Полная версия

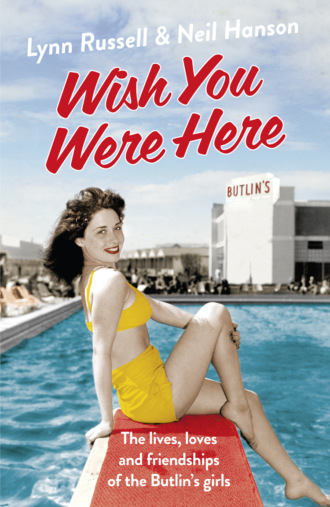

Wish You Were Here!: The Lives, Loves and Friendships of the Butlin's Girls

Even those with smaller children were liberated from their responsibilities to a certain extent. While parents ate at the oilcloth-covered tables in the dining hall, the under-twos were fed their puréed beef and carrots and stewed apple in a separate ‘feeding room’ in the nursery, where rows of babies in highchairs ate their baby food away from the other campers – or at least that was the theory. The babies were supposed to stay there until their parents and older siblings had finished their own meals in the dining hall, but the babies often had other ideas and would howl the place down until their parents collected them. Some put their little children in their prams outside the dining-hall windows, lining them up so that the babies could see their parents through the window. One camper recalled that, even from the other side of the glass, the babies’ screams could be heard above the clatter of cutlery and the noise of conversation.

Parents were also free to dance in the ballroom, watch a show in the theatre or drink in the bar in the evenings, while ‘chalet patrols’ – nursery staff in their blue uniforms and capes – marched or cycled up and down the lines of chalets, listening for crying babies. Freed from the burdens of childcare and factory or domestic drudgery for a week or two, many couples also rediscovered the pleasure they had taken in each other’s company in the early years of their relationships – although for others, the unusual amount of time spent with their partner could also have the opposite effect!

In 1957 Hilary and her friends went to Butlin’s at Skegness for the first time. Four of them went, sharing one chalet. Hilary’s brother had a car, a Morris 1000, and he offered to take them there, so they all squashed in with their suitcases piled on the roof rack and set off. They had driven only a few miles down the road when the car broke down. When they should have been driving in through the gates of the camp at Skegness, they were still sitting in the broken-down car, waiting for a tow truck.

It was pouring with rain all day and by the time they got to the camp they were tired, bedraggled and fed up. Like all the girls, Hilary’s friend Brenda was on her first trip away from home, and her mother had bought her a brand-new suitcase to take on holiday. It was so wet that the handle disintegrated and fell off as she was carrying it through the camp. Despite the trials and tribulations of getting there, however, as soon as they saw Butlin’s, they absolutely fell in love with the place.

All along the road leading to the camp there were tall flagpoles with different-coloured flags flying, and there was always a row at the front of every Butlin’s camp, too. ‘You could see them flying from about a quarter of a mile away,’ one camper recalled, ‘and as you drove up to the main entrance, the first excitement was seeing all those flags blowing in the wind. When I saw that, I knew that I wouldn’t be seeing much of my parents for a whole, wonderful week.’

As they turned in through the gates, the girls could see the tropical blue colour of the big outdoor swimming pool, and the theatres, dining halls and other main buildings, all freshly painted in brilliant white with the details picked out in bright primary colours. Rocky Mason, a former redcoat and entertainments manager who spent most of his working life at Butlin’s, can still recall similarly vivid memories of his very first sight of Butlin’s as a boy. He’d grown up in ‘a very dreary city, covered in mill smoke. It was very dull and the sky was always grey. When I got to the camp I felt as if I’d suddenly walked into utopia – it was so colourful, so warm, so friendly. There were lights across the roads, there were banners fluttering in the breeze, there seemed to be music coming from every direction. The swimming pool was the most beautiful, beautiful thing I had ever seen, there were flags all around the pool and it was a stunning colour of blue. I saw rows and rows of chalets, all with different-coloured doors and windows – red, yellows, blues, greens, orange – it was just a gorgeous place to be and there seemed to be laughter coming from every building.’

