Полная версия

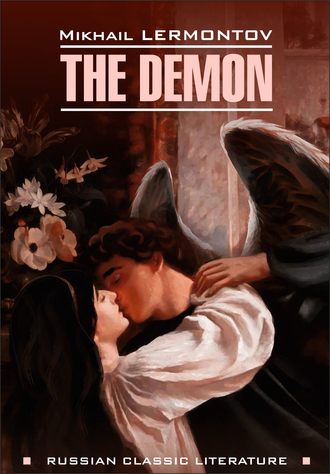

The Demon / Демон. Книга для чтения на английском языке

Mikhail Lermontov

The Demon

© КАРО, 2019

Все права защищены

M. Y. Lermontov

(1814–1841)

When we think of Lermontov, we see in our minds a huge mountain-peak somewhere in the heart of the Caucasus. Eternal silence reigns in its clefts and gorges. Its mass of ice and stone looks a picture of gloomy solitude. It seems to be indifferent to the turmoil of life. Still, there is boiling lava deep in its heart. Time and again it shakes from the fury of compressed inner forces. On its bare stony body little trees with lacy foliage climb higher and higher; and when the world is in bloom, winds laden with fragrance blow on its ragged brow, bringing the lure of distant lands.

Such is the poet Lermontov. This is, perhaps, why he loved the Caucasus all his life.

He is the most tragic of the Russian poets. From his very boyhood he was full of disdain for humanity, whose life he thought shallow, empty, and ugly; at the same time, he was irresistibly attracted by this very meaningless life. He cherished the ideal of a demon, a proud, lonely, and powerful superhuman creature challenging peaceful virtues and conventional happiness; at the same time he was fiercely craving for mortal love and sunlit human happiness, the absence of which filled his heart with pain. He had a cool and strong intellect, a power of analysis and criticism which revealed the futility of endeavor in this world and dictated an attitude of bored aloofness; at the same time he was torn by mad passions prompting him to the most unreasonable actions. He was inclined to protest, to repudiate, to curse, and almost without noticing he drifted into a prayer or saw the vision of an angel singing his quiet song over «a world of grief and tears». Altogether he is a profoundly unhappy nature, just the reverse of his older brother Pushkin.

If Pushkin is primarily the poet of the Russian soul and Russian nature, Lermontov is the first of the great Russian poets of the spirit. And if Pushkin is fundamentally national, acquiring international significance through his closeness to his native land, Lermontov is of universal value in himself as expressing those doubts and moods and gropings which are common to all cultured men. This did not prevent him from being a genuine Russian poet. One is even justified in looking for a connection between his dark rebellious moods and the dark conditions of the society in which he lived.

Lermontov is a self-centered poet. «The most characteristic feature of Lermontov's genius», Vladimir Solovyov says, «is a terrific intensity of thought concentrated on himself, on his ego, a terrific power of personal feeling». This, however, is no self-centeredness. Lermontov seeks refuge within himself because he finds no values in the ephemeral existence of the world. He sinks into brooding moods not because he finds in them satisfaction, but because life does not quell his thirst for harmony and truth. He is at war with society, with humanity, with the universe. He is at war even with God in the name of some great unearthly beauty which only at rare moments gives to his soul her luminous forebodings.

If Pushkin is the poet of all the people, Lermontov is the poet of the thinking elements in it. As such he played a colossal rôle in the spiritual history of his country. Generation after generation learned from him to hate the sluggishness of Russian life and the convention of every life, to repudiate compromises, to understand the longing of the soul for things non-existent, and to cherish freedom in the broad sense of the word.

Lermontov's form is in full accord with his moods, varying from the most exquisite tenderness to «verses coined of iron, dipped in poignancy and gall», from slow, thoughtful, and melancholy lines to volcanic outbursts of fury. In expressing delicate shades of emotions and in dignified refinement Lermontov is, perhaps, even superior to Pushkin. There is more of the elusive quality in his poems, that which cannot be expressed in definite words.

«Horrified by the triviality of life, by its corruption and helplessness, Lermontov sounded the motive of indignation. This indignation, so rare in Russia, utterly alien to Pushkin, timidly sounding in the work of Tchatzky[1], unknown to Gogol, was something new and unheard of. Through Lermontov's indignation, the Russian citizen for the first time became aware of himself as a real human being. The feeling of human dignity was stronger in Lermontov than all other feelings. It sometimes assumed unhealthy proportions, it led him to satanical pride, to contempt for all his surroundings. And in the name of this human dignity, unrecognized and downtrodden, he raised the voice of indignation».

