Полная версия

Why Bowie Matters

Strictly speaking, yes, he was a Brixton boy; he was born on that street, at number 40. But his family moved when he was barely six, and he lived in Bromley from January 1953 onwards, including a full ten years in the same house on Plaistow Grove. Brixton in south London sounds better as an origin than Bromley in Kent, as Bowie surely realised when he dropped tall tales about getting into local ‘street brawls’ that made him ‘very butch’ and growing up in an ‘’ouseful of blacks’. Brixton, in the early 1950s, was a borderline between the past and the future, where bombsites and ration books were reminders of the recent war, but where the sights and tastes of a more multicultural, modern London had begun to creep in. One neighbour recalls technicolour clothing, Caribbean vegetables, even jugglers and sword-swallowers at the local market, while Bowie describes the streets around Stansfield Road as ‘like Harlem’. Bromley, on the other hand, apart from its associations with H. G. Wells, is known primarily for bland suburbia: biographer Christopher Sandford mentions it as a ‘drab, featureless dormitory town’, and Bowie referred scathingly, in a 1993 interview, to its regularity, its conformity and its ‘meanness’. For much of his life, he preferred to write it out of his official history.

But think about your own childhood: where you were born, and where you actually grew up. I was born in Coventry and spent my earliest years there in a council flat, but by the time I turned three my parents had moved to the first of many short-term lets in south-east London. I only half remember those from photographs, unsure if my memory is of the image or the real place; and I don’t recall Coventry at all. Certainly, I was born there, but the streets I’m from – the streets that really formed me – are the ones around Kinveachy Gardens in Charlton from ages three to eleven, and then Woodhill, down the hill in neighbouring Woolwich, as a teenager.

Did his first six years in Brixton shape David Jones? To some extent, no doubt. ‘I left Brixton when I was still quite young, but that was enough to be very affected by it,’ he later claimed. ‘It left strong images in my mind.’ He apparently returned to Stansfield Road in 1991, asking the tour bus to stop outside his old house, and came back for a final pilgrimage with his daughter in 2014. But Brixton’s influence must surely pale compared to the formative decade, from ages seven to seventeen, that David Jones spent at 4 Plaistow Grove, next to Sundridge Park Station, in Bromley. There is, as yet, no statue, plaque, or mural there – just occasional flowers outside someone else’s residential house – though he recalled it in 1993’s ‘Buddha of Suburbia’, with one of those lyrics that seems a gift to biographers: ‘Living in lies by the railway line, pushing the hair from my eyes. Elvis is English and climbs the hills … can’t tell the bullshit from the lies.’ ‘I knew him as Bromley Dave,’ Bowie’s childhood friend Paul Reeves confirmed, years later. ‘As that is where we were both from.’

When I attempted to immerse myself in Bowie’s life and career, between 2015 and 2016, I followed the path he’d traced around the world, from New York to Berlin to Switzerland to New York again. I also spent time at his old haunts in London, reading his recollections of the La Gioconda coffee shop at 9 Denmark Street while sitting in the same spot, currently a Flat Iron steak restaurant. But while I’d visited his home streets in Bromley – Canon Road, Clarence Road and Plaistow Grove – I’d only paid passing attention to the area. With hindsight, there was an unconscious reason behind the omission.

My old manor, around Kinveachy Gardens and Woodhill, is about six miles from Bowie’s house in Bromley; close enough that we both knew each other’s territory, growing up. He travelled to Woolwich at least once, to see Little Richard at the Granada. My experience and his also overlapped in Blackheath and Lewisham, equidistant between our childhood homes: we both visited friends in the posh big houses of Blackheath and travelled to Lewisham for its superior shops. There are key differences, of course, and I’m flattering myself by imagining a connection between us. When Bowie caught the bus to Lewisham to buy shoes and shirts, he jumped off it two stops later with ‘Life on Mars?’ already in his head. In significant ways, then, my experience in Woolwich was not like David Bowie’s in Bromley: but there are interesting cultural continuities, despite our difference in age. Our town centres had a lot in common, for instance: a Littlewoods with its school uniforms and jam doughnuts; the knives, forks and tomato-shaped ketchup dispensers in Wimpy’s very English hamburger restaurants; ornate, art deco Odeon cinemas on the edge of town. Because Bromley already seemed familiar to me from my own childhood, I didn’t delve as deeply in, or investigate it, in such detail. So in May 2018, I reopened the investigation. I went to live in Bromley, to revisit Bowie’s time there. I ate there, drank there, slept there and shopped there, walking his old routes.

