Полная версия

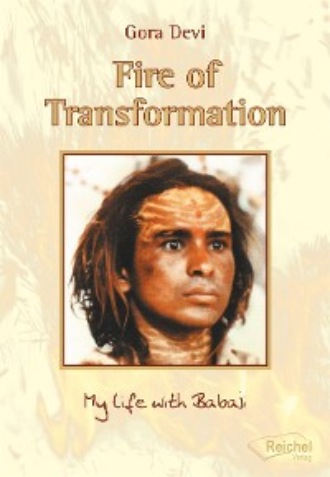

Fire of Transformation

When I entered Babaji's temple, I caught sight of Him immediately, seated on His dais, dressed in white, always so beautiful, unreal, etheric, radiant. He called an Indian man over and told me to accompany him to the bazaar to drink a large glass of milk taken from a huge terracotta vessel. I am amazed to be in such a wonderful place and I don't feel afraid any more, I feel secure, embraced by Babaji's love and the warmth of the people around me.

In the evening, when I sit in the temple, the Indian women and the children come up close to me and appraise me with great curiosity. They look at me, touch me, they caress me, admire me: to them I am the woman with a white skin and they make me feel very beautiful. Babaji called me over and told me that my name is Kali, the warrioress, the Black Goddess, but then immediately afterwards He changed His mind and said with tenderness: 'No, your name is Gora Devi,' which means, they told me later, the White Goddess.

I am particularly moved by the music and the songs, by Babaji's splendour and the devotion of the Indian people. They stand in a long queue holding garlands of flowers in their hands as an offering, then place them around His neck before they pranam to Him and receive a gesture from Him, a smile, a word or some prasad, blessed food.

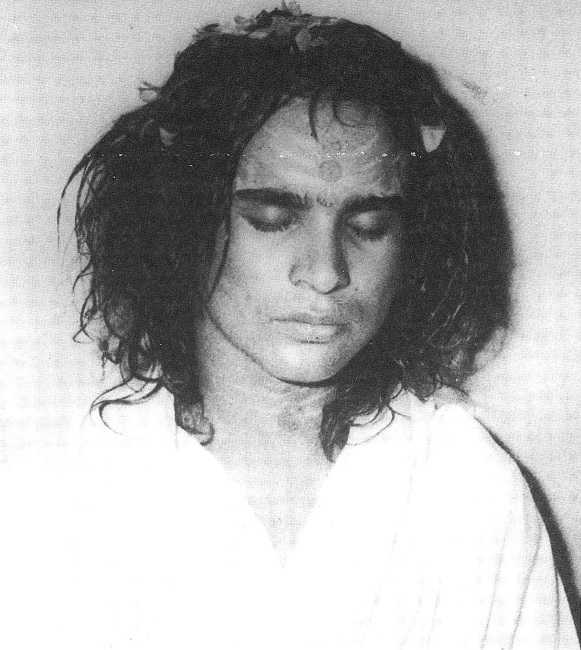

I also stand in line and I feel extremely emotional just by coming in close proximity to Him. An energy of great intensity emanates from Him and I experience an incredible sensation, sensing as well that He can read all my thoughts. His eyes are magnetic, shining, full of love, strength and knowledge. I never become tired of looking at Him and notice that everybody else does the same. For two or three hours Babaji continues to sit virtually motionless. He doesn't speak, doesn't do anything, He just makes Himself visible for us to contemplate and adore; He gives darshan, which Indian people explain to me as being a vision of the Divine in a human form.

The impact of this experience touches everybody in an intimate way; I can see it in people's eyes and from the energy in the temple. People sing continuously, sometimes Babaji's mantra, 'Om Namah Shivaya', sometimes other devotional songs, until late in the evening.

At night we sleep on the roof of a small building constructed next to the temple, lying on a straw mat, the place surrounded by monkeys. It is still dark when we are woken up at four o'clock in the morning as devotional chants begin resounding from all of the temples in the city, more than seven hundred of them. After a shower I meditate in a corner for a short while, then we go to the temple for the aarati, morning prayers. We wait with trepidation for Babaji's arrival, for Him to emerge from His room and be seated on the modest dais prepared for Him. The temple is extremely clean, full of flowers and smelling of sweet incense.

