Полная версия

Clever Dog: Understand What Your Dog is Telling You

CLEVER

DOG

Understand What Your Dog is Telling You

Sarah Whitehead

Dedication

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction: Dogs and dinner parties

Part 1: LIFE

1 - Dominance: The wolf legend and other myths

2 - Canine communication systems: Learning the lingo

3 - Team building: Stress immunisation for your puppy

Part 2: LOVE

4 - Emotions and addictions: Dogs who love too much

5 - Relationships: How your dog sees the world

6 - Sociability: Choosing the perfect dog for you

Part 3: HEALTH

7 - You are what you eat: The effects of diet on behaviour

8 - Stress and anxiety: On the couch

9 - Sex: Hormonal hounds

Part 4: HAPPINESS

10 - Life with purpose: Going with the flow

11 - Protection and connection: Park life

12 - Learning: What gets rewarded gets repeated

13 - Training in a foreign language: ET come home

Conclusion: A dog by my side

Bibliography

Fabulous websites

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

Dogs are a household subject and one – it seems – on which everyone has a fascinating opinion. Numerous dinner parties attest to this. There I am enjoying a nice glass of Chablis and a friendly chat when someone asks what I do for a living. I’ve never yet said ‘I’m in IT’ but I may well consider it in future because no sooner have I confessed that I’m a pet behaviour specialist than someone comments: ‘Ooh, that’s great. I have a dog you could help with.’

At this stage, of course, they don’t really want my help – they just want to talk about Bonzo’s latest naughty adventure and, frankly, I love a good dog story. Once they are done, the comments from the other guests are revealing. Having heard how Bonzo bites people, runs off, barks all day or eats the carpet, someone will always say, ‘I know how to stop him doing that’ – and that someone is never me! Invariably, the ‘expert’ will proclaim the most hideous, punitive measure to be a complete and universal cure. Apparently, it’s OK to suggest to a complete stranger that they use an electric shock collar on their dog, that they should rub their dog’s nose in faecal matter or that they should strangle the poor thing on a choke chain, all in the name of training. Uh oh.

At this point in the conversation, there’s a small pause. The circle of guests stop and turn to me. ‘So, what do you think of doing that?’

Pass another glass of wine, please, and make it a big one.

Strong opinions on dog behaviour are not confined to the social scene. Over the years, I’ve appeared as an expert witness in court cases where the magistrates have, quite literally, the power of life or death over someone else’s pet. These cases are often depressingly complex, costly and time-consuming, and yet, all too often, after I’ve given evidence on a specific behavioural aspect, the magistrate will say something along the lines of: ‘Thank you, Ms Whitehead, but I think we know how dogs behave.’

My work as a pet behaviour counsellor has kept me busy, impassioned, fascinated and laughing for the past twenty years. In that time, I have had the honour of meeting thousands of dogs and owners across the UK and internationally, and have relished the chance to ‘talk dog’ with them. I now specialise in aggression problems and the more weird and wonderful behaviours dogs can present, while my practice deals with every kind of canine behaviour problem that you can think of – and then some. Working on referral from veterinary practices around the country, we are constantly in touch with the practicalities of canine training and behaviour – and still, after all these years, I love every minute of it.

Perhaps the fact that dogs are so common in our culture works against them. They pervade our domestic existence and yet they are remarkably under-researched. Want to find out about dog behaviour? Nine times out of ten you will be forced to read literature on wolves, studies on rats and research on pigeons. This is the equivalent of studying human psychology by examining the behaviour patterns of the great apes. It may be interesting and relevant, but it isn’t the same as studying the actual species that we live with day in, day out.

Maybe the scarcity of rigorous scientific research on domestic dogs is the reason why so many myths about their behaviour pervade our society. In many cases, these myths have become so ingrained that we accept them as truth, never questioning where they came from or how factually correct they actually are. In this book, just as in my everyday work as a pet behaviour specialist, I will propose some new ways of thinking about dogs. Some of these may be thought-provoking, some even shocking. In an age when we are all too often blinded by the ideas we are fed by television, the lures of urban myth and the promise of a fifteen-minute fix, it’s all too easy to think about dogs from a purely human perspective. Instead, perhaps now is the time to think about life from the dog’s point of view: to let go of all the previous theories that you have toyed with, to open your mind and, as my mentor the late John Fisher always said, ‘Think Dog’.

Case history: Ice, the misunderstood Malamute

‘This is a wolf you are dealing with here!’ barked the training instructor. ‘You need to show him who’s boss.’ With that, the big man strode across the room, grabbed the lead from the humiliated owner who had been struggling to get her dog to sit, and strung him up so that his front feet were off the floor.