To me, research – and critical thinking in general – is not so much about finding information as it is about making connections: drawing lines, linking points and sometimes making unexpected leaps across time and space. If you plotted them visually, the paths of my research process would form a network, a matrix: a conceptual map, expanding and developing and becoming increasingly more complex.

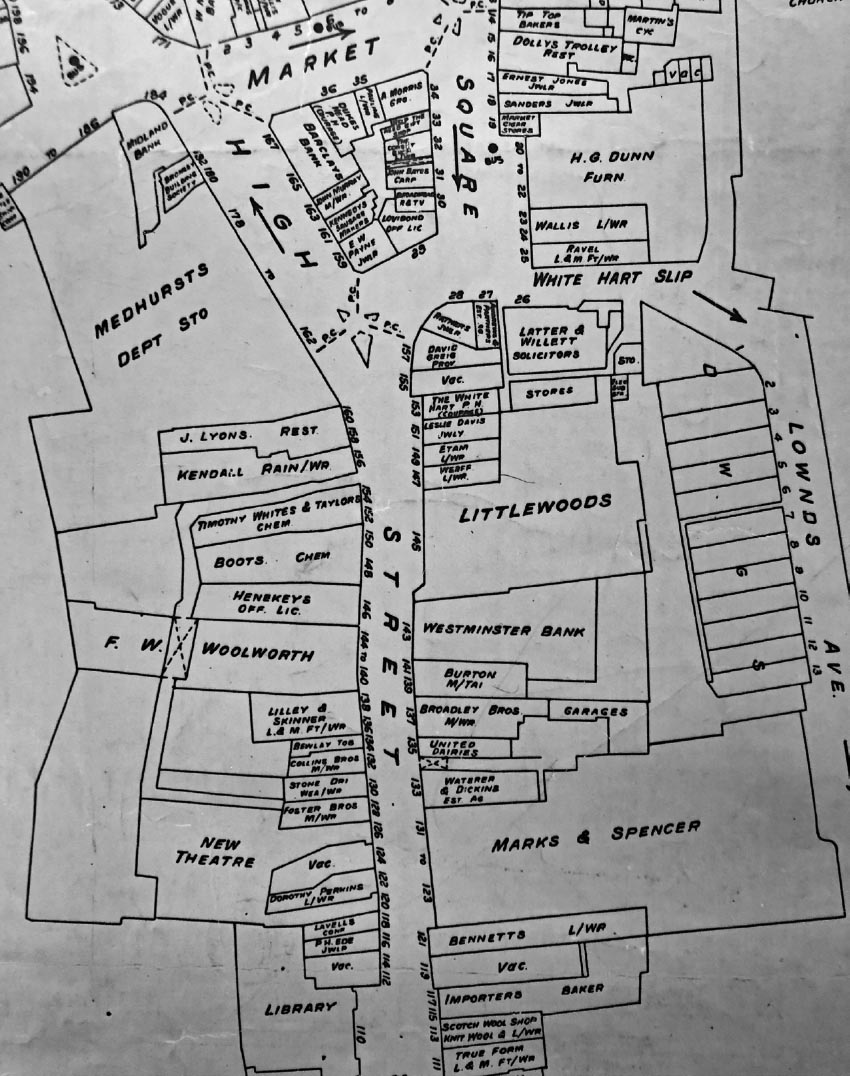

I started with a map: with two maps. The Goad Plan, a gigantic, hand-drawn map of Bromley in the 1960s, spread across a table in the library’s Historic Collections room, and a far smaller, digital version alongside it on my phone – 2018’s Google Maps app – which I scrolled across for comparison. The same place, separated in time.

There is little sign now of the smaller boutiques and quirky, independent shops that would have been part of David Jones’s cultural landscape – the Tip Top Bakery, Sherry’s Fabrics, Terry’s Stores, Dolly’s Trolley – though there is a Tips and Toes nail salon, and Buddy’s Café. Some of Bromley’s newer shops and venues offer an ersatz simulation of the past. Mr Simm’s Olde Sweet Shop is a franchise dating back to 2004, and Greater than Gatsby, a bar promising 1920s style, warns its punters: ‘Guys, no hats or hoodies, come on, you’re not 12.’

