Полная версия

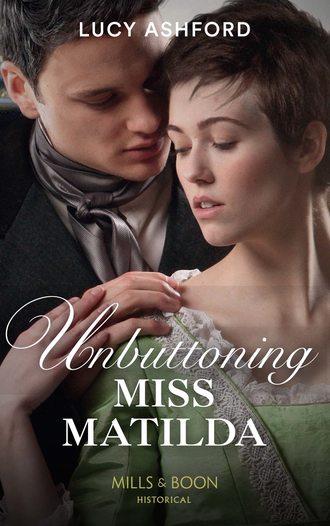

Unbuttoning Miss Matilda

A convenient companionship...

...and a passion neither expected!

Former army officer Jack Rutherford is on the run—he must go to Aylesbury to prove his innocence! Opportunity strikes in the unconventional form of Matilda Grey, who needs help to pilot her canal barge. Jack is captivated by her unusual beauty, vulnerability and resilience. But traveling together in such close quarters, their mutual craving becomes as impossible to ignore as the secrets that still lie between them...

LUCY ASHFORD studied English with History at Nottingham University, and the Regency is her favourite period. She lives with her husband in an old stone cottage in the Derbyshire Peak District, close to beautiful Chatsworth House, and she loves to walk in the surrounding hills while letting her imagination go to work on her latest story. You can contact Lucy via her website: lucyashford.com.

Also by Lucy Ashford

The Major and the Pickpocket

The Return of Lord Conistone

The Captain’s Courtesan

The Outrageous Belle Marchmain

Snowbound Wedding Wishes

The Rake’s Bargain

The Captain and His Innocent

The Master of Calverley Hall

Discover more at millsandboon.co.uk.

Unbuttoning Miss Matilda

Lucy Ashford

www.millsandboon.co.uk

ISBN: 978-1-474-08924-1

UNBUTTONING MISS MATILDA

© 2019 Lucy Ashford

Published in Great Britain 2019

by Mills & Boon, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London, SE1 9GF

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition is published by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, locations and incidents are purely fictional and bear no relationship to any real life individuals, living or dead, or to any actual places, business establishments, locations, events or incidents. Any resemblance is entirely coincidental.

By payment of the required fees, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right and licence to download and install this e-book on your personal computer, tablet computer, smart phone or other electronic reading device only (each a “Licensed Device”) and to access, display and read the text of this e-book on-screen on your Licensed Device. Except to the extent any of these acts shall be permitted pursuant to any mandatory provision of applicable law but no further, no part of this e-book or its text or images may be reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated, converted or adapted for use on another file format, communicated to the public, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of publisher.

® and ™ are trademarks owned and used by the trademark owner and/or its licensee. Trademarks marked with ® are registered with the United Kingdom Patent Office and/or the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market and in other countries.

www.millsandboon.co.uk

Note to Readers

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Contents

Cover

Back Cover Text

About the Author

Booklist

Title Page

Copyright

Note to Readers

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Epilogue

Extract

About the Publisher

Chapter One

London—June 1816

Jack Rutherford hauled himself up from the mattress on the floor, poured water into a bowl and began to wash. The water was ice cold, but he scrubbed his face and chest all the harder because he damned well deserved the discomfort. For the third morning in a row, he’d left it till nine o’clock to struggle out of bed—and what was more, he had a hangover clanging like a set of church bells inside his head.

You, he told himself, are an almighty fool.

He looked around the cramped attic room. Now, where on earth were his clothes? Lying in a heap on the floor, of course, exactly where he’d flung them before falling asleep at past three this morning. He began putting them on. Buckskin breeches and a frequently mended linen shirt. An old leather waistcoat and a pair of scuffed riding boots. After glancing at the mirror hanging lopsidedly on the wall he ran one hand through his tousled black hair, noting that his jaw was dark with stubble.

He looked like a ruffian. Felt like a ruffian. The morning sun pouring in through the high window was hurting his eyes and his head—and it was all his own stupid fault, because he’d drunk far too much brandy last night at Denny’s gaming parlour.

He was twenty-six years old and his life was going precisely nowhere. Yes, he’d made some money at the card tables, but he needed to make a lot more and fast.

He clattered down two flights of twisting steps to emerge in a ground-floor room that was crammed with relics of the past, all set out on dusty shelves and counters. Then after pulling open the shutters and unlocking the front door, he stepped out into the cobbled lane and gazed back at the building from which he’d just emerged. A faded sign painted with the words Mr Percival’s Antiques hung over the door, although ‘Antiques’ was, in this case, a polite way to describe utter junk.

