Полная версия

Face It: A Memoir

Television, oh, television. Glowing, ghostly seven-inch screen, round as a fishbowl. Set in a massive box of a thing that would’ve dwarfed a doghouse. Maddening electronic hum. Reception through this bent antenna. Some days good, some days rotten—when the signal flickered and skipped and scratched and rolled.

There wasn’t a whole lot to watch, but I watched it. On Saturday mornings at five A.M. I would be sitting on the floor, eyes glued to the test pattern, black and white and gray, mesmerized, waiting for the cartoons to start. Then came wrestling and I watched that too, thumping the floor and groaning, my anxiety levels soaring at this biblical battle of good vs. evil. My mom would holler and threaten to throw the goddamned thing out if I was going to get that worked up. But wasn’t that the point of it, getting all goddamned worked up?

I was an early and true devotee of the magic box. I even loved watching the picture reduce to a small white dot, then vanish, when you turned the set off.

When baseball season started, Mom would lock me out of the house. My mother, oddly, was a rabid baseball fan, and I mean rabid. She adored the Brooklyn Dodgers. They used to go to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn and watch the games when I was small. So I was always frustrated that I’d be locked outside for a baseball game. But I was a pest, I suppose—with a big mouth to boot.

My mother also liked opera, which she listened to on the radio when it wasn’t baseball season. As far as listening to music, we didn’t have much of a record collection though—a couple of comedy albums and Bing Crosby singing Christmas carols. My favorite was the compilation album I Like Jazz!, with Billie Holiday and Fats Waller and all these different bands. When Judy Garland launched into “Swanee,” I would burst into sobs every time . . .

I had a little radio too, a cute brown Bakelite Emerson that you had to plug in, with a light on the top and a funny old dial with art deco numbers like a sunburst behind it. I would glue my ear to the tiny speaker, listening to crooners and the big band singers and whatever music was popular at the time. Blues and jazz and rock were yet to come . . .

On summer evenings, a drum-and-bugle corps would practice in the parade ground just beyond the woods. These men, the Caballeros, would gather after work. They were just starting out and couldn’t afford uniforms, so they wore big navy-surplus bell-bottoms, white shirts, and Spanish bolero hats. They only knew how to play one song, which was “Valencia.” They would march back and forth all evening and sometimes they would dance, and you could hear the music drifting up from out of the woods. My room was up in the eaves of the house with little dormer windows, and I would sit on the floor with the windows open and listen. My mother would say, “If I hear that song one more time, I’m gonna scream!” But it was brass and snare and loud and I loved it.

