Полная версия

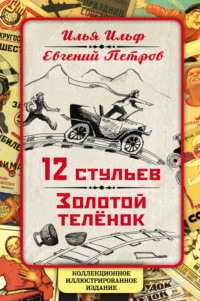

The Twelve Chairs / Двенадцать стульев. Книга для чтения на английском языке

The mechanic stopped talking in irritation. His black face glistened in the sun. The whites of his eyes were yellowish. Among the artisans owning cars in Stargorod, of whom there were many, Victor Polesov was the most gauche, and most frequently made an ass of himself. The reason for this was his over-ebullient nature. He was an ebullient idler. He was forever effervescing. In his own workshop in the second yard of no. 7 Pereleshinsky Street, he was never to be found. Extinguished portable furnaces stood deserted in the middle of his stone shed, the corners of which were cluttered up with punctured tyres, torn Triangle tyre covers, rusty padlocks (so enormous you could have locked town gates with them), fuel cans with the names «Indian» and «Wanderer», a sprung pram, a useless dynamo, rotted rawhide belts, oil-stained rope, worn emery paper, an Austrian bayonet, and a great deal of other broken, bent and dented junk. Clients could never find Victor Mikhailovich. He was always out somewhere giving orders. He had no time for work. It was impossible for him to stand by and watch a horse and cart drive into his or anyone else's yard. He immediately went out and, clasping his hands behind his back, watched the carter's actions with contempt. Finally he could bear it no longer.

«Where do you think you're going?» he used to shout in a horrified voice. «Move over!»

The startled carter would move the cart over.

«Where do you think you're moving to, wretch?» Victor Polesov cried, rushing up to the horse. «In the old days you would have got a slap for that, then you would have moved over».

Having given orders in this way for half an hour or so, Polesov would be just about to return to his workshop, where a broken bicycle pump awaited repair, when the peaceful life of the town would be disturbed by some other contretemps. Either two carts entangled their axles in the street and Victor Mikhailovich would show the best and quickest way to separate them, or workmen would be replacing a telegraph pole and Polesov would check that it was perpendicular with his own plumb-line brought specially from the workshop; or, finally, the fire-engine would go past and Polesov, excited by the noise of the siren and burned up with curiosity, would chase after it.

But from time to time Polesov was seized by a mood of practical activity. For several days he used to shut himself up in his workshop and toil in silence. Children ran freely about the yard and shouted what they liked, carters described circles in the yard, carts completely stopped entangling their axles and fire-engines and hearses sped to the fire unaccompanied-Victor Mikhailovich was working. One day, after a bout of this kind, he emerged from the workshop with a motor-cycle, pulling it like a ram by the horns; the motor-cycle was made up of parts of cars, fire-extinguishers, bicycles and typewriters. It had a one-and-a-half horsepower Wanderer engine and Davidson wheels, while the other essential parts had lost the name of the original maker. A piece of cardboard with the words «Trial Run» hung on a cord from the saddle. A crowd gathered. Without looking at anyone, Victor Mikhailovich gave the pedal a twist with his hand. There was no spark for at least ten minutes, but then came a metallic splutter and the contraption shuddered and enveloped itself in a cloud of filthy smoke. Polesov jumped into the saddle, and the motor-cycle, accelerating madly, carried him through the tunnel into the middle of the roadway and stopped dead. Polesov was about to get off and investigate the mysterious vehicle when it suddenly reversed and, whisking its creator through the same tunnel, stopped at its original point of departure in the yard, grunted peevishly, and blew up. Victor Mikhailovich escaped by a miracle and during the next bout of activity used the bits of the motor-cycle to make a stationary engine, very similar to a real one-except that it did not work.

The crowning glory of the mechanic-intellectual's academic activity was the epic of the gates of building no. 5, next door. The housing cooperative that owned the building signed a contract with Victor Polesov under which he undertook to repair the iron gates and paint them any colour he liked. For its part, the housing cooperative agreed to pay Victor Mikhailovich Polesov the sum of twenty-one roubles, seventy-five kopeks, subject to approval by a special committee. The official stamps were charged to the contractor.

