming large as he and his driver pull alongside. Riding up next to the massive, impermeable steel hulls never ceased to give Eric a thrill. If the winds and seas were high, the ship could trace out a big, lazy circle in the water to create a temporary lee for the small pilot boat.

Big ships rarely stop or drop anchor for pilots—they have so much momentum that they’d take miles to come to a halt, and even then, they’d drift with the winds and currents; instead, the pilot boat nestles up alongside like a pilot fish clinging to a whale shark, then tries to keep up with the ship, about 11 miles per hour. The two vessels aren’t ever tethered together.

The small boat is outfitted with an external set of stairs leading to a platform, like a kitchen ladder that someone screwed onto its deck. Moored at the pilot association’s office, the stepladder steps off into the void. But alongside a thousand-foot-long ship, it’s the only way a pilot has any chance of climbing aboard.

Once the boat is riding alongside the ship, a small door in the enormous hull opens, a friendly face pops out from the steel wall, and a hand drops down a rope ladder as the pilot boat’s driver tries to maintain the same speed and course as the ship. The pilot climbs his stepladder and then pauses, clinging to his platform, gauging the situation. The bottom rung of the huge ship’s rope ladder dangles a few feet away from the pilot’s shoes, but the two vessels are bobbing up and down at different rates. The pilot times his leap as the ship and pilot boat perform their version of synchronized swimming. He grabs hold of the rope ladder and scrambles up.

I once took a piloting trip with Eric. I thought I was mentally prepared for that moment when you had to take that leap of faith. But when confronted with all this—the flimsy rope ladder, the wall of black steel, the deep water rushing below with nothing to catch me if I missed—I panicked. Freud says that those who are afraid of heights don’t trust their bodies not to jump. If my hands decided to let go, I would plummet between the two vessels and drown.

“Grab on! Climb up,” Eric commanded. I reached out and gripped that rope ladder like my life depended on it, which it did. And then I scurried ten feet up the hull, ten steps straight up, holding my breath until I was safe on the deck, looking back down at Eric’s head as he followed me scaling the side of the ship.

Pilots have missed that ladder. They’ve slipped and fallen into the sea where they were crushed between their boat and the ship. In October 2016, a pilot with more than a decade’s worth of experience died this way on the river Thames.

Eric was once reaching for the ladder when his driver pulled away too soon, leaving him straddled between the two vessels. Eric was forced to make a split-second decision: jump for the ladder and risk missing it, or fall back into the pilot boat. He hurled himself toward the deck of his boat and saved his life but shattered his heel. He was out of work for months, and in immeasurable pain, but hated being on meds. His second accident was caused by his bag—caught on the pilot boat platform, it yanked him back, and when he fell onto the deck, he broke his back. He’s never fully recovered from that. But he’s alive.

Pilots board a berthed container ship like anyone else—up the gangway or loading ramp.

That’s how Eric got onto El Faro on the evening of September 29.

He parked his car at Blount Island Marine Terminal at 7:30 and walked across the expanse of tarmac by the fading light to the ramp. As he approached El Faro, Eric regarded her dark blue steel hull. Like all massive ships, El Faro was a paean to modern engineering—a floating island capable of moving the weight of the Eiffel Tower through the ocean at 25 miles per hour. She was as long as the Golden Gate Bridge is high; it would take more than four minutes for a person to walk from bow to stern. Designed in the late 1960s, she was built for speed at a time when fuel was cheap and fast shipping fetched premium pricing. To reduce drag, she had a narrow beam that tapered steeply and evenly to her sharp keel.