Полная версия

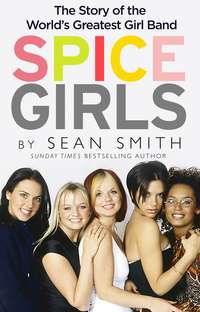

Spice Girls: The Story of the World’s Greatest Girl Band

More seriously, she went out for two years with another pupil, Ryan Wilson. He was her first love and she was his. Importantly, his mum Gail liked her: ‘Melanie was a charming girl – very feminine and very pretty.’ They used to walk home together – Ryan lived with his parents in a large five-bedroom house – and talk about their ambitions. Melanie’s plans seemed to revolve around dancing. He remembered, ‘She once said to me the hardest thing about life is deciding what you want. Getting it is easy.’

Intriguingly, her old schoolmates do not remember Melanie as a tomboy, kicking a ball around with the lads. Ryan recalled she was a quiet girl, the quietest of all the prefects. Another friend, Mark Devany, agreed it was rubbish that she was a tomboy: ‘She was always very girly and ballet mad,’ he said.

Blood Brothers was not the only school production Melanie was in, but she never secured the lead. In fact, for The Wiz, she had to make do with playing the part of one of the four crows. She was a girl who wanted fame and fortune away from the mean streets of a Cheshire town, scrawling ‘Melanie Chisholm Superstar’ on the cover of one of her school books.

Throughout her childhood and into her teenage years, Melanie won many dancing trophies. She kept her dancing world separate from school but two evenings a week and the whole of Saturday were set aside for classes. Originally she wanted to be a ballerina but realised as she got older that she was better suited to being one of the dancers on Top of the Pops, which, naturally, she watched every week.

Her dancing training helped with sport at school. She excelled at gymnastics and could execute a mean back flip, was better than average at netball and athletics but less good at football, even though she was a lifelong fan of Liverpool Football Club.

While she preferred to spend her pocket money on her Saturday dancing rather than on trips to Anfield she has never wavered in her support and would watch the games on telly on a Sunday afternoon with the rest of her family, who were also big fans. These were the glory days of the 1980s when Kenny Dalglish, Ian Rush and Graeme Souness would thrill the Kop. Her favourite player was goalkeeper Bruce Grobbelaar, who always had a great rapport with the home fans: ‘I loved it when he used to walk on his hands up and down the pitch.’ As an older teenager, she fancied Jamie Redknapp but he didn’t join the squad until she was seventeen and already on her way to college.

Melanie knew what she wanted at this point in her life – to leave school at sixteen and go to dance college. She passed nine GCSEs before she left, even though she was more interested in her next dance class than knuckling down to revision. She retained some affection for her old school and was reportedly disappointed when it closed in 2010 and was subsequently demolished to make way for a new housing estate and a cemetery.

She impressed at her audition at the Doreen Bird College of Performing Arts in Sidcup, Kent. This was another such school founded in the post-war years by a strong-minded woman, who became much admired in the dancing world. Melanie’s audition notes read, ‘Melanie has a nice appeal. She is strong with a flexible body. Her audition piece was very nice. She is very bright and has good potential. Should do well.’ When she applied, Melanie had to mention her ambitions in entertainment and wrote, ‘I want to play Rumpleteazer in the musical Cats – the part Bonnie Langford played – and to record.’

Melanie was still primarily a dancer. The school’s artistic director Sue Passmore observed, ‘She was a very strong, technical dancer. She was a hard-working and single-minded pupil.’ At this stage she still saw her future as a dancer and not as a singer. Her college musical director Pat Izen did not think her voice was that good when she arrived: ‘It was gutsy but she had an excellent ear – and she was a real individualist.’

Melanie’s breakthrough as a singer, at least as far as having her confidence boosted, occurred when she took part in a college revue and performed ‘Chief Cook and Bottle Washer’, a showstopper from the Broadway musical The Rink. She was delighted when the audience started whooping: ‘In that moment, I knew I wanted to sing.’ This was a song that demanded a ‘performance’. In the original production in 1984, the peerless musical-theatre star Chita Rivera gave it the full treatment and won a Tony award.