Victor Mikhailovich carried off the gates like Samson. He set to work in his shop with enthusiasm. It took several days to un-rivet the gates. They were taken to pieces. Iron curlicues lay in the pram; iron bars and spikes were piled under the work-bench. It took another few days to inspect the damage. Then a great disaster occurred in the town. A water main burst on Drovyanaya Street, and Polesov spent the rest of the week at the scene of the misfortune, smiling ironically, shouting at the workmen, and every few minutes looking into the hole in the ground.

As soon as his organizational ardour had somewhat abated, Polesov returned to his gates, but it was too late. The children from the yard were already playing with the iron curlicues and spikes of the gates of no. 5. Seeing the wrathful mechanic, the children dropped their playthings and fled. Half the curlicues were missing and were never found. After that Polesov lost interest in the gates.

But then terrible things began to happen in no. 5, which was now wide open to all. The wet linen was stolen from the attics, and one evening someone even carried off a samovar that was singing in the yard. Polesov himself took part in the pursuit, but the thief ran at quite a pace, even though he was holding the steaming samovar in front of him, and looking over his shoulder, covered Victor Mikhailovich, who was in the lead, with foul abuse. The one who suffered most, however, was the yard-keeper from no. 5. He lost his nightly wage since there were now no gates, there was nothing to open, and residents returning from a spree had no one to give a tip to. At first the yard-keeper kept coming to ask if the gates would soon be finished; then he tried praying, and finally resorted to vague threats. The housing cooperative sent Polesov written reminders, and there was talk of taking the matter to court. The situation had grown more and more tense.

Standing by the well, the fortune-teller and the mechanic-enthusiast continued their conversation.

«Given the absence of seasoned sleepers», cried Victor Mikhailovich for the whole yard to hear, «it won't be a tramway, but sheer misery!»

«When will all this end!» said Elena Stanislavovna. «We live like savages!»

«There's no end to it…. Yes. Do you know who I saw today? Vorobyaninov».

In her amazement Elena Stanislavovna leaned against the wall, continuing to hold the full pail of water in mid-air.

«I had gone to the communal-services building to extend my contract for the hire of the workshop and was going down the corridor when suddenly two people came towards me. One of them seemed familiar; he looked like Vorobyaninov. Then they asked me what the building had been in the old days. I told them it used to be a girls' secondary school, and later became the housing division. I asked them why they wanted to know, but they just said, Thanks' and went off. Then I saw clearly that it really was Vorobyaninov, only without his moustache. The other one with him was a fine-looking fellow. Obviously a former officer. And then I thought…»

At that moment Victor Mikhailovich noticed something unpleasant. Breaking off what he was saying, he grabbed his can and promptly hid behind the dustbin. Into the yard sauntered the yard-keeper from no. 5. He stopped by the well and began looking round at the buildings. Not seeing Polesov anywhere, he asked sadly:

«Isn't Vick the mechanic here yet?»

«I really don't know», said the fortune-teller. «I don't know at all». And with unusual nervousness she hurried off to her apartment, spilling water from the pail.

The yard-keeper stroked the cement block at the top of the well and went over to the workshop. Two paces beyond the sign:

ENTRANCE TO METAL WORKSHOP

was another sign:

METAL WORKSHOP

AND PRIMUS STOVE REPAIRS

under which there hung a heavy padlock. The yard-keeper kicked the padlock and said with loathing:

«Ugh, that stinker!»

He stood by the workshop for another two or three minutes working up the most venomous feelings, then wrenched off the sign with a crash, took it to the well in the middle of the yard, and standing on it with both feet, began creating an unholy row.

«You have thieves in no. 7!» howled the yard-keeper. «Riffraff of all kinds! That seven-sired viper! Secondary education indeed! I don't give a damn for his secondary education! Damn stinkard!»

During this, the seven-sired viper with secondary education was sitting behind the dustbin and feeling depressed. Window-frames flew open with a bang, and amused tenants poked out their heads.

People strolled into the yard from outside in curiosity. At the sight of an audience, the yard-keeper became even more heated.

«Fitter-mechanic!» he cried. «Damn aristocrat!»

The yard-keeper's parliamentary expressions were richly interspersed with swear words, to which he gave preference. The members of the fair sex crowding around the windows were very annoyed at the yard-keeper, but stayed where they were.