At eight months old, Ice, the big, grey-and-white Malamute, had never been treated like this before and did what any reasonable dog would do when it thought its life was under threat: he became very still, averted his gaze, and uttered a long, low warning growl from deep in his throat.

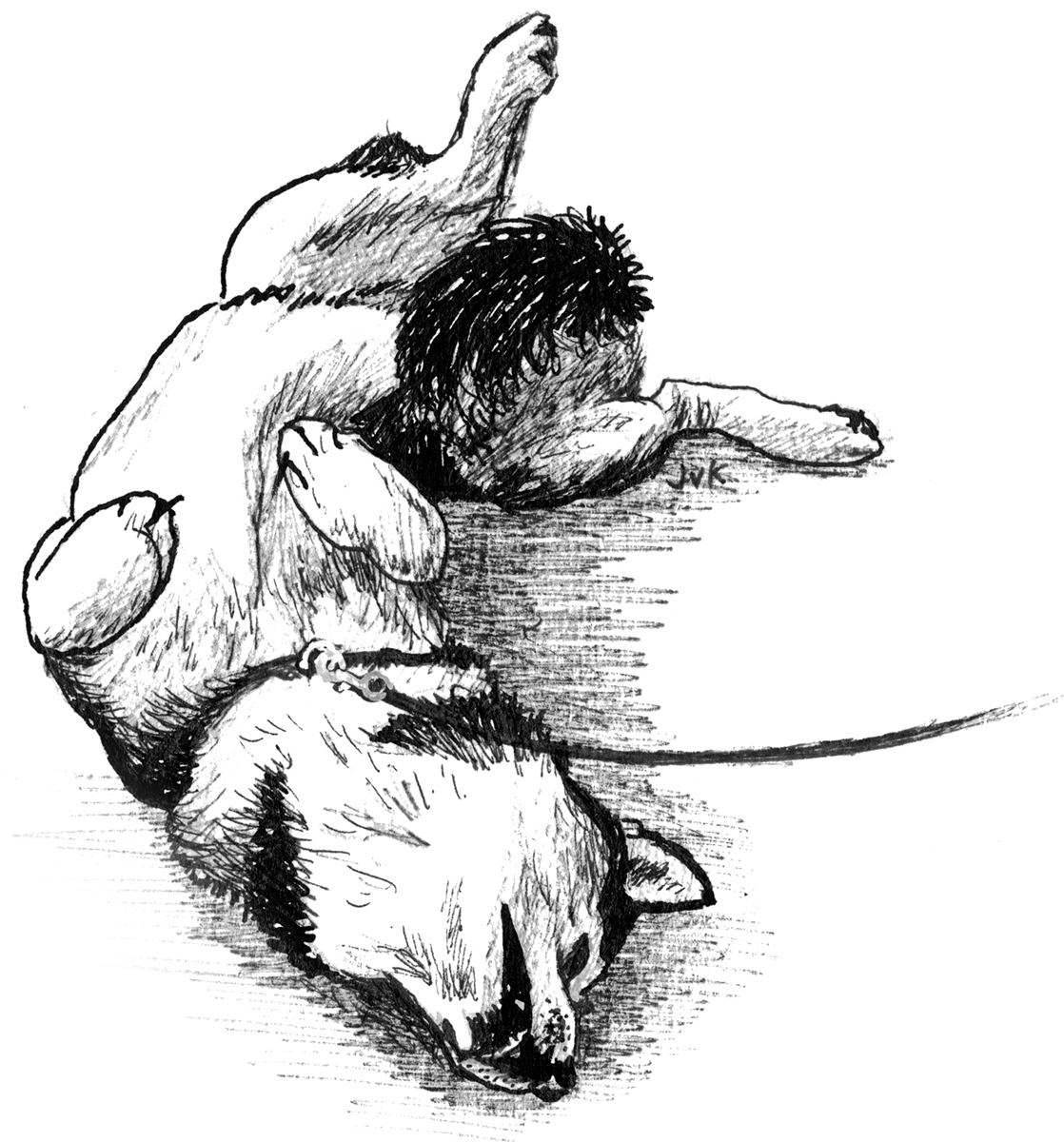

‘No dog’s gonna growl at me,’ stormed the instructor, and with one swift movement he launched himself at the dog and managed to wrestle him to the ground and onto his back. Ice wet himself in fear.

‘There,’ said the trainer. ‘He’s submitted.’ He got up and wiped the urine from his sleeve.

