Полная версия

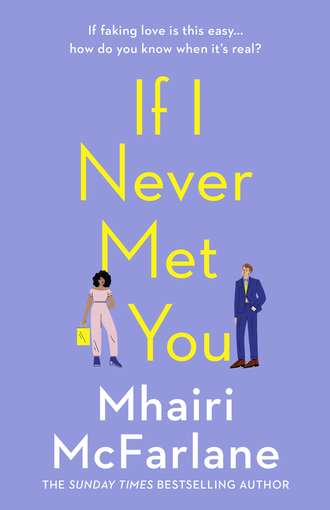

If I Never Met You

‘He always said marriage was a rotten institution, a place people went to die!’

‘Yeah. Well this is his journey, I guess. What his heart is telling him.’

Laurie was being sarcastic but it evidently didn’t register. She could hear her mum fidgeting on the other end of the phone, and pictured the frown that usually accompanied mentions of her father.

‘I shouldn’t be surprised at your father being a shit by now, and yet somehow I always am.’

‘He says they did it for tax breaks.’

‘Ever the romantic,’ she sniffed.

Of course, had Laurie said he’d done it for love, her mum would’ve scorned that too.

‘Please warn me when he’s having his reception because I do not want any chance of running into him and this woman. Wanda and I were going to come over for an exhibition at the Whitworth.’

‘Mum, I don’t mean to sound mean-spirited …’ Laurie knew she was about to start a fight, even while she intellectually, rationally, wanted a fight with her mum like she wanted a hole in the head. Yet emotionally, it was somehow an inevitability. ‘I tell you my boyfriend of eighteen years dumped me and it was, oh well Dan must have his reasons to follow his lodestar and I’ve told you Dad’s got married, and he left you thirty-seven years ago, and you’re now pissed off and angry. Why can’t I be pissed off and angry at Dan?’

‘You can! When did I say you couldn’t be?’

‘The whole “he must be doing the next part on his own and listening to his heart” stuff wasn’t exactly saying I had a right to be upset.’

‘Of course you do, but he’s not cheating on you, he’s not lied to you? What do you want me to say, Laurie? Do you want me to criticise him?’

‘No!’ She didn’t. Infuriatingly, she still felt defensive of him. ‘It’d just be nice if …’ she trailed off, as what came next was harsh.

‘What?’

‘… As if you sounded like you cared about my break-up anything like as much as you care about Dad’s rubbish.’

‘That’s a dreadful thing to say, I care much more about you than I do about him!’

Hmmm yeah, not what Laurie was saying, but how did Laurie think it would go, pointing out her mum’s hypocrisy in the sting of her dad’s news?

Her mother and father were opposite perils, Laurie realised: her dad said the right things and didn’t mean them and her mum might feel it, but she never said so.

They finished the call with terse politeness so they could go away and boil resentfully on the things the other had said.

As Laurie replaced the receiver she thought: well that was ironic, wasn’t that the ultimate moment to be bonding over similar experiences? You wouldn’t get this on the bloody Gilmore Girls.

Her mum was still heavily marked by what her dad did almost four decades ago; Laurie felt the tremor his name caused. Was that going to be Laurie’s fate where Dan was concerned, too?

At some point, you have to give up wishing for your parents to be who you wanted them to be and accept them as they are, Dan once said.

Easy for him to say, with his kind, dependable mum and dad who thought he was a prince among men and would drop anything and do anything for him.

As Laurie sat on the stairs, hugging her knees and nursing her bruised emotions, there was muttered cursing in the distance as someone tripped over a step, the scrape of a key in the lock, and Dan came in the door.

‘Hi,’ he said. He was pink from running, and wore the look of apprehensive guilt he always did around Laurie now.

‘Hi. I told my mum.’

‘Ah.’ Dan was obviously at a loss over what to say. ‘I’ve not told mine yet.’

Laurie had guessed that from the lack of call from Dan’s mum, Barbara. They got on very well and Barbara had always, in a benign way, treated Laurie as Dan’s PA and hotline to his psyche, as well as his diary. Yeah, good luck with that from now on.

‘I’ve found a flat,’ he said. ‘Quite central. I can move in next week.’ He gulped and rushed on. ‘I know this sounds really soon and that I’d had it lined up but I honestly didn’t. I was on Rightmove yesterday afternoon and it just came up and when I called the agent they said I could pop round this morning. It’s not great but it’ll do for now.’ He trailed off, his cheeks flushed with the exercise and – hopefully – mortification at being so evidently eager to see the back of her.