Hilary couldn’t have imagined a greater contrast with Bradford, which was a very wealthy city then but also a very drab and grey one. There was a near-permanent pall of smoke hanging over the city, fed by hundreds of mill chimneys, and the golden-coloured sandstone of the buildings was stained ink-black by decades of coal smoke and the sulphurous winter smogs.

The rest of Britain was just as dreary during the 1940s and 1950s. The last phase of wartime rationing only ended in the mid 1950s, and even though ‘utility’ clothing was no longer the only option, clothes were still invariably made of wool or cotton, in black or muted shades of green, brown or grey. Television – for those families that owned a TV set; it was still a luxury item – was broadcast in black and white. The first colour television broadcast in Britain did not occur until 1967. Radio was still dominated by ‘received pronunciation’ and the Reithian requirement to inform and educate, rather than entertain. And even in the late 1950s or early 1960s, most of the music played on the BBC Light Programme would have been equally familiar to listeners in the 1930s. Given this backdrop, the Butlin’s camps, with their rows of colourful flags, bright-blue swimming pools and dazzling white buildings with vividly painted doors and windows, must have looked positively psychedelic to 1950s eyes.

Butlin’s was impressive enough by day, but by night it was staggering. You could see the glow from all the lights from miles away – and there were thousands of them. It had the same level of impact then that Las Vegas has today, and Hilary and her friends had simply never seen anything like it. She couldn’t get over how huge the camp was, either (when full, it held something like 12,000 people then), and the lines of chalets seemed to go on forever.

The individual chalets themselves weren’t quite so impressive. They were tiny, and had a little sink in the corner with a small mirror over it, a curtain across a tiny alcove to serve as a wardrobe, a small table, one chair and four iron, army-surplus bunk beds. That was it. Hilary remembers noticing that the bedspreads matched the curtains – blue with white yachts on them – and that the same motif edged the tiny mirror above the sink. Butlin’s kept these the same for years. Although there wasn’t much spare room, it suited the girls fine. They were only sixteen or seventeen, and until then they’d always been on holiday with their parents, staying in boarding houses or campsites. Hilary doesn’t think any of them had ever even stayed in a hotel, so to be off on their own, with their own separate chalet, tiny though it was, seemed quite sophisticated.

The redcoats made quite an impression on Hilary, too. The girls all looked very smart and glamorous to her, but they were friendly, too, and seemed to be absolutely everywhere, organising everything, making sure everyone was having a good time. Hilary and her friends had a ball while they were there, dancing every night, chatting and flirting with boys, and generally doing all the things their parents wouldn’t have approved of. Some of the girls even destroyed their holiday snaps before they went home – not because they were doing anything particularly wrong, but the photographic evidence of them just talking to boys or having a drink or cigarette in their hand would have been enough to get some of them, including Hilary, into serious trouble.

It continued to pour with rain for almost the entire week. The only fine day was the Friday just before they went home, so they spent the entire day, Hilary says, ‘running in and out of the chalet, changing our clothes and then taking another set of photos so that when we went home, we could show our friends the photos and make it look like we’d been having wonderful weather and a really great time every day of the week!’

Despite the weather, they had all loved their first holiday at Butlin’s – so much so that before they left to go home they all said: ‘We’re definitely coming back, and what’s more, we’re going to have two weeks next year.’ So as soon as they got home, they booked the next year’s holiday and began saving for it straight away. By the time the second year came round they all had steady boyfriends, and Hilary was actually about to get engaged to hers – a boy called Dave – but nothing, not even that, was going to get in the way of her holiday, so she took a deep breath and said to him: ‘All of the girls are going on holiday together. We booked it a year ago and even though I’m going to be getting engaged to you, I’m still going on holiday with them, without you.’

She’s still not sure what she would have done next if he’d said that he didn’t want her to go, but he just shrugged and said, ‘Okay,’ so that was that.

