Полная версия

Game of Spies: The Secret Agent, the Traitor and the Nazi, Bordeaux 1942-1944

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins 2016

Text © Paddy and Jane Ashdown Partnership 2016

Extract from ‘As I Walked Out One Evening’ © the Estate of W. H. Auden,

reproduced by permission of Curtis Brown Ltd

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the author and publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any future editions.

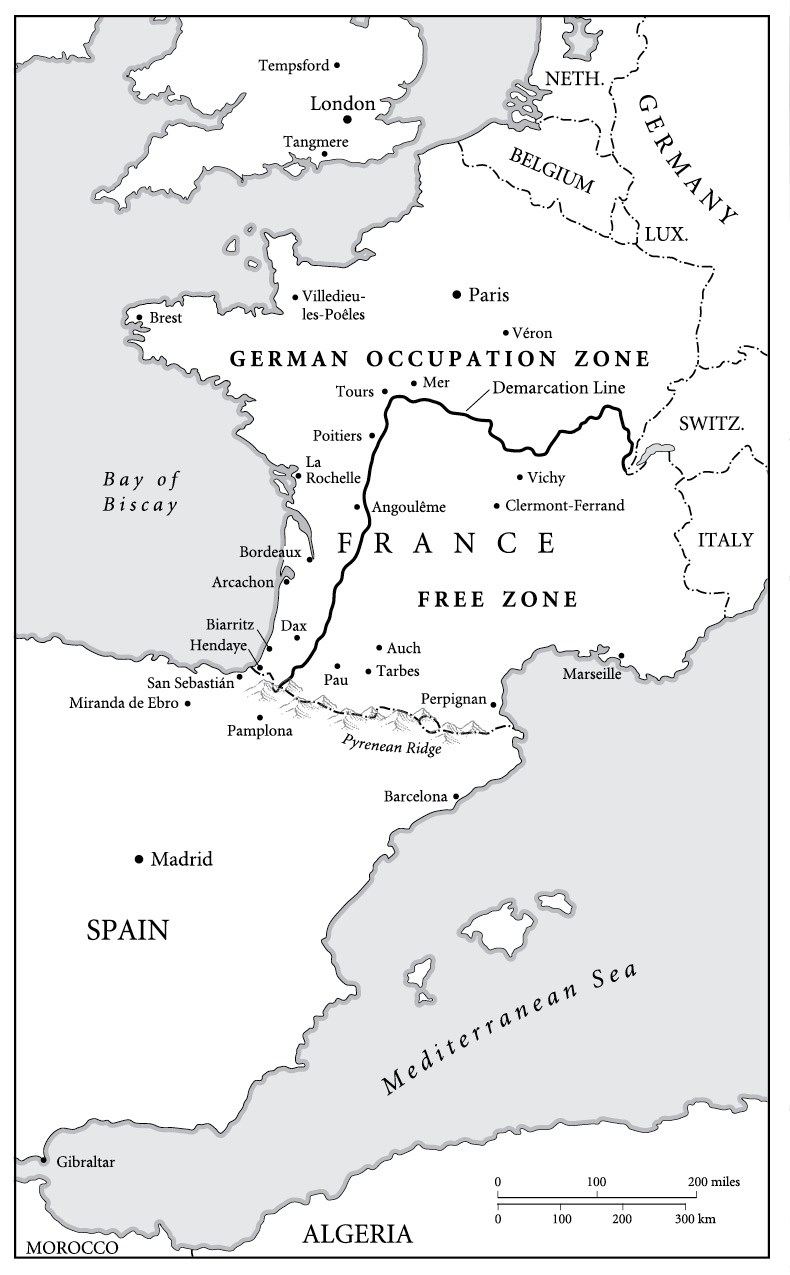

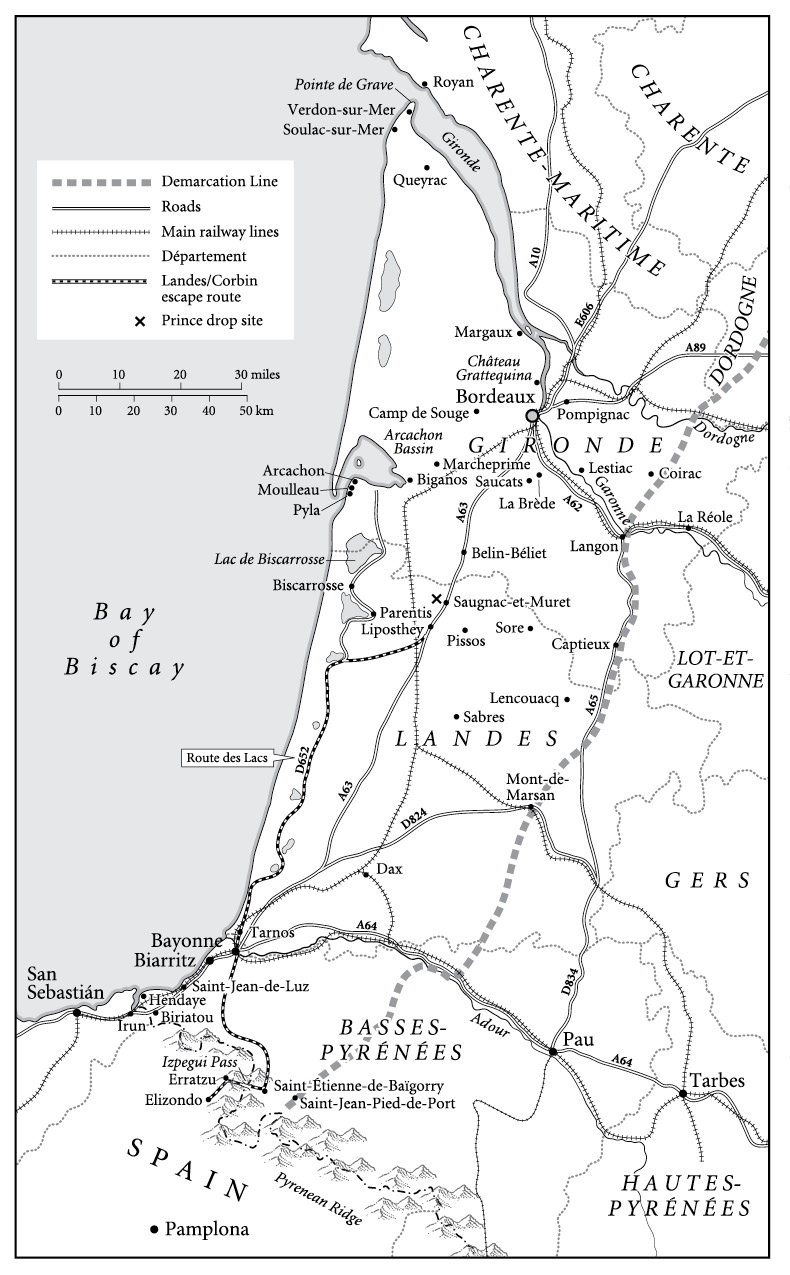

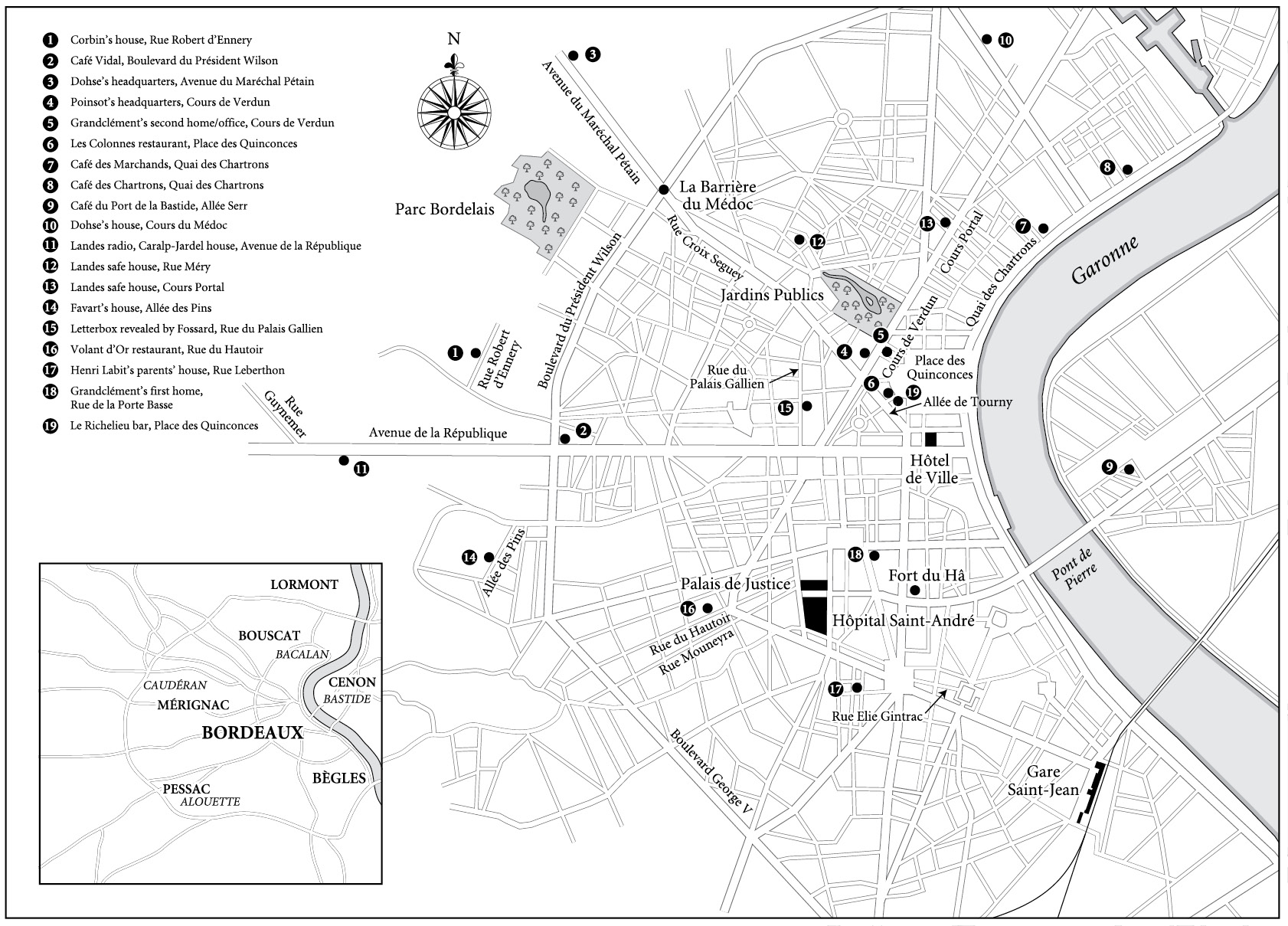

Maps by John Gilkes

Cover photograph © CollaborationJS / Trevillion Imanages

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008140847

Ebook Edition © September 2016 ISBN: 9780008140830

Version: 2017-04-11

DEDICATION

To the young men and women whose lives were changed in Room 055 of the Old War Office Building in London – and ended in the death camps of Nazi Europe.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

Author’s Note

Maps

Prologue: The Execution

1 Bordeaux – Beginnings

2 Roger Landes

3 Friedrich Dohse

4 André Grandclément

5 A Happy Man and a Dead Body

6 Scientist Gets Established

7 A Visitor for David

8 Crackers and Bangs

9 Businesses, Brothels and Plans

10 ‘Je suis fort – Je suis même très fort’