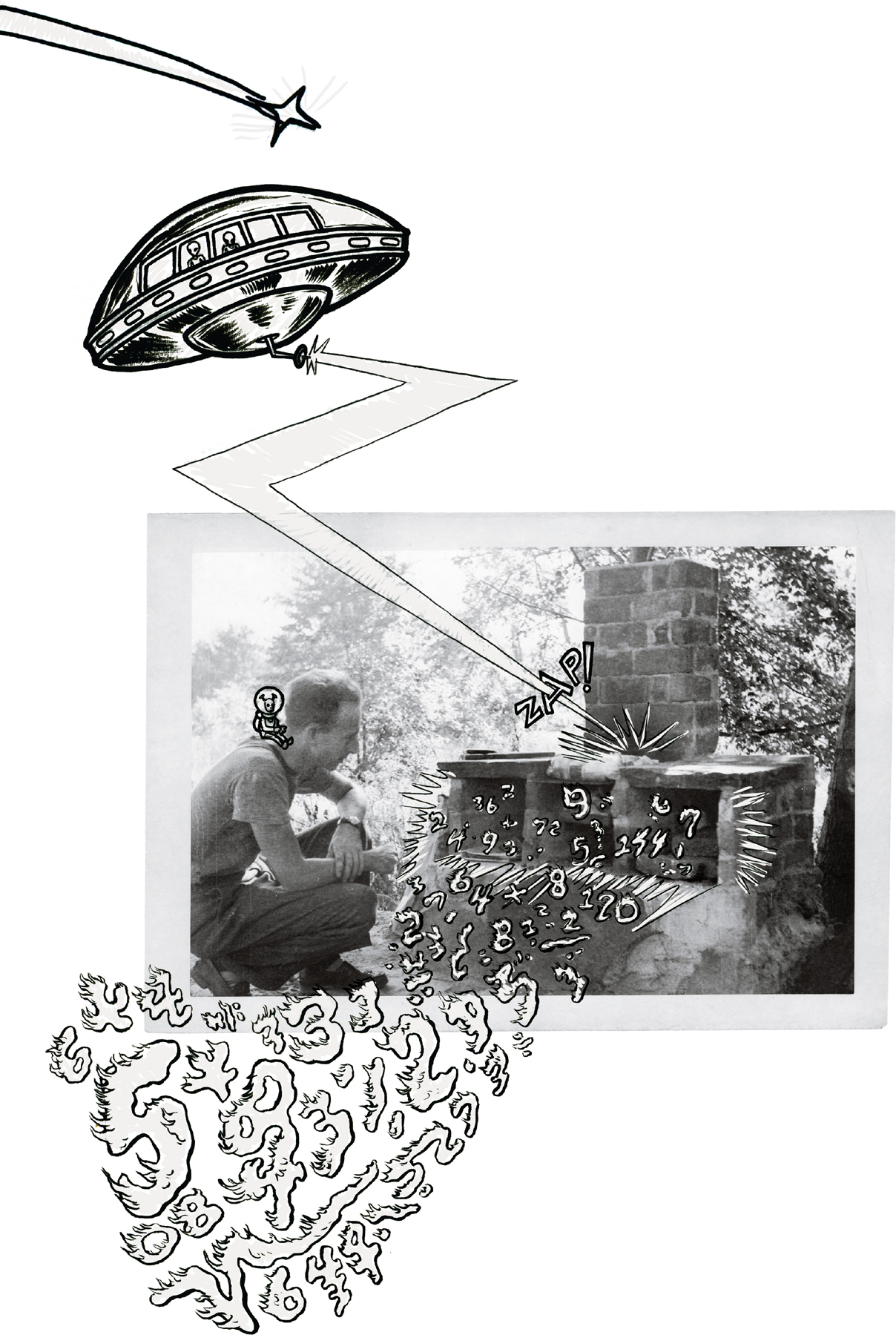

There were so few distractions then, before I started school, and I had so much time for daydreaming. I remember having psychic experiences as a little girl too. I heard a voice from the fireplace talking to me, telling me some kind of mathematical information, I think, but I have no idea what it meant. I would have all sorts of fantasies. I fantasized about being captured and tied up and then rescued by—no, I didn’t want to be saved by the hero, I wanted to be tied up and I wanted the bad guy to fall madly in love with me.

And I would fantasize about being a star. One sun-drenched afternoon in the kitchen, I sat with my aunt Helen as she sipped at her coffee. I could feel the warm light playing on my hair. She paused with the cup at her lips and gave me an appraising stare. “Hon, you look like a movie star!” I was thrilled. Movie star. Oh, yes!