Medhurst’s Department Store, where Bowie bought his American vinyl and listened to records in the basement sound booths, is now a Primark. Wimpy’s, where he ate burgers with his school-friend Geoff MacCormack, indulging his tastes for America, is the Diner’s Inn Café. The nearby Lyons’ Corner House, where teenagers could gather over coffee, has also vanished – it’s now a Mothercare – though there’s still a music store, Reid’s, with saxophones in the window.

I sat at the Stonehenge Café, opposite Primark, and watched the Market Square and High Street with a double vision. It wasn’t hard to imagine a teenage David walking through the doors – past where the Aladdin Sane T-shirts are now hanging – to meet his girlfriend Jane Green, who worked on the record counter, for a covert smooch to Eddie Cochran and Ray Charles. ‘Can’t Help Thinking About Me’, says one of Bowie’s 1960s singles. I couldn’t help thinking about him. One of his last songs – released posthumously, on 8 January 2017 – was called ‘No Plan’. His final tracks in particular feel like a puzzle he left behind, a message for his followers. What was his plan, during the 1960s? Did he have any sense of his end goal? Was he working his way towards fame, or just enjoying the scene, the lifestyle, the groups and the girls, like so many other teenage boys who loved records and made their own music?

Pulling the digital map back from the High Street to a wider view, we can begin to plot Bowie’s Bromley on a broader scale. Most of the key landmarks in his early life are all within walking distance of each other; I proved it to myself by walking between them, putting the legwork into my research. Only Bowie’s secondary school, Bromley Tech, was out of easy reach; he used to take the number 410 bus. It’s now Ravens Wood School, and I visited it for the final chapter of this book.

Plaistow Grove is less than a mile north of the town centre. I took a right at the Hop and Rye pub, then walked down College Lane, passing St Mary’s Church, where a seven-year-old Bowie sang in the choir with his friends George Underwood and Geoff MacCormack. Nearby is a chip shop that dates back to 1920: I wondered if the lads got a takeaway there, as I did. Their Cub Scout pack, the 18th Bromley, is still based at the church, and meets every Friday. Past Plaistow Green, a well-tended grassy square, it’s another fifteen minutes down quiet, safe streets to David’s former primary school, Burnt Ash.

The Bromel Club, in the Bromley Court Hotel, is another mile from Plaistow Grove, along London Lane. Bowie played there with the Lower Third in 1966, aged nineteen: it was a prestigious gig, in a venue that also hosted the Yardbirds, the Kinks and Jimi Hendrix. The exterior has barely changed, but the Jazz Club became a ballroom, which became the Garden Restaurant, a gorgeous space of curved archways and elegant pillars. There are photos of Bowie with a mod haircut on display in the hotel reception, with a mounted single of his early songs with the Lower Third and The Manish Boys.

Sitting in the restaurant, I studied a different kind of matrix: a list of names and numbers, from an old reference book called Kelly’s Directory. It told me exactly who had lived on Bowie’s street and in the surrounding area in specific years. Even the abbreviations carried an air of quaint, pre-war convention. Every George was shortened to Geo., every William was a Wm. There were Herberts, Cuthberts, Cyrils and Arthurs; the Misses Austin, Miss Osborn and Miss Gibbs. I spoke to residents who’d lived on Plaistow Grove at the same time as Bowie. Some of them remembered him, or had stories about him passed down from previous generations. One told me that her nan saw David with his mother regularly at Mr Bull’s greengrocer shop. ‘She always tied coloured ribbons in his hair as a toddler because she wanted a girl. No wonder he turned out weird!’ Bromley’s older locals confirmed the shops around the corner from the Jones family, all the owners known politely by their surname. Mr and Mrs Bull had a dog called Curry. The Kiosk, selling sweets at Sundridge Park Station, was run by Miss Violet Hood; then there was Coates electrical engineers, Arthur Ash boot repair, Bailey’s the newsagent, a butcher’s shop run by two brothers, and a hair salon variously known at different times as Beryl’s or Paul’s.