«It appeared to him that not only society, those hangmen of freedom and genius, but also the Deity that gave him life, are making attempts on his inalienable rights as a man and are preventing him from living a full, eternal life which alone was of value to him. He saw no prospect of eternal life, no fullness of existence, no love without betrayal, no passion without satiety, and he did not wish to agree to less, as a deposed ruler does not wish to receive donations from the hand of the victor…»

«Lermontov is a religious nature, but his religion is primarily a groping, an indefinite, hazy admittance of life's tragic mystery».

Evg. Solovyov (Andreyevitch)«Lermontov introduced into literature the struggle against philistinism. Not, perhaps, till the end of the nineteenth century did philistinism meet a more ruthless, merciless foe. His aversion to philistinism is the key to his entire conception of life. His hatred for everything ordinary led him to his outspoken individualism and brought him near to that real romanticism which was unknown in Russia before him. It also imbued him with that contempt for the surrounding world which it is customary to view as Lermontov's characteristic pessimism. Lermontov, however, is not only a pessimist. Lermontov believed that life in itself could be beautiful, even at present. It could be beautiful, and it was all soiled under philistine rule, – this was for him the tragic contradiction. Hence his pessimism, his misanthropy, his hatred for life. He sees ethical philistinism in all social groups, in all society, in humanity at large. From this standpoint he is perhaps the most outspoken individualist in all Russian literature».

Ivanov-Razumnik«The leading motives of Lermontov's charming and sparkling poetry were a protest against the restrictions of individual freedom, a detached attitude towards an oppressing world, and the lure of another world which though not shaped clearly, not based on a definite foundation, is possessed of an irresistible power. This luring world is ordinarily somewhere in the past; it is a reminiscence, not a hope; at times it is heaven, at times, nature, at times, an idea, unclear yet so wonderful that the very sounds which give an inkling of its dark meaning cannot be listened to 'without emotion.' It is this better world which gives real meaning to a soul reminiscent of it, and the idea of this world lives in many of Lermontov's heroes.

The idea of something which does not allow us to accept our world as the best of all worlds, an idea appearing to men in the best moments of their life and stirring them to action and changes, was very strong in Lermontov's mind. The circumstances of his personal life and the conditions of his time might have strengthened his longing for another world; fundamentally, however, this longing is an inherent quality of mankind, and through it, Lermontov is close not only to his own contemporaries, but also to readers of the present and the future».

I. Ignatov«What an abundance of power, what a variety of ideas and images, emotions and pictures! What a strong fusion of energy and grace, depth and ease, elevation and simplicity!»

«Not a superfluous word; everything in its place; everything as required, because everything had been felt before it was said, everything had been seen before it was put on the canvas. His song is free, without strain. It flows forth, here as a roaring waterfall, there as a lucid stream».

«The quickness and variety of emotions are controlled by the unity of thought; agitation and struggle of opposing elements readily flow into one harmony, as the musical instruments in an orchestra join in one harmonious entity under the conductor's baton. And all sparkles with original colors, all is imbued with genuine creative thought and forms a new world similar to none».

V. G. ByelinsikyLyrical poems

(1828–1841)

«Invincible spiritual power; subdued complaints; the fragrant incense of prayer; flaming, stormy inspiration; silent sadness; gentle pensiveness; cries of proud suffering, moans of despair; mysterious tenderness of feeling; indomitable outbursts of daring desires; chaste purity; infirmities of modern society; pictures from the life of the universe; intoxicating lures of existence; pangs of conscience; sweet remorse; sobs of passion; quiet tears flowing in the fullness of a heart that has been tamed in the storms of life; joy of love; trembling of separation; gladness of meeting; emotions of a mother; contempt for the prose of life; mad thirst for ecstasies; completeness of spirit that rejoices over the luxuries of existence; burning faith; pains of soul's emptiness; outcry of a life that shuns itself; poison of negation; chill of doubt; struggle between fullness of experience and destructive reflection; angel fallen from heaven; proud demon and innocent child; impetuous bacchante and pure maiden, – all, all is contained in Lermontov's poetry: heaven and earth, paradise and hell».

V. G. ByelinskyThe Demon. A fantastic poem

(1829–1840)

The Demon, the Spirit of Evil, craves to free himself from his cold loneliness and to rise to heights of harmony through love for a mortal, the nun Tamar. The scene is set in the Caucasus, and the story is full of the mystic glow of the Orient.

The figure of the Demon was the creation Lermontov loved most. He worked on it practically all his life.

