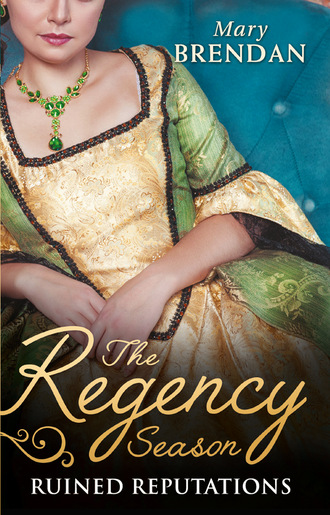

Полная версия

The Regency Season: Ruined Reputations

‘And I do thank you for it. But I am not afraid, Elise, of gossip or of Hugh Kendrick.’ Bea knew that was not quite truthful and hastened on. ‘So, I will remain here, quite content, though I pray your mother-in-law will recover.’ Bea looked reflective. ‘She was very kind to us at your wedding reception and made sure Papa and I had servants dancing attendance on us. She introduced us to so many people, and Papa was glad to renew his acquaintance with her that day. He told me he had liked her late husband too.’

‘Susannah is a dear soul...’ Elise frowned, folding linen with renewed vigour. ‘I must quickly get back and visit her. I’m sure the doctor is right, though, and she’s already on the mend.’

Beatrice comforted her sister with a hug. ‘She will be fine, Elise. The dowager will be up and about again in no time...’

* * *

‘I should like to attend.’

‘Are you feeling up to the journey, Papa?’ Beatrice asked in concern.

The post had arrived just ten minutes ago. Alex’s bold black script had been on one of many letters Bea, with heavy heart, had brought to her father’s study. Walter had opened it at once. There had been a note for her too, from Elise, but Beatrice had slipped that into the pocket of her skirt and would read it later.

The other letters, she surmised, were replies from the guests who’d been informed by her father last week that the wedding would not be taking place. She recognised Mr Chapman’s hand, and also that of her Aunt Dolly on two of the five sealed parchments. Bea felt sure all would contain messages of sympathy and encouragement for her, but she didn’t yet want to know about any of it.

Neither did Walter, it seemed. Bea’s father left untouched the pile of post and continued sighing and polishing his glasses with his handkerchief.

‘Are you sure the journey will not excessively tire you?’ Beatrice rephrased her question in an attempt to draw her father’s attention.

‘I will bear a few discomforts to pay my respects to Susannah Blackthorne.’ Walter dabbed a handkerchief at his watering eyes. He put his glasses on, then held up Alex’s letter so he might again scan the sad news that his son-in-law’s mother had passed away. The funeral was to be held in a few days’ time and Alex had offered to send his coach for Walter and Beatrice so they might join the mourners at Blackthorne Hall. He had added that he hoped very much they would attend as his mother had enquired after the two of them only recently.

‘You will come as well, my dear, won’t you? I should not like to travel alone.’ Walter raised hopeful eyes to his daughter.

‘Of course I shall come with you, Papa!’ Beatrice replied. ‘I would not want to miss it.’

Walter nodded, content. ‘I shall write a reply and get Norman to quickly despatch it to Berkshire. I don’t like imposing on the viscount’s generosity but we must accept the use of his transport.’

‘Alex will be cross if you do not! I expect he and Elise are feeling very low and will be glad to see us as soon as maybe.’

‘As a family we lately seem to be in the doldrums more often than not.’ Walter dropped the letter to the desk, drawing forward his quill and a plain parchment. ‘Susannah was a very vivacious woman...and more than ten years my junior.’ He dipped the pen into ink. ‘I’m getting quite ancient now...’

‘Don’t be so maudlin, Papa!’ Beatrice dropped a light kiss on the top of her father’s sparsely covered crown. ‘You are a mere spring chicken.’

She could tell he was feeling quite depressed at the news of the dowager’s death. Bea had noticed that as he aged her father acted increasingly sentimental when hearing about sad or happy events.

As Walter’s quill began scratching on paper she turned for the door, informing him, ‘I’ll start to pack a few things.’

Beatrice took down her carpetbag from the top of the clothes press. She blew dust off it and set it on her bed’s coverlet. It seemed she would be taking a trip to stay with her sister after all, but glumly wished something nicer had prompted it.