Plaistow Lane, the main road, slopes slightly uphill before the turn on to Bowie’s home street. A painted sign brands the area as Sundridge Village. On a sunny evening in spring, it looks like a great place to grow up. David Jones’s neighbours did not change at all between 1955, when he was eight, and 1967, when he turned twenty. There was Miss Florence West, to the left at number 2, and to the right, Mr Harry Hall; Mr George Rowe lived at number 8, and Mr and Mrs Pollard at number 10. None of them moved in or out during those twelve years. On that specific, local level, Bowie’s life on Plaistow Grove seems consistent to the point of being comatose.

Walking down the short, quiet street from the main road to his house – morning, Miss West, good morning, Mr Hall – you can easily imagine an ambitious, imaginative and creative teenager becoming bored. From his back bedroom he could hear the trains from Sundridge Park on their way to London, and the music and boozy crowds from the pub, the Crown Hotel, at the end of his garden. I talked to a resident who’d occupied the same room, after the Jones family left. She explained that you couldn’t hear the trains anymore, now that the windows were double-glazed. Times change. The Crown is now Cinnamon Culture, an upmarket Indian. I sat in the beer garden. You can see what would have been his bedroom window, from the back, and imagine him again, looking out at the lights, the trains, the adults in couples and groups; listening to the music from the pub as it mixed with his American radio broadcasts, and longing for escape.

Of course, it’s only imagination. We can establish certain facts, but then we choose how to fill in the gaps. Without Bowie’s long-promised but never-written autobiography, we can only rely on available documentary evidence like maps and directories, and the recollections of his friends, family members and acquaintances, decades later. But judging by the jokes, provocations and outright lies that constitute many of Bowie’s interviews, can we really assume that even his own memoirs would be any more reliable?

Every biography of Bowie, even the most authoritative, is a constellation created by joining together a scatter of stars into a convincing picture. It is a particular route, plotted across the points of a map, which leaves some paths untravelled. It is a selection of ideas and evidence from the Bowie matrix – the vast network of what we know about this public figure and private man – which emphasises some details, and discards others. That’s the nature of research and writing: not just the discovery of information but the way we join it up; what we omit, as well as what we include. A history of Bowie – like any other history – is a story, based around selection, interpretation, speculation and deletion. It has to be, because if biographers simply absorbed and channelled all the available information about Bowie’s life, it would overwhelm any sense of conventional narrative and character: put simply, it wouldn’t even make sense.

In 1967, for instance, Bowie told a New Musical Express journalist that he’d moved with his family not to Bromley, but to Yorkshire when he was eight. He claimed to have lived with an uncle in an ancient farmhouse, ‘surrounded by open fields and sheep and cattle’, complete with a seventeenth-century monk’s hole where Catholic priests had hidden from Protestant persecution. The NME journalist commented helpfully that it was ‘a romantic place for a child to grow’. There’s a seed of truth in what sounds a purely fanciful story: Kevin Cann’s Any Day Now: The London Years, built around well-documented details, suggests that David did visit his Uncle Jimmy in Yorkshire for holidays in 1952 and fabricated these trips into an extended stay at a later age. Yet even this contradicts Bowie’s simultaneous assertion that he lived in Brixton until the age of ten or eleven and walked to school past the gates of its prison. Authors Peter and Leni Gillman dug into educational archives to confirm that David Jones transferred into Burnt Ash Juniors, Bromley, on 20 June 1955. The school is seven miles from Brixton Prison, which makes it very unlikely that a ten-year-old took that detour. Historical records and maps, with their prosaic evidence, are duller than Bowie’s stories about his past, but more reliable.

Can we trust the memories of the people who grew up with him? Dana Gillespie, one of Bowie’s first girlfriends, memorably describes a trip to his parents’ ‘tiny little working-class house … the smallest I’d ever been in’. She thinks they had ‘little tuna sandwiches … it was a really cold house, a very chilly atmosphere.’ There was a television ‘blasting away in the corner, and nobody spoke’. She repeated the anecdote for Francis Whately’s 2019 documentary, David Bowie: Finding Fame, adding a postscript: ‘It was hard going. It was soulless.’

