Полная версия

Mapping Le Tour: The unofficial history of all 100 Tour de France races

“In big cities, in small towns, in villages and on the plains, you see – waiting impatiently at the side of the road – old ladies and little girls, school teachers and priests…”

The universal appeal of the Tour de France, as described by French writer Pierre Bost in the newspaper Marianne, July 1935

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Foreword by Mark Cavendish

Introduction by Ellis Bacon

How to use this book

Tour statistics

1903–1914, Editions 1–12

1919–1939, Editions 13–33

1947–1959, Editions 34–46

1960–1979, Editions 47–66

1980–1999, Editions 67–86

2000–2013, Editions 87–100

2014, Edition 101

The Tour’s most memorable places

Index

Acknowledgments

Copyright

About the Publisher

Foreword by Mark Cavendish MBE

The Tour de France is a special race for all professional cyclists. It is the biggest, the best, the toughest and the most competitive on the circuit. This year’s race, starting in Yorkshire, is even more special.

I can say from experience that just completing the Tour is an impressive achievement for even the best cyclists in the world. It was not until my third Tour that I had a chance to race down the Champs-Élysées and finish a Tour de France. Since it started, the race was intended to be sport’s ultimate physical challenge, a sentiment that comes across clearly in this book. Since that first completion, I’ve finished the race a further four times, and every year has offered a uniquely challenging experience.

One of the reasons we get drawn back to racing around France every year is that a different route, with new tests and problems to overcome, is picked for each edition. The route is just as much of a challenge in the Tour as the other riders, but it also gives us a chance to travel to new places each year, experiencing different areas of France with our team-mates.

The highlight of every race for me is definitely that sprint finish along the Champs-Élysées. When that also ends with winning the final stage in front of the Paris crowds it becomes the dream of any competitive cyclist. I feel privileged to have done it four times and I’m looking forward to doing it a few more!

After a hundred races across the fields and mountains of France and its neighbouring countries, it’s amazing to think of the history of the Tour, the legends it has made, and the tragedies that have happened. From the gentlemen disqualified in 1904 for taking the train to the latest issues that the sport has experienced, the route, rather than any individual rider, is always the star of the event. Perhaps this is why the Tour has survived and flourished despite all of its controversies.

This book is a detailed textual and visual biography of the Tour itself, and one which uniquely places the document we refer to the most, the map, at its core.

Each stage of the Tour has characteristics that cyclists all over the world can recognise and be inspired by. This can most easily be imagined through maps. I study the route map in detail, both before the first stage and throughout the Tour. It’s the key to planning my race strategy, and the team’s. Sometimes you have to pick your battles and know which stages to target to try to win, and in which ones you’re just going to have to fight it out for survival in the peloton while the climbers slog it out at the front. We get all this by studying the route map along with the stage profiles.

When I was young I followed the Tour de France, watching it avidly on television. It inspired me on my bike rides around the Isle of Man and led to dreams about competing in the race. It is great to see a book that captures the history of this incredible event and lets us look back at the Tour with fond memories, whether following or taking part in the race as it travels around France.

Introduction by Ellis Bacon

The Tour de France is all about mapping and geography – it is its very lifeblood. It seems fitting, then, that the Tour came about as a result of some geographical wranglings, of sorts: the so-called Dreyfus Affair.

In 1894, Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French Army, was accused of spying for Germany, although it later came to light that he had been framed by an anti-Semitic army colleague.

France was divided by the case, and the editor of sports newspaper Le Vélo, Pierre Giffard, was very much on Dreyfus’s side. That grated with the paper’s advertisers, such as bike and tyre manufacturers Adolphe Clément, Edouard Michelin and Count Jules-Albert de Dion, who were very much anti-Dreyfusards, and so began looking for somewhere else to advertise their wares. Feelings were such that Giffard certainly didn’t want them in his paper anymore, either.