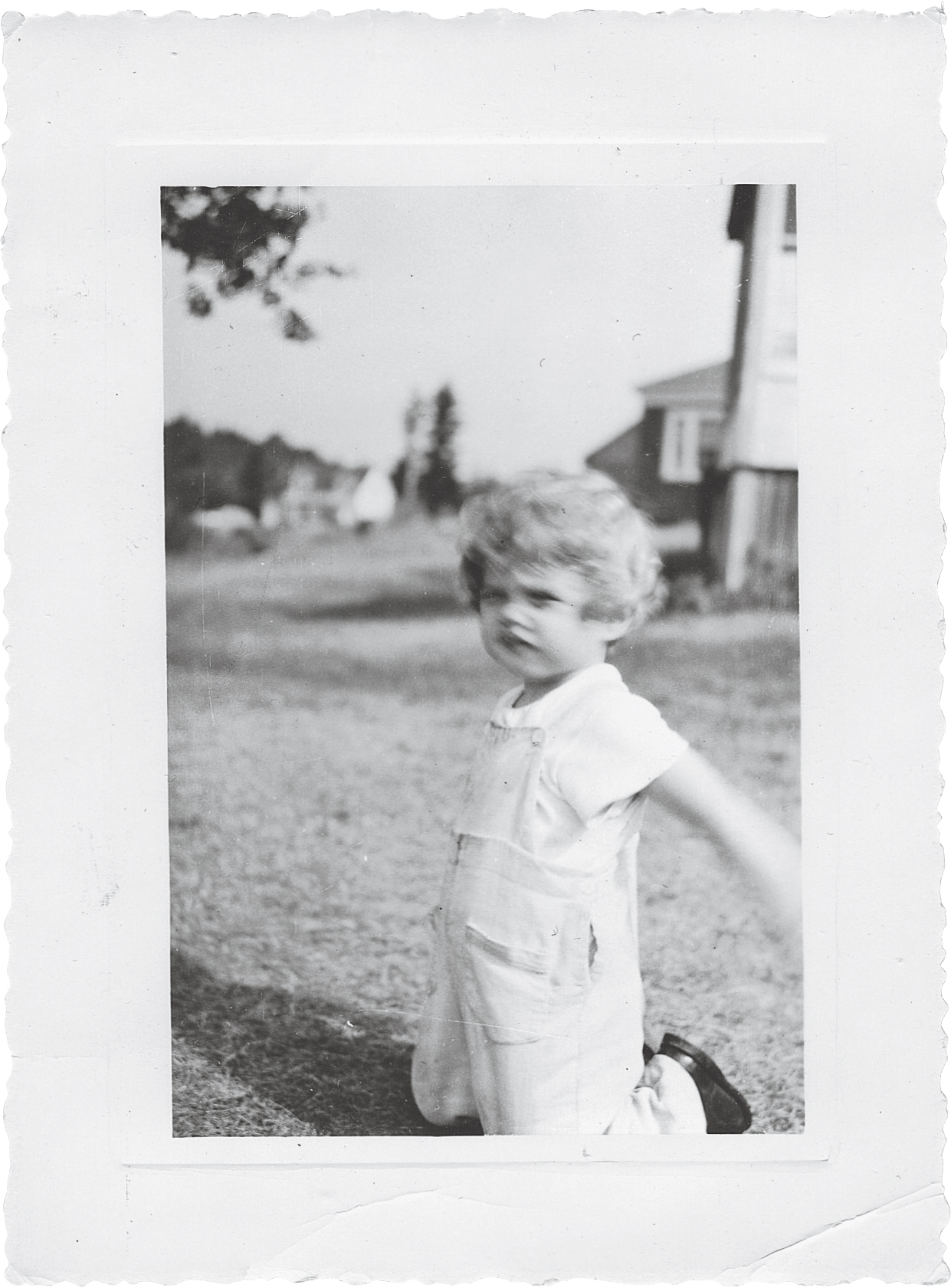

When I was four years old, my mom and dad came to my room and told me a bedtime story. It was about a family who chose their child, just like, they said, they had chosen me.

Sometimes I’ll catch my face in a mirror and think, that’s the exact same expression my mother or father used to have. Even though we looked nothing like each other and came from different gene pools. I guess it’s imprinted somehow, through intimacy, through shared experience over time—which I never had with my birth parents. I’ve no idea what my birth parents look like. I tried, many years later, when I was an adult, to track them down. I found out a few things, but we never met.

The story my parents told me about how I was adopted made it sound like I was someone special. Still, I think that being separated from my birth mother after three months and put into another home environment put a real inexplicable core of fear in me.

