Полная версия

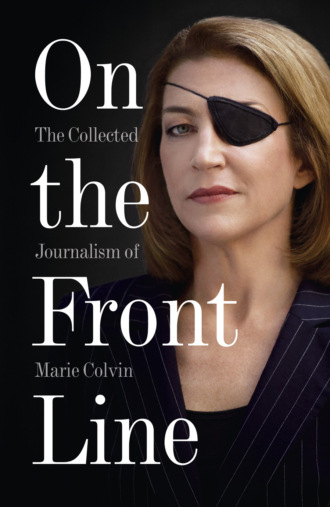

On the Front Line: The Collected Journalism of Marie Colvin

Baghdad’s survival and the news that Saddam had launched Scud rockets at Israel had many Palestinians and their Iraqi supporters still believing that he would achieve his goal of somehow freeing Palestinian land from Israel.

As the sun set on Friday, I watched two orbs of light streak low across the city skyline, just missing the rooftops, and smash into the Dora oil refinery. A huge ball of fire erupted and smoke drifted back over Baghdad.

Bombing continued sporadically that night and at dawn the refinery had only three instead of four chimneys. The 20-storey communications tower which had lost its top three storeys to an unseen missile on Friday, as if to an invisible hand, had completely disappeared from the skyline by Saturday morning.

On Saturday afternoon, I was gazing idly from a fifth-floor window across the Zawra zoo park opposite the hotel when I suddenly realised that a cruise missile was heading above the trees straight for us. It seemed to be white. I could see its little fins. There was no smoke trail coming from it.

I thought it was going to hit the hotel, and I yelled out. But it turned right and skirted the building, as if following a street map, and hit the old parliament building about half a mile away, sending up a white pall of smoke.

Another cruise landed even closer, disappearing with a deafening crash into breeze-block staff quarters next to the hotel. The huts burst into flames and shrapnel showered the lawn and swimming pool. Glass from broken windows littered the hotel lobby as hotel workers dragged an electronic circuit board into the air-raid shelter, dancing around it, ululating and shouting that they had downed an American plane.

It was a relentless afternoon attack. At least two more missiles hit the Dora refinery again, sparking a fire that lit Baghdad with a beautiful rose glow late into the night.

Conditions at the Rashid hotel were becoming primitive. Electricity remained off and journalists worked at night by candlelight. Sanitation had broken down, toilets could not flush, and we had been washing in the swimming pool.

The officials minding us had had enough. They had stayed in the shelter for days and had not seen their families nor been able to contact them by telephone. They were worried about our safety and about the detail of what we were reporting. We were ordered to leave.

On Saturday night, as I packed and sat up late with other journalists discussing our departure, a Palestinian friend stopped by to say farewell. An articulate, educated man, he was trying to explain why so much of the Arab world had come out in support of Saddam despite his invasion of Kuwait and oppressive policies at home.

‘You must understand that if Saddam goes, no Westerner will be safe walking down an Arab street. I will pick up a machinegun and fight the Americans. A year ago I would have told you I hated Saddam and his regime. But he has become a symbol for us. Saddam is the result of the humiliation of the war of 1967 and of all the humiliations we have suffered from the West. If we let you destroy Saddam now, you will destroy all of us Arabs again.’ He added: ‘It is a question of dignity. Saddam came along with his rockets and stood up to you and we said, “Why not?”’

I rose at 5am to the incongruous sounds of a cock crowing and another barrage of anti-aircraft fire, this time a light and sparkling scattering of shots of tracer into the air. The government newspaper headline read: ‘Hussein rockets answer the call of Palestine. The road to Jerusalem is open.’ Uniting under attack behind Saddam, people might even believe this hyperbole.

Downstairs the taxi drivers demanded the exorbitant sum of $3,000 a car to the Jordanian border, because a convoy of cars that had left on Saturday had been bombed near the town of Rutba in the western desert.

We drove out of Baghdad on the deserted highway, past military camps on the city’s perimeter that appeared surprisingly intact, with anti-aircraft guns still manned on mounds along their boundaries. Government army lorries trundled south towing anti-aircraft guns, but there was little other traffic. The journey through flat, unbroken rocky desert was uneventful. Iraqi guards stamped exit visas into our passports at the desolate border station of Trebeil. Among the shabby breeze-block buildings we left behind the stacks of abandoned cheap luggage from earlier refugees and drove across the no man’s land into Jordan.