«Lermontov's Demon is not a symbol of the eternal Evil; he is not the Satan, he is a proud spirit, embittered and therefore sowing evil. He lived a lonely, monotonous life. He spread evil without satisfaction to himself. The Demon is an idealist suffering from disappointment. His hatred for mortals is too human. His love for Tamar suddenly transforms him. Her appearance makes him comprehend the sanctity of 'love, the good, and the beautiful' which had never been foreign to his soul, but lay hidden in its remotest corners. A Demon, however, is not destined for joy. Victory does not satisfy his heart, and torn by despair, he goes to tear the one he loves».

K. I. ArabazhinMtzyri[2]

(1840)

The poem of freedom. A Circassian boy brought up in a monastery and ready to become a monk, is lured by the wild freedom of nature. On a stormy night he runs away from his half-voluntary prison. For three days he is absent. On the fourth, he is found in the fields near the monastery. He is exhausted and dying. The poem consists mainly of the boy's story. He tells what he experienced in his dash for freedom.

In Mtzyri, Lermontov expressed one of his strongest emotions: his desire to be free like the wind, like the eagle on top of a mountain, like a powerful horse running through the boundless steppe. It is the fullness of life that lured both Lermontov and his Caucasian hero.

<…>

Much has been spoken about the influence of Byron on Lermontov's poetry. Lermontov himself was aware of a certain kinship of souls between himself and Byron. Careful investigators agree, however, that there was only a certain affinity of moods between both poets, but that Lermontov never imitated Byron.

Song of Tzar Ivan Vassilyevitch.[3] Epic poem

(1838)

Lermontov was a singer of heroism. Heroic moods and heroic deeds were at the very heart of his poetry. He found the heroic in his demon, in the wild inhabitants of the Caucasus, but he also looked for heroes in the past of Russia. The Song of Tzar Ivan Vassilyevitch presents a hero coming from the rank of the people and challenging the authority of the Tzar even under the threat of death. The poem is written in the tone and in the spirit of the heroic folk-tales and as such was considered a remarkable contribution to Russian literature.

Moissaye J. OlginThe Demon

An Eastern Legend

Part I

I

His way above the sinful earthThe melancholy Demon wingedAnd memories of happier daysAbout his exiled spirit thronged;Of days when in the halls of lightHe shone among the angels bright;When comets in their headlong flightWould joy to pay respect to himAs, chaste among the cherubim,Among th' eternal nebulaeWith eager mind and quick surmiseHe'd trace their caravanseraiThrough the far spaces of the skies;When he had known both faith and love,The happy firstling of creation!When neither doubt nor dark damnationHad whelmed him with the bitternessOf fruitless exile year by year,And when so much, so much… but thisWas more than memory could bear.II

Outcast long since, he wandered lone,Having no place to call his own,Through the dull desert of the worldWhile age on age about him swirled,Minute on minute – all the same.Prince of this world – which he held cheap —He scattered tares among the wheat…A joyless task without remission,Void of excitement, opposition —Evil itself to him seemed tame.III

And so – exiled from Paradise —He soared above the peaks of iceAnd saw the everlasting snowsOf Kazbek and the Caucasus,And, serpentine, the winding deepsOf that black, dragon-haunted passThe Daryal gorge; then the wild leapsOf Terek like a lion boundingWith mane of tangled spray that blowsBehind him, and a great roar soundingThrough all the hills, where beast and birdOn mountain scree and azure steepsThe river's mighty voice had heard;And, as he flew, the golden cloudsStreaked from the South in tattered shrouds…Companions on his Northbound course;And the great cliffs came crowding inAnd brooded darkly over himExuding some compelling forceOf somnolence above the stream…And on the cliff-tops castles rearedTheir towered heads and baleful staredOut through the mists – wardens who waitColossal at the mighty gateOf Caucasus – and all aboutGod's world lay wonderful and wild…But the proud Spirit looked with doubtAnd cool contempt on God's creation,His brow unruffled and sereneAdmitting no participation.IV

Before him now another sceneIn vivid beauty blooms.The patterned vales' luxuriant greenSpread like a carpet on the loomsOf Georgia, rich and blessed ground!These poplars like great pillars tower,And sounding streams trip over pebblesOf many colours in their courses.And, ember-bright, the rose trees flowerWhere nightingales forever warbleTo marble beauties fond discoursesForever deaf to their sweet sound.On sultry days the timid deerSeek out an ivy-curtained caveTo hide them from the midday heat;How bright, how live the leaves are here!A hundred voices soft conclaveA thousand flower-hearts that beat!The sensuous warmth of afternoon,The scented dew which falls to strewThe grateful foliage 'neath the moon,The stars that shine as full and brightAs Georgian beauties' eyes by night!..Yet in the outcast's barren breastAbundant nature woke no newUpsurge of forces long at rest,Touched off no other sentimentThan envy, hatred, cold contempt.V