‘Oh. Good?’ Laurie said. She didn’t know what note to strike, in the teeth of total rejection. She’d always had this knack with Dan, she could joke him out of any temper, persuade him when no one else could. ‘He’s proper silly for you,’ a friend of his once said.

Now she felt as if anything she said would be either pathetic or annoying; she could hear it become one or the other to him as soon as it left her mouth. All the usual doors, her ways in, had been bricked up.

‘I’m going to keep paying the mortgage here for time being. Give you a grace period so you can decide … what you want to do.’

‘Thanks,’ Laurie said, flatly, because no way was she going to be more fulsome than that. Dan’s larger salary came with a ton of stress at times, but had its uses. She’d have to remortgage herself up to her eyeballs and eBay everything that wasn’t nailed to the floor. Losing Dan and her home felt insurmountable.

‘I’m going to get fish and chips for dinner tonight, want some?’ Dan added, and Laurie shook her head. The rest of the bottle of red in the kitchen would be more effective on an empty stomach. She noticed Dan’s appetite was fine.

‘When do we tell everyone at work?’ she said. They’d mutually avoided this pressing question yesterday, but Laurie knew her office mate, Bharat, would sniff it out in days.

They’d be a week-long scandal, with the news cycle moving into a different phase day by day. ‘Have you heard?’ on Monday, ‘Was he playing away?’ on Tuesday, ‘Was she playing away?’ on Wednesday, ‘I saw them arguing outside the Arndale last Christmas, the writing was on the wall’ fib dropped in as a lump of red meat to keep it going on Thursday. ‘When is it OK to ask either one on a date?’ nailed on by Friday, because Salter & Rowson was an absolute sin bin. There was a lot of adrenaline involved in their work at times, which was dampened by after hours booze. Add a steady influx of people aged twenty to forty joining or interning, and you had a recipe for a lot of flirting and more.

It was a shame this had happened now, just when the Jamie-Eve gossip could have been a useful distraction. But there was no way a furtive bunk-up, even a specifically verboten one, was going to trump the break-up of the firm’s most prominent couple. And Laurie wouldn’t have dobbed Jamie in either. She wasn’t ruthless.

Dan leaned on the wall and sighed. ‘Shall we not? For the time being? I can’t face all the bullshit. I can’t see how they’d find out otherwise. It’s not like I’m going to put it on Facebook and you’re hardly ever on there.’

‘Yeah. OK,’ Laurie said. They both wanted to wait for a time it’d matter less, though right now Laurie couldn’t imagine when that might be.

‘And my Dad’s got married.’

‘No way!’ Dan’s eyes lit up. He officially disapproved of Laurie’s dad in order to stay on the right side of history – and of Laurie and her mum – but she’d always sensed Dan had a soft spot. ‘To, what was her name, Nicola?’

‘Yeah. Some party happening here. I’m a bridesmaid.’

Barely true, but she wanted Dan to picture her in a dress, in a spotlight, in a glamorous context with scallywag dad, whom he sneakingly admired.

‘Ah. Nice.’ Dan looked briefly sad and ashamed as obviously, he’d not be there. ‘Never thought your dad would settle down.’

‘People surprise you,’ Laurie shrugged, and Dan looked awkward and then blank at this, muttering he needed a shower.

As Dan passed her on the stairs and his bathroom-puttering noises started, Laurie leaned her head against the bannisters, too spent to imagine moving for the moment. When they passed thirty, as far as their peer group were concerned, Dan and Laurie tying the knot was a done deal. If they weren’t thinking about it themselves, they weren’t allowed to forget it.

From acquaintances who’d drunkenly exhort, ‘You next! You next!’ at one of the scores of weddings they attended a year, to the open pleas from Dan’s mum to give her an excuse to go to Cardiff for a day of outfit shopping (the best reason for lifetime commitment: a mint lace Phase Eight shift dress and pheasant feather fascinator), to friends who told them, once they’d seen off bottles of wine over dinner, that Dan and Laurie would have the best wedding ever, come on come ON do it, you selfish sods.

Laurie always deflected with a joke about her not being keen what with being a lawyer, and seeing a lot of divorce paperwork, but eventually that dodge wore thin. Dan referred to Laurie as ‘the missus’ and ‘the wife’, leading newer friends to think they were married.

It had always seemed a case of when, not if. Laurie had vaguely expected a ring box to appear, but it never did: should she have been pushing the issue?