Fortunately, I wasn’t tossed into God knows what—I’ve had a very, very lucky life. But it was a chemical response, I think, that I can rationalize now and deal with: everybody was trying to do the best they could for me. But I don’t think I was ever truly comfortable. I felt different; I was always trying to fit in.

And there was a time, there was a time when I was always, always afraid.

2

Pretty Baby, You Look So Heavenly

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

One visit, when I was a baby, my doctor gave me a lingering look. And then he turned in his white coat, grinned at my parents, and said, “Watch out for that one, she has bedroom eyes.”

My mother’s friends kept urging her to send my photo to Gerber, the baby food company, because I was a shoo-in, with my “bedroom eyes,” to be picked as a Gerber baby. My mother said no, she wasn’t going to exploit her little girl. She wanted to protect me, I suppose. But even as a little girl, I always attracted sexual attention.

Jump-cut to 1978 and the release of Louis Malle’s Pretty Baby. After seeing the movie, I wrote “Pretty Baby” for the Blondie album Parallel Lines. Malle’s star was the twelve-year-old Brooke Shields, who played a kid living in a whorehouse. Nudes scenes abounded. The movie created a firestorm of controversy regarding child pornography at the time. I met Brooke that year. She had been in front of the camera since she was eleven months old, when her mother got her a commercial for Ivory Soap. At age ten, with her mother’s consent, she posed naked and oiled up in a bathtub for the Playboy Press publication Sugar and Spice.

One time, when I was around eight years old, I was put in charge of Nancy, a little girl of four or five, whom my mother was watching for the afternoon for her friend Lucille. I was to walk Nancy over to the municipal pool, which was about two blocks from my house, and my mother was going to join us there. I guided Nancy down the busy thoroughfare that bordered the end of the town, holding her little hand for safety. It was a seriously hot day, the bright hard sun bouncing up off the sidewalk at us. We turned a corner and were about to pass this parked car, with its passenger window rolled all the way down. From inside came this voice: “Hey, little girl, do you know where such-and-such is?” A messy-looking, rather nondescript older man, with washed-out and faded hair . . . He had a map over his lap, or maybe it was a newspaper. He was asking all kinds of questions and directions, and his one hand was moving around underneath the paper. Then the paper slid off and out popped his penis. He had been playing with it. I felt like a fly on the edge of a spiderweb. This wave of panic flushed through my body . . .

I freaked and fled to the pool, dragging Nancy along, her tiny feet trying to keep up. I rushed up to my teacher, Miss Fahey, who was at the entrance, making sure that everyone had their pool pass. I was really upset, but I just couldn’t tell her about this creep showing me his penis. I said, “Miss Fahey, please watch Nancy, I have to go home,” and I ran back. My mother was beside herself. She called the police. They came screeching up to the house and my mother and I rode around town in the back of the squad car, trying to spot the pervert. I was so small, I couldn’t see over the back of the seat. I just sat there as we rode around and around, peering over the seat as best I could, my heart pounding and pounding.

Well, that was an awakening. My first indecent exposer, although my mother said there were others. Once, we were stalked at the Central Park Zoo by a man in a trench coat who kept flapping it open. Because of their frequency, over time, these kinds of incidents started to feel almost normal.

For as long as I can remember I always had boyfriends. My first kiss was given to me by Billy Hart. How sweet to be initiated by a boy with such a name. I was stunned, alarmed, angry, pleased, excited, and enlightened. Maybe I didn’t realize all of this at the time and I probably couldn’t have put it into words; nevertheless, I was confused and conflicted. I ran home to tell my mother what had happened. She gave me a mysterious smile and said it was because he liked me. Well, up to that point I had liked Billy too, but now I was embarrassed and got all shy around him. We were very young, maybe five or six years old.