Right high the house, right wide the courtGrey-haired Gudaal has builded him…In tears and labour dearly boughtBy slaves submissive to his whim.Across the neighbouring cliffs its shadeFrom sunrise dark and cool is laidA steep stair in the cliff-face hewnLeads from the corner-tower downTo the Aragva. Down this stairPrincess Tamara, young and fair,Goes gleaming, snow white veils a-flutter,To fetch her jars of river water.VI

In austere silence heretoforeThe house has looked across the valleys;But now wide open stands the doorGudaal holds feast to mark the marriageOf his Tamara: now the wineFlows freely and the zurna[4] skirts;The clan is gathered round to dineAnd on the roof-top, richly spreadWith orient rugs, the promised brideSits all amongst her laughing girls:In games and songs their time is spedAnd merriment. Beyond the hillsThe semicircle of the sunHas sunk already. Now the funCrows fast and furious. Now the steadyRhythmic clapping and the singingThe bride brings to her feet, poised ready,Her tambourine above her headIs circling, she herself goes wingingBird-light above rug, then stops,Looks round, and lets her lashes dropThat envious hide her shining glance;And now she raises raven brows,Now suddenly sways forward slightlyHer slender foot peeps out, and lightlyIt slides and swims into the dance;And see she smiles – a joyous gleamAglow with childish merriment.And yet… the white moon's sportive beamIn rippling water liquid bentWith such a smile could scarce compareMore live than life, than youth more fair.VII

So by the midnight star I swearBy blazing East and beaming WestNo Shah of Persia knew her peerNo King on earth was ever blessedTo kiss an eye so full and fine.The harem's sparkling fountain neverShowered such a form with dewy pearls!Nor had mortal fingers everCaressed a forehead so divineTo loose such splendid curls;Indeed, since Eve was first undoneAnd man from Eden forth must fareNo beauty such as this, I swear,Had bloomed beneath the Southern sun.VIII

So now for the last time she dancedAlas! Tomorrow, she, the heirOf old Gudaal, the daughter fairOf liberty must bow her headTo a slave's fate like one entranced,Adopt a country not her own,A family she'd never known—Often a secret doubt would shedA shadow on her radiant face;Yet all her movements were so freeAppealing, redolent of graceSo full of sweet simplicityThat, had the Demon soaring highAbove looked down and chanced to see…Then, mindful of his former race,He had turned from her – with a sigh…IX

The Demon did see… For one secondIt seemed to him that heaven beckonedTo make his arid soul resoundWith glorious, grace-bestowing sound —And once again his thought embracedThe sacrosanct significanceOf Goodness, Beauty and of Love!And, strangely moved, his memory tracedThe joys that he had known aboveA chain of long magnificenceBefore him link on link unfoldingAs though he watched the headlong flightOf star on star shoot through the night…And, long the touching scene beholding,Held spell-bound by some Power unseen,New sadness in his heart awoke.Then, suddenly, emotion spokeIn accents once familiar;Could this yet be regeneration?The subtle promptings of temptationHad gone as though they had not been…Oblivion? – God gave this not yet: —Nor would he, if he could, forget!..…X

Meanwhile, his gallant steed all latheredHastening to join his kin forgatheredTo celebrate his wedding dayThe bridegroom made his urgent way…Good fortune yet attended himTo bright Aragva's verdant bank.A line of camels after himSo weighted down with costly giftsThey scarce from hoof to hoof could shiftWound down the pathway, rank on rank,Now clear to view, now lost to sight,Bells chiming softly as they plod.Their master rode on in the vanTo guide his laden caravanThat followed where his horse had trod…Erect, the lithe waist girdled tight;Sabre and dagger-hilts shine brightBeneath the sun; and on his backA gleaming rifle, notched in black.The wind is fluttering the sleeveOf his chukhá[5] – all bravely braidedHis saddle-cloth of richest weave,The saddle with gay silks is broideredThe reigns are tasseled – and his steedIs of a priceless, golden breed.Nostrils dilated, twitching earsHe glances down and snorts his fearsOf the deep drop, the flying foamThat crests the rapids' leaping waves.How perilous the path they follow,The cliff o'erhangs the way so narrow,The deep ravine the torrent paves.The hour is late. – The sunset glowIs fading on the peaks of snow.The caravan makes haste for home.XI