Melanie thrived at the Doreen Bird College. Sidcup was about as far as you could get from Widnes so it was brave of her mother to support her leaving home at sixteen to go down south. Melanie still had to deal with the dilemma all the future Spice Girls faced after leaving college of trying to get work in a crowded profession.

She signed on the dole and started the round of auditions. The closest she came to a breakthrough in 1993 was nearly being hired for the chorus of Cats in the West End, which might have set her off on a career in musical theatre. Instead, it was looking increasingly likely that she would end up taking work on a cruise ship. Fortunately, however, she picked up one of Chris Herbert’s flyers and decided to try out for his new girl group.

On the day, the dancing proved no problem and she sang the exuberant ‘I’m So Excited’ by the Pointer Sisters, a hit in the UK in late 1984. Chris was more impressed than his dad Bob, who for some reason didn’t rate her dancing but did think she was a much better singer than the other Melanie from Leeds. He wasn’t struck by the looks of either girl, giving them both four out of ten on their informal scoresheets.

Melanie hadn’t dressed up for the occasion, a simple cut-off lilac T-shirt and black trousers. Her hair was down and not in a ponytail. But, most importantly, she was just a little bit different from Victoria Adams and Melanie Brown – which worked to her advantage when Chris was back in the office making up his shortlist. He wanted contrast.

From that point of view, he noticed a younger teenager called Michelle Stephenson, who did well with a challenging ballad, ‘Don’t Be a Stranger’, then a recent top-ten hit for Dina Carroll. Michelle had only just turned seventeen so was appreciably the youngest of the probables.

Like Victoria, she was brought up in the Home Counties but was more traditionally middle class. Her father George worked for Chubb Security and her brother Simon was an artist and creative director. They lived in Abingdon, a lovely old market town on the Thames, just south of Oxford.

Unlike the others, however, she was much more involved in acting than any serious stage-school dancing. She had work with the Young Vic and the National Youth Theatre on her CV. She revealed, ‘I actually wanted to be an actress. I just went along for the audition because I had not been to an open audition before. I just went along for the experience.’

She already had a place to study theatre and English at Goldsmith’s College, part of the University of London, so a back-up plan was in place if the audition didn’t work out.

Michelle was invited to the first call-back at Nomis Studios. The building in Sinclair Road, Brook Green, had been turned into a studio complex in the late seventies by Simon Napier-Bell, who would later manage Wham!. Nomis is his first name spelt backwards. At any given time during its golden age, you might have caught Tina Turner, Queen, George Michael or the Rolling Stones enjoying bacon and eggs in the canteen there.

Chris and Bob began the recall by chatting to the girls individually, then dividing them into three groups. One group that seemed promising consisted of Melanie Brown, Victoria Adams-Wood, Michelle Stephenson and a Welsh girl from Cowbridge, near Cardiff, called Lianne Morgan. They were given three-quarters of an hour to devise a dance routine to another Eternal hit; this time Chris had chosen ‘Just a Step from Heaven’, which was in the charts at the time so at least everyone knew it. Not surprisingly, the irrepressible Melanie took the lead and the others were happy to follow her ideas.

Just when they thought they were ready, Chris and Bob threw a spanner in the works by telling them to bring another girl up to speed – Geri Halliwell. She was a riot of colour, wearing a pink jumper, purple hot pants and platform shoes, topped off with her vibrant dyed ginger hair that she had styled into pigtails. Melanie put it succinctly, ‘She looked like a mad, eccentric nutter from another planet.’ She certainly knew how to be the focus of attention in any room.

By the end of the afternoon this group of five were by far the most promising. They sent each girl away with a tape of ‘Signed, Sealed Delivered, I’m Yours’ by Stevie Wonder and asked them to return to Nomis in a week’s time to be put through their vocal paces to see how they blended together and whether they could harmonise. The media has found some of those disappointed that day but the one who came closest was Lianne. She was in and then she was out.

Chris and Bob had a rethink during the week and decided that Melanie Chisholm would better fit their concept for the girl group. Lianne was coming up to twenty-four while her replacement was twenty. She was hugely disappointed to receive a letter from Chris in which he said she was too old for what he had in mind and perhaps a solo career might suit her better.