11 A Birthday Present for Friedrich

12 The Wolf in the Fold

13 The Trap Closes

14 The Deal

15 Arms and Alarms

16 Progress and Precautions

17 The Battle of Lestiac

18 Maquis Officiels

19 Lencouacq

20 Of Missions and Machinations

21 Crossing the Frontier

22 Cyanide and Execution

23 Aristide Returns

24 ‘I come on behalf of Stanislas’

25 ‘Forewarned is Forearmed’

26 ‘This Poisoned Arrow Causes Death’

27 A Deadly Charade

28 The Viper’s Nest

29 Two Hours to Leave France

30 Nunc Dimittis

Epilogue: Post Hoc Propter Hoc

Acknowledgements

Dramatis Personae

Notes

Select Bibliography

Picture Section

Index

About the Author

Also by Paddy Ashdown

About the Publisher

EPIGRAPH

‘O look, look in the mirror,

O look in your distress:

Life remains a blessing

Although you cannot bless.

‘O stand, stand at the window

As the tears scald and start;

You shall love your crooked neighbour

With your crooked heart.’

It was late, late in the evening,

The lovers they were gone;

The clocks had ceased their chiming,

And the deep river ran on.

From ‘As I Walked Out One Evening’

W. H. Auden

INTRODUCTION

The three main characters of this book – Roger Landes, André Grandclément and Friedrich Dohse – appeared as fleeting shadows in my book A Brilliant Little Operation, the story of the ‘Cockleshell Heroes’ raid on Bordeaux in 1942. And that’s the way they would have remained had it not been for a chance email from a friend. Richard Wooldridge, who I had got to know while researching my Cockleshell heroes book, runs the remarkable little Combined Services Military Museum at East Maldon in Essex, of which I am a sometime patron. He had been gifted some documents which had come to light after the death of the owner of a house called ‘Aristide’ in Liphook, Hampshire. The papers had first been passed to a retired gentleman in the Isle of Wight, who asked Richard if his museum could provide a home for them.

Recognising the name ‘Aristide’ from the work we had done together, Richard contacted me and asked if I would be interested. I was, but, due to pressure of work could not visit the museum myself to look at the archive. So my colleague and collaborator in this book, Sylvie Young, made the journey to East Maldon and brought back around 400 photographs of letters and papers from the museum. It soon became clear that what we had was the personal archive of one of the Second World War’s most remarkable secret agents – Roger Landes.

And that is how this book began.

Since tracing Tito’s progress across the mountains of Bosnia (mostly on foot) and reading the remarkable accounts of F. W. D. Deakin and Fitzroy Maclean, who marched with Tito’s partisans, I have always been fascinated by that part of the Second World War in which Britain supported, fostered, and sometimes even created, bands of ‘freedom fighters’ (the Germans called them ‘terrorists’) dedicated to the liberation of occupied Europe.

Looking back today, it seems to me extraordinary that our besieged little country commited so many of its young men and women and so much of its resources to secret and extremely hazardous operations to free the countries of Europe, which we have now chosen to be no part of. It seems extraordinary that a nation which today does less than any other member of the European Union to help those fleeing the misery of war, was, so short a time ago, their only refuge. After the shock of the Referendum result, I still cannot bring myself to believe that our country, which has now turned its back on solidarity with our European neighbours, was then so much their last hope that, from the alpine pastures of Norway to the mountaintops of Greece, those desperate for freedom from every nation in Europe gathered on moonlit nights to listen for the tiny reverberation in the air which would tell them that the dark shadow of an RAF Halifax from London would shortly pass over them, with its largesse of weapons and its message that they were not alone.

Of course, I know that that is the romance of the story. I know that there is more to it than that. There are legends, and myths, and very black deeds – as well as brilliantly shining ones; and cowardice along with courage, and stupidity too, and vanity – a lot of vanity – and, it must be said, a good deal of betrayal as well. How could it be otherwise, since the basic ingredient of these stories is how ordinary, untrained, unsifted, unselected and unprepared individuals faced the great questions of life and death, which most of us have never had to face in our carefully pasteurised, cotton-wool worlds?