* * *

As the viscount’s well-sprung travelling coach bounced over a rut the letter in Bea’s hand fluttered from her fingers to the hide seat. She retrieved it and recommenced reading. It had arrived that morning, before she and her papa had set on the road for Berkshire, and had been sent by Fiona Chapman. Bea had known the identity of the sender as soon as she spied her name written in elegant sloping script. But it had only been moments ago when her papa, seated opposite, ceased chattering and started dozing that she’d drawn her friend’s note from her reticule and unsealed it.

As expected, the message bore very kind and sincere wishes to boost her morale following her jilting. Bea had already received fulsome sympathy from Aunt Dolly and Fiona’s father. Walter had shown to her the letter from Mr Chapman and Bea had had to smile at Anthony’s robust defence of her reputation. In his honest opinion Walter’s daughter was too good for the physician in any case, and the whole matter was a blessing in disguise for Beatrice. Anthony had emphasised that observation with a very large and forceful exclamation mark that had punctured the paper.

‘My sentiments exactly,’ Walter had barked, perking up on reading it. Then he’d promptly helped himself to port from the decanter on the edge of his desk.

But now, as Beatrice’s blue gaze landed on the final paragraph of Fiona’s letter, she gasped at the startling news it contained. Mr Kendrick, Fiona wrote, had put a flea in Colin Burnett’s ear over vulgarly flaunting his new fiancée before anybody in town had been given the news that he’d jilted his former bride-to-be. Bea’s eyes sped on over the paper. The clash had taken place at her sister Verity’s home, Fiona informed her, and Mr Kendrick had threatened, very discreetly—Fiona had underlined those two words—to throw the doctor out if he didn’t go before people started asking awkward questions. Colin had bowed to Mr Kendrick’s dictate and slunk off with his tail between his legs, Fiona penned in conclusion, before signing off with affection and good wishes.

Beatrice felt her heart thudding in consternation and her cheeks glowing despite the breeze from the window. The last thing she’d wanted was any fuss about the affair, because it would be sure to give an impression that she was bitter and jealous over it all. And whereas for a short while those emotions had overtaken her, they had now faded away. Or so she’d thought...

Beatrice slowly reread that ultimate paragraph. She was irked that Colin could treat her so shabbily when less than a month ago he’d said it was her he loved and would marry if only he could. She pondered then on Stella, and whether the girl was pretty, and if Colin had quickly fallen in love with her.

In which case, Beatrice impatiently scolded herself, he is the most dishonest and fickle man alive and you should pray you never again are foolish enough to be taken in by his like.

Having mentally shaken herself, she turned her thoughts to Hugh Kendrick. So he had championed her, had he? She wondered why that was. Their recent meeting had been frosty, if civil. She stared through the coach window and twisted a smile at the passing scenery. Perhaps the aim of his gallant intervention had been to impress Fiona. Beatrice recalled that he had courted her friend a few years ago; perhaps Mr Kendrick was of a mind to do so once more as they were both still single and Fiona was a minor heiress. At her sister’s wedding reception Hugh had partnered Fiona in the ballroom and Bea recalled thinking they had looked happy together...

Bea folded the note without again looking at it, putting it back into her reticule, then rested her head against the squabs. Behind her drooping lids two couples were dancing and laughing. The gentlemen had both once professed to want her as a wife. Beatrice huffed a sigh, wishing for a nap to overcome her so she might have a respite from her irritating fantasies.

Wearily she again watched the verdant landscape flashing past, but the same thoughts were haunting her mind. Colin and Stella would be the first to get married: no long engagement for him this time, as he now had enough money to set up home immediately. If Hugh Kendrick were intending to propose to Fiona, and her friend were to accept him, Bea would make sure she was one of the first to send congratulations...

‘You are sighing louder than the wind outside.’ Walter had one eye open and was watching his daughter’s restless movements from beneath a thick wiry brow.

‘It is rather gusty...’ Bea pulled the blind across the window to protect the coach interior from draughts.

‘Have you read your letter?’

‘Mmm...’ Bea guessed her father was keen to hear what was in it.

‘I have lately shared my missives from London with you,’ Walter wheedled, giving her a twinkling smile.

Beatrice smiled, swayed by his mischievous manner. ‘Oh, very well... Fiona Chapman has written to me more or less echoing her father’s thoughts on Dr Burnett.’

‘Oh...is that it? No other news?’ Walter queried. He’d watched his daughter from between his sparse lashes while she’d been reading and had been sure he’d heard a muted cry of dismay. Not wanting to immediately pry, he’d waited till she seemed more herself before letting her know he was awake.