The where’s the wedding??!!! noise hit a peak around thirty-three. Having skirted around it, after news of another friend’s engagement, they discussed it directly over hangover cure fried egg sandwiches of a Saturday morning.

‘Do you not think it’s much more romantic to not be married?’ Dan said. ‘If you’re together when there’s no practical ties, it’s really real.’ He was indistinct through a mouthful of Hovis. ‘Realer than when you’ve locked yourself into a governmental contract. We of all people know that legal stuff means nowt in terms of how much you love each other.’

Laurie made a sceptical face.

‘We have no “ties” … except the joint mortgage, every stick of the furniture, and the car?’

‘I’m saying, married people stay when it’s rough because they made this solemn promise in front of everyone they know, and they don’t want to feel stupid, and divorce is a big deal. A big, expensive, arduous deal. As you say, you end up having the wagon wheel coffee table arguments over stuff for the sake of it, like in When Harry Met Sally. There’s the social shame and failure factor. People like us stay together when it’s rough out of pure love. Our commitment doesn’t need no vicar, baby.’

With his scruffy hair, sweet expression and expensive striped T-shirt, Dan looked the very advertiser’s image of the twenty-first century Guy You Settle Down With. Laurie grinned back.

‘So … what you’re saying is, there will be no weddings for you, Dan Price? Or, by extension, me? The Price-Watkinsons will never be. The Pratkinsons.’

He wiped his mouth with a piece of kitchen towel. ‘Ugh we’d never double barrel no matter what, right?’

Laurie mock wailed. ‘No huge dress for me!’

‘I dunno. Never say never? But not a priority right now?’

Laurie thought on it. She sensed it was there for her if she demanded it. She was neither wedding wild nor wedding averse. They’d been together since they were eighteen, they’d never needed a rush in them. Plus, it’d be nice not to have to find fifteen grand down the back of the sofa, there was plenty needing doing in the house. She smiled, shrugged, nodded.

‘Yeah, see how it goes.’

Emily always told Dan he was lucky to have such an easygoing, un-nagging girlfriend and Dan would roll his eyes and say: ‘You should see her with the pencil dobber in IKEA,’ but at that moment Laurie felt Emily’s praise was justified and she thought, looking at his warm that’s my girl smile, so did Dan.

And it was only now, listening to the shower thundering upstairs, that Laurie realised that she’d missed the giant glaring warning sign in what Dan had said.

Yes, staying together out of love, not paperwork, was romantic. But if you flipped it round, he was also saying marrying made it too difficult to leave.

Three days later, Laurie got a packet of seedlings for colourful hollyhocks in a card with a Renoir painting, and her mum’s unusual sloping script inside, read: ‘To new beginnings. Love, Mum.’ Laurie cried: this meant her mum had fretted on their conversation, it was her way of making amends. Maybe her mum hadn’t trashed Dan, had been upbeat on purpose – to make it clear this wasn’t history repeating, that Dan wasn’t her father and Laurie wouldn’t go through what she did.

Laurie had no faith anymore. As a lifelong believer in The One, in monogamous fidelity to the person who your heart told you was right for you, she was suddenly an atheist. If Dan wasn’t to be trusted, who could be?

In the years ahead, she knew plenty of people would tell her to be open to commitment again, to true love: that fresh starts were possible and it would be different this time. She knew she would smile and nod, and not agree with a word of it.

7

Two months and two weeks later

‘Can I come round?’

Laurie answered Dan’s call while she was walking to the tram after work, as Manchester’s late autumn, early winter temperature felt like it was stripping the skin from her face. She loved her city, but it wasn’t so hospitable in November.

It had not been an easy time. Ten weeks since the split, and Laurie felt almost as distraught as she did the day Dan left. Whenever their paths crossed at work, they had to chat vaguely normally so as not to arouse suspicion, because no one had figured it out yet. And as Laurie couldn’t bear the idea of their relationship being picked apart, she hadn’t done anything about it. It wasn’t a sensible thing to be doing, as grown-ups, not now they were living apart: they needed to face it. They’d also managed to keep it a secret from the rest of their Chorlton friendship group by pleading prior commitments to a few events, or in a couple of cases, attending singularly and lying through their teeth. But she couldn’t – wouldn’t – be the one to break the deadlock, as she hoped against hope they’d simply never need to tell everyone about this blip. She hoped the fact Dan didn’t want it known was a sign.

Laurie was no closer to understanding what the hell had happened. What did she do wrong? She couldn’t stop asking that.

Tracing the steps by which Dan fell out of love with her was excruciating and yet she guessed she had to do it, or be fated to repeat it.

