Полная версия

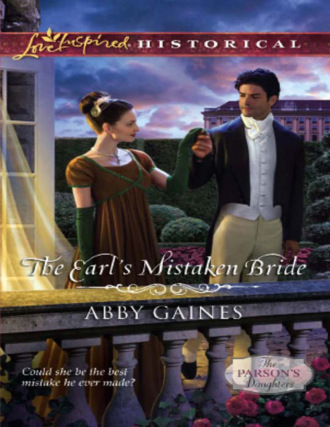

The Earl's Mistaken Bride

Her father thumbed the cleft in his chin. “My dear, his reputation is not spotless.”

“None of us is perfect,” Constance pointed out.

“True,” her father agreed.

“Constance, you don’t find him a little proud?” her mother asked.

“Margaret!” The reverend shifted on his chair, which wobbled, causing him to mutter ominously.

“Much as I admire your reluctance to condemn people, Adrian,” Margaret Somerton said, “Spenford is widely regarded as a proud man. I preferred him before he became the heir.”

“Mama, he was just a boy,” Constance protested. “The man is always different from the boy.”

Marcus had been born the second son of the previous Earl of Spenford. Stephen, his older brother by six years, had been by all accounts the perfect heir. Until he died in a hunting accident when Marcus was fifteen.

“A delightful boy,” Margaret corrected her. “Until his father, who by the by was also a proud man, took him in hand.”

“I don’t find Lord Spenford at all proud.” The event that had informed Constance’s opinion would seem trivial to her parents. But three years ago she’d realized Marcus Brookstone was a man worthy of her deepest feelings.

“All I’m saying is, you’re not obliged to accept this offer,” her mother said. “Your father’s future may be uncertain, but we are confident God will supply.”

Constance didn’t know how, even with their faith, her parents could remain so calm. Her father’s insistence on taking the Word out to the laborers in the fields, or wherever they might be, had landed him in trouble with his bishop. He’d been accused of Methodism, of creating a schism in the parish. It was monstrously unfair, when her father held unity and inclusiveness within the church as one of his dearest tenets. There was a risk the bishop might remove him from the parish; her parents would lose their home and livelihood.

“I don’t expect any of you girls to marry if you don’t wish it,” the rector confirmed. “St. Paul himself said it’s better not to marry if one can be content in the single life, and while my heirs will never be wealthy, you will live in modest comfort. But blessed as I have been in my own marriage—” he reached across to squeeze his wife’s hand, almost oversetting his chair “—it wouldn’t surprise me if God’s providence should include loving husbands for at least some of my daughters.”

Constance’s youngest sister, Charity, vowed frequently to live with Mama and Papa the rest of her days. But in truth, Constance had expected to be the spinster of the family.

With four sisters prettier than she, she was used to going unnoticed by all, with the exception of her parents. And perhaps of older people, like the dowager countess, who seemed to find her plainness soothing.

Though the local young men were scrupulously polite in greeting her, in asking her to dance after they had danced with her sisters, no marriageable man had ever, as far as she was aware, seen her. Looked past her sisters, past all other young ladies, and chosen her.

Marcus Brookstone had.

Her mother said dubiously. “I hope the earl will know how lucky he is to win you, Constance.”

“How blessed he is, my sweet,” her husband corrected her. Though in many ways the most tolerant of men, he didn’t allow luck to be given credit for divine Providence.

Constance took a deep breath. “Papa, I believe God has given me this opportunity, and I wish to accept his lordship’s proposal. I am certain we can make each other happy.”

Chapter Two

Had he changed his mind?

Five minutes past eleven o’clock on Constance’s wedding day and no sign of a bridegroom for the ceremony that should have started on the hour.

Standing in the churchyard, trying to appear nonchalant while her body vacillated between chills and extreme heat, Constance was conscious of all eyes upon her. Most discomfiting.

She could almost feel sorry for Isabel and Amanda, the two of her sisters acclaimed as beauties. To be stared at so intently… Constance shivered in the spring sunshine.

“Cold, my love?” Isabel asked. Instilled with the supreme confidence that came with beauty, she wouldn’t understand Constance’s petrified state.

Constance shook her head. “Thank goodness you added this veil to my bonnet,” she said to Amanda. “At least I don’t have to meet the eyes of everyone wondering if the earl plans to make an appearance.”

