Полная версия

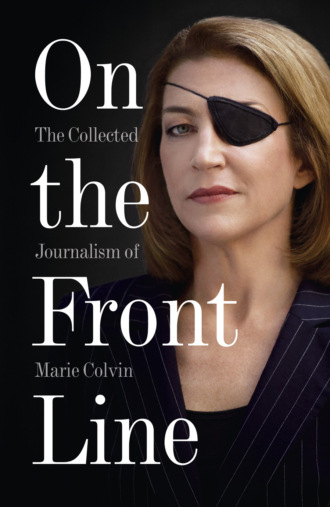

On the Front Line: The Collected Journalism of Marie Colvin

But among Iranians, even former royalists have come round to Rafsanjani as the alternative to radical clerics and renewed revolutionary turmoil. ‘He’s a mullah but he’s the only hope for Iran,’ said a wealthy doctor.

Having squared the rich, Rafsanjani faces a new and much more serious threat. Tehran’s poor southern suburbs, home to the ‘oppressed’ in whose name Ayatollah Khomeini proclaimed revolution in 1979, are seething.

Wages are low, prices mount daily, and housing is hard to find. Hopes raised by Rafsanjani’s election in August are fading fast. The discontent is dangerous. The poor feel they have as much claim to the revolution as the mullahs. Their street protests drove out the shah, and they could do it again.

Anger is openly expressed. Ismail, 34, a shoemaker in the Shahpur bazaar in southern Tehran, was one of Khomeini’s foot soldiers.

‘Everyone around here went out in the streets,’ he recalls. ‘Even the six-year-olds. They promised us everything. They said it was Allah’s land and we would get some of it.’

Ten years later, Ismail pays 40,000 of his 60,000-rial monthly wage (£37) to rent one ground-floor room in which he, his wife and three children eat, sleep and receive visitors. The home is meticulously clean but shabby and cramped.

The family’s energy goes into finding food. Subsidies should make staples such as sugar, rice and cooking oil cheap. But Ismail’s wife cannot remember the last time the government distributed rice in their neighbourhood.

A black market mafia controls food distribution and locals say government officials take bribes. Corruption goes beyond the bazaar. A surgeon said middle-men received state money for drugs but provided cheaper, often toxic, substitutes and pocketed the difference.

Despite the privations, Rafsanjani still enjoys tremendous goodwill among the poor as well as the rich. But Iran’s future will be determined by whether he can overcome radicals in the regime who oppose both his desire to open Iran to the West and to give more freedom to private businessmen at home.

To secure his position he has been quietly dismantling revolutionary committees, set up to enforce Khomeini’s line, and sending their members back to their own jobs.

He also seems to get support from an unexpected source. Khomeini’s daughter, Fatima, said last week she was considering running for parliament in elections due in December. She is intelligent and more astute than her ambitious brother, Ahmed.

She said Rafsanjani’s policies ‘followed the Imam’s mind‘, and she can cite Khomeini’s name with more authority than any radical.

Rumours abound of struggles in the leadership. The strangest concerns a mysterious shipment of gold allegedly linked to radicals trying to finance their own projects.

One night earlier this month national television showed film of two lorries loaded with 10 tonnes of gold ingots, worth $120 million, allegedly captured near the border with Pakistan. Three days later the government announced the bars were in base metal painted gold. Nevertheless the entire smuggled shipment went to the central bank. Ominous graffiti reads: Khar Khodefi ‘You can’t fool us here’.

The unsettled climate comes at a time when Rafsanjani is trying to find an accommodation with the United States so that he can convince foreign investors their money will be secure in Iran. But the situation is stalemated. President George Bush wants Rafsanjani to show good faith by securing the release of hostages in Lebanon. Rafsanjani told western correspondents last week that Iran needed a western gesture of good faith first.

There is so little contact between them that a friendly embassy sends facsimiles of the Tehran Times’s leaders to Washington every day because Americans for a while believed the regime was planting messages for the administration in the newspaper’s editorial page.