We don't have breakfast or dinner, only a large lunch, as well as pieces of halva and fruit that are distributed during the day. Some people continue singing until late in the morning, other people work, either cleaning, washing, cooking or carrying drinking water from the well that is situated in the square opposite the temple. Babaji often speaks with individual people, just a few words here and there, very quietly, softly. After lunch everybody has a short afternoon nap and at about five o'clock we bathe and meet again in the temple, in order to clean and prepare everything for the evening worship.

In the afternoon many people choose to go to the river to bathe, in the Jamuna, a river sacred to Lord Krishna. In the evening the aarati ceremony is performed again and afterwards people sing until late in the night, beautiful, sweet songs. I don't understand the meaning of the words, but I surrender to the melody, to the feeling of a divine dimension.

It's tremendously difficult for me to adjust to the daily routine and to the strict discipline, to the Indian capacity for hard work, particularly because the weather is extremely hot and it makes me feel tired. The month of May is torrid in India, an especially oppressive time of the year and I often escape to the bazaar to find something cool to drink, even if I know that Babaji doesn't approve of it.

Babaji - '...dressed in white, always so beautiful, unreal, etheric, radiant.'

15 May 1972

I am beginning to find it difficult to withstand the way of life here. The daily routine is tiring, monotonous and some of the young Indian men are very brusque and treat me badly, they don't allow me to work with them and they treat me as if I am a stranger. Babaji always fascinates me, but even He keeps me at a distance, is unapproachable. It is almost impossible to communicate with anybody, since I don't know Hindi and can speak only a few words of English.

In this intense heat I always feel thirsty but the water from the well is tepid and a little salty; it does not quench my thirst. When I bathe in the river, which is cloudy and muddy, it leaves me with a strange sensation and I don't really feel clean after washing. In the morning I have to wait in a queue for an interminable length of time in order to be able to take a shower in the guesthouse. In the evening in the temple, everybody is sweating, the temperature rises to more than 40 degrees centigrade, it's sweltering but Babaji seems totally indifferent, not sweating Himself.

In Vrindavan there are hundreds of ageing widows all dressed in white saris, who live all together in various temples. They pray continuously, accompanied by the sound of small cymbals and other instruments. Some of the old women are extremely poor, their saris white-grey, and they ask for alms. It reminds me of a scene from Dante's Purgatory. People explain to me that in India a widow cannot marry a second time; she has to renounce the world, she loses her home, her possessions and spends the rest of her life in prayer. It seems extremely cruel to me and ironically I remember the women's liberation movement in the West. I start to feel restless and a strong sense of nostalgia arises in me to see my Western friends again in Delhi; I ask Babaji if I can go away for a while and He allows me to leave.

* * *

New Encounters

Delhi, 18 May 1972

I have started to travel around on my own without any fear or uneasiness. The other day, while waiting for a train in the railway station, I spread a piece of cotton on the platform like the Indians do and I sat down patiently to wait, using the time, as they do, to contemplate life and myself.

Railway stations are meeting places in India, joyful and familiar, and people talk to each other all the time. The Indian people regard me as a curiosity, they ask me where I come from, why I have come to India, what I am looking for. They are surprised that I have left the West, which in their minds is a paradise of material comforts, in order to come here and share their poverty. Some of them ask me if I am looking for mental peace, invite me into their homes, offer me food and shelter, all with a great sense of hospitality and humanity. In India to be hospitable is regarded as a sacred undertaking and people offer it with much warmth, their eyes gentle and full of love.

21 May 1972

I have been in Delhi for a few days and I feel comforted by the city. In old Delhi, in the Crown Hotel, I meet up with my friends again, Piero, Claudio, Shanti and some other people recently arrived from Italy. The hotel is on three floors, old and dirty, but rather grand in its way and from the terrace there's a commanding view of the railway terminus in the old part of the city. It's also the crossing place for numerous roads, the point of departure for numerous destinations, the location of many Hindu temples alongside Muslim mosques. It seems like the meeting place of different civilizations, India, Muslim countries, the West, China, and Tibet. Down on the streets there's a continual movement of people, rickshaws, horses, carriages, cows and cars, there seems no end to it all. Cows are regarded as holy and are shown great respect, so if they decide to cross the road the traffic comes to a standstill.