“Veils are all the rage in London and Paris,” Amanda said, oddly defensive.

Constance patted her arm. “I trust your knowledge of the fashions, dearest, for you know I have none.” She considered taking back the reticule and small posy of flowers Amanda was holding for her, but there was too much chance her nervous fingers would shred them.

“It looks very becoming on you,” Amanda said. She’d used the same French lace for the veil as Constance’s mother had for the elegant trim she’d added to Constance’s best blue muslin dress. Without compunction, Margaret Somerton had cut into a beautiful tablecloth that had been a gift from her own mother.

The trim made a fine feature on an otherwise simple dress, drawing attention away from Constance’s face, and down to her figure. The veil, anchored to her bonnet with a cream-colored satin ribbon and reaching to her chin, achieved the same end. Constance dared not ask where Amanda had obtained the ribbon. Her sister managed to fancy all her clothes with furbelows that Constance suspected were gifts from young men.

“You realize, Amanda, as Countess of Spenford I will be in a position to offer you a London Season,” Constance said. “Perhaps next year…” So long as they weren’t in mourning for the dowager, of course. Amanda had yearned for a London Season for as long as she’d known such a thing existed.

Amanda merely squeezed Constance’s hand. Maybe she still had the headache she’d complained of earlier when she’d begged to be excused from the ceremony. Constance had in turn begged her to attend. It was bad enough to be getting married lacking one sister’s presence—there hadn’t been time to send word to Serena in Leicestershire and have her travel home to Piper’s Mead.

Now, that seemed a good thing. Serena might have had a wasted trip.

The villagers were growing restless, despite the valiant attempts of Reverend Somerton and his wife to engage them in conversation. While most of the men were working, a good number of the women thronged the churchyard, eager to witness the most prestigious wedding in the village for at least a generation. A couple of lads had taken advantage of the festive atmosphere to station themselves on the churchyard wall, normally forbidden territory. They nudged and jostled each other, enjoying the risk of an imminent fall.

“Maybe his lordship had an accident,” Mrs. Penney, the baker’s wife, suggested. “Could be overturned in a ditch on the London road.”

“Or footpads,” said Mrs. Tucker, from the Goose & Gander. “They’ll kill a man soon as look at him, these days.”

“No!” Constance said sharply.

“Sorry, love,” Mrs. Tucker said. “Don’t you worry, his lordship won’t let you down. He’s like his father in that respect. A stickler for his duty.”

Even as she spoke, Mrs. Tucker glanced at Isabel, confusion written on the older woman’s broad face. She was doubtless wondering why any earl would choose Constance over Isabel, whose fair beauty had been a source of village pride since she’d been in the cradle.

“You look lovely, Constance.” The assurance came from Charity, who, although just turned fifteen, displayed an unusual sensibility for other people’s feelings.

Constance smiled her thanks, though her sister probably couldn’t see through the veil.

Constance had never wished for beauty…at least, not since she’d accepted, years ago, that she would always be the most ordinary of the Somerton girls. Not that her face sent small children screaming for their mothers, or anything like that. She’d spent enough hours in her youth searching the mirror for signs of beauty to know her brown eyes were warm, her eyebrows nicely shaped. Those features ensured she was acceptable. And she’d inherited her mother’s excellent figure, for which she was truly grateful.

It was just…on this day, when she was about to marry one of the most handsome men in all England, she would have given much to be pretty.

“God sees the heart,” Charity reminded her, still reading Constance’s thoughts. “Perhaps He has revealed your gentle heart to the earl.”

“Perhaps,” Constance said doubtfully. She hoped the Lord hadn’t revealed her besottedness to Lord Spenford—the poor man would be mortified to know his bride cherished such romantic notions for a near stranger.

She could only hope it was indeed her gentle spirit, whether revealed through divine guidance or through the dowager, that had caused the earl to settle on her.

One of the urchins perched on the churchyard wall shouted, “He’s coming! And he’s got a bang-up rig, too.”

His mother boxed his ears for referring to Lord Spenford as “he” rather than “his lordship” and for daring to express an opinion on the earl’s conveyance. The women set to straightening their dresses, adjusting their bonnets in a panicked flurry that reminded Constance of the Bible parable about the foolish virgins readying themselves for the bridegroom.