Ghosts of war stalk Basra’s empty streets

SOUTHERN IRAQ

23 August 1992

The fat singer in the smoky gloom of the Eastern Nights Club in Basra was just getting into her stride when the lights went up. The laughter at a table of rich merchants died instantly.

An unsmiling officer in khaki swept through the beads hanging across the door followed by eight soldiers, who fanned out between tables draped in red velvet and dotted with bottles of Scotch. The customers froze. They knew that last month Saddam Hussein executed 42 merchants for profiteering.

The officer scanned the room, but he had no interest in the traders or the soldier sitting with a buxom prostitute. His eyes fell on a table of eight young men.

Two soldiers moved forward, ordering the men to their feet with the flick of a Kalashnikov. The officer pulled out battered papers. The first passed and was motioned to sit; the second was led away.

‘Oh, he didn’t even have time to change his clothes,’ lamented Ishar, a young prostitute. A second glance told the story: the arrested man still wore his olive army trousers under a white shirt and maroon jacket. He was a deserter. Four more of his companions were led away.

As the soldiers left, there was a moment of silence. Then the manager strode to the dance floor and, with a grandiose flourish, restarted the band and the singer. The lights dimmed and laughter flooded the room again – the forced laughter of relief.

Basra, capital of the south and home to Iraq’s Shi’ite majority, is a city under siege. Whereas Baghdad has been largely rebuilt since the Gulf War, Basra still bears the scars of allied bombing and the rebellion that saw officials of the ruling Ba’ath party slaughtered in the streets and government buildings and hospitals looted and torched.

Today, fear of Iranian infiltrators, army deserters and fugitive rebels empties the city’s streets after 9pm. Food is scarce and expensive. The factories, port and oil plants are closed; its hospitals desperately short of medicine and filled with malnourished babies.

Fifty life-sized statues of dead heroes of the Iran–Iraq war line the corniche on the Shatt al-Arab, their arms pointing across the water towards the old Iranian foe. Locals, fearful of the enemy within, joke that they should point in every direction.

The man charged with keeping order in Basra is Brigadier General Latif Omoud, a governor who sits behind a desk with 10 telephones. It is impressive, but unconvincing.

The city’s telecommunications have not been restored since the end of the Gulf War 18 months ago, and a line has to be installed to each number he wants to call. ‘The pink telephone is for my girlfriend,’ he joked.

Dressed in a neatly pressed uniform and with his hands manicured, Omoud appears unbowed by the calamitous state of the city he took over after Iraqi forces crushed the Shi’ite rebellion in March last year.

He has not been amused, however, by the news that Britain, France and the United States were preparing to enforce an air exclusion zone south of the 32nd parallel to protect the Shi’ites in the southern marshlands from destruction by Saddam.

Any Iraqi plane or helicopter that flies will risk being shot down. Since Basra is 100 miles south of the 32nd parallel, Omoud was angry and perplexed. The general, who sees himself on the front line with Iran, claims to have quelled the ‘security problem’ in Basra.

But the road south from al-Amarah to Basra remains a no-go zone at night; checkpoints are attacked, soldiers killed and civilians robbed. It will get much worse, said Omoud, if the allied plan is enforced.

‘We have arrested many infiltrators in Basra,’ he said. ‘They come from Iran to commit acts of sabotage. We should be allowed to fly our planes and helicopters to counter the Iranian menace.’

He made no apology for the attacks on the marshes, insisting they were a haven for rebels and Iranian agents. The West, Omoud said, was short-sighted: ‘The Iranians are still interested in exporting their revolution.’

Then the governor was off, speeding away in his armoured white Mercedes followed by a jeep with a mounted machinegun and two cars full of soldiers. Behind him, sweltering in the 53°C heat, bricklayers continued rebuilding his governor’s garrison, which had been gutted during the rebellion.

The real picture in the south is difficult to piece together in a tightly controlled nation of nervous people. But it is clear that the government has won the upper hand in the war with the 30,000 rebels in the Hawaiza marshes, a 6,000-square-mile swampland of waterways and reed banks.