And then there was Blair. Blair lived up the street and our mothers were friends, so he and I sometimes played together. This one time, we went up to my room and we ended up sitting cross-legged on the floor, Indian style, facing each other and taking a good look at each other’s “things.” This was innocent too. I was about seven and he was maybe eight and we were curious. I’ve always been curious. Well, Blair and I must have been quiet for too long because our mothers came in and we got caught. They were more embarrassed than angry, being longtime friends, but Blair and I were never encouraged to play with each other again.

My parents held to traditional family values. They stayed married for sixty years, holding on through all the ups and downs, and they ran a tight ship at home. We went to the Episcopalian church every Sunday and my family was very much involved in all the church activities and its social life. Which may have been why I was in the Girl Scouts and was definitely why I was in the church choir. Fortunately, I really enjoyed singing, so much so that I won a silver cross when I was eight for “perfect attendance.”

I guess it’s not really until you approach your teens that you get all these doubts and questions about religion. I must have been twelve when we stopped going to church. My father had had a big falling-out with the rector or the minister. Anyway, by that time I was in high school and probably much too busy to go to choir practice.

I hated the whole process of arriving at a new school. It wasn’t the school itself. It was just a little local school, fifteen or twenty kids in each grade, and I wasn’t afraid of studying; I’d learned the alphabet before kindergarten. First, for some reason, I would get incredibly anxious about being late. Maybe I needed approval that badly. However, my bigger problem was separation—being separated from my parents. Abandonment. It was traumatic. I would be a nervous wreck. My legs would turn to jelly and I struggled to climb the stairs. I guess somewhere in my subconscious, a scene was playing on a loop of a parent leaving me somewhere and never coming back. That feeling never really went away. To this day, when the band separates at the airport and we all go our different ways, I still get that gut reaction. Separation. I hate parting with people and I hate goodbyes.