Constance stayed still. No minimal adjustment would elevate her to sudden beauty.

“Mama,” Amanda said, “I think I’m going to faint.”

A stir of interest ran through the crowd at her words, dividing attention between her and the churchyard gates.

“Oh, gracious.” Margaret Somerton was visibly torn.

“Stay there, Mama,” Amanda told her. “I’ll sit in the side chapel until I feel better. Excuse me, Constance.”

“Of course, love. I should have let you rest at home.”

Amanda did look wan. There was no sign of the dimple in her left cheek that had inspired several young men to attempt poetry, with woeful results. As she handed over Constance’s reticule and posy, she asked with a strange urgency. “Connie, this is what you wish, isn’t it? To marry Spenford?”

It wasn’t like Amanda to show such care for others; Constance blinked away unexpected tears. “It’s what I wish more than anything,” she confirmed. Hoping it was true.

Almost before she finished speaking, Amanda was hurrying into the church. And Constance’s attention was drawn to the fine curricle pulling up behind the dowager’s coach, sent earlier from Palfont to convey the Somerton women to the church.

Constance didn’t recognize the gentleman driving the curricle, nor did she notice the groom on the back. She had eyes only for her betrothed, sitting alongside the driver.

Poor Lord Spenford would be exhausted, having traveled so far the past few days. Marcus, I must learn to call him Marcus.

But the moment the curricle stopped, he jumped down with an energy that made a mockery of her concern.

His dark hair lifted in the breeze as he strode toward her father. The crowd melted back in a flurry of curtsies and, from the boys, removal of caps.

“Sir, forgive me.” He shook her father’s hand. “We encountered an overturned post chaise on the road out of Farnham and stopped to render assistance.”

An impeccable reason for tardiness. Constance wouldn’t wish to marry a man who failed to render assistance.

Her father inquired of the injured passengers, declared his intent to pray for them.

“May I introduce you to the Marquis of Severn, who will stand with me as groomsman,” Marcus said.

His friend, the same impressive height as the earl, but to Constance’s eye not as handsome, exchanged bows with the reverend. Reverend Somerton introduced his wife to the Marquis…goodness, would the formalities never end?

Then, suddenly, they were finished, and her father was beckoning to Constance.

Isabel gave her the slightest of shoves; Constance made her way on trembling legs.

She dropped a tiny curtsy, afraid if she sank too low she would never rise again. To nurse a girlish dream was one thing; to live the reality quite another. I can’t go through with this.

The earl took her hands in his, an intimacy she hadn’t expected. His fingertips curled beneath hers, warm through the fabric of her best gloves, anchoring her.

“My dear Constance.” His smile held kindness, chagrin and an uncertainty that somehow boosted her confidence. “How fortunate I am that your nature aligns with your name, and you have waited for such a tardy wretch. Will you do me the honor of accompanying me into the church?”

Her gaze darted over his shoulder to the worn stone building she loved as well as her own home. She would enter the church a parson’s daughter; she would leave it a countess. A wife. His wife.

The earl’s grip tightened. Her doubts lifted like mist warmed by the sun, to drift away on the breeze.

“I will,” she said.

He brought her left hand to his lips, and through her glove pressed a kiss to her knuckles. Warmth flooded her, traveled directly to her legs where it had a bizarre weakening effect. Constance locked her knees, put all her energy into holding her ground.

“Come,” Spenford said, “let us be married.”

“I, Marcus Albert Edward Spencer Brookstone, Earl of Spenford, Baron Brookstone, take thee, Constance Anne Somerton…”

Constance calmed her nerves by focusing on the string of names. And reflected she would be more pleased if he were mere Marcus Brookstone.

Her father recited the next portion of the vows in the dear, measured tone that had guided her life. “To have and to hold…to love and to cherish…”

He spoke clearly, rather than loudly, but the words rang to the rafters above the heads of the enthralled congregation.

“To have and to hold…to love and to cherish,” the earl repeated firmly.

Constance let out a breath of relief. He had sworn to love her. Not today, or tomorrow, necessarily, but he would try, and when he succeeded it would be—

“Till death us do part…”

Yes. That.

She made the same vow, her voice shaking, adding the bride’s promise to obey.