Fortunately, there is now a new mood amongst historians of the Resistance – and especially the French Resistance. A much more granular picture is emerging. The role of women is, at last, coming to light. The failures and betrayals are being analysed, as well as the triumphs, and a much more objective view about the overall achievements – and lack of them – is beginning to appear. This is especially so in France, where the fashion for debunking the Resistance may now even be distorting the picture in the opposite direction.

The role of organisations such as the Gestapo in the story of the European resistance movements remains, on the other hand, a monochrome black. Little has been written in popular form about how the Gestapo worked, how it fitted into the German hierarchy and especially about the individuals involved. In the popular imagination, Klaus Barbie – the ‘Butcher of Lyon’ – is the model for a Gestapo officer, and it is assumed they were all more or less like that. But of course they weren’t. It is time for a much more rounded description of what life was like then, not just for the secret agent operating in enemy territory, but also for the German security apparatus dealing with this so-called ‘terrorist’ threat, bearing in mind that in our age too we are faced with challenges which are, in practical terms even if not in moral ones, not totally dissimilar.

Following up on the leads in the Aristide archives, we stumbled across the fact that Friedrich Dohse, a Gestapo counter-espionage officer in Bordeaux, had written his memoirs (the only such ones in existence, I believe). These covered the period when his overriding priority was to catch British SOE agent Roger Landes. The opportunity now presented itself to write something which gave both sides of the story.

The third person in the triumvirate at the heart of this book is André Grandclément. He was responsible for one of the most controversial betrayals in wartime France. Much has been written on him, but little about his psychology and the deeper reasons for his ‘betrayal’ (if that, indeed, is what it was).

In this book I hope to give a picture of those times seen through the eyes of these three men – three enemies – who all lived and operated in wartime southwest France. In these pages, I trace their lives, almost on a day-to-day basis, over the two and a half years from the early months of 1942 to the final liberation of Bordeaux in August 1944.

This is not a book of moral judgements. The three men’s stories are presented, as far as possible, plain and unvarnished. Ultimately it is up to the reader to judge what to make of them. But if in the process of making those judgements, a more complete and detailed picture of this fascinating period and of some of the people who lived in it emerges, then this book will have achieved its purpose.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This is a work of non-fiction, based chiefly on primary historical sources. The key details of the story remain disputed even today. With very few exceptions the accounts which form the basis of this work were written shortly after the war, and often by participants whose reputations were at risk – either because they faced accusations of collaboration, or because they were subject to legal action. For instance, a principal source in this book is the unpublished memoirs of Friedrich Dohse, written while he was awaiting trial by a French military tribunal in Bordeaux after the war. These were plainly designed to put the Gestapo officer’s wartime activities in the most favourable light and form part of his defence against the charges he was facing. The same caveat must also apply to the descriptions of events given by others who, while not necessarily preparing for formal court cases, were nevertheless explaining their actions before the court of post-war French public opinion, or simply leaving a record for posterity. There are, in consequence, often radically different versions of the same event. In these cases, difficult judgements of historical evaluation have had to be made. Where an account exists which is substantially different to the one used in this narrative, this fact has been identified in the endnotes.

Sometimes it has been necessary to include some minor speculation in the narrative, where the basic facts surrounding an event have been already established. For example, on 24 September 1943, André Grandclément rode a bicycle through Bordeaux to pay a clandestine visit to the house of Charles Corbin. A visit to the Corbin house for research revealed that the building is very small with a tiny back garden and no back access. Based on these facts and bearing in mind that Grandclément was paying a secret visit to the Corbin family, it seems reasonable to speculate that his bicycle would have been wheeled through the Corbin house into the back garden, rather than leaving it outside.

