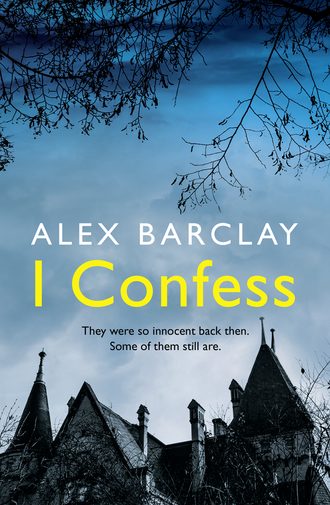

Полная версия

I Confess

‘All he does is sit in the house and read about history now,’ said Edie. ‘But he drinks a lot, so Mummy doesn’t like that.’

Her father’s gaze drifted out over the water. ‘But he’s a heartbroken man, isn’t he?’ he said. ‘Lost his wife, lost his job.’ He let out a breath. ‘We’d give the man a pass for that, surely.’

It was the first time her father had crossed the united front he and her mother usually presented.

‘Oh, Mummy does like Clare,’ said Edie, ‘but I think that’s only because she’s rich too.’

Her father leaned back from Edie a fraction and that one small move made Edie’s stomach flip and the blood rush to her cheeks. She had never felt ashamed in his presence before.

‘I’m sure your mother and I have both failed you along the way,’ said her father, skipping past it, ‘and I’m sorry that we did. But my advice to you is this – think of the past as a great big sea. It has delicious things we can feast on, a pearl here or there if we’re lucky. There are other things that are best left there, though. And conditions are not always favourable – unseen currents, waves waiting to crash. It’s best to take a quick dip, never wallow there, and certainly don’t drown.’ And he had smiled.

Her father was a prescient man. Edie still dived into that childhood sea, and fed on those creatures until she was sick. She had wallowed in the waters, crying into them, stirring up waves. There had been times when she hoped they would drown her.

Edie looked up at the walls of the inn. The rain on the granite had always looked to her like an oily film that could fall away from it in a single sheet. She had woken that morning, heaving and sweating, having dreamt that it had, and that she had watched, helpless, as it slid to the ground and rippled across the gravel towards her, and that she had stood, rooted, as it wrapped around her like a cocoon, and that she hadn’t made a sound, even when it started to tighten around her neck. When she woke, she felt that she hadn’t shaken it – not that she was bound by it, but that it hung over her like a threat. Daddy, what was I thinking?

Tonight, she and Johnny would be welcoming five of her closest childhood friends – Murph and Helen and Clare and Laura and Patrick. She waited for the joy to fill her heart. Instead, a thought came in to sink it: Five friends. No sixth – no Jessie.

All she could think of then was: I am the Ghost of the Manor.

3

EDIE

The Sisters of Good Grace Convent, Pilgrim Point

31 October 1988

Murph, Helen, Edie, Laura, and Clare were gathered at midnight by the chapel gate.

‘Happy Hallowe’en!’ said Murph.

‘Where’s your mask?’ said Clare. ‘You were the one obsessed with us wearing masks.’

‘The elastic broke,’ said Murph.

‘The size of the head on him,’ said Laura. ‘As if they wouldn’t know you if they looked out. Consolata up there closing her curtains: “Surely, that’s not that six-foot-four Liam Murphy goon running across my lawn. If only I could see behind that tiny plastic circle on his face – then I’d definitely know.”

‘Have you seen the selection down in the shop?’ said Murph.

‘I think we have,’ said Clare, looking around. They were all holding green Frankenstein masks.

‘Monsters, the lot of us,’ said Murph. ‘Is there no sign of Jessie?’

‘I wouldn’t hold out much hope,’ said Laura. ‘She was down town earlier, pasted.’

‘Oh, no,’ said Helen. ‘On her own?’

Laura nodded. ‘Apparently, Consolata was at her again, the silly bitch.’

‘All the more reason for her to come,’ said Murph.