Walter had felt very protective of Beatrice since the doctor had broken her heart. The more she put a brave face on it, the more he desperately wanted to make it all come right for her. He’d guessed the cause of her distress was reading about some antic of Burnett’s reported in her letter.

‘I’ve just had news that Colin turned up at Verity’s house, but it was made clear he was unwelcome, so he left.’

Walter struggled to sit upright. ‘Did he, by Jove?’ Gleefully he banged his cane on the floor of the coach, grunting a laugh.

Bea nodded, suppressing a smile at her father’s delight on hearing about her erstwhile fiancé’s humiliation. ‘Miss Rawlings was there too.’

Walter thumped the cane again, in anger this time. ‘How dare he treat you like that? Damned impertinence he’s got, squiring another woman so soon. I’ve a mind to bring it to his notice.’

‘I believe Mr Kendrick has beaten you to it, Papa...’

‘So it was that fellow, was it?’ Walter nodded. ‘That’s twice he’s done us a favour in a short space of time. Hugh Kendrick has just gone up considerably in my estimation. I suppose I must find an opportunity to tell him so.’ He grimaced, remembering how rude he’d recently been to Hugh.

Beatrice settled back into the seat, niggling anxieties again assailing her. Just how much of a good deed had Mr Kendrick done her? She feared that embarrassing rumours about the jilting might even now be circulating, and would only be worsened by talk of two gentlemen—both past loves of hers—arguing in public over her.

Chapter Seven

‘Alex seems to be bearing up well.’

‘Oh, he is a stoic soul and keeps busy all the time to take his mind off things.’ Elise met her sister’s eyes in the mirror. ‘But I believe at a time like this he misses having brothers or sisters to talk to.’

Beatrice was seated on her sister’s high four-poster bed, watching the maid put the finishing touches to Elise’s coiffure. At breakfast that morning Alex had seemed very composed, despite it being the day of his beloved mother’s funeral. It was the late dowager’s daughter-in-law who was having difficulty turning off the waterworks.

As Elise stood up from the dressing stool, pulling on her black gloves, Beatrice relinquished her soft perch and embraced her sniffling sister. ‘Alex has you to comfort him, my dear...and I’ll wager he’s told you already that’s enough family for him.’

Elise nodded, wiping her eyes. ‘Susannah wouldn’t want any wailing; she said so before falling into a deep sleep. Of course she knew the end was near, but she slipped away peacefully.’ Elise suddenly crushed Bea in a hug. ‘Thank you for coming.’

‘Did you honestly think I would not?’ Beatrice asked gently.

Elise shook her head. ‘I knew you would not let me down.’

‘You have never let me down, have you?’ Bea stated truthfully, remembering a time when Elise had been unstintingly loyal. Elise, though exasperated with her, had continued risking censure despite Bea’s shockingly selfish and daft actions. To her shame, Bea knew her behaviour had been at its worst during her infatuation with Hugh Kendrick. She’d made quite a fool of herself over him, much to Elise’s dismay. But today Bea was determined to banish thoughts of her own upset from her head. And that was not an easy task as Elise had let on that Hugh Kendrick was due to attend the funeral if he could escape his commitments in London.

‘Come...dry your eyes again,’ Bea prompted gently. ‘If we are to visit the nursery before we go downstairs Adam will not want to see his mama blubbing.’

Having left the darling baby in the care of his nurse, the ladies joined the other mourners. A hum of conversation, interspersed by muted laughter, met the sisters on entering the Blackthornes’ vast drawing room. It was crowded with people and Beatrice was glad that the atmosphere seemed relaxed despite the sombre occasion. They headed towards their papa, who was standing by the wide, open fire. Walter was alternately warming his palms on his hot toddy and on the leaping flames in the grate. It was mid-May, but the weather was cool for the time of the year.

‘I hope the showers hold off,’ Alex said, turning from his father-in-law to greet his wife and sister-in-law.

Elise slipped a hand to her husband’s arm, giving it an encouraging squeeze.

‘Are you warm enough, Papa?’ Bea asked. ‘Would you like a chair brought closer to the fire so you may be seated?’

‘I’m doing very well just where I am, thank you, my dear. My old pins and my stick will keep me upright for a while longer.’

‘You must sit by me in the coach when we follow the hearse to the chapel—’ Elise broke off to exclaim, ‘Ah, good! Hugh has arrived; he’s left it to the last minute, though.’