That second year, 1958, there were twice as many of them: eight girls, four to a chalet. The camp was packed with crowds of people all having a good time, and as they strolled around, the group of girls met up with gangs of boys and chatted and flirted with them, and then went dancing in the ballroom every night. Even though none of the girls really drank, they would still call in at Ye Olde Pigge and Whistle early in the evening. The bar was huge and had a fake tree in the middle of the room and a half-timbered, mock-Tudor ‘street’ down one side, with the ‘windows’ opening onto the bar. It was just as bizarre as it sounds! They’d stop in there for a little while, chat to the boys and have a soft drink, and then they’d go to the ballroom. They would still be there, dancing away, when the boys all came through after the bars had shut, and then they’d be dancing with them and generally having a good time until the ballroom closed down for the night.

One night they were chatting to a group of boys, and one of them was a real joker. He wasn’t tall or short, broad or skinny, or particularly handsome, but he stood out from the crowd and Hilary can still clearly remember him. This lad was asking Hilary what she thought she was going to do with her life when one of her friends butted in and said: ‘Don’t bother asking her. It’s too late for her, she’s already spoken for. She’s getting engaged when we go home.’

He just looked Hilary straight in the eye and said, ‘It’s never too late, until you’re standing at the altar in front of that man with his collar on back to front, saying “I will”.’

She just laughed at the time and thought no more about it, but when she got home, what he’d said kept coming back into her mind. She did get engaged to Dave and, as girls did in those days, she began saving and putting things away for her ‘bottom drawer’. She might buy a pillow case one week, a towel the next and a saucepan the following week, and put them all away in the bottom drawer of her dressing table, ready for when they set up home together. ‘It was how people did it in those days,’ Hilary says. ‘You had to save for everything and buy it a bit at a time, whereas now people just go and buy what they need on credit, all in one go.’

At that point in her life, Hilary could easily have gone ahead and got married, and would probably have had a child before she was twenty, but she went to the cinema with Dave one night and there was a travel documentary showing, the short film they always put on before the main feature. ‘Usually I was bored to death with them,’ she says, ‘but this time, as I was watching this film showing all these exotic places in different parts of the world, I thought to myself: you’re only eighteen, and there’s a whole world out there you haven’t seen and know nothing about. There and then I decided that I was too young to get married and wanted to see a bit more of life before I was ready to settle down, so I broke off the engagement with Dave straight away. He was a lovely lad and he took it very well. I mean, he was upset at first – we both were – but I was sure I’d made the right decision and I didn’t go back on it.’

Hilary went back to going dancing every night with her friends and was really enjoying herself. None of them were engaged or married, or even going particularly steady with anyone, so, still inspired by that short film she’d seen, Hilary said to them: ‘Why don’t we all go off somewhere together, like Australia, or Canada, or anywhere, really? There’s got to be more to life than we’ve seen so far. Let’s go and find out what we’ve been missing!’

It wasn’t that she was unhappy at home; she had a very happy home life. Her parents had just moved from the back-to-back terraced house she’d grown up in to a new house on an estate called Holmewood. ‘It’s not got a good reputation these days,’ she says, ‘but when they moved in there, just after it was built, it was wonderful. It had a bathroom and all the mod cons that we’d not had before.’ So her life was comfortable, she was happy enough and not short of anything, but she just felt that she wanted to do something else and see more of the world than Bradford.

So in early 1960 Hilary and her three closest friends made up their minds that, yes, they’d go off somewhere together and have an adventure! Based on little more than the fact that it had looked beautiful and very different from Bradford on the travel documentary Hilary had seen, they decided they would all go to Canada, so they applied for visas, got all the forms and filled them in. However, a couple of the girls then started to get cold feet, and the other one started going out with a boy and didn’t want to leave him, so in the end Hilary was the only one ready to go. She didn’t feel let down or fall out with the girls about it – ‘They were very good friends to me then, and I’m still friends with them over fifty years later. I go on a night out with them all every now and again, and two of them still live in the same village as me now’ – and it didn’t shake her own determination to do something different before she settled down.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.