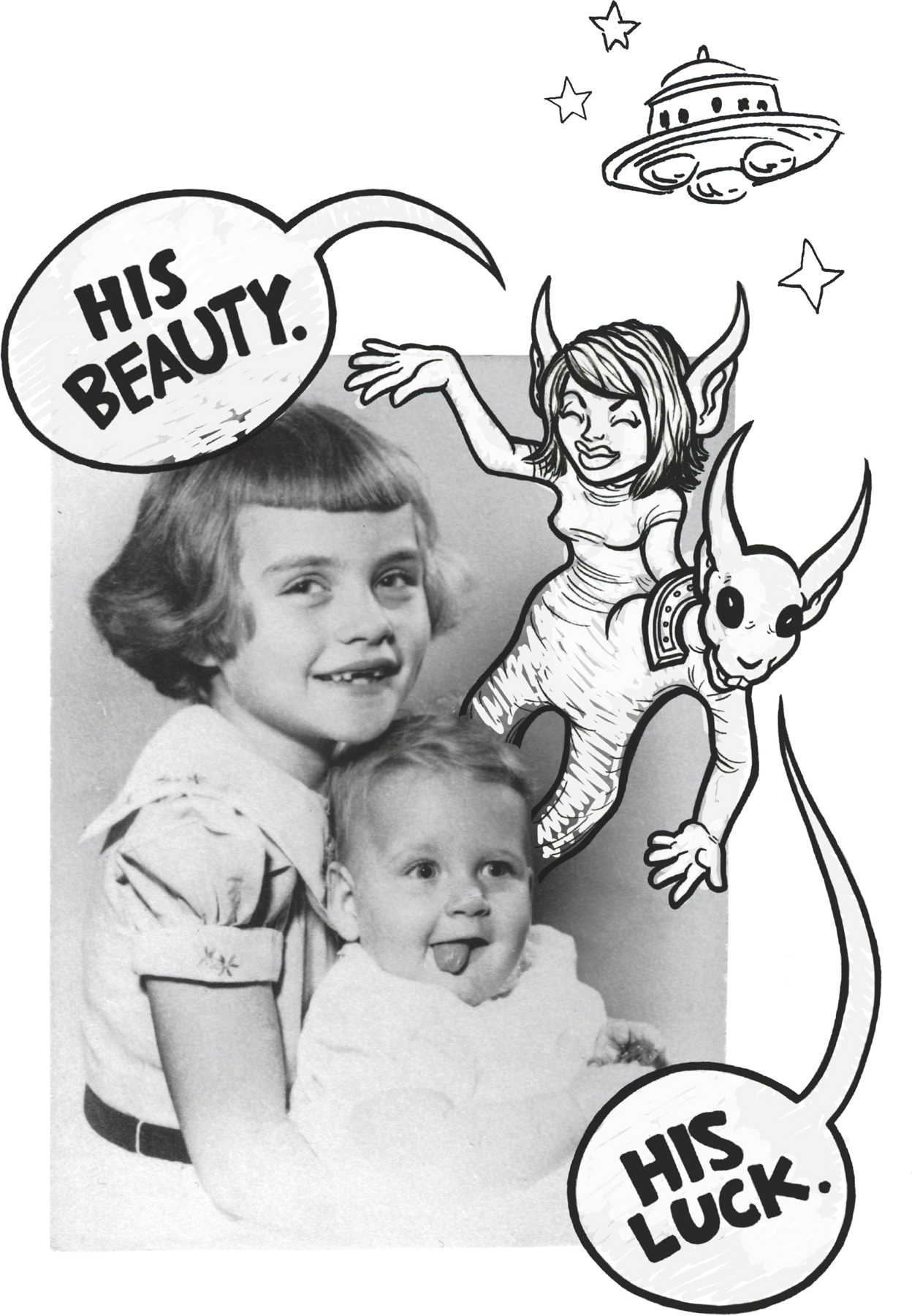

Things were changing at home. At the age of six and a half, I had a baby sister. Martha was not adopted; my mother gave birth to her after a really rough pregnancy. Around five years before she adopted me, my mom had had another baby girl, Carolyn, premature I think, who died of pneumonia. There was a boy too, whom she miscarried. Then a drug came along that helped her go to term. Martha was premature, but she survived. My father said her head was smaller than the palm of his hand.

You might have thought that the arrival of another pretty baby in my house—and one that actually came from my mom—might have triggered my insecurity and abandonment fears. Well, at first I was probably a little disturbed by not being the complete focus of all my mother’s attention, but more than anything else I loved my sister. I was always very protective of her because she was so much younger than me. My father called me his beauty and my sister his good luck, because when she was born his fortunes changed.

Sean Pryor

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

I scared my parents one morning. It was probably the weekend and they were sleeping in a little bit. Martha had woken up and was crying for her bottle. So, I slipped down to the kitchen and heated up the bottle, which I had watched my mother do so many times, and I brought it upstairs and gave it to her. My parents freaked when they discovered what I was up to, convinced that I was scalding her. But there Martha was, happily chomping down on that nipple . . . So, I found myself with a new job, which became my morning contribution to all the many routines in our Hawthorne home.

Hawthorne was the center of my universe then. We never left. I didn’t understand about finances as a young child and I didn’t grasp that there wasn’t much money and my parents were trying to save up to buy a house. All I knew was that I had a powerful yearning to travel. I was so curious and restless all the time. I loved it when we would all pile into the car and drive to the beach on our vacations, which almost always meant visiting family.

One year—I must have been eleven or twelve—we went on vacation to Cape Cod. We were staying in a rooming house with my aunt Alma and uncle Tom, my dad’s brother. My cousin Jane was a year older than me and we had lots of laughs, giggling and playing together. One particular day, while our parents were downstairs, we sat in front of the mirror fixing our hair, as we loved to do. But this time, we called down and said we were going for a walk. As soon as we were far enough away, we took out our stolen pile of lipstick and eye makeup and carefully transformed ourselves into these hot-looking babes. We probably looked like two nubile characters from The Rocky Horror Picture Show. We stopped at a stand to buy some lobster rolls, then strolled on down the street, admiring our reflections in the shop windows. But we weren’t the only ones admiring ourselves: these two men approached us and started to come on to us. They were way, way older than us. Both in their late thirties, we would discover. Pretending to have no idea that we were actually preteens, they invited us out that night and said they’d meet us at our place. Of course, we were not going to tell them our address, but we played along and said we’d come back and meet them somewhere else.