Over the years Lianne has been quoted in various interviews commenting on what she saw as an injustice: ‘I’m a better singer than all of them,’ she maintained. That may well have been the case but singing ability was low on the list of priorities for the new band. She was older than Geri so the average age of the band dropped markedly without her.

Ability to sing or dance was completely irrelevant. In a later confidential memo, Bob Herbert was frank about how Heart Management viewed Geri: ‘We included her because she had a very strong personality and her looks seemed to suit the image we were trying to project. Unfortunately she was tone deaf and had awful timing, which meant she was unable to sing in tune or dance in time.’

6

A Model Girl

Typically, Geri was filled with enthusiasm and positive energy at the prospect of being in a girl band and wasted no time telling everyone she knew in Watford. They included a young researcher at the BBC called Matthew Bowers, who drank in the same bars and was keen to make an impression in television.

He was working on a documentary about Muhammad Ali called Rumble in the Jungle and mentioned to the film’s director, Neil Davies, that he had a friend who was auditioning for a girl band and asked him if he thought it might make something. Neil, an ex-paratrooper, immediately saw the possibilities and the two went to the next instalment of the search – the ‘Signed, Sealed, Delivered’ workshop day at Nomis.

Most importantly at this stage, Neil had to make sure Chris Herbert was onside. Fortunately the go-ahead young manager could see the advantages of a film. Neil was impressed: ‘I thought he’d had a brainwave in trying to form a sort of Backstreet Girls – everybody at the time thought you would never get another girl band going. It was all boy bands – Take That dominated the scene. So I thought, “This guy is a genius”. He’s twenty-one so I could see this was going to be a great story – even if they never made it. It would be a kind of warning to teenage girls that this is what happens to you in Tin Pan Alley.’

He shook hands with Chris and started filming that day. He needed to obtain the written consent of the girls but the more pressing thing for the five on the day was making a good impression with Heart Management. Bob Herbert was there and Chic Murphy had come to watch for the first time so that he could see for himself where his money was going. Neil amusingly described the two men as observing the ‘Marbella Dress Code’ – the top three buttons of the shirt undone and a big medallion hanging in the middle of the chest.

As well as being introduced to Chic, the girls had the chance to meet each other properly. In particular, they hadn’t noticed Melanie Chisholm at Danceworks and she had missed the next audition so this was an opportunity to chat to her. She obviously had no airs and graces and seemed to fit in easily.

All the girls thought they sounded terrible together – definitely a cat’s chorus. To their surprise, Chris, Bob and Chic seemed a little hard of hearing that day, although the purpose of the get-together was to see if they had a future, not how they sounded in the present. As Chris explained, ‘We wanted to create a band as a unit so it did not matter so much if, individually, they weren’t so strong.’ It went well enough for Chris to move on to the next stage.

He booked the five into a bed-and-breakfast in Knaphill, Woking, which was a few miles down the road from the Heart offices. Ostensibly the week was for them to rehearse, but that was only part the plan: ‘It was just for them to spend a little time together, and see whether they actually got on and started to bond. Initially we wanted to observe and see if there was something there or if we had to make changes.’

He introduced them to working together in a studio, picking them up from the B&B and dropping them off at Trinity Studios nearby. That sounded grander than it actually was. It was little more than a glorified village hall in urgent need of a lick of paint and a decent central-heating system. The building had once been a dance studio, so at least provided the space for the five girls to hone their dancing skills. Trinity was run day to day by Ian Lee, who remembered that first week: ‘They were like five schoolgirls – a bit giggly and a bit insecure.’

After a general discussion, it was decided that for the moment they would be called Touch, a pretty uninspiring name – sounding more like a group who would perform at Eurovision than one that would inspire a generation of female devotees. Chris was keen, though, for the group to have a five-letter name. More significantly, he began putting together a team who could help shape their future during this training period.

Once more the Three Degrees provided the link. He asked their former musical director, Erwin Keiles, to come up with a song or two to get the girls started. The first they had to learn was called ‘Take Me Away’, a mid-tempo unchallenging number. Chris brought in the gloriously named Pepi Lemer, a coach of considerable experience and a backing singer since the sixties, when she missed out on stardom.