«I'll push his face in!» he raged. «Education indeed!»

While the scene was at its height, a militiaman appeared and quietly began hauling the fellow off to the police station. He was assisted by Some young toughs from Fastpack. The yard-keeper put his arms around the militiaman's neck and burst into tears. The danger was over.

A weary Victor Mikhailovich jumped out from behind the dustbin. There was a stir among the audience.

«Bum!» cried Polesov in the wake of the procession. «I'll show you! You louse!»

But the yard-keeper was weeping bitterly and could not hear. He was carried to the police station, and the sign «Metal Workshop and Primus Stove Repairs» was also taken along as factual evidence. Victor Mikhailovich bristled with fury for some time.

«Sons of bitches!» he said, turning to the spectators. «Conceited bums!»

«That's enough, Victor Mikhailovich», called Elena Stanislavovna from the window. «Come in here a moment».

She placed a dish of stewed fruit in front of Polesov and, pacing up and down the room, began asking him questions.

«But I tell you it was him-without his moustache, but definitely him», said Polesov, shouting as usual. «I know him well. It was the spitting image of Vorobyaninov».

«Not so loud, for heaven's sake! Why do you think he's here?»

An ironic smile appeared on Polesov's face.

«Well, what do you think?»

He chuckled with even greater irony.

«At any rate, not to sign a treaty with the Bolsheviks».

«Do you think he's in danger?»

The reserves of irony amassed by Polesov over the ten years since the revolution were inexhaustible. A series of smiles of varying force and scepticism lit up his face.

«Who isn't in danger in Soviet Russia, especially a man in Vorobyaninov's position. Moustaches, Elena Stanislavovna, are not shaved off for nothing».

«Has he been sent from abroad?» asked Elena Stanislavovna, almost choking.

«Definitely», replied the brilliant mechanic.

«What is his purpose here?»

«Don't be childish!»

«I must see him all the same».

«Do you know what you're risking?»

«I don't care. After ten years of separation I cannot do otherwise than see Ippolit Matveyevich».

And it actually seemed to her that fate had parted them while they were still in love with one another.

«I beg you to find him. Find out where he is. You go everywhere; it won't be difficult for you. Tell him I want to see him. Do you hear?»

The parrot in the red underpants, which had been dozing on its perch, was startled by the noisy conversation; it turned upside down and froze in that position.

«Elena Stanislavovna», said the mechanic, half-rising and pressing his hands to his chest, «I will contact him».

«Would you like some more stewed fruit?» asked the fortune-teller, deeply touched.

Victor Mikhailovich consumed the stewed fruit irritably, gave Elena Stanislavovna a lecture on the faulty construction of the parrot's cage, and then left with instructions to keep everything strictly secret.

Chapter Eleven. The Mirror-of-Life Index

The next day the partners saw that it was no longer convenient to live in the caretaker's room. Tikhon kept muttering away to himself and had become completely stupid, having seen his master first with a black moustache, then with a green one, and finally with no moustache at all. There was nothing to sleep on. The room stank of rotting manure, brought in on Tikhon's new felt boots. His old ones stood in the corner and did not help to purify the air, either.

«I declare the old boys' reunion over», said Ostap. «We must move to a hotel».

Ippolit Matveyevich trembled. «I can't».

«Why not?»

«I shall have to register».

«Aren't your papers in order?»

«My papers are in order, but my name is well known in the town. Rumours will spread».

The concessionaires reflected for, a while in silence.

«How do you like the name Michelson?» suddenly asked the splendid Ostap.

«Which Michelson? The Senator?»

«No. The member of the shop assistants' trade union».

«I don't get you».

«That's because you lack technical experience. Don't be naive!»

Bender took a union card out of his green jacket and handed it to Ippolit Matveyevich.

«Konrad Karlovich Michelson, aged forty-eight, non-party member, bachelor; union member since 1921 and a person of excellent character; a good friend of mine and seems to be a friend of children… But you needn't be friendly to children. The militia doesn't require that of you».

Ippolit Matveyevich turned red. «But is it right?»

«„Compared with our“ concession, this misdeed, though it does come under the penal code, is as innocent as a children's game».

Vorobyaninov nevertheless balked at the idea.