The dialogue in the Prologue has been reconstructed in a manner consistent with the known facts of the event described. On all other occasions dialogue has only been included where it was either recorded at the time, recorded later by one of the protagonists, or subsequently verified as an accurate representation of what was said.

There are also some important issues regarding terminology. The term ‘Gestapo’ originates from the first letters of the three words used for the Nazi state secret police (GEheimeSTAatsPOlizei). But the ‘true’ Gestapo was only a small element within the overall, highly complex German state security apparatus. However, the Gestapo gained such a reputation during the war that very soon (and with the active encouragement of SOE) the word ‘Gestapo’ became a generic word used to cover all parts of the German security system. In an attempt not to test the sanity of the reader too far with unnecessary complexity, the term ‘Gestapo’ in this narrative is, in almost all cases, used in its wider more ‘popular’ sense, rather than its narrower more technical one.

In the 1930s and 1940s the term ‘spy’ carried pejorative overtones of cheating and underhand activity which it does not have today. For this reason – and perhaps also in the vain hope that their operatives behind enemy lines might gain some flimsy protection from the Geneva Convention provision that spies could be shot – the Special Operations Executive was very particular not to call its operatives ‘spies’, but ‘secret agents’. However, any such distinction was rejected by the German authorities at the time: they ignored SOE’s terminological niceties and treated all their captured agents as spies, liable to immediate execution.

In addition to one or more false identities with which every SOE agent was equipped, each also had a number of aliases or codenames: one which was used under training, another for SOE files and correspondence, and a third for when they were in the field. For example, Roger Landes’s false identities in France were ‘René Pol’ on his first mission and ‘Roger Lalande’ on his second. Under training he was known to his colleagues as ‘Robert Lang’; the internal alias by which he was referred to in SOE papers was ‘Actor’ (all F-Section agents had internal aliases based on occupations) and the nom de guerre by which he was known to his French colleagues was ‘Stanislas’ on his first mission and ‘Aristide’ on his second. In addition, SOE agents often accumulated nicknames while in France: Victor Charles Hayes, codename ‘Printer’, alias ‘Yves’, was more frequently known to his French colleagues as ‘Charlot’ – or, because of his prowess with explosives, ‘Charles le Démolisseur’. Although almost all the participants in this story would have used their aliases when communicating with each other I have used personal names throughout, except where the needs of the story dictate otherwise (for example, when it is appropriate to refer to Roger Landes by the noms de guerre by which he was known to the Gestapo officer Friedrich Dohse – that is, ‘Stanislas’, and later ‘Aristide’).

During the war, the French resistance, diverse and diffuse as it was, was neither referred to nor seen as a single body. It was only after the war that the disparate resistance organisations were regarded as part of a single overarching structure known as the French Resistance (with capitals applied to both words). For ease of reading, I have, in this book, adopted the post-war habit of referring to the French Resistance (with capitals) when referring to the overall organisation, and French resistance when the noun is employed more generally. Latitude and longitude for places of key importance (such as parachute sites and places of execution) are included in the endnotes. For certain military operations, timings are given according to the twenty-four-hour clock and have been converted into Central European Time (Greenwich Mean Time plus one hour from 16 August to 3 April, and GMT plus two hours from 4 April to 15 August) – which was the standard time used throughout all Nazi-occupied Western Europe for the duration of the war.

As is often the case, there are a bewildering profusion of characters who people this historical narrative. In an attempt to make things easier for the reader, I mention characters by their names only if they appear more than once. For those interested in the names of the others mentioned, these, where known, can be found in the endnotes. Even so, the reader may find the number of names challenging. I have therefore provided a dramatis personae of all the main characters.

PROLOGUE

THE EXECUTION

The man’s index finger slid forward along the cool metal surface of the Colt in his overcoat pocket and curled gingerly around the trigger. The signal would come soon now.