Ice stayed where he was, lips drawn back and tail curled defensively under his belly.

‘Now, you need to do that every day,’ said the instructor. ‘It’s called an alpha rollover. It’s what the pack leader would do to the other wolves in the pack to keep them submissive. You need to act like a pack leader, and doing this exercise every day is part of it. OK?’

Ice’s owners, Keith and Sharon, nodded in quiet agreement. They took back the lead and sat down at the side of the hall with a very subdued dog by their side. It wasn’t nice to see their pet being manhandled, but it did seem to have an effect on him. After all, he was a big, powerful dog – Malamutes may look like Huskies, but they are bigger and stronger – and he had started to pull them towards strangers in the street. They knew that they couldn’t allow him to become out of control.

Keith and Sharon did their homework every day as instructed – or at least they tried to. Over the following week, they subjected Ice to repeated ‘alpha rollovers’. The first day, Ice seemed to think it was a bit of a joke. He took Sharon’s arm in his mouth and held it as if he was playing, but she persisted and forced him onto his back. He lay there looking bemused, and jumped up again as soon as she let go. On the second day, things weren’t so easy. As Sharon approached, Ice dodged out of the way and tried to flee the room. Between them, Keith and Sharon caught the huge dog and pinned him down, but he growled continuously and Sharon was sure he tried to snap as they let him get up. By the Thursday – you’ve guessed it – Ice was having none of it. He had tried every trick in the doggie book to get his owners to stop behaving so weirdly and his patience had run out. When they approached him, Ice bared his teeth and snarled so ferociously that Sharon was genuinely frightened; Keith probably was as well – and who could blame him? They decided to leave Ice alone.

The next night, they were back at the dog training class. For the first time since joining the class a few weeks before, Ice stiffened as he entered the hall and growled at a lady who reached out her hand to stroke him. This took Keith and Sharon completely by surprise, as he had always been friendly with the other owners before. The fray attracted the attention of the instructor who came stomping towards them, red in the face and looking as though he meant business. This time, however, Ice was ready for him. As the instructor leant forward to take the lead from Keith, Ice saw his opportunity and lunged at him, teeth on full display and barking (well, spitting) with full force. Unfortunately, at this point the instructor made a terrible mistake. Instead of backing off, turning away or reducing the level of threat he was showing the dog, he moved towards him, determined in his own uniquely human way to have the last word. His lesson was a clear one. Ice bit him on the arm. With Sharon in tears, Keith shaking with adrenaline and Ice in disgrace, they were ordered to leave the hall, the instructor’s final words ringing in their ears: ‘That dog is out of control. He’s dominant and aggressive and you should have him put down. If you don’t, I’ll report you.’

Keith and Sharon sat on the sofa in their front room as they relayed this sorry tale to me. Pale and anxious, they frequently glanced at each other for reassurance, clearly worried about what I was going to say. They feared they were going to lose their precious dog.

Sadly, this is a story I am all too familiar with, in one form or another.

It’s so tempting to believe the traditional story: a caveman tames a wild wolf and they both live happily ever after. However, this myth fails on so many counts that it’s a wonder it has prevailed for so long. Domestic dogs are not simply tame wolves. Nor do tame wolves ever become ‘domestic’, no matter how well they have been hand-reared. Although dogs and wolves share a genetic background, failing to distinguish between the two species is as misguided as failing to distinguish between man and ape.

So, how did such myths come to be so prevalent in our society? Why is it that so many books, television programmes and self-styled ‘experts’ are still claiming that dogs are really the ‘wolf on your sofa’?

Many of the tales told about wolf behaviour are simply untrue. The idea that the alpha pair always eat first is one example. If this were truly the case, how on earth would wolf cubs survive? Such a claim simply doesn’t make evolutionary sense. The fact is that wolves are highly social and a kill is shared amongst the pack – with youngsters, adolescents and even elderly wolves getting a good meal, often before the other adult members of the group.

Other theories – such as the idea of a linear hierarchy – where a strict ladder of rank exists – are based on captive packs. However, keeping any kind of predatory animal in a restricted area with others of its own kind is a far cry from ‘natural’ behaviour; we only have to watch the Big Brother television show to appreciate that!

Even the idea of submission has been woefully misinterpreted. Wolves living a free and wild existence don’t exert dominance over each other in order to elicit submission; on the contrary, submission is offered freely by one wolf to another in order to gain reassurance – something quite different – and it’s a behaviour that’s not shared by their domestic cousins, the dog. Indeed, wolf cubs raised with domestic dogs sometimes illustrate this in the oddest ways, with the cubs trying to push their muzzles inside the jaws of their rather bemused domestic dog elders.