The attacks against insurgents in the marshes, according to diplomats in Baghdad and interviews in Basra and al-Amarah, began around 21 July. There is little doubt they were brutal. Diplomats believe that Iraq used helicopter gunships and artillery against the marsh Arabs but has not sent in ground troops because of the treacherous terrain.

The rebels had little chance. Besieged, they were killed or forced to flee or surrender. Many civilian marsh dwellers also died. The season favoured the army; in July and August the marshes dry up, making operations easier. One source said 9,000 rebels had surrendered or been captured.

The few townspeople in al-Amarah willing to talk say the roads are too dangerous to travel at night. At the Saddam Hussein general hospital, Dr Ayad Abdul Aziz said there had been constant attacks on civilians and soldiers in the area near the marshes.

But operations by the Iraqi army seem to have ended. The military appears to be in defensive positions. Nightly on Iraqi national television, captured rebels make their confessions.

One Iraqi, a PoW from the Iraq–Iran war, claimed he had been forced to fight for Iran: ‘It was decided to start a sabotage campaign. I received verbal instructions to go on a fact-finding mission in Iraq. We needed information on the security status. I carried false identification, money and a pistol.’

He said he met rebels who had plentiful supplies of explosives and weapons, and sent back information to Iran. The interviewees show extraordinary calm while making their confessions; it is widely assumed they are executed afterwards.

‘Of course they are calm,’ said one Iraqi viewer last week. ‘They know it is the end of their lives.’

Critics are silenced as Saddam rebuilds Iraq

BAGHDAD

4 October 1992

Arc lights on the roof of the National Conference Palace shone through the night and into the pink dawn last week as construction workers hammered and welded round the clock to repair the bombed building. It might have been an unremarkable scene in a city recovering from 43 consecutive days of air attack, except for one thing: it was the last important building to be restored.

Little more than 18 months after the Gulf War ceasefire, you have to scour the back streets of Baghdad for any sign of the heavy bombing it underwent. Iraqi engineers have repaired all but one of the bridges destroyed during the hostilities and rebuilt the 14-storey central telephone exchange on the bank of the Tigris, bombed so often that by the end of the conflict it was just a concrete shell with steel and wires curling from the windows. Gutted ministries have been reconstructed, rubble removed.

The main power plant, which was lit almost nightly by flashes from explosions, is working at 90% of its pre-war capacity. Soon after the bombing ended, an engineer at the plant said it would take at least two years to get it working again; but there was not one blackout during the blazing hot summer, when Baghdadis ran their air-conditioning at full blast.

The list of achievements goes on. Oil production is back to about 800,000 barrels a day, although United Nations sanctions prohibit Iraq from selling its petroleum abroad. Restored refineries supply more than enough petrol and heating oil for Iraq’s domestic needs and exports to Jordan. Iraqi experts say they could now pump 2 million barrels a day.

The six-lane highway from Baghdad to the Jordanian border, littered with craters from nightly raids, is now a smoothly surfaced superhighway. Three weeks ago the evening news showed Saddam Hussein congratulating workers for finishing repairs on the presidential palace.

In fact, much of the current construction in Baghdad is of new buildings. Enormous villas are sprouting in the wealthy Mansour district, financed by war profits. Newspapers report the progress of the Third River project, the construction of a 350-mile canal that will drain the rising water in the Tigris-Euphrates basin to reclaim land.

Yesterday, Saddam announced that construction would resume, using Iraqi designs and expertise, of an enormous petrochemical complex which the war forced foreign companies to abandon. When finished, it will be the largest in the Middle East.

What happened? Just 18 months ago, Saddam sat in a windowless bunker, wrapped in a heavy woollen greatcoat because there was no heat and in dim light because even the president had to rely on a diesel-fuelled generator for electricity. Outside, his country lay in ruins. The electricity grid was destroyed. Sewerage and water systems, telephones, even traffic lights did not work. His oil refineries were reduced to tangled machinery and holed tanks. He had just been kicked out of Kuwait, his army was in disarray, a rebellion raged in 14 of his 18 provinces, and much of his air force was parked on the territory of his enemy, Iran.

Since then, Iraq has been rebuilt without money from oil exports, without the teams of foreign experts that once staffed the military and civilian industries, without the $4 billion of assets frozen in overseas banks, and under strict sanctions that ban the import of spare parts or construction materials.

The key to the revival is Saddam. According to those around him, he did not even falter in the face of devastation so massive that allied leaders believed his downfall to be inevitable. Saddam never, ever, gives up, they say. This mentality was a liability during the Gulf crisis, when he refused to leave Kuwait, but it was crucial to the rebuilding of Iraq. He went from the Mother of all Battles to the Mother of all Reconstructions without missing a beat.

Saddam emerged unrepentant from his bunker and ready to rebuild. The 53-year-old president knows his people well. He needed to remove the daily reminders of the war, and his responsibility for it. ‘I don’t want to see any war damage in the capital,’ an Iraqi official quoted him as saying. In a dictatorship as absolute as Iraq, such an order concentrates the mind. Construction crews began working 24 hours a day, even on Saturday, the Muslim Sabbath.

Saddam was fortunate in the resources he commanded. When UN sanctions were imposed in August 1990, Iraq had two years’ supply of spare parts in storage. There were millions of dollars in overseas slush funds, which his brother, Barzan al-Tikriti, Iraqi representative to the UN in Geneva, used to buy spare parts that were smuggled in through Jordan. Perhaps most important, Iraq is home to the best educated and disciplined people in the Arab world. He had no need for foreign technical expertise.

Saddam identified himself with the reconstruction effort. News programmes regularly broadcast East-European-style footage of him inspecting repaired factories.

A special Order of the President was created to reward those who excelled in the rebuilding effort, and the annual conference of the ruling Ba’ath party was named the Jihad (Holy War) of Reconstruction Congress.

Nothing proved too insignificant for Saddam’s attention. During a nationally televised meeting, he advised education officials to ‘give special attention to sanitary facilities for students. The student who cannot go to the bathroom all day because it is dirty cannot concentrate.’

There has been no let-up in the momentum. Saddam warned his ministers last month: ‘From now on, those government officials who fail in their responsibilities will be considered as being involved in economic sabotage. Stringent measures will be taken against them, similar to the strict measures taken against the traitors who were involved in profiteering and monopoly.’ It was an undisguised reference to the 42 merchants executed in July for profiteering.

The success of the reconstruction has won Saddam the admiration of his greatest critics. Ordinary Iraqis, who love their bridges and modern buildings the way Europeans love their nation’s art treasures or scenic vistas, are proud that Iraq has rebuilt its infrastructure quickly, and without outside help.

The country still has serious problems, though. Inflation has wrecked the economy, with prices spiralling higher almost daily – last week rice sold for 8½ dinars ($25) a kilo, a spare tyre for 2,000 dinars. The country’s future wealth is mortgaged to old debts and war reparation. On Friday, the UN security council voted to seize $1 billion of Iraq’s frozen assets to pay for UN operations.

But the dissatisfaction of Iraqis with their financial lot is irrelevant. Along with his bridges, Saddam has reconstructed his formidable security apparatus. The army has been restored to 40% of its pre-war capacity, with about 400,000 troops under arms; the ubiquitous Mukhabarat security men are back on the streets. The south is under undeclared martial law; generals have replaced civilians as governors in every southern province.

Saddam’s success has also undermined Washington’s attempts to persuade Iraqis to oppose the regime. I heard again and again in Baghdad, albeit in hushed tones, that Saddam and Bush had a secret deal: why else would the allied forces have stood by as the Republican Guard crushed the rebels?

In case anyone in Baghdad needed a reminder that Saddam’s rule has been restored as surely as his capital, they need only look to the shore of the Tigris in the exclusive Adamiya district of Baghdad. An enormous building, designed on the lines of a Sumerian palace, has begun to emerge from its scaffolding. It is a new presidential palace.

Shadow of evil

IRAQ

22 January 1995

Latif Yahia spat in the mirror when he saw himself for the first time after being forced to undergo plastic surgery. But it was too late. He now looked exactly like Uday Hussein, the eldest son of the Iraqi president.