Middle East

Soviet settlers jolted by the promised land

ARIEL, WEST BANK

11 February 1990

Dmitri Rafalovsky had just arrived off a flight from the flatlands of the Ukraine. Now he stood in Ariel, a small town in the occupied West Bank of Israel, and stared at the starkly beautiful view.

In the distance he could see picturesque villages with stone houses wedged among unfamiliar hills. Everything looked peaceful in the promised land.

But what he and his wife, Elizabeth, did not know when they arrived here last week was that they had abandoned the Soviet Union with its anti-Semitism and threat of pogroms for a land where the villages they were now looking at housed Palestinian Arabs in revolt against their Israeli masters.

The shock was considerable. ‘What do you mean, this is the West Bank? Oh my God, don’t tell my wife!’ he said. Rafalovsky, 55, knew only too well the dangers; Soviet television had been full of the violence for over a year, although all seemed quiet now. ‘It doesn’t look that dangerous,’ he muttered, doubtfully.

The Rafalovskys are a tiny part of a mass emigration of Jews from the Soviet Union which is changing the demographic map of Israel. Fearful of the changes at home, and witnessing growing signs of hostility and violence, they are flooding into Israel.

The surge has been relentless. Last year 13,000 entered; in January this year 4,500 arrived; in the first week of February no fewer than 1,300 came in.

Because there are no direct flights from the Soviet Union, charter planes are arriving almost daily from East European capitals carrying the latest victims of the diaspora.

The numbers coming in are now so great that the predictions last year of 100,000 look inadequate. Some observers expect between 500,000 and 1m will enter Israel over the next few years, changing for ever a country of just 4m inhabitants.

Rafalovsky, like many of the Soviet Jews who disembarked last week, has only a vague notion of Israel. All he knew was that he wanted to leave the Soviet Union and, with the door to the United States closed, an Israeli visa was the only quick way out.

He was still vague about how he had arrived in Ariel. ‘We were at Ben Gurion airport in the reception office, and the man from Ariel told me it was a small town in the mountains with not many people. He showed me on the map and said, “See, it is in the middle of Israel.” I said it sounded like the place for me.’

It was only dawning on him now that he had arrived in the midst of a controversy equal to anything in the Soviet Union.

Soviet Jews are meant to be able to settle where they like, and there are clear Israeli government denials that they are being encouraged into the occupied territories.

Everyone knows, especially the United States, Israel’s most generous benefactor, that immigration into these lands could jeopardise the already delicate Middle East peace process.

Despite the risks, it became evident last week that the government is concealing how many Soviet Jews are settling there. Figures released on Friday said only 63 had settled in the West Bank. In Ariel alone, however, an estimated 150 people have arrived in the past four months.

It has been a difficult choice for the Rafalovskys. Despite the intifada, they saw advantages in their new West Bank home. Their two-bedroom house is larger than their Kiev apartment, and they have brought their 17-year-old son, Vadim, and Elizabeth’s elderly mother.

They have also been overwhelmed by their welcome. Neighbours have taken them shopping and have invited them to dinner. They have received a government grant for monthly rent, food and Hebrew lessons. Their first days are spent in a daze at the amount of food in the shops and the fact they are in a Jewish state.

Above all, they have escaped anti-Semitism. ‘I have lived with anti-Semitism all my life. I am accustomed to it. But my son is very intelligent and he should have a chance,’ said Rafalovsky.

Nobody underestimates how tough it is for these immigrants to start afresh. Few speak Hebrew. They arrive with only their luggage and $140, the maximum they are allowed to take out of the Soviet Union.

In turn they have triggered euphoria among the normally cynical Israelis, who have agonised about criticism over their treatment of Palestinians. ‘This has made us feel special again. Israelis suddenly feel desired. It’s the same feeling we had after the 1967 war,’ said Gad Benari, a spokesman for the Jewish Agency, which handles the immigration.

But the immigrants do face a problem over their Jewishness. Under Israeli law, all Jews have a right to return to their homeland. This influx, however, is very different from the rush of Soviet ‘refuseniks’ in the 1970s.

They were committed Zionists who had waited in virtual internal exile for exit visas, spending the years studying Hebrew. Few of the new arrivals are religious. Many have never been to a synagogue and are the children of mixed marriages, which will raise problems with the orthodox Jews.