Her only conclusion was that a distance must have developed between them, so slowly as to be imperceptible, so small as to be overlooked. And it had gradually lengthened.

Of course, the one person she had told, next to her mum, was Emily, ten days after the fact, who’d unexpectedly burst into tears for her. They’d been sitting in a cheapo basement dim sum bar under harsh strip lighting, a place that was usually quiet midweek. Laurie had asked for a table right at the back so she could heave and whimper without too many curious looks.

After hearing the details of Emily’s most recent work trip, a jaunt to Miami for a tooth-whitening brand with soulless corporate wonks, Laurie steeled herself and cleared her throat.

‘Em, I have something to tell you.’

Emily’s gaze snapped up from raking over the noodles section. Her hand immediately shot out and grabbed Laurie’s wrist tightly. Then her eyes moved to Laurie’s wine and her expression was more quizzical.

‘Oh God! Not that,’ Laurie said. ‘Nope. I’m safe to drink.’

She took a deep breath. ‘Dan and I have split up. He’s left me. Not really sure why.’

Emily didn’t react. She almost shrugged, and did a small double-take. ‘You’re kidding? This is a wind-up. Why would you do that?’

‘No. One hundred per cent true. It’s over. We’re over.’

‘What? You’re serious?’

‘I’m serious. Over. I am single.’

Laurie was trying that phrase out. It sounded a crazy reach, while being hard fact.

‘He’s finished with you?’

‘Yes. He has finished with me. We are separated.’

Laurie noticed that someone ‘finishing’ with someone else was such savage language. They cancelled you. You are over. Your use has been exhausted.

‘Laurie, are you being serious? Not a break? You’ve split up?’

‘Yes.’

Laurie was holding it together better than she expected. Then Emily’s eyes filled up and Laurie said, ‘oh God, don’t cry,’ her voice cracking, as beige lines streaked rivers through Emily’s foundation.

‘Sorry, sorry,’ Emily gasped, ‘I— can’t believe it. It can’t be real? He’s having a moment or something.’

That immediate understanding from her closest friend had been the straw to break the stoic camel’s back, and Laurie and Emily had wept together until the waitress slapped two large glasses of wine down on their table, muttering, ‘On the house,’ before hastily beating a retreat. Here’s to sisterhood.

‘Why? Has he had some sort of stroke?’ Emily said, when she got her breath back.

Laurie put both palms up in a ‘fuck knows’ gesture and felt what a comfort her best friend was. She’d been there from the start, since Laurie and Dan’s Fresher’s Week meet-cute. She was completely invested; Laurie didn’t have to explain the preceding eight seasons for her to be blown away at the finale. Finale, or mid-season hiatus?

‘He says he doesn’t feel it, us, anymore. The night we’d been out in The Refuge, afterwards he was waiting up for me, and it came out. He’d been thinking about leaving for a while. Which you know, is fantastic to hear.’ She paused. ‘We’d been talking about coming off the pill.’

Emily winced.

‘Ohhhh so it’s fear of fatherhood? Growing up, responsibility?’

‘I asked that, and also said that we could rethink having kids, but no. He’s decided our life makes him feel like he’s on a fast track to death and has to go rediscover himself.’

‘Could it be a trial separation? Putting you two on pause, while he twats about off the grid in Goa, like he’s Jason Bourne? God, whenever I forget why I hate men, one of them reminds me.’

Laurie laughed hollowly.

‘Nope, I doubt it.’ She couldn’t admit to any lingering hope she felt, it was too tragic. Other parties needed to fully accept it, on her behalf. ‘He’s found a flat. We’re going to work out the money in the next few weeks. Then that’s us done, I guess. He’s offered to trade the car for furniture so there will be no wagon wheel coffee table haggling.’ Laurie’s throat seized up again.

‘I don’t know what to say, Loz. He loves you to bits, I know he does. He worships the ground you walk on, he always has done. This is madness. This is an episode.’

Laurie nodded. ‘Yeah. It doesn’t make sense. The Didn’t See It Coming, At All, factor is fucking with my head really badly.’ She lapsed into silence to staunch the tears.

‘Well, tonight just got even drunker,’ Emily said eventually, catching the waitress’s eye to signal another round.

In the end they’d finished the night in an even grottier bar down the street, two bottles of wine down and one heavy tip for the poor waitress who’d had to clear up their snotty tissues. The memory of the morning after still made Laurie wince today. Anyone who moaned about hangovers in their twenties should be forced to suffer a hangover from your late thirties.