But see – a chapel by the way…Here now has rested many a daySome prince, now canonized, but thenBy vengeful hand untimely slain. —And here the traveller must stayWhether he hastes to fight, or whetherTo join the feast, here he must everRein in his horse and humbly prayThe good saint to protect his lifeAgainst the lurking Moslem's knife.But now the bridegroom, overbold,Forgot his forefathers of oldAnd, by perfidious dreams misledOf how, beneath the cloak of night,He would embrace his bride, insteadOf holding by their pious riteHe yielded to the Demon's willSeduced by turbid thoughts – untilTwo figures – then a shot – aheadWhat was it? Rising in his stirrupsCramming his high hat on his browThe gallant lover, at the gallop,Plunged like a hawk upon his foe!No word he spoke, his whip cracked onceAnd once blazed forth his Turkish gun…Another shot. Wild cries. The PrinceGoes thundering on. The groans behindLong echoes in the valley find…Not long the fight. Of timorous mind,The Georgians turn and run!XII

Now all is silence; sadly huddledThe camels stand and stare befuddledUpon their erstwhile master – man,Lying dead amongst these silent fells.The only sound their harness bells,Ravaged and robbed their caravan;And see, the owl flies softly roundThe Christian bodies on the ground!No peaceful tomb beneath the stonesOf some old church will take these bonesLike those in which their fathers lie;Mothers nor sisters will not comeIn their long floating veils to cryOver these graves so far from home!Instead, by zealous hands, a crossWas raised to mark the dreadful lossJust where the road hugs close the sheerAnd towering cliff-wall, close to whereThey perished in the raid…And ivy, growing lush in spring,An emerald net about it flings…Here, weary of the toilsome road,The traveller yet lays down his loadTo rest in God's good shade…XIII

Swift as a stag still runs the horseSnorting as though he held his courseIn some fierce charge, now plunging onNow pulling up as though to harkenHis nostrils flared to sniff the wind:Then leaps up and comes ringing downOn all four hooves, sets sparkingThe stones and, in his mad career,His tangled mane streams out behind.A silent rider he does bearWho lurches forward now and thenTo rest his head in that wild mane.The reins lie slack in useless hands,The feet are deep-thrust in the stirrups,And on his saddle-cloth the bandsOf blood are broadening as they gallopAh gallant steed, your wounded masterYou bore from battle swift as lightThe ill-starred bullet sped yet fasterAnd overtook him in the night!XIV

Gudaal's is now a house of mourning,The people crowd into the court:Whose horse comes galloping in terrorTo fall before the rock-hewn gate?The lifeless rider, who is he?The battle fury on his faceHas left a deep inscribed traceOn coat and weapons they could seeFresh bloodstains, and a wiry strandOf mane was twisted in his hand,Not long you waited, youthful bride,And looked to see your bridegroom come:Alas, though he has gained your sideTo join the feasting at your homeHis princely word he keeps in vain…Never will he mount horse again.XV

Like thunder, the Lord's judgement brokeAbout this unsuspecting house!Tamara, sobbing on her couch,Gives free rein to the heavy tearsTill, shaken, she on them must choke…Then, suddenly, it seems she hearsAbove her words of wonder spoke:«Weep not, my child! Weep not in vain!Those tears are no life-giving rainTo call an unresponsive corpseBack to the living world again.They only serve to dull their sourceIn those clear eyes, those cheeks to burn…And he is far and will not learnOf all your bitter sorrow now;The winds of heaven now caressHis high, angelic brow;And heavenly music, heavenly light…What are the dreams and dark duress,The little hopes and stifled sighsOf earthly maidens in the sightOf one who dwells in paradise?Ah no, the lot of mortal man,Believe, my earthly angel dear,It merits not one second's spanYour precious sorrow here. On the wastes of airy ocean Rudderless and stripped of sail Through the mists in listless motion Stars in courses never fail; Through the boundless fields of heaven Traceless pass the fluffy sheep — Clouds dissolving in the even Reaches of the azure steppe. Hour of parting, hour of meeting, Brings them neither joy nor sorrow; Nor regrets for past fast fleeting; Nor desires for any morrow. Let remembrance day be only One long sorrow-laden day; For the rest, be strong and lonely Free of earthly cares as they!»«As soon as night has spread her veilTo cover the Caucasian heights;As soon as nature 'neath the spellOf magic words falls silent quite;As soon as on the cliffs the windRuns rustling through the fading grass,And the small bird that hides behindThe brittle blades flies up at last;And, drinking in the evening dewBeneath the vine-leaves in the gloom,Night flowering blossoms come to bloom;As soon as the great, golden moonAbove the mountain quietly peepsTo steal a stealthy glance at you;I shall come flying to watch your sleepAnd on your silken lashes layEnchanted dreams of golden day…»