‘I told Jessie I’d meet her,’ said Helen. ‘I don’t know why she couldn’t have walked up with the rest of us.’

‘Leave her off,’ said Laura.

‘She needs to ease up a bit,’ said Helen.

Murph nodded. ‘She needs to get a grip … on these.’ He held up a bag of cans.

They all laughed, but Edie knew they were all thinking the same thing – Jessie shouldn’t be drinking, not as much as she did, not on her own, not at sixteen, not after everything she had been through.

Murph looked up the road. ‘Here she is now. A dog to a bone.’

‘Oh God,’ said Clare, turning to Laura. ‘You were right.’

Jessie waved with a can of cider as she swayed towards them, a white plastic Hallowe’en mask pushed up on top of her head.

‘She shouldn’t be climbing a wall in that state,’ said Helen.

‘Laura can heave her up one side,’ said Murph, ‘and I’ll catch her on the other.’

They all put their masks on.

‘Frankenfuckinglosers,’ said Jessie, spreading her arms wide. She pulled her mask down. ‘Boo!’ She stopped like a soldier in front of them. ‘But what’s even scarier is I’m out of cider.’

They climbed over the stone wall, and ran alongside it, then slipped through the trees, and came out by three flat-roofed buildings that were derelict now, but were once part of the industrial school run by the nuns in the sixties and seventies. Murph stopped at the long, narrow dormitory block, crouched down by the door, and pulled out a key from under a rock next to it. He stood up and flashed a smile at the others, then unlocked the door. They followed him into the pitch-black hallway. Clare closed the door behind her.

‘Ladies,’ said Murph, turning on a torch, ‘this way.’ He kept the beam low as he shone it on the door to the left. He pushed it open, then stood with one foot over the threshold. ‘The living quarters of whoever had to prowl the dorm at night,’ he said.

They others took a look inside. It was a make-shift storage room now, with a timber countertop that ran along three walls and was covered with broken electrical equipment, cardboard boxes, crates of empty bottles, containers, and paint cans. There were more stored under the counter, along with rolled-up carpets and paint-spattered sheets.

‘Now,’ said Murph, ‘can I ask you all to adjourn to the hallway for five minutes?’ He looked at them solemnly. ‘I need to prepare the room.’

When they came back in, there was a picnic blanket spread out on the concrete floor, with church candles on two sides, and three more on the counter above. Everybody sat down.

‘Right,’ said Murph. ‘Gather round.’

‘Story time!’ said Jessie, leaning sideways, steadying herself with her hand.

‘Take the candle away from her,’ said Laura.

‘I’m fine,’ said Jessie. ‘Relax.’

Murph pulled it towards him when Jessie wasn’t looking.

‘Right,’ he said, leaning in. He lowered his voice. ‘It was a bright sunny day—’

‘I thought this was a ghost story,’ said Laura.

‘I’m going for “contrast”,’ said Murph.

‘And bad things still happen on sunny days,’ said Jessie. She knocked back a mouthful of cider.

Everyone exchanged glances.

‘Relax,’ said Jessie, lowering her can. ‘I’m just wrecking you. You can hardly never mention sunny days again for the rest of your lives because of me!’

Murph let out a breath. ‘OK … I’m going traditional: it was a wild night in Beara – raging storm, high seas, trees toppling, roads cut off. Five girls: HELEN, CLARE, EDIE, JESSIE, AND LAURA—’

‘Noo!’ said Edie. ‘Not our real names! You’ll jinx us.’

Laura rolled her eyes. ‘Fuck’s sake.’

‘Leave her alone,’ said Helen.

‘And I want to star in this, if you don’t mind,’ said Clare.

‘Me too!’ said Jessie.

‘Fine, then,’ said Edie.