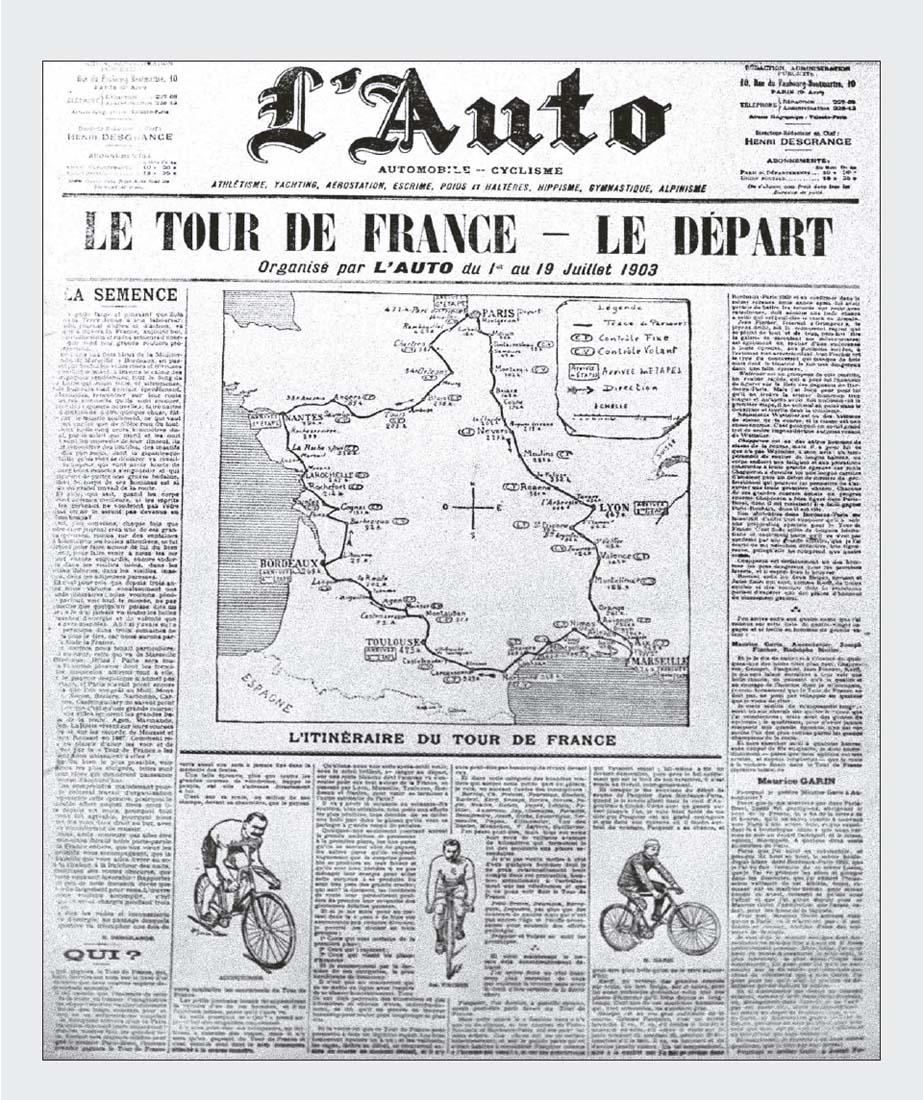

Clément turned to his director of publicity, Henri Desgrange – a former racing cyclist who had already published a book about bike training called La Tête et les Jambes (‘The Head and the Legs’) – and on 16 October 1900, new newspaper L’Auto was first published, with Desgrange at the helm.

Despite the proliferation of anti-Dreyfusard advertisers, the new title struggled when it came to sales, and in November 1902 – over lunch, bien sûr – one of L’Auto’s writers, Géo Lefèvre, came to his ailing paper’s rescue by proposing a ‘Tour de France’ bicycle race. The rest is history.