But for now, the benefits outweigh the problems. Most Soviet Jews feel satisfied because they have enough money to live, an apartment and work, however menial.

For most it is enough to escape the Soviet Union. There, Jews are being blamed for the failures of the economy and the uncertainty of the political situation. ‘What I can’t believe is that any of my Jewish friends stayed behind,’ says Victor Savitsky, an engineer who arrived with his wife and their tiny daughter.

Others talk of being barred from universities by anti-Semitism and of the virulently anti-Semitic organisation, Pamyat, which has been holding rallies in cities.

The desire to leave the Soviet Union is now so great that an estimated 12,000 Soviet Jews cannot get seats on planes. The Israelis are trying to persuade the Moscow authorities to allow direct flights to Israel, but for now most immigrants come through Bucharest or Budapest. The Savitskys waited four months before they could buy a plane ticket.

Desperation has bred daring. One couple, Mark and Louisa Puzis, drove their Lada from the Ukraine with their two-month-old baby in the back, trading vodka in exchange for petrol.

Israel is just coming to terms with the magnitude of the problem. The system of absorption is showing signs of falling apart. Reception centres are full and the government budget is overspent.

Critics say the government has been slow to deal with an emerging crisis. Resources in Israel are scarce. There is high unemployment and 20% inflation. ‘We should be treating this like a war situation,’ said Michael Kleiner, head of the Absorption Committee at the Knesset, Israel’s parliament.

He is trying to convince the government to cut red tape and provide money. He has proposed that Israel should stop all development for two years and put that money towards absorbing the new immigrants.

‘Responsible people won’t even make estimates on how many will arrive or how much money we will need,’ said Kleiner. ‘Teddy Kollech [mayor of Jerusalem] has been waiting for 20 years to finish a soccer stadium for Jerusalem. He can certainly wait another two years.’

Love sours for Romeo and Juliet of the West Bank: Avi Marek and Abir Mattar

JERUSALEM

1 April 1990

The script would probably have been rejected by even the most schmaltzy Hollywood producer. Abir, a 19-year-old Palestinian beauty who has gone home to her West Bank village to stay with her mother, meets Avi, a dashingly handsome Israeli officer who spots her when he careers by in his jeep. They go together like humous and pitta bread and talk of marriage.

If the film were ever made, love would no doubt conquer the differences of race, politics and religion. But in the harsh world of the occupied territories, life is more complicated.

Last week, the star-crossed lovers were both outcasts from their communities. Avi was suspended pending the outcome of a military investigation into his breach of the regulations forbidding fraternisation with Palestinians. Abir was hiding in a Palestinian hotel.

The story of Avi Marek and Abir Mattar is a rare glimpse of the human dramas hidden beneath the conventional rocks and riots image of the intifada. Marek is a 30-year-old Israeli captain whose infantry unit is stationed in Beit Jalla, a mostly Christian village that has virtually closed down during the three years of the Palestinian uprising.

Home life held few joys. He had married a much older woman, Rivka, less than a year ago and lived in her flat in a sterile apartment block in the settlement of Gilo outside Jerusalem. But it was better than his own neighbourhood, Shmuel Hanavi, a poor suburb of Jerusalem populated mostly by Sephardic Jews, immigrants from Arab countries.

Marek, who speaks Arabic, by all accounts fell at first sight for Mattar, who was educated in a convent school in Bethlehem and used to babysit for tourist families.

Mattar says it was mutual. In her hotel room last week, she looked at herself in the mirror and smiled when she said: ‘Yes, I love him. We met for the first time eight months ago; we have been happy ever since.’

Sitting looking out on a view of a west Jerusalem street, the Jewish side of the divided city, she reflects on how circumscribed her life has become. She cooks meals on a gas burner in the room and feels out of place among package-trip tourists who fill the lobby. She is also three months pregnant with Marek’s baby.

But Mattar says her life has always been difficult. Her father drank and gambled until her mother kicked him out, and she married at 16 to a man who already had a wife and five children. When he was imprisoned she returned home to Beit Jalla with a child.