While some of the misinformation that exists about ‘wolves versus dogs’ is simply amusing, in my role as a canine behaviour specialist, I have first-hand evidence of the problems such ingrained and unquestioned beliefs can cause. The idea that dogs view humans as a part of a pack, and that they must observe pack rules in order to be ‘leader’, has led to some extraordinary urban myths. These include encouraging owners to sit in their dogs’ beds to show them who’s boss, and telling them to ignore their dogs when they first come home in case the dog tries to ‘dominate them’. Owners are asked to pretend to eat before feeding their dog in a misplaced effort to show the dog he’s bottom of the pile. Some even follow the advice to pin their dogs down, in a so-called ‘alpha rollover’. What dogs think of these appalling misjudgements of their communication systems is anyone’s guess. How they put up with these bizarre human ways is even more of a mystery, but to me, the greatest travesty is that very few people stop to question the rationale behind the rules they are given.

So, if dogs are not wolves in disguise, what are they? Well, there is strong evidence to suggest that dogs are just big babies! Instead of developing into full-blown adult wolves, evolution has caused a genetic shift, bringing about both physical and behavioural changes. Domestic dogs’ skulls are smaller than wolves’, their teeth are relatively undeveloped and their reproductive cycles are different. Domestic dogs yelp, they whine and they bark – all characteristics that are lost by the time a wolf is five months old. In other words, dogs stay for ever as juveniles – playful, puppy-like and highly dependent on their parents.

Dogs and humans share a long and successful history together because of the ability to get along, and because they need us. This sociability is based on good communication (dogs are great at this, while we do our best), the ability to share (a juvenile attribute) and teamwork. Just watch a sheepdog and his handler work, or a Retriever in the field, fetching birds back to the gamekeeper. They are not in competition with each other but are operating as a team, each with different but equal skills.

Perhaps my greatest challenge when working with pet dog owners is to get the message across that your dog is not an adversary but an ally. Work together and the team will build bonds so strong they will never be broken. Work against each other in the belief that your dog is trying to dominate you, and the relationship will start to suffer.

During the whole time that Sharon, Kevin and I were chatting, Ice lay on the floor looking nonchalant, as only a Malamute can. He was one of the most beautiful dogs I have ever seen, with ice-blue eyes (hence the name), a thick, plush coat and a face that you just wanted to snuggle into. However, every time I so much as moved my hands, he became still and rolled his eyes slightly – a clear and perfectly polite canine communication warning me to keep my distance.

Since I’d entered the house, Ice had kept a careful eye on me. He was not proactive and as long as I held back, I knew I was going to be safe around him. He just needed to know the same about me. It was little surprise that Ice thought I was likely to be bad news. Ever since the training class incident, Keith and Sharon had received few visitors, and had taken to walking Ice in the early hours of the morning so as to avoid other people, fearful that he would act aggressively and force them into making a final decision. Poor Ice had been kept a virtual prisoner in the home, and although he was well cared for, his owners had been ‘tip-toeing’ around him, fearful of what he might do next.

As in many such cases, the road to success would require a careful combination of planning and action. Ice desperately needed an active social life in order to re-establish his social skills with other people and other dogs. But in the early stages, my uppermost goal was to build the family’s confidence in each other once again. We started with some basic training. Training is often under-rated in these situations, but it can be the glue that holds the family together while relationships are reformed. Thankfully, training these days can be fast, fun and friendly. Gone are the days of ‘stomp and jerk’ techniques. Indeed, what we know now is how much faster dogs learn if they are encouraged to use their brains rather than brawn. Nowadays, there are many enlightened trainers and instructors out there who are using behavioural understanding to underpin their training – a far cry from the outdated techniques that poor Ice had been subjected to.

Ice was a fast learner. With the help of some tasty morsels of cheese, we had him sitting up and (quite literally) eating out of my hand within minutes. Having motivated him to want to engage in some fun interactions with his owners, we encouraged him to sit, lie down and give a paw on command. We finished with a finale of ‘be a bear’ – a great trick in which the dog sits up in a begging position and looks as cute as cute can be.

Inspired, his owners were given two weeks to practise these new behaviours. Ice was to be engaged in ‘fun training’ twice a day, using food and a relaxed approach, and was to get used to wearing a special head collar so that his owners could take him for a walk without being towed along behind him. Head collars allow almost complete control, like power steering, and make perfect sense in cases where the owner needs to avoid getting into a battle of strength with a big dog, who is clearly going to win. After all, no one would consider walking a horse on a piece of string. This bit of kit made all the difference to Sharon, as she could walk Ice with confidence when using it.