Except it’s not that simple, as the 1904 edition of the race – as you can read in these pages – was almost its last, thanks to cheating.

Then in 1998 the race was rocked to its core once more thanks to the Festina doping affair. So serious was it, in fact, that then-race director Jean-Marie Leblanc feared that the ‘98 edition genuinely would be the race’s last. It has been shaken yet further by more recent events, too, but still it survives – simply ‘there’, year after year, it seems, as much a part of France as baguettes or the Eiffel Tower.

Compiling this book has been a true labour of love and, fittingly, a journey, as I delved as deeply into my own experiences and memories as I did into my collection of cycling books and magazines, and even my university dissertation.

It all came back to me: the reason why I, and millions like me, are so enamoured with the Tour de France and its history, and in particular the places it’s visited, the riders it’s created and the lives it’s touched. Hopefully ‘Mapping le Tour’ will convey all of that.

Did my love of all things French come before or after my awareness of the Tour? I don’t remember any more, but what I do know is that they have always been inextricably linked: it may be a cliché, but the Tour is truly a French institution.

This, though, is a book that focuses more on the geographical side of the race than simply the epic tales that make up the Tour’s history, although of course they, too, are inextricably linked.

In 2014, the race celebrates its 101st edition, having started in 1903 but having been interrupted by the two world wars. The first Tour I saw was the finish of the 1986 edition when it was shown on UK television by Channel 4. By the following year, I was hooked, and my next French project at school was about the Tour, and in particular about British rider Tom Simpson and his collapse on Mont Ventoux in 1967. I devoured the race’s history, its geography and its language – the latter then very much French; now increasingly, and a little disappointingly, English.

I studied French at university; my third year abroad was a toss-up between spending it in Avignon (close to Mont Ventoux) or in Chambéry – near to the legendary climb of Alpe d’Huez. Provence won out in the end – helped, a little, by Marcel Pagnol and Peter Mayle’s tales, sans doute – and I soon found out that the university hall of residence in which I was to live had been the old hospital in which Simpson had died.

My dissertation that year, written in French, could only be about the Tour, and I subtitled it La Grande Boucle – ‘The Big Loop’ – as it’s affectionately known in France.

That same year – 1998, which, thanks to the aforementioned Festina doping affair, was also memorable for all the wrong reasons – I managed to watch the race live for the first time on French soil, at Carpentras for the finish of stage 13, and again the next day for the start of the fourteenth stage in nearby Valréas. (I’d already skipped school in 1994 to watch the race come through Brighton when it came to the UK – with my parents’ blessing, of course.)

In 2001, when I was living in Denmark, I met up with my dad to watch the start of the Tour in Dunkirk. That night, after the prologue – won by Christophe Moreau – we slept in the car at some motorway services to save money, and then continued on to the start of stage 1 in St-Omer. Incidentally, my dad now always buys those small bottles of St-Omer lager, proving that the commercial side of the Tour definitely ‘works’.

After hours slumped on a metal crowd barrier at the finish of the stage in Boulogne-sur-Mer, waiting for the race to arrive, our trip was rounded off nicely by watching Erik Zabel show Romans Vainsteins a clean pair of heels to take the bunch sprint.

I’d enjoyed following the Tour as a fan and, just two years later in 2003, I would follow it for the first time as a journalist.

Since then, I’ve returned year after year, which strangely means that I haven’t really noticed the race’s rather swift evolution from French holiday to English-speaking-dominated sports event. That dominance looks set to continue, but the race remains fiercely French in its goal of showcasing the country’s stunning countryside and terrain.

Each October, the unveiling of the following year’s route in Paris is eagerly awaited by the world’s press, and by the Tour’s millions of fans at home. Once that familiar hexagonal shape of France with the race route laid out across it is beamed around the world, people begin to plan their holidays around it. The riders, meanwhile, get straight to work, scouting out the roads – and the climbs in particular – named on the following year’s itinerary. It is that hard work and attention to detail, across the winter and in the early part of the season, that marks out the true contenders from the also-rans come the summer.