Marek began his courtship by calling to her from his army jeep as she walked to a friend’s house. Soon her mother, Nina, noticed she was out all night every night.

‘When I asked,’ she said, ‘Abir replied that it was none of my business. Then I noticed an army jeep would stop outside and beep. The jeep seemed to be around all the time.’

Nina worried that her daughter’s relationship would bring unwanted attention. The Mattar family was already ostracised. Nina’s lifestyle is hardly suited to a traditional Arab village. Last week she dressed to greet visitors in leopard-print stretch pants and a black lace top.

Nina went out to work when her husband left, something that is not done in traditional Arab culture, and had a series of boyfriends before remarrying. ‘I’m not a virgin,’ she said, chain-smoking as she looked out at the village of sun-splashed stone homes. ‘I’ve always had a boyfriend. That doesn’t make me a whore like everyone in this town says. Look at my apartment, if I was a whore I would have made some money. I’ve only one bed and not even a proper bathroom.’

She also collaborated with the Israeli occupying forces. Left with seven children and spurned by her neighbours, she says she felt few loyalties. The police gave her 200 shekels (about £70) every time she passed them information. She stopped when the intifada began.

Before that, such activities meant ostracism. Now, with young teenagers controlling the streets and talking of purifying the Palestinian community, they are life-threatening. About 200 Palestinians have been killed for collaboration or prostitution.

But although Nina warned her daughter she was endangering the family, there was little a mother could do. ‘Their love was burning. Avi was crazy about her and she lost her head.’ The young couple would return together in broad daylight after nights of passion in Marek’s jeep and Mattar would bring him coffee before he returned to his unit.

The family began to receive threats and Marek made things worse. He and his unit began picking up local teenagers and beating them. Nina says she thinks he was trying to show off to her daughter.

Desperate, Nina complained to the police and sent word to Marek’s Israeli wife. The police ignored her but his wife came down and staked out the house in the Arab village. When Marek and Mattar returned, she ran out into the street with a kitchen knife. Mattar made off in his jeep but the story was too public to be kept quiet.

The military suspended Marek. Mattar found a mongrel dog hanging in the family toilet, dead, its head in the water. She quickly left town. Publicity about the case has made it the gossip of Israelis as well as Palestinians.

Mattar says she and Marek plan to marry after they both divorce. She says she will convert to Judaism. ‘I can’t go back to live among the Arabs,’ she said. But she is worried that Marek’s return to Israel may change him. He has been heavily criticised in the Hebrew press.

Marek now faces a military tribunal to explain the liaison. His defence is that he was only fraternising with Mattar in a patriotic endeavour to recruit her as a spy. At the moment observers are not betting on a happy ending to the tale.

Desperately seeking answers in the Arafat slipstream: Yasser Arafat

5 June 1990

The Times

When people know you have spent a year making a film about Yasser Arafat, the question they ask most often is ‘Were you ever afraid?’ At times I felt frustrated, angry, despairing and very tired, but not afraid. In his manner, Arafat is one of the less threatening people you are likely to meet.

Making a documentary of him takes endurance, not courage. We had flown into Tunis for a scheduled interview to begin our filming. But Arafat was in Baghdad. The film opens with a Tunis to Baghdad telephone call. It is 2am and Arafat seems to think the only way we can get a connection in Baghdad in time to meet him is to find a boat to Paris. We agree instead to fly separately to China where he is due for a state visit, then fly back together in his borrowed Iraqi jet.

This scene must cause great pain to BBC accountants. But at the time it seemed the ideal trip. We would film behind the scenes in an exotic location while the terrorist-turned-statesman wheeled and dealed, then have him as a captive interviewee for the hours it took to fly back to the Middle East. The latter was the most alluring. Arafat grows bored in interviews and will often stand up, unclip his microphone and thank you as he walks out.

But the Chinese Foreign Ministry called Arafat while we were somewhere over Pakistan and said: ‘We cannot receive you, the students are causing trouble.’ We headed back to Tunis, arriving in time to board his borrowed Iraqi jet and set off to the summit in Casablanca. But the China trip did pay off. Arafat takes everything personally. Had we decided not to go it would have signalled a lack of commitment, however well-founded our misgivings.