David Jones’s mother Margaret, known as Peggy, is similarly described by his former school-friends as cold and unaffectionate: ‘I don’t think it was a family,’ remembered Dudley Chapman. ‘It was a lot of people who happened to be living under the same roof.’ George Underwood agrees: ‘Even David didn’t like his mum. She wasn’t an easy person to get on with.’ Geoff MacCormack remembers telling Bowie that Peggy ‘never quite took to me’, receiving the rueful confession in response that ‘she never quite took to me, either.’ Peter Frampton suggests that David had a better relationship with his teacher, Owen Frampton – Peter’s dad – than he did with his own father, Hayward Stenton (known as ‘John’) Jones. ‘I’m not privy to the relationship … but I don’t think it was that great.’

George Underwood, by contrast, recalls John Jones as ‘lovely, a really nice gentle man’, while Bowie’s cousin, Kristina Amadeus, points out that David’s dad, who ‘absolutely doted on him’, bought him a plastic saxophone, a tin guitar and a xylophone before he was an adolescent, and that ‘he also owned a record player when few children had one … David’s father took him to meet singers and other performers preparing for the Royal Variety Performance.’ The Jones’s house may have seemed tiny to Dana Gillespie, but to Kristina, it was ‘lower middle class … his father was from a very affluent family.’ Uncle John, she tells the Gillmans, ‘really wanted him to be a star’. Note that despite these many documented friendships and relationships with cousins close to his age, Bowie reports of his childhood that ‘I was lonely,’ and also recalled: ‘I was a kid that loved being in my room reading books and entertaining ideas. I lived a lot in my imagination. It was a real effort to become a social animal.’

Despite the supposed coldness of the Jones family home, Bowie reminisced in the late 1990s about roast dinners on wintry Sundays, with a small fire blazing, and his mother’s voice soaring to match the songs on the radio. ‘Oh, I love this one,’ she’d remark, joining in with ‘O For the Wings of a Dove’, before haranguing John Jones for thwarting her musical ambitions. David Buckley’s biography describes her as a ‘drama queen’ with a frustrated dream of ‘being a singer, being a star’, while John was ‘naturally nonconfrontational’. Frigid, unaffectionate, not really a family; or a warm, even heated environment, with a drama-queen mother and a softly-spoken dad who used his industry connections, his experience as head of Dr Barnardo’s publicity department, and his comfortably middle-class salary to support his son’s ambitions?

Bowie’s former manager Kenneth Pitt, meanwhile, gives an impression of 4 Plaistow Grove that contrasts with Dana Gillespie’s chilly image; and his version of Peggy is also far more doting. ‘It was a very conventional suburban home, a tiny terraced house, very comfortable and very homely … and there I’d sit in the front room, talking about David, and his mother would tell me, “You know, he was always the prettiest boy in the street, the sort of boy that all the neighbours loved.”’

Biographer Christopher Sandford adds to the complexity of this family portrait. David’s father was ‘irrepressibly proud of his son’ but also ‘dour, taciturn and tight-fisted – a cold man, an unresponsive man’ who had a stream of affairs and was ‘very prejudiced … very’. Peggy, by contrast, was ‘loud, fractious and given to bewildering mood swings’, yet also ‘inhibiting and aloof’. Sandford finds quotes from Bowie to support this perspective: his father ‘had a lot of love in him, but he couldn’t express it. I can’t remember him ever touching me’, while a compliment from his mother ‘was very hard to come by. I would get my paints out and all she could say was, “I hope you’re not going to make a mess.”’

Peggy herself told an origin myth of Bowie. When he was three, she explained to a journalist in 1985, he’d taken an ‘unnatural’ interest in the contents of her make-up bag. ‘When I found him, he looked for all the world like a clown. I told him that he shouldn’t use make-up, but he said, “You do, Mummy.”’ It’s a neat story, and it echoes her son’s memory of being scolded for playing with paints, as well as his later glam, drag and Pierrot personae. But with hindsight, knowing what David Jones became, it’s understandable if those who knew him, even his mother, tend to tell stories that fit the finished picture, and if biographers, in turn, choose those as the building-blocks of their books. Our sense of David Jones’s childhood is a mixture of non-fiction, invention and half-truth, shaped retroactively by everyone’s awareness of what happened next. The adult Bowie – sometimes literally – rewrites the past of young Jones, and those who knew him tend to follow suit.