Many Westerners are camping out on the big terrace as well as occupying the small, hot, humid rooms where they keep the fans on all the time. As in Bombay, people smoke a lot and consume large quantities of fruit juices, tea and sweetmeats, taking numerous showers to fend off the heat. It's not a beautiful or a comfortable place, but it has a certain magical charm despite the dirt and chaos, not least because there are people here like me, searching for truth, ready to risk everything, to suffer, even to go so far as to lose themselves completely for the sake of this spiritual adventure.

People come and go all the time, exchanging news, addresses, tricks for acquiring visas and how to survive in the jungle of the Indian city. Many of them have found Indian or Tibetan teachers and I also talk to them about Babaji and His beauty. I show them photographs of Him and as usual Shanti teases me saying I am only attracted to Him because He is young and beautiful, but it's not like that at all. Later on Shanti proposes that I visit one of his teachers with him, a Dr. Koshik, who is an ordinary man, married with children, but who is very wise and enlightened. He is a disciple of Krishnamurti, who doesn't favour the cult of the guru, or their rituals and mantras; I decide to go.

23 May 1972

Shanti continues to question me and asks what Babaji is teaching me. I have some difficulty in explaining it to him: about singing the mantra I say, and to wake up early in the morning to pray. Suddenly I recall what happened one day in Vrindavan. It was late in the morning, the temple had become empty and I realized that only Babaji and myself remained there, alone together. Immediately I panicked and felt extremely nervous. Then Babaji suddenly called me to sit with Him and we sat in silence. I was aware of my mind continuously active, frenetic, unable to make it stop, when Babaji told me to repeat Om Namah Shivaya. I tried, but even to repeat the mantra seemed impossible, artificial. Then all of a sudden my mind stopped for a few seconds and I experienced a strange calmness; Babaji gave me a broad smile and stood up. In that moment I sensed a silence inside me and realized the completeness of what Babaji had been teaching me. When I recounted what had happened to Shanti, I could see that he was impressed; he told me that, in effect, this experience of silence is what every master tries to impart.

It's incredibly hot and we spend almost all day in the hotel, only going out in the evenings. Living here is incredibly cheap and so we feel wealthy, going out to dine in different restaurants, travelling by taxi, buying clothes. But I am learning to understand many things, including for instance to accept the idea of poverty, which has a dignity over here. It's respected and even appreciated, because it's close to simplicity. In the Western world life is based on competition and arrogance, on the ego, and the poor have no place in society, neither do those who are old or infirm. In India there is room for everybody, including us crazy freaks. India has always had a capacity to accept different religions and traditions with a great deal of tolerance. The caste system is still present, it's true, but it also exists in the West, in a hidden way: the rich and the poor have an entirely different place and role in society. India is open to everybody, like a great mother and it is especially open to the spiritual pilgrim. It's like an ocean where many rivers merge from different civilizations. Here one feels so free that even poverty can be beautiful, colourful, joyful, and any strange behaviour is accepted.

Sonepat, 24 May 1972

I am at Sonepat with Shanti and a large group of his friends, in order to meet his teacher, Dr. Koshik. The doctor is a sweet man, full of love, with a blissful smile like the Buddha, wise and somewhat ironic. We are welcomed by his family with great simplicity and overwhelming hospitality. Like everywhere else in India I've always found that no matter how many guests there may be, they are treated with tremendous hospitality and offered somewhere to sit and an abundance of food.

For most of the time we sit with the doctor in a kind of meditation, talking from time to time, but very quietly and slowly. He expresses a keen interest in me, about my purpose for being in India so far from my home and has introduced me to his neighbours. When I sit with him, I feel immense peace and show him photographs of Babaji and tell him about the temple and my experiences there. I know from Shanti that he is a disciple of Krishnamurti and that he doesn't believe in the use of rituals, mantras and so on, only in self knowledge and self enquiry, but I feel a great respect from him. He talks about the importance of experiencing the spiritual in life and tells us that he attained a certain degree of awareness by simply sitting under a tree for some days, observing his own mind, seeking his own true self with eyes wide open, fully conscious.

After remaining with him for some time, I seem to have the same smile on my face that he has all of the time, a particularly quiet energy engulfing me; the doctor feeds us with Indian sweetmeats and showers us with love and affection.

Delhi, 26 May 1972

I've returned to Delhi again, before leaving for Rishikesh with Piero and Claudio to visit a great Tibetan lama. It feels right for me to know about other teachers and their diverse teachings, so as to deepen my understanding of Babaji and through this comparison come to value Him and His teachings even more.