Marie with Yasser Arafat, c. 1994.

When we finally caught up with him, he owed us one. We were instantly famous in PLO ranks as the crew that had gone to Peking to see the ‘Old Man’ and been stood up. Everyone had a similar tale; this time it was not Arafat’s fault, but it usually is. People around him, a travelling entourage that is both family and staff, began helping with tips on the etiquette of living alongside him. One of my journal entries notes a word of advice from a senior aide: ‘When I break your foot, you have gone wrong.’

Arafat’s schedule is exhausting and it wears down everyone around him. Half the hotels in Tunis seem to be filled with people waiting to see Arafat. Fighters with blood rivalries meet in the lobby of the Hilton and turn their backs. Arafat maintains his own rigid personal organisation within the chaos around him. Days are for seeing to problems such as parents seeking university tuition for their children. Serious business takes place at night, dating from the time the PLO was an underground organisation. Meetings begin about 9pm and rarely end before 3am. Everyone is expected to be at Arafat’s call.

He never tells anyone, even close aides, his schedule in advance for security reasons. When you fly with him you do not know your destination until you take off. Asking a simple question at breakfast such as ‘What are you doing today?’ brings startled stares from aides and silence from Arafat.

The PLO is Arafat’s life and he expects the same commitment from everyone around him. He accepts planes and villas from Arab leaders, but remains a nomad and just out of their control. All his villas look the same – sterile, furnished with a print or two of Jerusalem, a television, some nondescript sofas and a desk. The head of the Palestinian government travels in four suitcases: one for his uniforms, one for his fax machine, one for ‘in’ and ‘out’ faxes and one for a blanket to curl up in for cat naps.

His obsessive precision can be maddening. He arranges his keffiyeh headdress meticulously every day in the same way. It must hang down his shoulder in the shape of the map of Palestine. He empties his machinegun pistol precisely as his jet takes off, carefully lining up the bullets on his tray. He marks every single fax sent to the PLO with a felt-tip red pen. But doubts begin to set in when one spends a lot of time around him. Does Arafat really have to read every single fax? Does he have to control every disbursement of funds, the purchase of an office desk in Singapore? It is Jimmy Carter as PLO leader.

Arafat is up on every detail of running the organisation, but never takes time to review policy, listen to advice or plan ahead. The PLO is run from moment to moment from Arafat’s head. The main criticism one hears in the ranks of the PLO is of this autocratic style. Arafat brooks no criticism and, as a result, many educated and independent Palestinians have opted out.

Now, when he desperately needs good advice on the workings of the western world as he tries to convince it that he is sincere in his current drive for a peaceful settlement with Israel, few around him know its ways. He himself is unsophisticated about the West, not surprisingly, as he spent most of his youth organising a resistance movement and has been banned from most of it for his adult life.

So why do Palestinians follow this unlikely leader? In person, Arafat is warm and inspires devotion. Palestinians who disagree with his views respect his devotion to the cause. He has always managed to compromise and lead by finding the highest common denominator within the fractious Palestinian movement. Arafat has no political ideology. He wants one thing: to liberate the homeland of his people. He has become more than a leader. For most Palestinians he is a symbol of their aspirations.

Arafat today is a desperate man. He is 60, has no heirs, and wants to achieve something tangible before he dies. In renouncing terrorism and recognising Israel in 1988, he played his best card and cannot understand why he has not received more support from the United States in convincing Israel to make a similar concession.

Arafat is now flying around even more obsessively than when we were filming, trying to stave off attacks from radicals within his own organisation and from Arab states who say he has given everything in return for nothing. Arafat is hoping to convince enough people to stay with him, hoping to keep the organisation together long enough, hoping to stay alive long enough, so that he can one day land his own plane in Palestine.

Home alone in Palestine: Suha Arafat

19 September 1993

When Yasser Arafat went to Washington, his wife stayed in Tunis. But she wasn’t hiding away. Marie Colvin profiles the determined Mrs Arafat.