As for the rest of the street, it was crammed on both sides with terraces of three-storeyed shops and eating houses in various states of disrepair. His abode was distinguished by a window displaying just a sample of the wares inside—chipped chinaware, clocks that didn’t work and dog-eared books. Yet when Jack had taken on the lease two months ago, he’d been assured by Mr Percival himself that the business was a gold mine.

Jack had been dubious. ‘It’s a bit off the beaten track, isn’t it? Paddington?’

‘On the contrary! You’ll find, my dear Mr Rutherford, that the fashionable set from Mayfair and Westminster simply love to drive out to west London in their carriages, so eager are they for historic rarities with which to embellish their town mansions! Now, we decided on a six-month lease, did we not? And you are to pay me twenty guineas for all contents and fittings—are we agreed?’

‘Agreed,’ Jack had said warily, shaking Mr Percival’s hand. He’d had a splitting headache that day as well—again, the result of too much brandy and too little sleep the night before. He hadn’t a clue about antiques—still hadn’t. But he’d known he had to do something to earn his living, something other than winning at cards, because winning made you enemies.

So Jack became an antiques dealer and he had tried to make a success of it, he really had. For the first two weeks he’d opened every morning at eight without fail, dusting the displays of bric-a-brac and cheap jewellery, making valiant attempts to impose some kind of order. Prices? He hadn’t a clue, but he took a guess and stuck on labels galore. He slept on a mattress in the attic, he bought lunch from the nearby pie shop at midday and drank his ale in the local public house.

He also acquainted himself with his neighbours. To his left was a furniture maker, though Jack saw him only rarely, since he appeared to spend his days drinking gin in a back room. To the right was the pie shop run by two lively girls called Margery and Sue, and they did rather better business, as did the noisy alehouse just beyond, which served the boatmen from the canal wharf close by.

All in all there were certainly plenty of people around, but as for the carriages of the rich rolling up, for the first two weeks there wasn’t one—in fact, to begin with, Jack’s only visitors were other dealers, all of whom glanced around and said something like, ‘You’ve a heap of worthless stuff here, haven’t you? I’ll take it all off your hands for a few pounds and believe me, I’ll be doing you a favour.’

Jack shook his head. But at the same time he was noticing that their rather greedy eyes always alighted on the items that actually were starting to sell. War relics.

It was almost a year since the long war with the French had come to an end and, in London, many unemployed ex-soldiers drifted around on the streets. Though they had little enough money in their pockets, quite a few still possessed relics of their soldiering days: items such as belts and knives, brass buttons from old army jackets, pistols and spurs.

Jack got talking to some of them one night in an alehouse. ‘I’ve an idea,’ he’d said. ‘I’ll see if I can sell these things for you.’ So he paid for a small advertisement in The Times.

For Sale at Mr Percival’s Antiques Repository in Paddington.

Military Mementoes of Wellington’s Campaigns

The day after that advertisement appeared, a smart carriage rolled up outside Jack’s premises and an exceedingly well-dressed man entered. ‘I’ve come,’ he announced pompously, ‘to see these military mementoes of yours, young fellow.’

* * *

Half an hour later, another rich man arrived, then another. ‘Ah, the heroes of Salamanca and Waterloo!’ they would declare as they gloated over the pistols and spurs. Each time, Jack nodded politely. Each time Jack concealed his silent contempt for their fascination for these relics of war, guessing that they’d faint on the spot were they to get one glimpse of the horrors of a battlefield. And he made them pay—oh, yes—in hard cash.

But his calculations told him he was making just about enough to cover the rent, no more, which meant that some time soon he’d have to make a major decision about his future. As for now, it was surely time for a belated breakfast—and just down the road he could see a girl selling fresh-baked bread from a laden basket. He went to buy a couple of warm rolls, then strolled on, eating as he walked, to where the narrow street opened out to offer a completely different view.

For here, in front of him, was the newly built canal basin—Paddington Wharf. Thanks to this fresh waterway link with the north, the whole area heaved with industry and commerce. Jack walked on almost to the water’s edge, where boat after boat were moored.

This busy scene fascinated him. The canal was busy from dawn till dusk with boats arriving from the Midlands, mostly laden with coal which was rapidly—noisily—transferred on to the waiting carts and taken to be stored in the nearby brick warehouses. The bargees, he’d noticed, scarcely paused to draw breath because the minute their loads were delivered they set to work again—the men, their wives, their children—to scrub down their boats, refill the holds with timber or grain, then once more head north.

It was mighty hard work for the boatmen—hard work, too, for the horses who hauled the laden vessels, although those horses, he’d noticed, were tended with as much care as a cavalryman would lavish on his mount. As it happened, just then Jack’s eyes were caught by a big grey horse that was being led right past him, its halter firmly held by a youth in a long coat and battered, wide-brimmed hat.