Rishikesh, 27 May 1972

I have arrived in Rishikesh with Piero, Claudio and some other friends. On the train journey Rosa and I slept together on the same wooden bench.

Rishikesh is beautiful, green, and the water of the Ganges is clean, the river bordered by a wide beach of white sand. We are staying at the small ashram of Swami Prakash Bharti, surrounded by mango trees. The Indian people seem extremely pleased that we have come here and last night we cooked them a delicious feast of Italian rice with tomatoes.

The Swami has large, peaceful eyes, dark and warm. He plays a game with us: to each of us in turn he stares into our eyes to see who can look without blinking for the longest period of time, and he always wins. His eyes resemble the water of a tranquil lake.

The other day an extremely old sadhu arrived here, with exceptionally long hair knotted on his head, his body tall and thin, his skin brown. He walks particularly slowly on some strange wooden sandals and he seldom speaks. The Swami explained to us that he has been in a state of samadhi for one year, for all that time closed up in a cave, without consuming any food and even stopping his heart from beating and halting his breathing. Is that possible? Who knows if it's true, but the sadhu certainly seems like a being from another planet, he is extraordinarily gentle and detached from everything.

The other day Rosa was practising hatha yoga postures in the garden, completely naked. The Swami was embarrassed and laughed awkwardly, but the old sadhu continued watching her with complete indifference. The people here are extremely kind and they offer us food all the time as well as tea to drink, and they often smoke hashish. During the day we frequently take showers under the mango trees, trying to fend off the interminable heat and in the mornings we go to the river Ganges. The river is truly wonderful, the water pure and transparent, with a strong current.

The Swami is teaching me the Indian alphabet and some devotional songs. The other day he placed around my neck a rudraksha mala, a string of seeds from the tree dedicated to Lord Shiva. He told me that he is my guru but I don't feel this to be true. As yet I am not sure whether Babaji is my guru either, but I continually find myself thinking about Him and am surprised how difficult it is to take my eyes off the photograph of Him that I carry. There is a special beauty in His form, a purity that I have never encountered before, the energy of an angelic being.

In India, sadhus, the ascetics, are highly respected since they have dedicated their lives to God. People welcome them, give them food and hospitality. They often travel around the country having renounced a normal life, doing ascetic practices, like living on very little food or sleep, and meditating for long periods of time. Real sadhus are free spirits, beyond every rule and regulation, even if they follow their own spiritual discipline. They look, even physically, different from the rest of the Indian people, they have beautiful, supple bodies, often grow their hair very long and possess special eyes, warm and intense, with a particular light. They maintain a high degree of cleanliness, observing special rules of purity.

* * *

Tibetan Initiation - Lama Sakya Trinzin

Mussouri, 1 June 1972

Yesterday, with Piero and Claudio, I travelled from Rishikesh to Mussouri, high up in the mountains. We have come to live in a place called 'Happy Valley', a Tibetan village. Piero and Claudio want to take initiation from Sakya Trinzin, one of the four Dalai Lamas, head of the Sakya order, and they have brought me with them. They told me that this is a serious matter and that I should ask the Lama personally for permission to receive initiation. In the meantime we are staying together in a tiny room in a Tibetan house, sleeping on the floor on some straw mats.

There are only Tibetan people living in this area and I find them extraordinarily beautiful. I am attracted and fascinated by their lovely oriental faces, with high cheek-bones and almond shaped eyes that always express joy. The men often have very long plaited hair usually tied with a ribbon, they are incredibly kind-hearted and some of them even spend time knitting. Otherwise they continuously pray using long rosaries of wooden beads. Unlike the Indian people they don't have an excitable energy, neither do they make a lot of noise or invade the privacy of others. They are quiet, respectful, always smiling, and one feels safe with them. We use their small restaurants because the food is familiar to us Italians, light and without any spices, noodles and vegetable soup much like home, prepared with a mother's care. They also cook momo, a white, soft bread and continually drink salted tea with butter. The women are particularly elegant, clothed in long, traditional dresses, wearing ancient jewellery made of silver, coral and turquoise. On one occasion we went to eat in an elaborate, Western-style restaurant, but I prefer the small simple, Tibetan ones with the welcoming aroma of vegetables. Far away in the distance we can see the snowy peaks of the Himalayas, pure and majestic.