‘Five girls,’ said Murph. ‘HELEN, CLARE, JESSIE, LAURA, and BABY EDIE … were driving out of town when, right in front of them, a towering oak fell from the skies and landed inches from their car. Laura tried to reverse, but behind them the hedge over the ditch split wide open and a river of mud and branches and stones poured through it, filling the road. The girls were trapped! What were they going to do? They were exhausted and so far from home. Then lightning struck, and pointed, like the needle of a compass, to … Rathbrook Manor – no more than a mile from where they sat.

‘“Why don’t we stay there for the night?” said Laura. “There may be a boy inside that I haven’t kissed yet!”

‘“Nonsense!” said Clare. “There’s not a single boy in Beara that girl hasn’t kissed!”

‘“Yes – let’s stay at the manor!” said Jessie, cracking open her fifth can of cider, looking up at the spires of the manor, which were a total blur, and, in fact, a tree.

‘“No!” screamed Edie, screaming hysterically. “I’ll scream if you make me stay there!” she screamed. Hysterically.

‘“Don’t tell me you believe in the Ghost of the Manor!” said Laura.

‘“Of course I don’t believe in ghosts!” said Edie. ‘It’s just … I have nothing with me! How can I possibly wear the same outfit two days in a row?”

‘The girls agreed that the manor was NOT haunted and so they decided to stay there, and they set off to walk the mile to the door. When they arrived, the manor was all locked up and in total darkness. Edie screamed. Laura punched her in the face and they walked on through the grounds until they stumbled across a dormitory. They peered in the window and saw row after row of iron beds, all of them empty. As they approached the door, it creaked open, and they all walked in. They each took a bed, side by side, and after hours talking about some ride they knew called Murph, they finally drifted off to sleep.

‘In the middle of the night, Laura woke with a start to find herself staring silently at a ghost standing three feet from the end of her bed. Beside her, Helen woke with a start to find herself staring silently at a ghost that stood three feet from the end of her bed. The same happened to Clare, and then to Jessie. The last bed in the line was Edie’s. When she woke to find a ghost standing three feet from the end of her bed, she was instantly hysterical, and she screamed at the ghost: “Who are you?”

‘And the ghost replied: “I am the Ghost of the Manor. And I am yours.”

‘Edie turned slowly to her left, and realized that each friend had a different ghost at the end of her bed.

‘As each girl stared at the ghost before her, all five ghosts stepped forward into the silvery moonlight that slanted across the ends of the beds like the blade of a knife. Each ghost had died a different way: Laura’s was bruised and broken, its eyeballs dangling from their sockets; Helen’s was covered in tyre tracks, its limbs at odd angles; Clare’s had half its head missing; Jessie’s was pristine; and Edie’s was covered in burns.

‘The friends’ mouths opened wider than a mouth naturally should, and their screams emerged as though ripped by the claws of a bear from the centre of their soul. But the source of their terror was not simply the apparitions that stood before them, nor the horror of their wounds. It was because each girl’s ghost looked exactly like her, just … older – maybe ten years, maybe thirty, maybe fifty. But the likeness was unmistakable!

‘Across this group of friends rippled the same realization: they had been RIGHT: the manor was NOT haunted. And this would be proven when, after they left, wherever they went, their ghost would reappear … some would say “without warning”. But, of course, each ghost DID carry a warning, a GRAVE warning. For it was not the Ghost of the MANOR. It was the Ghost … of the … MANNER … of DEATH.

‘And on that first night, as the friends were faced with the terrifying spectacle of the death that would befall them at some point thereafter, they were all struck by one thing: EDIE’S ghost, despite the burns that marked it, looked … the YOUNGEST.’

Everyone gasped, then gasped again as smoke started to rise around Murph.

Edie pointed. ‘Oh my God – smoke!’

Murph was unperturbed. ‘What?’

‘I’m serious!’ said Edie. ‘There’s actual smoke!’

‘Where?’ said Murph.

‘All around you!’ said Edie.

‘There is!’ said Laura.

Murph turned and looked. ‘Oh Jesus, lads. I was warned! If you tell this story on Hallowe’en night, it’ll come true.’