He spent the next four years as Uday’s double, a time he now refers to as ‘years of blood’. He was trapped at the heart of one of the most secretive, paranoid and brutal regimes on earth, learning its secrets while treading a tightrope between the pampered privileges of the inner circle and the terror of knowing that he could be shot at any moment.

Yahia has now spoken for the first time about how he was tortured into taking on the role, how he was turned physically and mentally into a terrible imitation of Saddam’s murderous and licentious son, how he eventually escaped, and how he is now trying to exorcise the evil persona that entered him.

He has also revealed that Saddam, like Stalin and Churchill, has his own series of doubles, who are forced to undertake potentially dangerous public appearances. The present ‘Saddam’ replaced one who was assassinated in an attempt on the dictator’s life.

Yahia attended public parties and football matches in his assumed role and posed with soldiers at the Kuwaiti front so that Uday would face no danger but the Iraqi people would believe Saddam had sent his son to serve in the Mother of all Battles. Yahia survived nine assassination attempts.

Only once did he give thanks for his hated new identity. When Yahia finally fled Iraq, soldiers manning checkpoints leaped out of the way and saluted as he sped north in his Oldsmobile, also a double for one of Uday’s cars.

He came to think of himself as a monster. The man he had to impersonate is feared as much as his father in Iraq. He is a spoilt, brutal playboy who flies into uncontrollable rages when crossed and whose violent excesses are covered up by the security forces.

Uday even fell out with his father when he beat to death Saddam’s favourite retainer in a drunken rage in 1988 and was briefly exiled to Geneva. Father and son now appear to be reconciled; last year, Iraqi exiles reported that Saddam had executed three senior military officers after they suggested Uday was not up to the job of defence minister that his father wanted to give him.

Since the Gulf War, Uday has tried to make his image more serious by founding Babil newspaper and a radio and television station that broadcasts popular western entertainment. But Yahia witnessed the sinister private activities of Saddam’s son, which he said included earning millions of pounds from black-market deals in whisky, cigarettes and food while normal Iraqis suffered under international sanctions, and entertaining friends with torture videos shot in his father’s prisons.

Yahia’s story is fascinating, not just as the tale of a man pushed to unbelievable psychological limits, but also because it gives a remarkable insight into the most secretive of worlds, the life of Saddam Hussein and his family.

Now in Vienna as a political exile, the 30-year-old refugee is trying to recover his lost identity. It is disconcerting to meet him. He still looks exactly like Uday, still dresses in the same sharp European suits the dictator’s son favours, sports the same heavy gold jewellery and black Ray-Ban sunglasses. He smokes a Cuban cigar with the same motions and has the same beard that distinguishes Uday from other Iraqis, who have only moustaches.

He is soft-spoken and polite, but old habits die hard. Taking out a cigar, he holds it until somebody lights it, even though the retainers that swarmed around him in his old role as Uday are long gone. He has, however, stopped beating his wife: the violent streak he picked up from his double now sickens him.

Yahia wants to destroy Uday, but he has not changed his appearance because he has no other identity, a dilemma that would have fascinated Sigmund Freud, who lived in the same Vienna street where Yahia’s hideout is.

Yahia’s case is like none Freud ever came across. He grew up in Baghdad, the son of a wealthy Kurdish merchant, and attended the exclusive Baghdad High School for Boys. Uday was in the same class and the two boys resembled each other. ‘But I did not welcome looking similar,’ he said. ‘Uday had very bad manners with people even then.’

After graduating from Baghdad University in 1986 with a law degree, he went off to fight in the Iran–Iraq war, like most young Iraqi males. He was a first lieutenant serving in a forward reconnaissance unit in September 1987 when he received a presidential order to report to Baghdad.

Uday welcomed him in an ornate salon in the presidential palace. There was chit-chat about their schooldays and polite questions about his family before Uday came to the point. ‘Do you want to be a son of Saddam?’ he asked. Wary, Yahia answered: ‘We are all sons of Saddam.’

‘Well, I would like you to be a real son of Saddam, working with me. I don’t want you as protection but as my double.’

Yahia recalled: ‘I was afraid. I knew this was a government of criminals. So I asked him what would happen if I agreed, and what would happen if I refused. Uday told me that if I agreed, “all that you dream will happen”. He said I would have money, servants, houses, women. If I refused, he said, “We will remain friends”.’