3 June 1972

Today we went to visit His Holiness Sakya Trinzin, in a Tibetan monastery, half-way towards Derhadun. We were permitted to talk with him alone for a few minutes, I felt very shy, particularly because I hardly speak any English. The impression he made on me was of a young man, rather fat and motherly, with a large, rotund face and long hair tied back at the neck, revealing large, turquoise earrings. He symbolizes the perfect integration of both male and female energy in a single human body and has green eyes, very clear, amiable and peaceful. I bowed to him and he placed his hand lightly on my head; small, graceful hands. He smiled softly, encouraging me to overcome my fear and said to me in Italian: 'Dio' - God, which made me feel safe and relaxed.

Then he told me about Mario, the first Italian who ventured up here a few years ago to be with the Tibetan masters. He asked if I wanted to follow the Dharma, the Buddhist path, and I answered that I probably felt more attracted by Hinduism. He nodded. Even so, I still asked him if it was possible for me to take the Buddhist initiation on the following day with Piero and Claudio and he replied that he would be pleased to give me permission. I felt extremely happy and came out from this encounter feeling uplifted, comforted.

Mussouri, 4 June 1972

Today we were initiated by a great Tibetan lama, Sakya Trinzin's teacher. Piero and Claudio have told me that it's a great honour and blessing. In fact I realize that many special things are happening to me, one after the other, as if this trip is invisibly guided.

The three of us were the only Westerners present for the initiation along with a large number of Tibetan monks, dressed in their yellow and dark red robes. The ceremony lasted for eight hours, all day long, and it became almost impossible for me to endure, patiently squatting on the floor cross-legged, experiencing great pain in my legs, not able to understand the language or the meaning of the different rituals. The sound of the tinkling bells and the smell of incense I found quite overwhelming. Tibetan people sing in a particularly unique way, a deep and reverberating tone, in perfect harmony.

The culminating moment of the initiation, when the lama placed a length of red-coloured string around each person's neck, as if sealing the ritual, made a lasting impression on me. He smiled at me, an ancient, wise smile, with a kind of complicity, as if he had known me forever. I came out of the room filled with a new power: something unusual had occurred, an indefinable effect difficult to describe. We have been instructed that we must now meditate and practice the teachings for fifteen days. During this period we can always go to see Lama Sakya Trinzin if necessary, talk with him and ask for further clarification. I feel honoured. From today the three of us are to be confined to our small rooms. The meditation is quite complicated: we should visualize a Buddha, adorned with certain symbols and each time recite a very long mantra with the help of a mala, a rosary.

6 June 1972

The main difficulty is to remain seated correctly and Claudio is teaching me how to sit with my back straight, crossing my legs in the proper way so that they don't feel paralysed. The Western body is used to sitting on chairs and sofas all the time, not seated on the floor, which strains all our muscles. The Indians however are incredibly supple, their joints flexible, both the men and the women quite used to living in close contact with the earth, squatting down, walking barefoot, eating with their hands, sleeping on the floor and cooking and cleaning by crouching down on the ground. The other big problem is to curb the activity of my mind and I try desperately to do that.

We visited the Lama for guidance and I asked him why the Buddha always sits on a lotus flower. He answered that the lotus is the symbol of our soul: as the beautiful lotus opens it's petals, resting on the stagnant, muddy water, so our soul can open to light and knowledge, opening beyond the darkness and ignorance.

Delhi, 20 June 1972

We are in Delhi again and have linked up with all our friends once more. It is strange how we keep meeting up with each other, as if an appointment is arranged through some telepathic message. Soon we will be returning to Mussouri for a further initiation, but I have begun to think about Babaji again. I remain in a dilemma about Him, because He doesn't speak, doesn't give any spoken teachings, doesn't teach meditation. He seems to do nothing and yet there is an inexplicable magic around Him. Every time I look at His photograph I perceive an intense light: maybe it's an hallucination - who knows?

22 June 1972

I have acquired a high fever and so I cannot leave with Piero and Claudio. At the last minute, before they departed, Claudio gave me a small image of Shiva, the deity of Yoga, maybe Babaji Himself. Perhaps I am being called: I begin to think of going to meet Him again in Vrindavan.