The Tour has also gone beyond the confines of France, and over the years has enjoyed sojourns to Belgium, Italy, Spain and Switzerland, as well as seeking out new roads further afield, in the Netherlands, Ireland and Britain. The Pyrenees made their first appearance in 1910, while the Alps followed in 1911. It also makes regular visits to the Massif Central, and the Vosges mountains in eastern France, where the riders have tackled the Puy de Dôme and the Ballon d’Alsace, respectively.

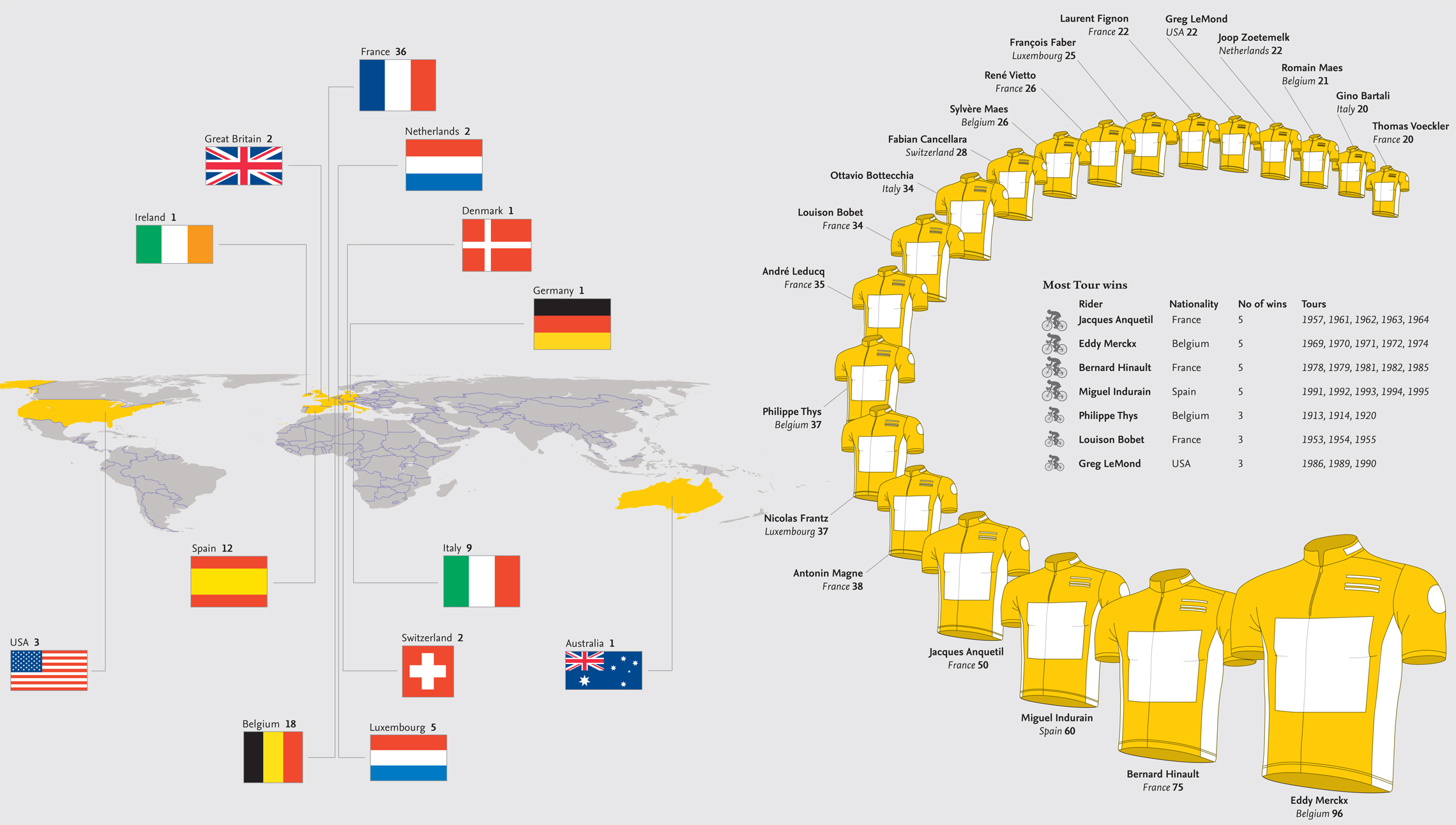

Host cities such as Paris, Lyon, Marseille and Bordeaux have appeared regularly on the route since the Tour’s first edition in 1903, and as cities in countries other than France were added, so, too, grew the breadth of contenders. As well as ever-increasing numbers of riders from neighbouring countries like Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Italy and Spain, ‘international milestones’ include the first participation by an African rider, Tunisian Ali Neffati, at the 1913 Tour, and the first riders from Australia – Snowy Munro and Don Kirkham – a year later in 1914. In 1937 came the first British riders – Bill Burl and Charles Holland – although neither finished; it wasn’t until 1955 that Brian Robinson and Tony Hoar became the first Brits to complete the Tour. Greg LeMond became the first American stage winner in 1985 and, after the Colombia-Varta team’s appearance at the Tour in 1983, Victor Hugo Peña becoming the first Colombian to wear the yellow jersey, albeit for only three days, in 2003.

Today, the Tour organisation is faced with the task of ensuring that the enduring image of riders toiling up fan-filled mountain sides and streaming past sunflower-filled fields does indeed endure … To paraphrase Tour boss Christian Prudhomme’s message, which he is at pains to get across: the Tour exists to allow people to dream.

The scenery and routes used allow people in far-flung corners of the world to see France in a justly flattering light: laid bare in all its glory for the riders to fight against and the spectators – both roadside and televisual – to appreciate. It is an event that has made national and international heroes of previously local heroes, and has brought life to corners of France, and the globe, that needed it…

Long may it continue.