The young woman walked half a pace ahead of him and a little to his right: she was lithe and pretty with auburn hair. Her wooden-soled sandals clacked on the dry path, and her wedding ring glinted in the last rays of the evening sun. She had dressed for London carefully, before leaving the house: slingback sandals with raised heels, a deep V-neckline green dress, which swung on her hips as she strode lightly along the forest track. She was happy: by the morning she and the husband she adored would be far away from this snake pit of betrayal and treachery.

In a few moments he would have to kill her. He had agreed to this when they had decided on the executions an hour previously. He had not killed before – though he had ordered others to be killed. But he was calm. It had to be done and he was ready for it.

On the woman’s right walked a second man, his hands too plunged deep into the pockets of a heavy coat, though it was a warm summer’s evening.

They strolled along the track, between the fir trees, chatting amiably.

‘When will the aircraft arrive?’

‘After dark I suppose. We’ll hear when we get to the landing site.’

‘How long will it take?’

‘To London? About three or four hours I should think.’

‘Oh! As long as …’

The sentence died in a cacophony of shots and screams coming from the other side of a small copse to their left.

With a flick of the wrist, the Colt was out of his pocket, its muzzle pressed against the back of the woman’s skull. He pulled the trigger. But it wouldn’t yield. In the millisecond it took him to push the safety catch down, the woman, feeling the cold of the muzzle, turned her head. He could already see the flared white of her left eye and the terrified gape of her mouth when the gun fired. She dropped silently to the ground, a crumple of green and red lying incongruously on the forest path, as his shot echoed through the woods, startling a small cloud of evening birds.

They half-carried, half-rolled the woman’s body into a stream, which ran quietly in a nearby ditch. Her fresh blood billowed in the clear water.

They were joined by two men half dragging another corpse, which trailed a wide smear of blood on the woodland path.

‘Both dead?’ the man with the Colt asked.

‘Yeah, but Christian botched the young man. I had to finish him off. He shouted for mercy.’

‘Put him in the ditch and we’ll collect the other. The guys will clear up in the morning.’

Ten minutes later the two men’s bodies lay heaped in an awkward jumble on top of the woman’s. Their blood mingled with hers, turning the little rivulet into a meandering of crimson among the grasses and ferns.

They covered them with branches, walked back to their vehicles in the gathering dusk and drove to Bordeaux, arriving just before the start of curfew.

1

BORDEAUX – BEGINNINGS

After Paris, probably no French city was more affected by the drama of the fall of France and the early months of the German occupation than Bordeaux.

On 10 June 1940, with the sound of German artillery ringing in their ears, the French government fled Paris. Four days later they set up their new emergency wartime capital in Bordeaux. As newcomers, they were not alone. The city was already bursting with a vast tide of humanity, which the French christened the Exode – the great exodus of refugees desperately fleeing south to avoid the advancing German armoured columns.

Historically this was not a new experience for Bordeaux. Twice before the city had acted as the emergency capital and chief refuge of France: during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and again in 1914. But everyone sensed that this time was going to be different. This time it was going to be not just a military defeat, but a national catastrophe in which all would be engulfed.

The last scenes of France’s tragedy were swiftly acted out.

On the evening of 16 June 1940, General de Gaulle, who had been sent to London to secure the support of the British, flew back to Mérignac airport outside Bordeaux in a plane which Churchill had placed at his disposal. He booked into the Hôtel Majestic and arranged an urgent interview with Marshal Pétain, who was headquartered next door at the Hôtel Splendid. The interview was short and fruitless. De Gaulle promised Churchill’s help and pleaded with the old marshal to begin the fight back. But it was too late; the die was already cast. Later that day the French prime minister resigned and Marshal Philippe Pétain, the hero of Verdun in the First War, began negotiating an armistice with the Germans. Disgusted, de Gaulle returned to Mérignac and, on the morning of 17 June, took off for London accompanied by four clean shirts, a spare pair of trousers, 100,000 gold francs and the honour of France. The day after, he made the first of his great speeches from the British capital, appealing to all French men and women to rally to his cause and rescue their country from the shame of defeat.