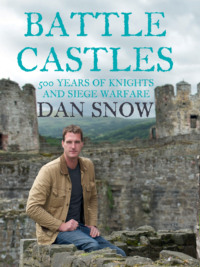

Death or Victory: The Battle for Quebec and the Birth of Empire

Полная версия

Death or Victory: The Battle for Quebec and the Birth of Empire

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу