Полная версия

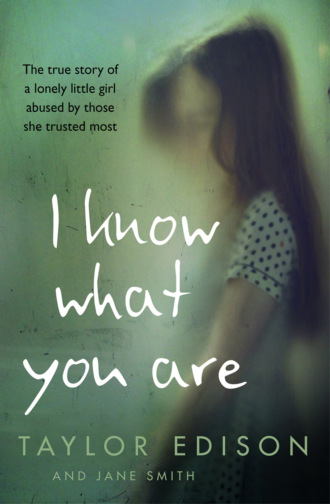

I Know What You Are: The true story of a lonely little girl abused by those she trusted most

I don’t have many specific memories of Mum either being there or not being there during that period of my childhood. I know she was still smoking a lot of weed, so perhaps she was there more than I remember, but in the background somewhere, unnoticed in the noisy chaos of all the lives being lived around her. What I do remember is that Mum didn’t cook and I was always hungry. She didn’t enjoy cooking, so she simply refused to do it, even when Dan was out at work all day and there were five children who needed to be fed. When Dan was at home, he made just two things: porridge and spaghetti Bolognese. But mostly we ate takeaways.

After we had lived for a few months in the house with the muddy bathroom floor, Dan’s alcoholism began to get really bad. Even when he was working, he must have struggled to pay the bills for all of us, plus whatever he spent on alcohol for himself and weed for him and Mum. Things got even tighter when he started turning up at building jobs drunk at 9 o’clock in the morning and getting sent home. Eventually, when he stopped working altogether, he would sit around in the park all day, drinking with the other alcoholics who went there to while away their jobless hours.

Then, one day, Dan’s kids simply disappeared. I didn’t know what had happened to them: one minute they were there, teasing or tolerating me; the next minute they had gone. It wasn’t until much later that I found out they had been taken into care. Apparently, after moving on from using me as a decoy for their shoplifting exploits, the two boys had begun to get involved in more serious forms of petty crime. Then one of my stepsisters got an infection and was taken to hospital, where she was flagged up as ‘at risk’.

There were lots of things that didn’t make sense to me at that time – and there are many things that still don’t. But although I might not have understood what being taken into care meant, it would have been better if someone had given me some kind of explanation rather than none at all. As it was, the sudden, mystifying disappearance of my four stepsiblings was just one more of the many incidents that occurred during my young life that made me feel anxious and insecure.

Fortunately – perhaps – I always managed to escape the attention of social services as a child. I think there were two reasons for that: because Mum always kept me away from hospitals and because I was always clean and reasonably well dressed in clothes that were shabby but appropriate for my age. The reason for the first explanation was that Mum had been in care herself as a child and didn’t want me to experience whatever it was that had happened to her. The reason for the second seems to have been that as long as I wasn’t dirty, obviously malnourished or underweight, the social workers who never quite became involved in my childhood assumed I was being adequately looked after.

You can’t really blame the social workers for being fooled and for just scratching the surface. They must have seen lots of children who were more obviously at risk and more in need of their attention. And I think, particularly as I got older, they sympathised with Mum for having to cope with such an exhaustingly difficult child.

Eventually, and inevitably, the drink consumed Dan and he and Mum split up. When he moved out of the house with the muddy bathroom floor, I moved into the small bedroom in the attic, although, as it didn’t have a bed, I actually slept with Mum in her room. Then, after a while, Mum rented out the third bedroom to a series of lodgers, who seemed to come and go without incident, providing Mum with a small income for the minimum amount of hassle.

It was the first time it had been just Mum and me, but she was often too busy doing whatever it was she did to have time to bother with me. And as I hated being on my own, I was more or less forced into trying to make friends with some of the local kids. The problem was, even though I had started school by that time, I had absolutely no idea how to go about it. The way I had been brought up until then was almost feral: as long as I didn’t cause Mum any trouble, I was pretty much left to do whatever I wanted. Now, all I really wanted was to have a friend. But it’s hard to make friends when you don’t have a clue how to socialise.

One of the things I found most difficult about any kind of interaction with other people was the fact that what they said often seemed to be completely contradicted by what they did. Because I couldn’t interpret people’s body language and took everything at face value, sarcasm was entirely lost on me. And because I didn’t understand people’s reactions, I didn’t ever learn from them. So if kids were mean to me, I would be puzzled and hurt and then go back the next day and make the same mistakes all over again.

I did make one friend, after a few false starts. He was a boy who lived down the road from us, and although he teased and bullied me whenever he saw me, I kept going back and just following him around. Then, one day, he pushed me into some stinging nettles and I ran home, sobbing, with every exposed inch of my body covered in painful red rashes. I went back the next day though, and this time he let me tag along. Maybe he thought I had guts and he decided to give me a chance. But it wasn’t courage that sent me back there. The way he treated me was the way I had been treated by my stepbrothers, and therefore I didn’t expect anything different. And for someone as desperate as I was to have a friend, someone who ignored me was better than no one at all. So being allowed to tag along was more than I could possibly have hoped for.

For a while, I was more than happy to be someone’s tag-along. It was certainly preferable to what was happening at school.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.