«You're an idealist, Konrad Karlovich. You're lucky, otherwise you might have to become a Papa Christosopulo or Zlovunov».

There followed immediate consent, and without saying goodbye to Tikhon, the concessionaires went out into the street.

They stopped at the Sorbonne Furnished Rooms. Ostap threw the whole of the small hotel staff into confusion. First he looked at the seven-rouble rooms, but disliked the furnishings. The cleanliness of the five-rouble rooms pleased him more, but the carpets were shabby and there was an objectionable smell. In the three-rouble rooms everything was satisfactory except for the pictures.

«I can't live in a room with landscapes», said Ostap.

They had to take a room for one rouble, eighty. It had no landscapes, no carpets, and the furniture was very conservative – two beds and a night table.

«Stone-age style», observed Ostap with approval. «I hope there aren't any prehistoric monsters in the mattresses».

«Depends on the season», replied the cunning room-cleaner. «If there's a provincial convention of some kind, then of course there aren't any, because we have many visitors and we clean the place thoroughly before they arrive. But at other times you may find some. They come across from the Livadia Rooms next door».

That day the concessionaires visited the Stargorod communal services, where they obtained the information they required. It turned out that the housing division had been disbanded in 1921 and that its voluminous records had been merged with those of the communal services.

The smooth operator got down to business. By evening the partners had found out the address of the head of the records department, Bartholomew Korobeinikov, a former clerk in the Tsarist town administration and now an office-employment official.

Ostap attired himself in his worsted waistcoat, dusted his jacket against the back of a chair, demanded a rouble, twenty kopeks from Ippolit Matveyevich, and set off to visit the record-keeper. Ippolit Matveyevich remained at the Sorbonne Hotel and paced up and down the narrow gap between the two beds in agitation. The fate of the whole enterprise was in the balance that cold, green evening. If they could get hold of copies of the orders for the distribution of the furniture requisitioned from Vorobyaninov's house, half the battle had been won. There would still be tremendous difficulties facing them, but at least they would be on the right track.

«If only we can get the orders», whispered Ippolit Matveyevich to himself, lying on the bed, «if only we can get them».

The springs of the battered mattress nipped him like fleas, but he did not feel them. He still only had a vague idea of what would follow once the orders had been obtained, but felt sure everything would then go swimmingly.

Engrossed in his rosy dream, Ippolit Matveyevich tossed about on the bed. The springs bleated underneath him.

Ostap had to go right across town. Korobeinikov lived in Gusishe, on the outskirts.

It was an area populated largely by railway workers. From time to time a snuffling locomotive would back its way along the walled-off embankment, above the houses. For a second the rooftops were lit by the blaze from the firebox. Now and then empty goods trains went by, and from time to time detonators could be heard exploding. Amid the huts and temporary wooden barracks stretched the long brick walls of still damp blocks of flats.

Ostap passed an island of lights-the railway workers' club-checked the address from a piece of paper, and halted in front of the record-keeper's house. He rang a bell marked «Please Ring» in embossed letters.

After prolonged questioning as to «Who do you want?» and «What is it about?» the door was opened, and he found himself in a dark, cupboard-cluttered hallway. Someone breathed on him in the darkness, but did not speak.

«Is Citizen Korobeinikov here?» asked Ostap.

The person who had been breathing took Ostap by the arm and led him into a dining-room lit by a hanging kerosene lamp. Ostap saw in front of him a prissy little old man with an unusually flexible spine. There was no doubt that this was Citizen Korobeinikov himself. Without waiting for an invitation, Ostap moved up a chair and sat down.

The old man looked fearlessly at the high-handed stranger and remained silent. Ostap amiably began the conversation.

«I've come on business. You work at the communal-services records office, don't you?»

The old man's back started moving and arched affirmatively.

«And you worked before that in the housing division?»

«I have worked everywhere», he answered gaily.

«Even in the Tsarist town administration?»

Here Ostap smiled graciously. The old man's back contorted for some time and finally ended up in a position implying that his employment in the Tsarist town administration was something long passed and that it was not possible to remember everything for sure.'

«And may I ask what I can do for you?» said the host, regarding his visitor with interest.

«You may», answered the visitor. «I am Vorobyaninov's son».

«Whose? The marshal's?»

«Yes».