That night, our faces scrubbed clean, we were in bed playing cards and wearing our baby-doll pajamas when there was a knock on the door. It must have been eleven o’clock. Without our noticing, the two guys had followed us home and they were there to pick us up. I think by then our parents had enjoyed a few cocktails and they just thought it was hilarious. So, they threw open the bedroom door and there we were, children. It turned out that we didn’t get into too much trouble. It also turned out that one of our suitors was a very famous drummer, Buddy Rich. I later discovered that, besides being a close friend of Sinatra’s, Buddy had been married at the time to a showgirl named Marie Allison. They remained together until his death from a brain tumor at age sixty-nine, in 1987. Shortly after his visit, a large envelope arrived in the family mailbox. Inside was an autographed, eight-by-ten black-and-white glossy of my Buddy, who was once hailed as “the greatest drummer who ever drew breath.”

Interestingly, Buddy Rich returned as a presence in my life decades later, when some of my close colleagues in the British rock scene—like Phil Collins, John Bonham, Roger Taylor, and Bill Ward—would count Buddy as their greatest influence . . . My life has so often circled back on itself in these intricately obscure ways.

There was a whole lot going on that year, now that I look back on it. It was the year I made my stage debut. It was a sixth-grade school production of Cinderella’s Wedding. They didn’t give me the part of Cinderella, but I was the soloist who sang at her wedding to the prince. The song I sang was “I Love You Truly,” a big ballad featured in the movie It’s a Wonderful Life. When I came onstage I had the worst stage fright—all those eyes staring at me, kids, teachers, parents; my mom and dad were there with my sister, Martha. But I pulled it together. I just wasn’t a natural performer or a big personality. I think I had a big personality inside, but I didn’t have one on the outside; I was very shy. Whenever the teacher would come up to me and say, “You were so good!” my misfit mind added an unspoken, “Not really, have you lost your mind?”

My experience with ballet wasn’t really much better. Like a lot of little girls, I wanted to be a ballerina. I’d been exposed to Margot Fonteyn and other wonderful dancers by my mother, who’d had a cultured childhood and wanted me to have some of that experience. But in ballet class I always felt very self-conscious because I was convinced I was too fat, which I wasn’t at all. I had an athletic body. But I wasn’t birdlike and delicate like all the little girls who looked so cute and perfect and like each other in their little tutus. I felt that I fucked the whole thing up by being so chubby and standing out.

The biggest thing that happened that year was that my family finally bought that little house and we moved. Our new neighborhood was not much different from our old one and it was not very far away. But it was in another school district, which meant that I had to switch schools. It was not easy being the new kid in sixth grade. I didn’t know anybody there, apart from two girls I knew from Girl Scouts. I had no friends. Even more startling, Lincoln School had a whole different curriculum, which was much more focused on academics than my old school, so I had a lot of work to do to catch up. But there was a silver lining to this very dark cloud, I told myself. Which was: no more Robert.

Martha and me.

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

Sean Pryor

Robert was a new boy at my old school and he was a different kind of kid, kind of wild and dressed in clothes that were usually too big for him. His clothes were very messy. His hair was messy too. Even the features on his face were messy. He also had a problem with wetting his pants. His sister Jean, on the other hand, was a model of perfection with pretty, curly hair; she was nicely dressed and brainy, maybe top of her class. Robert’s grades were so low they couldn’t be measured. He was the class freak. Mostly he was avoided or made fun of.