Pepi realised that collectively the girls had a lot of work to do: ‘I remember them being quite attractive in their various ways but terribly nervous. They were shaking and, when they sang, their voices were wobbling. It has to be said that they weren’t very good.’ At the end of the week, Touch gave Chris, Bob and Chic an exclusive performance of that first song. They were dressed in a manner that would, in the future, never work for the Spice Girls – they were colour-coordinated in black and white. They were the Five Degrees.

It was all exciting, though. Apart from Michelle, this was a bunch of seasoned auditionees, thrilled that they were involved in something so new. Even the cosy, old-style guesthouse was stirred by their vitality. Victoria shared a room with Geri, who complained that she was taking up all the space with her two suitcases full of designer clothes. They clicked immediately. ‘You must come with me to a car-boot sale,’ said Geri – as if that was ever going to happen.

Victoria was the first of the five to give Chris some concern when he found out that she was already in a band called Persuasion. He told her that she needed to make a decision: ‘Are you in or are you out?’ Victoria was much cannier than people realised. She kept her options open just in case Touch came to nothing. She told Persuasion that she was going away on holiday for a week or two and would have to miss rehearsals.

Chris had to keep his fingers crossed where Victoria was concerned but another potential problem was building within the group. Four of the girls – Geri, Victoria and the two Melanies – were getting on famously but the fifth, Michelle, was becoming more distant. This was not the gelling unit Chris wanted: ‘Even when they broke for lunch or a coffee break, the four would be inside having a coffee and Michelle would be outside. She seemed a bit separated from the others. We spotted it and thought there was a problem developing even during that initial week.’

A bigger concern was their lack of progress at Trinity Studios. Clearly they needed much more time to practise and improve. Chic came up with the solution. He happened to have a spare three-bedroom house in Maidenhead. The girls could move in right away. It was basically a drab semi on a grey estate in Boyne Hill Road. Geri had clearly already had enough of sharing and bagged the tiny single room for herself. She was the oldest so there was no argument. Michelle and Victoria bounded up the stairs and managed to grab the twin-bedded room. That left Melanie Brown having to put up with Melanie Chisholm snoring away in one double room. Having two Melanies in the group was slightly problematic especially as they both preferred the longer version of the name. Chris began to call Melanie Brown ‘Mel B’ to help differentiate between the two.

Relations within Touch continued to slide throughout the first month. The gang of four were exasperated by what they perceived as Michelle’s lack of commitment. She wasn’t putting in the work to improve her dancing, preferring, they said, to top up her tan at lunchtimes rather than copy Geri’s lead and practise hard to try to catch up with the dance-school veterans. Perhaps, tellingly, Michelle still had every intention of going to university in the autumn. She also had a Saturday job in Harrods that she didn’t give up.

Melanie Brown, in particular, tried to motivate her but in the end the gang of four felt they had no choice other than to express their misgivings to Chris and Bob, echoing the thoughts the Herberts already had. Bob explained, ‘She would never have gelled so we had to let her go.’

Did Michelle go of her own accord? Was she pushed? Or was it a mutual decision? There were two sides to the story. While it was true that the other girls questioned her desire, Michelle, herself, was struggling with a family crisis – her mother Penny had been diagnosed with breast cancer. She was also the youngest of the group – five years younger than Geri. There’s a world of difference between just leaving school and hosting a game show on Turkish TV.

Michelle went travelling around Europe before starting her degree. She has had to live with the label of being the Spice Girl who wasn’t – although, at the time, Touch was nothing like the Spice Girls. She didn’t enjoy the music they were rehearsing, considering it far too poppy for her taste. She was not a fan of Take That, for instance, much preferring the harder edge of Oasis and the Prodigy. She later told Neil Davies that she became frustrated by the slowness of it all and she ‘didn’t think the girls would make it’. She added simply, ‘I had different plans for my future.’

Of the four who remained, Victoria was by far the rudest about Michelle, describing her voice as ‘cruise-ship operatic’, her dancing as ‘having less rhythm than a cement mixer’ and saying that she ‘couldn’t be arsed to improve’. The normally more outspoken Mel B described her as ‘sweet, very upper class and very well turned out’. In fact, Michelle was probably more posh than Victoria, although she didn’t have the wardrobe full of designer labels. Michelle remarked, ‘Victoria had some beautiful clothes.’