Underwood, for instance, remembers that David boasted precociously to the school careers adviser, ‘I want to be a saxophonist in a modern jazz quartet.’ Owen Frampton recalls the Bowie of Bromley Tech as ‘quite unpredictable … already a cult figure’. Dana Gillespie claims Bowie told her, at age fourteen, ‘I want to get out of here. I have to get out of here. I want to go up in the world.’ A neighbour tells Sandford that Bowie used to stand in the glow of the Crown pub’s coaching-lantern, ‘anticipating his pose as Ziggy Stardust’. Another relative recalls that he stood up in front of the TV, aged nine, and announced, ‘I can play guitar just like the Shads … and he did’ – even though the Shadows didn’t appear in public until David was eleven. The local anecdote about Peggy taking her infant son to the shops with ribbons in his hair – ‘No wonder he turned out weird!’ – falls into the same pattern. Even the midwife who delivered baby David in 1947 supposedly pronounced, eerily prefiguring the image of Bowie as angel messiah, that ‘this child has been on earth before’. His music teacher, Mrs Baldry, is unusual in her careful refusal to fuel the Bowie myth. ‘He was no spectacular singer. You’d never have picked him out and said, “That boy sings wonderfully.”’ Bowie’s own revisions of his past, of course, don’t help. ‘I’ve always been camp since I was seven,’ he claimed. ‘I was outrageous then.’ His tendency to retcon his own origins – to suggest that the seeds of his later strangeness and stardom were already rooted in childhood – is particularly evident in his 1970s interviews, when he was keenly forging his media brand.

‘Can’t tell the bullshit from the lies.’ As ever, Bowie’s lyric was knowing. The truth, inevitably, lies in an amalgam of all these testimonies – the interviews, the reminiscences, the dry documents – with the likeliest possibilities emerging in the overlaps between stories, or in a combination of apparently contradictory reports. A house can be tiny, poky and cold to one visitor; tiny, cosy and warm to another. A man can find it difficult to express physical affection towards his son, but show his love by buying him instruments and introducing him to celebrities. A mother can praise her boy as the prettiest in the street, but still feel wary of him playing with her make-up. A woman can sing without shame to the radio over a family Sunday dinner, and still seem aloof or uncomfortable in front of a fourteen-year-old girlfriend. A teenager can have many friends and still feel lonely.

The information we have about Bowie in Bromley (and in London, and Berlin, and New York) is a complex mosaic: Dylan Jones’s David Bowie: A Life, a collection of short interviews from which some of the quotations above are taken, is a perfect example of a book’s form echoing its subject. Bowie is, essentially, a kaleidoscope of multicoloured fragments, constantly shifting. We can identify patterns from the shapes, but someone else can look again from a different angle, and twist a little, and see something new. Our knowledge of him is a complex network, where two conflicting ideas can both have been true at once. ‘Some writers have struggled to put all this in a logical sequence,’ he told journalist George Tremlett in the late 1960s. ‘I wouldn’t bother if I were you.’

Why does this matter? It matters to remember that David Bowie did not descend to earth in 1947 but spent the longest stretch of his younger years in that tiny home on Plaistow Grove and in the streets surrounding it. He wasn’t hanging out with glam rockers and groupies, but with Peggy and John Jones, with George and Geoff and Peter, and sometimes Kristina, and sometimes his half-brother Terry Burns. Ten years before Ziggy, he was the fourteen-year-old in his school photo, with a winning, wonky grin, a neat haircut and two perfectly normal eyes.

He was, in many ways, like the hundreds of other boys at Burnt Ash and Bromley Tech. He was also far from the only local lad to form a band as a teenager: his first group, The Konrads, was already well-established, with George Underwood as the vocalist, by the time David was allowed to join in June 1962. David Jones had talent and ambition, but so did a lot of young men in his social circle. Somehow, he made himself exceptional. Somehow, he emerged from this environment and created an act – a work of art – that the world had never seen before. The story matters because anyone could have done it, but only Bowie did: and the fact that a boy who grew up in Bromley could forge the persona of a world-conquering glam rock messiah is surely more inspiring to the rest of us than the idea that Bowie simply arrived from space, fully-formed.