‘What?’ said Edie, getting to her feet. ‘Why did you tell it? What do you mean, it’ll come true?’

‘Unless,’ said Murph, ‘we all say “Sister Cuntsolata” three times backwards.’

Everyone looked at him.

Murph burst out laughing. ‘It’s a smoke bomb. Special effects, lads. Special effects.’

‘You prick!’ said Laura. ‘Where did you get your hands on a smoke bomb?’

‘I made it!’ said Murph. ‘A bit of this, a bit of that.’

Jessie reached into Laura’s bag for another can. She turned to Murph. ‘Can I still say Sister Cuntsolata three times?’

‘You can, of course,’ said Murph. A rush of white smoke appeared behind him.

‘Right!’ said Clare. ‘Open the door, someone. I’ve seen my cousins with these – there’s a reason you’re only meant to use them outside.’

‘Jesus – I know,’ said Murph. ‘Relax. It was only for a minute. Then I was going to fuck it out across the grass. I even have my protective glove lined up.’

‘So you want to draw the nuns on us?’ said Laura. ‘Throwing it out across the grass? No fucking way.’

‘To create a distraction,’ said Murph.

Edie started to cough.

‘The drama,’ said Murph.

‘Can you just put the fucking thing out?’ said Laura.

‘It’s not on fire,’ said Murph. ‘It’s fine. It’s safe.’

‘I’m happy here with my cans,’ said Jessie, closing her eyes, smiling.

Helen and Laura exchanged glances. ‘Locked,’ Helen mouthed.

‘Probably better off,’ said Laura.

Murph was starting to disappear into a cloud of smoke. ‘Okaaay,’ he said, standing up. ‘Maybe open the door.’

‘Why are there flames, then?’ said Jessie, looking up at everyone.

‘What?’ said Edie, panicked.

‘If it’s not on fire,’ said Jessie. ‘Murph said it wasn’t on fire.’

‘I can’t see any flames,’ said Clare.

‘There really are flames,’ said Jessie. She pointed into the corner. ‘Are those not flames?’

Murph rolled his eyes, but then he turned around. ‘Oh shit.’

Edie ran for the door.

Murph pointed to the corner. ‘Laura! Throw me that sheet, and that brush.’

Laura grabbed them and flung them at him. He threw the sheet on to the flames and used the handle of the brush to poke at it. The smoke bomb was still smoking.

Edie cried out from the door. ‘OK – this isn’t funny! Murph!’

‘What’s wrong with you now?’ he said.

Edie was holding up the doorknob.

‘What’s that?’ said Murph. ‘Did that come off? I didn’t do that. I swear to God!’

Murph’s eyes were so filled with fear that Edie started to cry. ‘Oh, God! No! No! No!’ She turned to the door and started slapping her hands against it. ‘Help us! Help! Help! Help!’

‘Shut the fuck up!’ said Laura, lunging for her. ‘For fuck’s sake. We’re going to get caught! We’ll be fucked!’

‘We’re surely fucked if we can’t get out,’ said Murph, striding past Laura to the door. Clare and Helen followed.

‘Seriously – how are we supposed to get out?’ said Edie.

Behind them, Jessie stood up, swaying, holding her drink high, trying not to spill it.

Laura was pointing to the hole where the doorknob should have been. ‘Can you not just turn the thing inside it?’

‘You can’t,’ said Murph. ‘You have to slide something in between the door and the frame to knock the latch back.’

Edie was sobbing.

‘Shut up,’ said Laura. ‘It’s not like we’re not going to get out.’

‘And I don’t think that sheet worked,’ said Jessie.

The others turned around, and saw the flames crawling along it.

‘Jessie! Get up, for God’s sake!’ said Clare.

‘Get over here!’ said Laura.

‘Will I throw some cider on it?’ said Jessie.

‘No!’ said Laura. ‘Get the fuck away from it!’