«Is he still alive?»

«He's dead, Citizen Korobeinikov. He's gone to his rest».

«Yes», said the old man without any particular grief, «a sad event. But I didn't think he had any children».

«He didn't», said Ostap amiably in confirmation.

«What do you mean?»

«I'm from a morganatic marriage».

«Not by any chance Elena Stanislavovna's son?»

«Right!»

«How is she?»

«Mum's been in her grave some time».

«I see. I see. How sad».

And the old man gazed at Ostap with tears of sympathy in his eyes, although that very day he had seen Elena Stanislavovna at the meat stalls in the market.

«We all pass away», he said, «but please tell me on what business you're here, my dear … I don't know your name».

«Voldemar», promptly replied Ostap.

«Vladimir Ippolitovich, very good».

The old man sat down at the table covered with patterned oilcloth and peered into Ostap's eyes.

In carefully chosen words, Ostap expressed his grief at the loss of his parents. He much regretted that he had invaded the privacy of the respected record-keeper so late at night and disturbed him by the visit, but hoped that the respected record-keeper would forgive him when he knew what had brought him.

«I would like to have some of my dad's furniture», concluded Ostap with inexpressible filial love, «as a keepsake. Can you tell me who was given the furniture from dad's house?»

«That's difficult», said the old man after a moment's thought. «Only a well-to-do person could manage that. What's your profession, may I ask?»

«I have my own refrigeration plant in Samara, run on artel lines».

The old man looked dubiously at young Vorobyaninov's green suit, but made no comment.

«A smart young man», he thought.

«A typical old bastard», decided Ostap, who had by then completed his observation of Korobeinikov.

«So there you are», said Ostap.

«So there you are», said the record-keeper. «It's difficult, but possible».

«And it involves expense», suggested the refrigeration-plant owner helpfully.

«A small sum…»

«„Is nearer one's heart“, as Maupassant used to say. The information will be paid for».

«All right then, seventy roubles».

«Why so much? Are oats expensive nowadays?»

The old man quivered slightly, wriggling his spine.

«Joke if you will…»

«I accept, dad. Cash on delivery. When shall I come?»

«Have you the money on you?»

Ostap eagerly slapped his pocket.

«Then now, if you like», said Korobeinikov triumphantly.

He lit a candle and led Ostap into the next room. Besides a bed, obviously slept in by the owner of the house himself, the room contained a desk piled with account books and a wide office cupboard with open shelves. The printed letters A, B, C down to the rearguard letter Z were glued to the edges of the shelves. Bundles of orders bound with new string lay on the shelves.

«Oho!» exclaimed the delighted Ostap. «A full set of records at home».

«A complete set», said the record-keeper modestly. «Just in case, you know. The communal services don't need them and they might be useful to me in my old age. We're living on top of a volcano, you know. Anything can happen. Then people will rush off to find their furniture, and where will it be? It will be here. This is where it will be. In the cupboard. And who will have preserved it? Who will have looked after it? Korobeinikov! So the gentlemen will say thank you to the old man and help him in his old age. And I don't need very much; ten roubles an order will do me. Otherwise, they might as well look for the wind in the field. They won't find the furniture without me».

Ostap looked at the old man in rapture.

«A marvellous office», he said. «Complete mechanization. You're an absolute hero of labour!»

The flattered record-keeper began explaining the details of his pastime. He opened the thick registers.

«It's all here», he said, «the whole of Stargorod. All the furniture. Who it was taken from and who it was given to. And here's the alphabetical index-the mirror of life! Whose furniture do you want to know about? Angelov, first-guild merchant? Certainly. Look under A. A, Ak, Am, Am, Angelov. The number? Here it is-82742. Now give me the stock book. Page 142. Where's Angelov? Here he is. Taken from Angelov on December 18, 1918: Baecker grand piano, one, no. 97012; piano stools, one, soft; bureaux, two; wardrobes, four (two mahogany); bookcases, one … and so on. And who was it all given to? Let's look at the distribution register. The same number. Issued to. The bookcase to the town military committee, three wardrobes to the Skylark boarding school, another wardrobe for the personal use of the Stargorod province food office. And where did the piano go? The piano went to the old-age pensioners' home, and it's there to this day».

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.