How to use this book

Map symbols

The Route

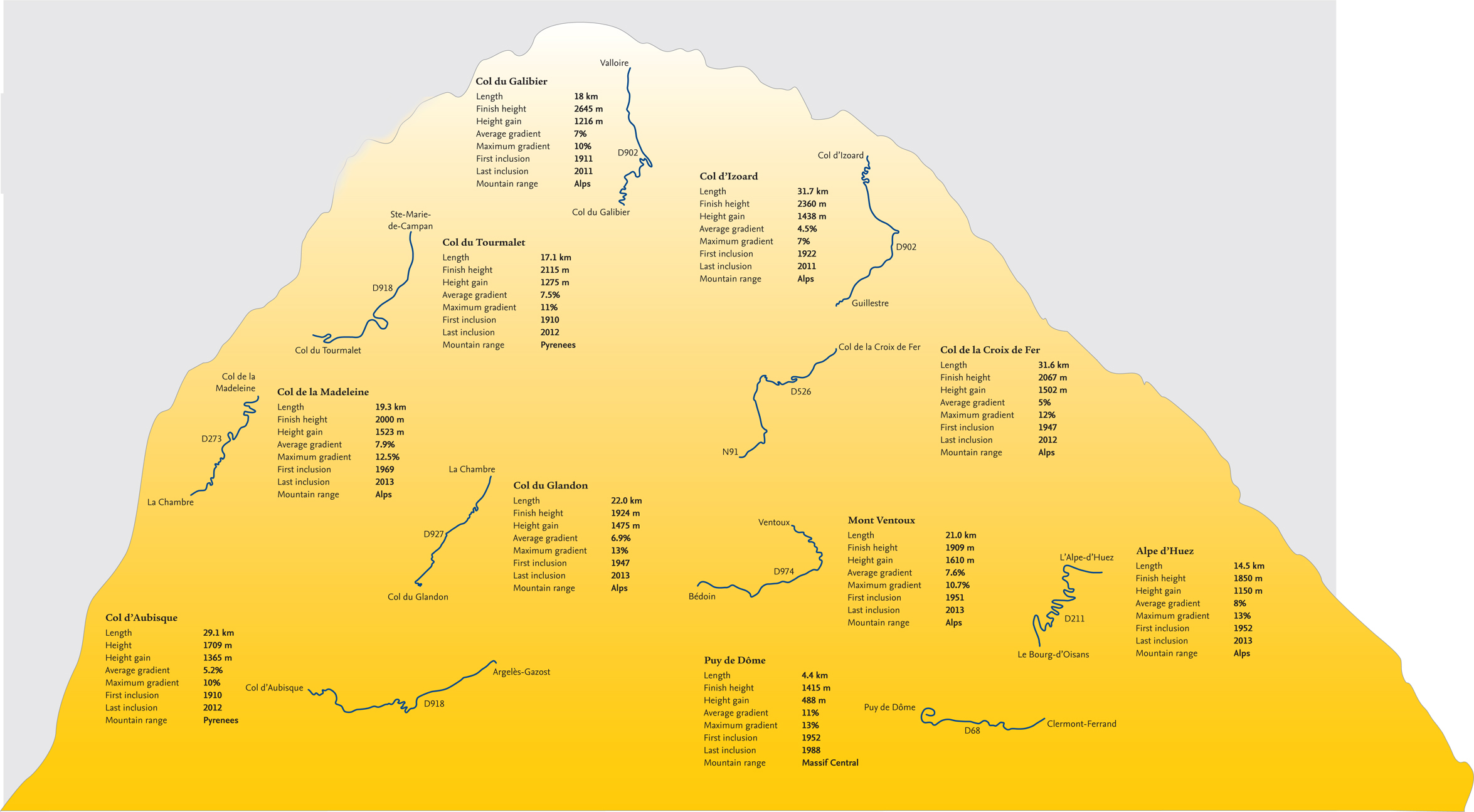

The Climbs

“I had one of the hardest moments ever on the Col du Glandon in 1977. I was at the end of my career, and what I had was gone by then.”

Eddy Merckx

Top 10 highest climbs

Climb Range Highest point Cime de la Bonette Alps 2802 m Col de l’Iseran Alps 2770 m Col Agnel Alps 2744 m Col du Galibier Alps 2645 m Col du Grand St-Bernard Alps 2473 m Col du Granon Alps 2413 m Col d’Izoard Alps 2360 m Col de la Lombarde Alps 2351 m Col de la Cayolle Alps 2326 m Val-Thorens Alps 2275 m

Many battles have been won and lost over the Tour’s mountain stages. Whether it is in the Alps, Pyrenees or the Massif Central, riders need grit, determintaion and extraordinary fitness to overcome the punishing ascents of these now famous climbs.

The Winners

Tour wins by country

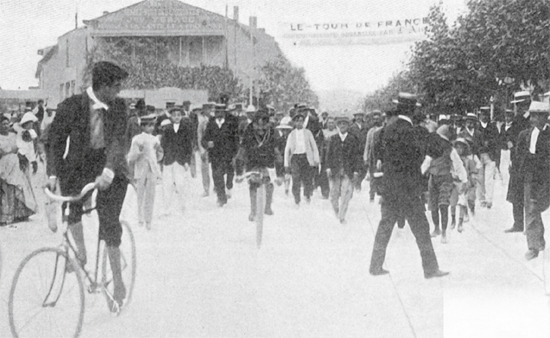

Riders make their way from Lyon to Marseille during stage 2 of the first Tour de France. Only twenty-one competitors would complete the race, covering 2428 km (1509 miles) in six days.