‘Don’t throw anything on it except water,’ said Clare.

‘Lads – what’s in those bottles under the counter?’ said Laura. ‘Could any of them be water? Those ones look like camping bottles.’

Jessie bent, put down her can, and picked up a bottle.

‘No, no, no!’ said Clare. ‘Don’t let her near anything! Don’t!’

Jessie started unscrewing the lid. ‘I’m only smelling it.’ She put it too close to her mouth, and tipped some on to her lips. ‘Oh, God no,’ she said, recoiling. ‘That’s kerosene.’ She swung the bottle wide, and everyone watched, horrified, as it sent an arc of fuel across the room.

‘Nooo!’ said Edie, hammering on the door, screaming for help.

‘Get her, Murph!’ shouted Helen, pointing at Jessie.

Flames were starting to rise. Murph reached a hand towards Jessie. ‘Get the fuck over here now.’

‘I’m coming, I’m coming,’ said Jessie. ‘Relax.’ But she took a step sideways, leaned too far, and then staggered back to the other counter.

‘OK – don’t move,’ said Murph. ‘You’re OK, there’s no fire there, but as soon as I get this fucking door open, head for Laura – her jacket’s nice and white, grab the back of it, and go.’

Edie and Laura were slamming their hands against the door, screaming for help. Murph pushed in behind them and hammered at the door with the side of his fist.

They heard a shout from outside, ‘Hello? Hello?’ It was a boy’s voice.

They all screamed. ‘In here! In here! We’re trapped!’ They banged on the door again.

‘Hold on!’ he said. ‘I have a key. Hold on! Stop banging!’

‘It won’t work!’ shouted Murph. ‘The lock’s fucked. Who’s that? Is that Patrick?’

‘Yes!’

‘Help!’ Edie started screaming. ‘It’s Edie! Help!’

‘Thanks be to fuck, Patrick!’ said Murph. ‘Thanks be to fuck!’

‘OK – wait! Wait!’ he said. ‘I’ll get something.’

‘Hurry up!’ said Edie.

‘Hurry the fuck up!’ said Laura.

They could hear him rattling around outside. ‘OK, OK. Stand back a bit.’

‘Jesus, I don’t know if we want to do that,’ said Murph.

‘You’ve not much choice,’ Patrick said. They could hear the sound of metal in between the door and the door frame. ‘Get back!’

They all held hands, and took a small step back. They heard the bang of a hammer against the metal, and the ping as it slid off.

‘Come on t’fuck!’ said Murph. ‘Jesus Christ! Hurry the fuck up!’

‘Shhh!’ said Helen, elbowing him. ‘You’re doing a great job, Patrick!’ she shouted. ‘Keep going. Keep going! Keep your eyes on it, your hand out of the way, and go.’

Patrick tried again and the door burst open. They all ran. When they were clear, Murph stood, bent over, his hands on his knees. ‘Jesus, sorry, lads. I’m so sorry. Fair play to you, Patrick. Fuck’s sake.’ He looked at the others. ‘Lads, – we need to get the fuck out of—’

‘Where’s Jessie?’ said Clare.

Everyone looked around.

‘What?’ said Patrick. ‘Was Jessie here?’

‘Yes!’ screamed Helen. ‘Yes! Oh my God!’

Patrick turned and ran back.

‘Edie – go!’ said Helen. ‘You’re the fastest. Go!’

Edie ran, quickly catching up with Patrick.

Murph looked at Laura. ‘Was she not hanging out of the back of you – Jessie?’

‘What are you on about?’ said Laura.

‘I told her hang on to your jacket,’ said Murph, ‘because it was white and she’d see it!’

‘I didn’t hear you!’ said Laura. ‘I didn’t hear anything about a jacket. I just thought she was coming out behind me!’