The horse stopped to look at Jack inquisitively and he reached out to stroke his neck. ‘Hello there, old fellow,’ he murmured. ‘I’d guess you have some stories to tell.’

‘Best watch yourself, mister,’ the youth in the battered hat warned him. ‘He doesn’t take kindly to strangers.’

‘Doesn’t he, now?’ Jack tickled the animal behind one ear until it gave a soft whicker of pleasure.

The lad’s face was shadowed by that big hat, but Jack was pretty sure he looked irritated by the horse’s evident delight. The lad tugged at his horse’s leading rein and moved on, but called back over his shoulder, ‘Hear that noise? You won’t find those tar barrels quite as friendly as my horse.’

Indeed, there was an ominous rumbling sound getting louder and Jack spun round, jumping out of the way just in time to avoid being hit by some huge barrels that were being rolled along the quayside. Damn! That was close. Breathing rather hard, he took one last look at the grey horse and its slim owner both heading for the blacksmith’s forge, from which came the clanging of hammers on hot iron.

The noise and clamour reminded him that everyone around here was busy except for him and slowly he set off back to his shop, but he was sorry to leave the wharf with all its bustle and energy. More than once he’d found himself envying the sense of community these people who lived around the wharf seemed to enjoy, the sense of belonging. They were also a watchful set and it hadn’t taken long for the regulars to get to know where Jack lived—they called him Mr Percival, or sometimes just Mr Percy, the antiques man. Right now, a bunch of young women from the boats were walking back with full baskets from the local food market.

‘All right there, Mr Percy?’ one of them called. ‘D’you need a hand with anything today?’

They were casting eyes of approval over his curly black hair, his leather waistcoat and breeches and boots. He smiled back. ‘All right,’ he said. ‘I’m all right.’

But that wasn’t entirely true.

Letting himself into the dust and disarray of his shop, he lit a couple of candles to highlight the debris and wondered what on earth to do next. For several years he’d served with the British army in Spain—in fact, he’d been an officer and Lord Wellington himself had valued him highly. ‘You’re my man for tactics, Rutherford,’ Wellington used to say to him. ‘You’re my man for digging out the enemy’s secret plans.’

And what were Jack’s plans now? He was aiming to get back his inheritance, that was what. He was plotting revenge against the man who’d robbed him, while he’d been away, of his home, his heritage and his pride.

Who’d robbed him, in other words, of pretty much everything.

Chapter Two

‘There. That’s Hercules sorted for you, young Matty!’ The blacksmith checked the horse’s freshly shod hooves, then nodded his head in approval. ‘He’s a fine old fellow. Let me know if you’re thinking of selling him off, will you?’

The blacksmith’s forge, Matty always thought, was like a goblin’s cavern, glowing with the heat of the furnace and the glitter of molten metal. In answer to the blacksmith’s question, she shook her head. ‘I’ll not sell him, ever. He’s an old friend, and we won’t be parted.’ Carefully she counted out some coins into the blacksmith’s sooty palm and began to lead Hercules back to the wharf.

Of course, the blacksmith never suspected she was a girl. Nor had that man who’d nearly been felled by those rolling tar barrels a little earlier. She shook her head at the memory; he’d looked like some arrogant ne’er-do-well and he’d taken more notice of Hercules than he had of her. Like most people, he’d assumed Matty was just another local lad and she was fine with that. Yes, thank you very much—just fine.

As Hercules clopped along beside her, she stroked his neck. ‘Pleased with your new shoes, are you, old fellow?’

He nuzzled her neck in reply and she smiled as they walked on past the warehouses to the canal basin.

She had never deliberately set out to deceive people and her long coat and big hat weren’t intended as a disguise—it was just that she found men’s clothes more comfortable, more useful. She was nineteen years old and her full name was Matilda Grey. She’d lived on the canals all her life and as she walked by the moored boats, people stopped what they were doing to greet her. ‘Morning, young Matty! How’s Hercules? Did you get him sorted out at the forge?’

‘Hercules is fine,’ Matty called back. ‘He needed shoeing, of course. But the blacksmith said that now he should be ready for anything.’

Yes, all her canal friends knew she was a girl, but strangers didn’t realise, not unless they got up too close. And she didn’t normally let anybody get too close, no, indeed; she kept her chestnut-brown hair cropped short, she wore a shirt and trousers together with an old coat that reached past her knees and some strong leather boots—no dainty shoes for her. She found it so much easier to dress like that. It helped her to look confident and carefree.