Beatrice felt her stomach lurch despite the fact she had discreetly been scouring the room for a sight of him from the moment she’d entered it. Casually she glanced at the doorway and felt the tension within increase. He looked very distinguished in his impeccably tailored black clothes, and she noticed that several people had turned to acknowledge his arrival.

‘Has it started to rain?’

Alex had noticed the glistening mist on his friend’s sleeve as Hugh approached.

‘It’s only light drizzle, and the sun’s trying to break through the clouds.’

Hugh’s bow encompassed them all, but Bea felt his eyes lingering on her so gave him a short sharp smile.

‘Come, my dear...’ Alex turned to Elise, having noticed a servant discreetly signalling to him. ‘The carriages are ready and it’s time we were off.’

The couple moved ahead and Beatrice took her father’s arm to assist him. Hugh fell into a slow step beside them, remaining quiet as they filed out into the hallway.

‘You must get in the coach with Elise, Papa.’

‘And you will come too?’ Walter fretted.

‘If there is sufficient room I will; but you must ride with Elise in any case.’

Beatrice was used to walking. Living in the country, she often rambled many miles in one day, especially in the summer. She walked to the vicarage to take tea with Mrs Callan and her daughter when no immediate excuse to refuse their invitation sprang to mind. She’d also hiked the four miles into St Albans when the little trap they owned for such outings had had a broken axle and no soul passed by in a cart and offered her a lift. A march to the chapel at Blackthorne Hall was an easy distance to cover for someone of her age and stamina. But her father would struggle to keep his footing on the uneven, uphill ground.

Bea glanced at the people in the hallway; many looked to be decades her senior. From glistening eyes and use of hankies she guessed that Susannah had been truly liked by her friends, neighbours and servants.

‘I’ve no need of a ride, Alex,’ Bea whispered, nodding at some elderly ladies close by, dabbing at their eyes. ‘There are others more deserving.’ She stepped outside onto the mellow flags of a flight of steps that cascaded between stone pillars down to an expanse of gravel. At least half a dozen assorted crested vehicles were lined up in a semi-circle, ready for use. The glossy-flanked grey and ebony horses appeared impeccably behaved as they tossed regal black-plumed heads.

Beatrice noticed that a column of mourners was snaking towards the chapel. Pulling her silk cloak about her, she started off too, at the tail-end of it.

‘The sun seems reluctant to escape the clouds.’

Beatrice’s spine tingled at the sound of that familiar baritone. Hugh Kendrick was several yards behind but had obviously addressed her as no other person was within earshot. He seemed to be casually strolling in her wake, yet with no obvious effort he had quickly caught her up and fallen into step at her side.

‘It is an unwritten law that funerals and weddings must have more than a fair share of bad weather.’ Bea’s light comment was given while gazing at a mountain of threatening grey nimbus on the horizon. To avoid his steady gaze she then turned her attention to the rolling parkland of Blackthorne Hall that stretched as far as the eye could see. The green of the grass had adopted a dull metallic hue beneath the lowering atmosphere.

‘Were you preparing for showers on your own wedding day?’

Beatrice was surprised that he’d mentioned that. A quick glance at his eyes reassured her that he hadn’t spoken from malice. She guessed he wanted to air the matter because, if ignored, it might wedge itself awkwardly between them. She was hopeful he shared her view that any hostilities between them should be under truce today.

‘I was banking on a fine day in June, but one never knows...and now it is all academic in any case.’

A breeze whipped golden tendrils of hair across her forehead and she drew her cloak closely about herself. She scoured her mind for a different topic of conversation but didn’t feel determined to rid herself of his company.

‘It seems the dowager was liked and respected by a great many people. My father has sung her sincere praises and those of her late husband.’

‘They were nice people. The late Lady Blackthorne was always kind and friendly to me. I was made to feel at home when I spent school holidays with Alex here at the Hall.’

Bea smiled. ‘You have known each other a long time?’

‘More than twenty years.’

‘I expect you were a couple of young scamps.’

‘Indeed we were...’ Hugh chuckled in private reminiscence, then sensed Bea’s questioning eyes on him. ‘Please don’t ask me to elaborate.’

‘Well, sir, now you’ve hinted at your wickedness I feel I must press for more details.’ A teasing blue glance peeked at his lean, tanned profile.

‘Just the usual boyish antics...climbing trees, catching frogs and tadpoles, building camp fires that rage out of control,’ Hugh admitted with a hint of drollery.