Behind her, she heard a small sob. Mama. Pragmatic Margaret Somerton had surprised her daughters, and herself, with several bouts of sniffling over the past few days. Her mood had been unimproved by her husband’s assurance she was not losing a daughter, but gaining a son.

Constance slid a sidelong glance at her mother’s new “son.” At several inches taller than she, at least six feet, his height was potentially intimidating.

“Do you have the ring?” her father asked.

The earl—Marcus—turned to his groomsman. Constance had forgotten his name… Severn, that was it, the Marquis of Severn.

Severn handed over a circlet of gold. After a moment’s pause, Constance realized everyone was waiting for her.

She fumbled to free her left hand—the one he had kissed—from her glove. Marcus took her bare fingers, and for the first time they were flesh to flesh. About to be made one.

“With this ring, I thee wed,” he repeated after her father.

Another few moments, and the gold band slid down her finger. Making her his.

Constance’s mind shied away from the thought.

“Those whom God hath joined together, let no man put asunder,” her father intoned.

The next phrases washed over her, until she heard, “I now pronounce that they be man and wife.”

Constance’s gazed snapped to the earl. She hadn’t even been listening to that final declaration and now she was married. Just as well she didn’t attend to omens, because surely…

The worry evaporated in the warmth of the gaze Lord Spenford—her husband!—turned on her.

A half smile on his lips, he reached for her veil, lifted it.

His brilliant blue eyes scanned her face.

Constance smiled shyly.

Marcus’s mouth straightened into a line that could only be described as grim.

“My—my lord?” Words died away as Constance absorbed his expression.

He looked appalled.

Chapter Three

“Who the blazes are you?” Marcus snapped the moment they attained the privacy of the carriage.

The girl—the woman—his wife, blast it!—shrank back against the seat, her bonnet with that veil, that—that instrument of deception, askew.

“You know who I am.” Her voice quivered as she rubbed her elbow where he’d gripped it to escort her from the church. “I am Constance… .”

She stopped. As if she had been going to say Constance Somerton, but that was no longer true, because now she was—

She could not be Lady Spenford.

Outside, the villagers cheered and shouted good wishes as the coach pulled away, headed for the rectory, for the wedding breakfast.

Thoughts and images whirled in Marcus’s head, blurred by fatigue. Could some artifice—cosmetics, perhaps?—have made her look so different last Monday? Her voice was slightly altered, but in the church he’d attributed that to nerves.

“Remove your bonnet,” he ordered.

She clutched it to her head. So much for that promise she’d made not five minutes ago to obey.

He leaned forward; she gasped as his fingers closed around the ribbon beneath her chin. Then she froze as he worked the knot, careful not to touch her.

He lifted the bonnet from her head, tossed it to the floor of the coach. Which elicited another gasp.

“Your bonnet is the least of your worries, madam,” he said roughly. His gaze raked her face. Not at all the same. Brown eyes, not violet-blue, a perfectly ordinary nose in place of the charming version he’d seen on Monday. Thinner lips, a chin that might be described by someone in an uncharitable mood as pointy.

Marcus was in a very uncharitable mood.

In place of ink-black curls, this girl’s hair was a drab brown, drawn up in a knot, with a few tendrils curling around her nape.

“What is this trick?” he growled. “You must have planned it before I even arrived in Piper’s Mead. I swear, if your holier-than-thou father played a part in this—”

“You will not say a word against my father,” she blurted.

And now she dared issue orders to him!

Well, that wouldn’t last, nor would this marriage. He’d been duped into marrying this plain-faced fraudster, and fraud was grounds for annulment. There’d been the case of Baron Waring, some years ago…Marcus couldn’t remember the details, but the woman involved had misrepresented herself, and the bishop declared an annulment.

The girl, Constance, or whatever her name was, picked up her bonnet. As she settled it on her lap, it slipped through her trembling fingers and fell to the floor again.

Instinctive courtesy had Marcus reaching to retrieve it at the same moment she did. His fingers brushed hers, and she flinched.

“I would like an annulment,” she announced.

Marcus jerked backward, the unfortunate bonnet once again hitting the floor. He hoped the infernal thing was damaged beyond repair.

“You want an annulment?” He’d heard of women hatching preposterous schemes to entrap a titled husband, but he’d never heard of a scheme that included a request for an annulment.