After two weeks of indoor practice, we were ready to hit the streets – and it didn’t have to be at two o’clock in the morning either. Poor Keith and Sharon had lost so much confidence in their ability to handle their dog that we formulated a programme of ‘stop on sight’. This meant that every time we saw someone walking our way, we asked Ice to give us attention, stop and sit. How, you might ask? Through good, old-fashioned bribery. In fact, this is not the ‘giving in’ that many people think it is. In the first few instances when Ice saw someone heading towards him, we simply showed him that we had some delicious chunks of cooked chicken on offer. This immediately produced the desired result, However, the next part was pure magic.

Imagine you have been summoned to see the boss. Generally, when this happens it’s not good news. As you walk towards his or her office door, you start to feel a little anxious, your palms get sweaty and you begin formulating defensive arguments in your head to stave off possible attack. However, when you go in, your boss greets you with a big smile and holds out his hand to congratulate you. You have earned a bonus. He gives you £1000 in cash on the spot. You are overjoyed! On the same day the following week, you are once again called to the boss’s office – and the same thing happens all over again. Unbelievably, this is repeated a third time, at the same time and on the same day of the week. Now, just imagine how you feel going into work in the fourth week. Are you elated? Full of hopeful expectation? You bet! Rewards that are linked to circumstances (days of the week, visual cues, people) have the power to affect your emotional state, not just your behaviour.

With this in mind, we worked on the equivalent canine scenario, and watched as Ice made giant conceptual leaps. During the following six weeks, the appearance of someone walking towards him in the street prompted him to whip round, sit down and look up at his owner, without having to be bribed, cajoled or reminded. Even better, he even started to offer ‘be a bear’, which elicited smiles and laughter from those walking past where they might once have given him a wide berth. These new responses were heavily rewarded. We played with Ice in the park, the street and in the communal front garden of his owners’ home. We gave him chicken, dried liver, hot dog sausages and fish treats for being calm and social around new people both inside and outside his home. We praised him for good behaviour and ignored it when he got it wrong. It worked like a dream. Within three months, without any drama, pretending to be Alpha leader, punishment or Alpha rollovers, Keith and Sharon found themselves back in control – and completely besotted with their lovely dog again.

TOP TIPS ON BUILDING A GREAT RELATIONSHIP WITH YOUR DOG

» Work on building a trusting relationship with your dog. Don’t assume he is trying to challenge you for ‘leadership’. The best dog/owner combinations are teams, not competitors.

» Start as you mean to go on. If you don’t want your huge, muddy dog getting on the sofa when he’s three years old, don’t let him do it when he’s twelve weeks old – no matter how cute.

» Start training early, the second that you can – especially with big breeds. The old adage that you can’t start to train a dog until he’s six months old is wrong. Just think how much easier it is for children to learn a new language than it is for adults.

» Be consistent. Agree rules and boundaries within your family – and stick to them. Write them down if it will help to avoid domestic arguments later. Dogs like to know exactly what they can and can’t do.

» Choose a training class that uses kind, fair and effective methods. The days of choke chains and ‘yank and jerk’ training are long gone.

» Use brain, not brawn. If your dog tries to manipulate a situation by engaging in a battle of strength, immediately disengage and use your superior intellect to defuse the situation. Many dogs enjoy physical confrontation – so you will ‘win’ by refusing to compete in this way.

» Replace negative commands with positive ones. For example, ask your dog to sit rather than nagging him not to jump up.

» Clicker training is a great way to teach dogs new tricks that can have an effect on their emotional states and the way they behave generally, not just their immediate actions. They also impress humans.

Clicker training is fast, fun and kind, and can be used in all sorts of ways. The clicker – a small plastic tool that makes a double click sound when pressed, effectively acts as an ‘interpreter’ between human and animal, marking the behaviour that earned the reward, and making the whole learning experience one that is focused on trial and success, rather than trial and error. This, of course, has an impact on emotion, too. I know how my dogs look and behave when I get out the clicker to do some training – it’s the highlight of their day, and it also has the effect of making me feel happy, too. Want to try clicker training but don’t know where to start? Find a good instructor or class at www.apdt.co.uk or watch easy-to-follow demos on the Internet. My favourites are www.trainyourdogonline.com and www.clickertraining.com, where Karen Pryor demonstrates by training a fish. Try it for fun – you’ll be amazed what your dog can do.