‘A fire...out of control?’ Beatrice echoed with scandalised interest.

‘It was a dry summer...’ Hugh’s inflection implied that the drought mitigated the disaster. ‘Luckily for us the old viscount remained reasonably restrained when learning that his son and heir together with his best friend had burned down a newly planted copse of oak saplings while frying eggs for their supper.’

Beatrice choked a horrified laugh. ‘Thank goodness neither of you were injured.’

‘I burned myself trying to put the fire out...’ Hugh flexed long-fingered hands.

Bea had never before noticed, or felt when he’d caressed her, that area of puckered skin on one of his palms. She recalled his touch had always been blissfully tender. Quickly she shoved the disturbing memory far back in her mind before he became puzzled as to what he might have said or done to make her blush.

‘It was quite an inferno,’ Hugh admitted. ‘It frightened the life out of the viscountess; she made Alex and me amuse ourselves indoors for the rest of the holiday. We rolled marbles with bandaged hands till we were sick of the sight of them. Even when the physician told us we were fit to be let out we were kept confined to barracks. But I wasn’t sent home in well-deserved disgrace.’ His boyish expression became grave. ‘I could give you many other instances of Susannah’s kindness and tolerance.’

Beatrice realised that Hugh was as moved by Susannah’s passing as had been the weeping ladies in the Blackthornes’ hallway. But of course he would not show the extent of his feelings: once, when a personable chap rather than a diamond magnate, he might have been less inclined to conceal his sadness behind a suave mask. Quietly she mulled over the theory of whether gentlemen felt it was incumbent on them to foster an air of detachment as they became richer.

‘And what mischief did you get up to in your youth, Miss Dewey?’

Bea glanced up with an impish smile. ‘Young ladies are never naughty,’ she lectured, before tearing her eyes free of his wolfish mockery.

‘I seem to recall a time, Beatrice, when you were very naughty indeed...’

‘Then I advise you to forget it, sir, as it is now of no consequence,’ she snapped. She tilted her chin and strode on, but no matter how energetic her attempt to outpace him he loped casually right at her side.

‘But you don’t deny it happened?’ he provoked her.

‘I have nothing to say on the subject other than you are very ill-mannered to bring it up.’

‘My apologies for upsetting you...’

He’d spoken in a drawling voice that made Bea’s back teeth grind together. ‘You have not done so,’ she replied, in so brittle a tone that it immediately proved her answer a lie.

‘Of course we were talking about childhood. I alluded to a time when you were most certainly a woman, and I admit it was not fair to do so.’

Bea said nothing, despite his throaty answer having twisted a knot in her stomach. She again contemplated the countryside, presenting him with her haughtily tilted profile.

‘So, did you enjoy your schooldays? How did you spend them, Beatrice?’ His tone had become less challenging, as though he regretted having embarrassed her by hinting at her wanton behaviour with him.

‘When we lived in London Elise and I were schooled at home by Miss Dawkins,’ Bea responded coolly. A moment later she realised it was childish to remain huffy. He’d spoken the truth, after all, even if it was unpalatable. ‘I was almost fifteen when we moved to Hertfordshire, so there was little time left to polish me up. Papa did engage a governess for Elise, and the poor woman did her best to prepare me for my looming debut.’ An amusing recollection made her lips quirk. ‘She despaired of my singing and piano-playing and told Papa he had wasted his money buying an instrument that neither of his daughters would ever master.’

‘What did Walter say to that?’ Hugh asked, laughter in his voice.

‘I cannot recall, but I expect he was disappointed to have squandered the cash; we were quite hard up by then—’ Beatrice broke off, regretting mentioning her father’s financial struggle. Hugh, in common with many others, would know that her parents had divorced amidst a scandal that had impoverished Walter Dewey. It had been a terrible time for them all and she didn’t intend to now pick at the painful memory.

‘I expect you missed your mother’s guidance during your come-out.’

Hugh abhorred hypocrisy so avoided judging others’ morality. He was no paragon and had had illicit liaisons with other men’s wives, although neither of his current mistresses was married. He therefore found it hard to understand why Arabella Dewey had left her husband and children. In polite society the customary way of things was to seek discreet diversion when bored with one’s spouse. But it seemed Arabella hadn’t been able to abide Walter’s company. Hugh found that rather sad, as he sensed the fellow was basically a good sort and the couple had produced two beautiful girls.