Perhaps because I was less cruel to him than the other kids, Robert became fixated on me. He started following me home. Sometimes he would leave me little presents. This went on and on. But since we were in a different house and I didn’t go to that school anymore, I thought I would be free from his hauntings. I wasn’t. We had been in the new house for just a few days and I was standing at the front door. My sister, Martha, asked me a question about Robert and I just let rip. I said exactly what I felt about his unwanted attentions. I did not know that Robert was outside, hiding behind a tree. He heard everything. I will never forget the look of astonishment and pain on that boy’s face as he slipped away. I felt awful. I never saw him again, but from what I heard he remained a social catastrophe and in high school he hung out with another outcast. They would go hunting. A few years later, when they were fooling around with guns in Robert’s basement, his friend shot him dead and this was ruled an accidental shooting, kids playing with guns.

Summers were for wandering in the sun, my mind running free. The days so muggy it felt like being swaddled in a hot compress. I swam and did all those summer things and I read a lot—everything I could get my greedy little hands on. Literature was my great escape and my expedition into other worlds. I hungered to learn about everything and everywhere that was beyond Hawthorne. And there were family outings to see my grandparents and aunts and uncles. Just the usual kid stuff, all of it a blur now, except for that deep, sinking sensation of dread in my stomach at the thought of going back to school.

Hawthorne High was my third school. I can’t say I liked it any better than the others. It made me nervous, but I did like the sense of freedom and independence that came along with going to high school, where you’re treated a little more like an adult. My parents made it pretty clear that they wanted me to be an achiever. And if they hadn’t pushed me in this way, I think I might have just wandered off into dreamland. I was still trying to discover who I was, but I knew even then that I wanted to be some kind of artist or bohemian.

My mother used to make fun of artists. She would put on a WASP-y accent, make one wrist go limp, and exclaim, “Oh, you are such an artiste.” That made me even more nervous and annoyed, and there’s nothing worse than an angry and pissed-off teenager. Now, my life was not awful; it was blessed. My parents heaped so much love on me. But I felt like I had a split personality with half of the split missing, submerged, unexpressed, unreachable, and hidden.

I didn’t make trouble at high school and my grades, although not straight A’s, were good. I actually liked the classes where we were given literature to read, and I got good at geometry, because it was like figuring out a puzzle. One of the first things I noticed about high school was how much more grown-up the girls were, particularly their clothes. I immediately became extremely conscious of my clothes, which were either too dull, too constricting, or both. My mother dressed me like a little preppy girl, clean-cut American, with clunky shoes. What I wanted to wear was tight black pants and a big loose shirt or a back-to-front sweater, like the beatniks, or something tough looking and ballsy. Or at least something jazzier, with bright colors or a fringe. But when my mom took me shopping she would go straight for a white blouse with a round collar and a navy-blue skirt. Basically, when it came to clothing choices, my mother and I were always poles apart.

As I got older, life looked up. I started making my own clothes. I would fool with things, some of them hand-me-downs, tearing the sleeves off of one piece and sewing them onto another. I remember showing this one concoction to perhaps my first friend, Melanie, who remarked, “It looks like a dead dog.” I have no idea where that dead dog went.

But for the longest time, I held on to one of those dresses I inherited from my mother’s friends’ daughters. I see it clearly now: this pink cotton summer dress with its full skirt and its great movement. Later, my father would take me to Tudor Square, one of his clients in the garment industry. And I remember getting a couple of brightly colored, really cool tweedy plaid outfits that I kept for a long time.

By the time I was fourteen, I was dyeing my hair. I wanted to be platinum blond. On our old black-and-white television and at the theater where they screened Technicolor movies, there was something about platinum hair that was so luminescent and exciting. In my time, Marilyn Monroe was the biggest platinum blonde on the silver screen. She was so charismatic and the aura she cast was enormous. I identified with her strongly in ways I couldn’t easily articulate. As I grew up, the more I stood out physically in my family, the more I was drawn to people that I felt I related to in some significant way. With Marilyn, I sensed a vulnerability and a particular kind of femaleness that I felt we shared. Marilyn struck me as someone who needed so much love. That was long before I discovered that Marilyn had been a foster child.