She tilted that chin—definitely pointy—at him. “On—on grounds of insanity.”

“You admit to a weakened mind?” So much the better!

She blinked and her brown eyes widened. “Sir, you are the insane one.”

Marcus’s mouth opened and closed, and he had the uncomfortable sensation that he looked like one of the carp in the Japanese pond at Chalmers, the main Spenford estate.

He suspected such an expression did not convey complete, calm rationality.

She knotted her fingers in her lap, which seemed to firm her voice. “I have heard married ladies talk of an illness that gentlemen can acquire as a result of—of dissolute living.” Her cheeks flamed. “It drives them mad.”

“You accuse me of dissolute living?” he said dangerously.

Her gaze dropped, then rose again. “Papa warned me your reputation is…not quite spotless.”

Marcus felt himself reddening. Outrageous! What kind of man was Somerton to talk to his daughters in that way?

She didn’t realize how perilously she trod, for she continued. “It occurs to me that perhaps you chose a bride from Piper’s Mead because…”

She didn’t finish. She didn’t need to. Her implication was clear: because no lady of sense in London would have him.

“I am pleased to inform you my health is perfect,” he snapped.

“Which implies you are deliberately accusing me and my father of dishonesty,” she warned.

“I apologize,” he said, teeth gritted, aware that she hadn’t apologized for her suggestion that he lived an improper life. But he had to admit, she seemed as baffled by the situation as he was. Surely a parson’s daughter could not have cooked up this wild scheme. He breathed out through his nose, calming himself. “May we start this conversation again, in an attempt to untangle this confusion?”

“I suppose so,” she said dubiously.

As the coach swung into the lane that ended at the rectory, Marcus grasped the strap overhead. “What is your name?”

Her guarded expression suggested she still harbored suspicions he was a half-wit. “My name is—was Constance Anne Somerton.”

Marcus tipped his head back against the seat. “I met Constance Somerton in Piper’s Mead on Monday, and believe me, she looked nothing like you.”

She frowned, putting a little furrow in the middle of her forehead. “That’s not possible.”

“I suspect she was younger than you—” this woman looked all of her twenty years “—with dark, curly hair and eyes an unusual blue. She called herself Miss Constance Somerton.”

His bride pressed her fingers to her mouth, and he remembered how they had felt, fine and slender, in his grasp.

“Amanda,” she moaned.

He pounced. “Is that your name? Amanda?”

She didn’t quite roll her eyes, but only, he sensed, through heroic self-restraint. “I am Constance. Amanda is my sister. She is of somewhat…mischievous temperament.”

“You call passing herself off as you mischievous?” he barked. “I asked your father if I could marry her!”

She closed her eyes. “Of course,” she murmured. “It wasn’t me you wanted at all.”

He had thought that perfectly obvious from the moment he’d lifted her veil.

“How could I have been so stupid?” She sounded broken.

Marcus felt a twinge of concern. But he was virtually a stranger to her; she had no reason for heartbreak. This was likely part of her act. “Certainly one of us has been stupid,” he said bitterly.

To his horror, tears sprang to her eyes. Marcus averted his gaze as he offered her his white linen handkerchief.

But she held up her hand, palm out in refusal. “I want nothing from you.”

For the barest moment, her dignity impressed him…then he remembered, she’d already duped him once.

“Of course you don’t,” he said. “You can buy all the handkerchiefs you want, thanks to the generous settlement documents your father signed on your behalf this morning.”

Those tears clung to her lashes, held there by force of will, it seemed, not spilling onto her pale cheeks. Marcus stared at the ceiling of the carriage as she fumbled in her reticule, presumably for a handkerchief of her own.

Instead of a scrap of fabric, she pulled out a folded sheet of paper. “What’s this?”

“I hardly think I would know,” he said coldly.

She opened the note. “It’s Amanda’s hand.”

At the mention of her “mischievous” sister, Marcus plucked the paper from her fingers. “Allow me to read it to you.”

It wasn’t a request.

The opening words of the missive, written in a girlish hand, jumped out at him.

Forgive me!

Foreboding filled him as he began to read aloud.

“‘Forgive me! Constance, darling, I have done something very Dreadful, and you will think me Wicked. On Monday, I encountered Lord Spenford in the Village… .’”