Even though today she felt anything but, because the blacksmith’s fee had reminded her that she only had enough money left for three or maybe four more months of this way of life. This can’t go on, Matty. The bills came in regularly for berthing her boat as well as for Hercules’s stabling and food and that nagging little voice of worry had been wearing away at her for days now. Some day soon either her horse or her boat would have to go. Then what?

She looked around for inspiration, noting that as usual at this time of day the canal basin was packed with boats being laden with grain and timber for the journey north. ‘One boat drawn by a single horse can carry six times as much as a cart pulled by four horses,’ she remembered her father telling her when she was small. ‘Canals are the future, Matty!’

He had died two years ago and recollecting his voice rekindled her sense of loss, together with her fears. Yes, canals might well be the future—but perhaps not for her.

She realised a woman was calling out to her from one of the nearby boats. ‘How’s things, Matty, love? Getting ready for another trip, are you?’

Bess, one of her oldest friends, had a big soapy scrubbing brush in her hand. She was always scrubbing something—her boat, her laundry or her children. ‘I’m making plans, Bess,’ Matty replied. ‘You know?’

‘You and your plans!’ Bess shook her head and tutted, but in her eyes was nothing but kindness. ‘Just be sure to let me and my Daniel know if you need any help, won’t you?’

‘I will. My thanks, Bess.’ And Matty walked on towards her boat, The Wild Rose, where she tethered Hercules close by.

She’d been only three when her mother died and Bess in particular had taken Matty to her heart, cooking meals for her and her father, offering company when it was needed and easing the pain of loss for them both. Matty counted Bess and her husband among her most loyal friends, but Bess would still be watching her, she knew, and just now she needed some privacy. Making for the solitude of her tiny cabin, she dragged off her boots and sat down on the narrow bed.

She still missed her father, so much. An Oxford graduate, he had earned his living by writing articles for historical journals and occasionally giving lectures. He could have made a comfortable living as a tutor, but he loved the canals as much as he loved history—and Matty always suspected that, well educated though he was, he enjoyed the company of the canal folk as much as that of the Oxford men. There was nothing he relished more than to sit by the waterside with fellow travellers on a summer night listening to their tales and he looked after The Wild Rose as well as any true bargeman, seeing to the tarring and caulking, retouching the paint and polishing the brass work all by himself. From an early age Matty would follow him around, saying, ‘Let me help, Papa!’

‘We’ll do it together,’ he used to say.

Of course, the loss of his wife was a sharp grief, but he’d found a kind of peace, Matty always believed, in travelling with his young daughter from one town to another along the waterways. And everywhere they stopped, he would explore the surrounding countryside for old battle sites or castle ruins. Sometimes, her father unearthed valuable relics—though since the last thing he wanted was to make money out of them, he often gave his finds to museums or to other scholars to assist with their research. ‘Our treasure hunter,’ the canal folk liked to call him proudly.

From time to time Matty heard strangers whisper that it was a lonely and unnatural way of life for her father to inflict on his daughter, but in those days Matty was never lonely, for she had all of the canal community as her family. The women took special care of her and did what mothers do, explaining about growing up, giving her dark warnings about men—and oh, how they yelled at their own sons if they were too familiar with her! ‘Don’t you try anything with our Matty! She’s special, d’you hear?’

It was indeed a special life with her father on The Wild Rose. In the summer months he taught her all about the birds who lived by the canals, the flowers and the water creatures; while on winter nights, when often the water on the canals would freeze over, they’d sit snug in their cabin and he told her enthralling tales of times gone by. He taught her practical things, too, like how to look after the boat and navigate the locks or how to make sure she was never cheated by the innkeepers or blacksmiths. Matty had grown up both capable and knowledgeable—and it was just as well, because two years ago her father had suddenly died.

‘A heart attack,’ the doctor had told her gravely. ‘You mustn’t blame yourself in any way, my dear. There was clearly nothing you could do.’

Her friends had gathered round after the funeral and offered their advice. ‘Maybe now’s the time to give up the boat, Matty, and consider another life.’

They were anxious about her, she knew. ‘A girl her age, on her own in a boat,’ she’d heard them whisper. ‘It’s not right. Not safe.’ More than anything, it was becoming unaffordable—but what other kind of life could she possibly consider, after living so long with the freedom of the waterways?

For the last two years, she’d earned occasional money by carrying light loads on her boat for short distances only, taking on parcels of fabric or chinaware or other delicate goods. Hercules might be old, but he was also well trained—he knew exactly how to plod calmly along the towpath without starting at a flock of ducks or shying at an oncoming barge, while Matty, manning the tiller, dreamed of travelling farther some day and finding the lost treasure her father thought he was close to discovering only days before he died.