The worst of it was, after the fireworks of Dan’s declaration that he was leaving and that first shock of grief, the awful banality of ‘getting on with it’ was its own horror.

‘Never mind the fact I’ll be expected to do monkey sex in swings, like they have in Nine Inch Nails songs, who will I text boring couple stuff to, ever again? Like what shall we have for tea, pre-pay day? Who will I ask if they want “baked potatoes and picky bits” on a cheap Monday?’ Laurie had demanded of Emily. (‘Lots of people like baked potatoes!’ she had promised.)

It was the end of another night of boozy mourning, and as they waited on the corner for their Ubers to appear, Emily had nudged Laurie (probably slightly harder than intended).

‘Laurie, you know you’re going to get the Sad Dads sliding into your DMs any day now.’

Laurie barked a laugh. ‘Doubt it. Don’t assume that how men are with you, is how they are with me.’

‘Seriously, they’re shameless. Absolutely no idea of respectful pause, straight in there: hey I hear you’re back on the market, allow me to place the initial bid. I’ve heard this lament from the girls at work so many times. They all think they’re catches and they’re often still with their wives. They think you’ll be desperately grateful for any cheer up cock they can offer.’ Emily cupped her hands into a bowl shape: ‘Please, sir, can I have some more?’

When they’d finished sniggering, Laurie had said, ‘I don’t get that sort of attention. The attention you do.’

She felt so wholly unprepared to be back out there. As Emily pointed out, she’d never really been there.

‘Because a huge part of getting that sort of attention is signalling you’re up for that sort of attention.’

‘Hah. I can’t even think about it. I can’t imagine ever being any good for anyone ever again. I think Dan’s ruined me.’

‘OK, but don’t rule out the healing power of a purely physical fling. Sometimes, you don’t need face-holding I Love You intense meaningful sex. What you need is some hench dipshit with superior body strength to pin your wrists above your head and pound you with a virile meanness.’

Laurie groaned while Emily grinned triumphantly.

‘Did you briefly forget your pain?’

‘Absolutely,’ Laurie said, leaning her head on Emily’s tiny shoulder. She had the proportions of a malnourished Hardy heroine on a windswept moor. She was definitely a heroine though, never a victim.

This call from Dan was officially the first time he’d reached out to her to ‘talk’ in ten weeks though. Could it be … could he be …? No, squelch that thought.

‘Yeah. What, to pick stuff up? You still have your key?’ she said to Dan, hedging her bets, though she knew ‘picking up some stuff’ was a text, not a phone call.

‘No, I’m coming round to see you.’

‘What for?’

‘I need to talk to you.’

Laurie breathed in and breathed out. Right. She’d known this would happen. Almost from the first moment Dan had said he was going. Yet it coming true so soon still took her aback.

‘What about?’

‘I think it’s best said face to face. Is seven alright?’

Laurie’s heartbeat sped up, because she could hear the strain behind the casual delivery. Dan was scared. She felt oddly scared herself. What did she have to be frightened about? It was for her to weigh her answer.

She already knew what her answer would be. So did he.

They would have to creak through the formalities of his grovelling apologies, his prepared explanations for how he could’ve got it so catastrophically wrong, his vigorous heartfelt promises that he’d never mess her around again. The pledge to live in the dog house at first, to do better, to try harder. (That’s a point, there’d never be a better time to get that Lurcher she’d unsuccessfully campaigned for.) Tentatively working out how penitent he was prepared to be – did they raise the issue of Laurie being on or off the pill? Did Laurie want to proceed directly to parenthood with a man who’d left her on her own, while he worked through his fear of death in a sterile semi-furnished place near Whitworth Street?

No, absolutely not. He could move back into the spare room and they could take it slowly. Laurie was still in love with Dan but she was also realistic enough to know they would have a different relationship after this. It was a large wound. It had left her unable to trust him. It would take years to recover, fully. It would take years before, if he said they needed to talk, she wouldn’t be expecting rejection and a mad flit again.

She got in and put the lights on, tried to figure out what outfit she could change into that would make her look attractive enough to suit her dignity but not like she’d dressed up for him. In the end she went for jeans and a hip-length jersey top she’d not worn in a while that showed off her more prominent collarbones, and a dark shade of lipstick, from a worn down nub of an Estée Lauder matte long-lasting she rummaged for in the bathroom cupboards. Then she rubbed it off with loo roll and grimaced at herself. She wasn’t going to look like she’d been yearning and praying for this moment, even if she had been.