Michelle has made her own way in music. She has recorded her own songs, acted as a backing singer for Ricky Martin and Julio Iglesias and presented for Channel 4. She once said, ‘Of course I regret I’m not a multi-millionaire like them. But at the time I left the group I knew I was doing the right thing – and I still think it was the right thing.’

Eight years after she left, Chris and Shelley were in the Pitcher and Piano bar in Richmond when he recognised the waitress. It was Michelle. He recalled, ‘We shared a fond welcome and had a good chat.’ By that time, they both had cause for some regret. She would continue to be involved in music by hosting club nights before eventually marrying Hugh Gadsden, the manager of Madness.

Michelle’s departure created a vacancy. Chris and Bob didn’t go back to their original shortlist but decided to try to find someone new. They still wanted a five-piece band but they couldn’t face going through a drawn-out audition process again just to find one girl so they asked Pepi Lemer if she could think of anyone. She could – one of her former students, Abigail Kis, a half-Hungarian girl with a stunning, soulful voice.

She proved to be a non-starter. She had a steady boyfriend who, by all accounts, was not that keen on her moving into the house in Maidenhead. She also had a place at university to study performing arts, which seemed a better option for her. With hindsight, she was probably a fraction too young, and putting a boyfriend first was not in keeping with the ethos of the rest of the band. She became another ‘fifth’ Spice Girl, observing sadly, ‘I would have loved to be that famous. Every time I see them I think, “It could have been me.”’

While they searched for the right replacement, there was some good news for Chris when Victoria told him she had decided once and for all that her future lay with his all-girl band and not with Persuasion. She had talked things over with her parents and realised that everything was much more professional with the Herberts and she could not keep both going if she was going to continue living in Maidenhead. This was business and she seemed to have no compunction in ditching her former bandmates.

Nothing was etched in stone as far as the make-up of the new group was concerned. It seemed a good idea, however, that the fifth member should be the youngest – thereby lowering the average age of the five. It was back to the drawing board for Pepi, whose next thought was a bubbly blonde girl she had taught three years previously at Barnet College. She remembered that her name was Emma Bunton but, in those pre-Facebook days, had no idea how to contact her. She had to pop into the college to search through old records before eventually coming up with a phone number. Emma’s mother, Pauline Bunton, answered and Pepi explained that she wanted to invite her daughter to try out for a new girl group.

Emma was thrilled to be asked. She had the advantage of being another stage-school veteran and had attended many auditions. Chris drove over to North London to meet her and her mum, and they had a pleasant chat over a coffee before going back to Pepi’s house where Emma sang ‘Right Here’, a top-three hit in the UK the previous year for the all-girl American R&B trio SWV (Sisters with Voices). It was a good choice. Chris Herbert thought she was perfect: ‘She was very cute, very nice with a sweet voice, a very “pop” voice. I really liked her character a lot. It was one of those light-bulb moments when I realised she was definitely something we didn’t have. It was immediate for me.’

Chris had to explain, though, that it all depended on her being accepted by the other four. They would have to look at the dynamic between her and the current residents of the house in Maidenhead. One thing stood in her favour – that she was from a working-class background in North London. When Emma Lee Bunton was born in the Victoria Maternity Hospital, Barnet, on 23 January 1976, her father, Trevor, was a delivery driver. She would be the youngest of Touch but was actually older than Michelle.

Trevor subsequently became a milkman and sometimes took his daughter out on his rounds during the school holidays. Her mother did her bit for the family finances, working as a home help for a well-to-do local woman. Pauline was raised in Barnet but her father – Emma’s grandfather – was Irish, Séamus Davitt, from County Wexford. They were Catholic and Emma had a traditional baptism and attended mass growing up. Sadly, she never knew her grandfather, who died before she was born.

She has an older half-brother, Robert Bunton, from Trevor’s first marriage and she would go to the park and watch them play football in the local league at weekends. Her younger brother, Paul James, known as PJ, is four years her junior and the two of them are very close. They shared a room until Emma was twelve. Because money was tight they sometimes needed to share their dinner as well.