Edie and Patrick skidded to a stop at the side door to the dormitory as the wind tore a swathe from the black smoke billowing towards them. They froze. In the clearing, they saw Jessie standing, staring ahead, arms by her side. She was motionless, two steps from the exit, flames encroaching, high and loud and crackling. They screamed her name. She didn’t blink. They screamed again. Jessie closed her eyes, and they watched as she let the flames engulf her.

Edie grabbed for Patrick’s arm, clawing at it with desperate hands, her fingers digging into his flesh. They turned to each other, wild-eyed, mouths open, chests heaving. In the fractional moment their eyes met, they made an unspoken pact: they would never mention what they had seen to another soul.

Or maybe it was a shared granting of permission – to lose the memory to a confusion of smoke or shock.

4

Edie parked at the bottom of the steps to the inn. She glanced down at the folder on the passenger seat – research she had gathered on the history of Pilgrim Point. She wanted to be able to talk to the guests about it, or include interesting details on the website or in printed cards she would leave in the bedrooms. When she bumped into Murph the previous summer, she told him her plans, and the following day, when he was meeting Johnny in town, he transferred four boxes of his late father’s research into the boot of Johnny’s car.

Edie opened the folder and saw two pages, titled In a Manor of Silence. In all she had read about Pilgrim Point, the words of Henry Rathbrook were the ones that resonated the most – even when she learned that they were not an extract from the handwritten manuscript of a published book, but were among the scattered remains of patient files discovered in an abandoned asylum.

Edie pulled up the hood of her rain coat, tucked her hair inside, and made the short dash up the steps. She pushed through the front door, and let it close gently behind her. Look where my rich imagination got me, she thought. The hall was exactly how she had pictured it on the day of the viewing. But how it looked and how it felt were on two different frequencies. Did it matter that each beautiful choice she had made could light up the eyes of their guests if the pilot light in their heart had blown as soon as they walked through the door? She would watch their gaze as it moved across the floors and walls, up the stone staircase, along the ornate carvings of the cast iron balustrade, and higher again to the decorative cornices of the ceiling, the elaborate ceiling rose, and the sparkling Murano glass chandelier that hung from it. Then she would graciously accept the praise that always followed, pretending not to notice the small spark of panic in their eyes or the tremor in their smile.

It was as if a signal was being fired off inside them: no, we don’t smile at things like this, not in places like this, because something is not right. Something is wrong.

She would see some beautiful, eager young girl arriving with her young boyfriend who had spent a month’s wages on one weekend, and he would beam as her eyes lit up, but Edie would see the rest. She knew it wasn’t because this girl felt out of place – everyone was made to feel welcome at the inn because everyone was welcome. But sometimes Edie felt that the reason everyone was welcome was not because that was her job, not because the vast extravagance of the refurbishment had plunged them into an alarming amount of debt, not because a family has living expenses, and Dylan has to be put through college, but because she hoped that one day, someone would walk in and they would light up and it would be pure, there would be no strange aftertaste, and the spell would be broken.

Edie shook off her jacket and hung it on the carved oak hallstand. She paused as she heard the sound of a door slamming, and heavy footsteps echoing towards her.

‘Dad won’t let me go to Mally’s tonight!’ said Dylan, stomping half way across the hall. He stood with his hands on his hips, his face red, his chest heaving.

‘Dylan!’ said Edie. ‘Calm down, please.’

Johnny appeared behind Dylan.

‘And why does it even matter,’ said Dylan, glancing back at him, ‘when you’re all going to be here partying anyway?’

‘Partying?’ said Johnny. ‘It’s Helen’s forty-seventh birthday – we’re hardly going to be dancing the night away.’

Dylan looked at him, wide-eyed. ‘Oh my God! That is so mean!’

Johnny stared at him, bewildered.

‘Mom – did you hear that?’ said Dylan. ‘Just because Helen’s in a wheelchair.’

Johnny did a double take. ‘What?’ He looked at Edie, then back at Dylan. ‘Dylan – that had nothing to do with Helen being in a wheelchair. That was about us being so old that we don’t have the energy to dance.’