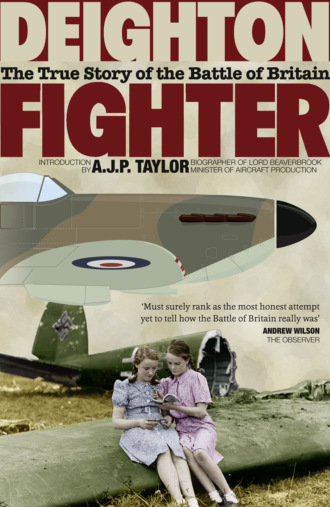

Fighter: The True Story of the Battle of Britain

Полная версия

Fighter: The True Story of the Battle of Britain

Жанр: детективытриллерыкниги о войнеисторическая литературасовременная зарубежная литературасерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу