Полная версия

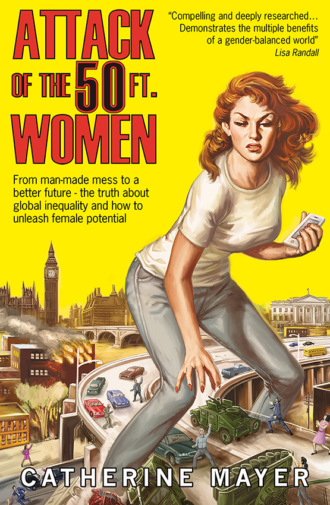

Attack of the 50 Ft. Women: From man-made mess to a better future – the truth about global inequality and how to unleash female potential

She set a template for the female leader who sweeps in to sort out the mess created by men. Cometh the hour, cometh the woman. The press dubbed Merkel Germany’s Margaret Thatcher. Inevitably Sturgeon became Scotland’s Margaret Thatcher and Theresa May transmogrified into Margaret Thatcher in kitten heels or, when that comparison wore thin, Britain’s Merkel. ‘Women are such rare creatures that they can only be understood through the prism of one another, like unicorns or sporting triumphs by the England football team,’ observed the journalist Hadley Freeman.12

This barb held true after May entered Downing Street as Britain’s second female Prime Minister, called a June 2017 snap election aiming to increase her mandate to negotiate Brexit and instead lost the Conservatives their parliamentary majority. This left her government dependent on the backing of the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), a party led by another woman of tarnished reputation, Arlene Foster. Northern Ireland’s delicate power-sharing agreement had foundered over Foster’s role in a scandal involving an over-generous incentive scheme to boost renewable energy that handed taxpayers a hefty bill. May and Foster display many weaknesses as politicians. Their critics attack them as female politicians. The journalist and broadcaster Janet Street-Porter typified this approach, writing a piece entitled ‘Theresa May’s incompetence has set women in politics back decades.’

Women aren’t immune to making sweeping assumptions about women, about female difference – whether that difference is female failure or, just as often, female superiority . ‘If Lehman Brothers had been Lehman Sisters, today’s economic crisis clearly would look quite different,’ IMF chief Christine Lagarde told an interviewer in 2008.

The idea of women as the antidote to male leadership is a familiar discourse in public life. Whenever economies falter or politics stutters, the refrain starts again. Men plunder the environment; women manage it. Men start wars; women make peace. We need more women in high and influential positions. We need more women to tower. Bring on the new breed of 50-foot women!

With so many people apparently inclined to this argument, not just rebels and advocates of social justice, but great swathes of the political classes, pillars of the establishment, corporate bigwigs and analysts focusing so hard on the bottom line that they walk into lampposts, surely we must be able to make substantial progress towards gender equality? With the dangers of failure laid bare in countries that are shredding hard-won rights, surely we have no choice but to redouble our efforts? Where are the traps and barricades obstructing the road to Equalia? Does anyone even know the way? And will it take 50-foot women to get us there?

In 2015, I kicked off a process that would provide fascinating and unexpected answers to those questions.

I accidentally started a political party.

Westminster’s first-past-the-post voting system reliably delivered single-party victories until a Conservative–Liberal Democrat government emerged from the 2010 elections. Five years later, as fresh elections hove into view, the coalition partners sought to win voters’ favour by vilifying not only the Labour opposition but each other.

For that reason alone, the political debate I attended at London’s Southbank Centre on 2 March 2015 felt excitingly unorthodox. As part of the Women of the World (WOW) Festival, the Conservatives’ Margot James, the Lib Dems’ Jo Swinson and Labour’s Stella Creasy described overlapping experiences and ambitions. They debated companionably, listening intently, nodding appreciatively and applauding each other’s points.

This should have been thrilling. Instead it was dispiriting. In 66 days we faced a choice not between these vibrant women but their parties.

The Lehman Brothers’ collapse in 2008 had ushered in an age of deficit-cutting measures that often hit the poorest hardest, and that meant a disproportionate impact on women. In the UK, as in most other countries, the male-dominated mainstream that steered towards the crisis also took the wheel to direct the recovery.

There were significant dividing lines, of course. Tories, Lib Dems and Labour disagreed over the degree, speed and targets of proposed cuts, but not one of them made serious efforts to apply a gender lens to the discussion. They needed only to look over to tiny Iceland to see the difference that could make. Prime Minister Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir did attract international attention – she wasn’t just Iceland’s first female Prime Minister, she was the world’s first openly lesbian premier. Less noted, and at least as noteworthy, her coalition took a consciously gender-aware approach to the economic crisis. The country’s three largest banks had failed, its currency collapsed, the stock market plummeted and interest on loans soared. As businesses bankrupted, jobs vanished. Cuts in state spending were inevitable, but in planning them, Jóhanna’s coalition tried to diminish the pain by spreading it thinner.13 Where other nations cut state sector jobs and prioritised capital investment, effectively supporting male employment at the expense of sectors employing and serving women, Iceland took a different tack. It asked a simple question: why build a hospital, but cut nursing staff?

‘The typical reaction of a state to a crisis is to cut services because they’re seen as expenses,’ says Halla Gunnarsdóttir, who served as a special adviser in the Icelandic coalition. ‘The state puts money into construction because it’s seen as investment. So basically it cuts jobs for women, and also takes away services and replaces them with women’s unpaid labour: care for the elderly, care for the disabled, caring for children and those who are ill. Then it creates jobs for men so that they can continue working.’14 This is often done through public–private partnerships in which the state takes the risk but the private sector benefits. Women’s unemployment goes up as the state focuses on preserving jobs for men.

Such perspectives – and women themselves – were conspicuous by their absence in the 2015 election and the broader landscape looked bleak. Of 650 electoral constituencies, 356 had never elected female MPs. Labour did better on getting women into Parliament, but the Tories remained the only major party to have chosen a female leader, and that had been 40 years earlier.

Labour women did try to elbow their way into the front line of the campaign. Harriet Harman, the party’s deputy leader, long saddled with the nickname ‘Harperson’ by sections of the press hostile to her feminist politics, commissioned research that revealed that 9.1 million women had chosen not to exercise their votes at the previous election. ‘Politics is every bit as important and relevant to the lives of women as it is to men. Labour has set itself the challenge to make this case to the missing millions of women voters,’ she said.

In truth, Labour had done no such thing. Harman couldn’t get her male colleagues to treat gender as a core issue, and ended up scrambling together a separate campaign. Her party had a proud heritage on women’s equality: it appointed the first ever female cabinet minister (Margaret Bondfield in 1929), pioneered equal pay legislation, made strides on early years provision for children, and in introducing all-women shortlists in 1997 engineered the biggest single increase in female representation in the Commons. Of the intake of 418 Labour MPs elected in Tony Blair’s first landslide victory, 101 were women. The total number of female MPs in the previous parliament across all parties had been just 60.

Yet these achievements sit alongside more problematic strains, a culture descended from a struggle for the rights of the working man that often viewed female workers not as part of that struggle but as competition, and an ideological underpinning that in seeing gender inequality as fixable only by fixing all power imbalances too often sends women to the back of the queue to wait their turn. In every vote for the Labour leadership involving women, female candidates have come last. In 2016 MP Angela Eagle withdrew her bid to replace Jeremy Corbyn after a male MP put himself forward, in a brain-twisting piece of logic, as an alternative unity candidate. ‘If Labour had an all-women leadership race, a man would still win,’ tweeted the journalist Stephen Daisley.

Harman had climbed higher in Labour than any other woman, elected the party’s Deputy Leader when Gordon Brown succeeded Tony Blair in Downing Street. Her predecessor as Deputy Leader, John Prescott, had also served as Deputy Prime Minister. She never got that status and further slights followed. ‘Imagine the consternation in my office when we discovered that my involvement in the London G20 summit was inclusion at the No. 10 dinner for the G20 leaders’ wives,’ Harman said later.15 Heading into the 2015 election, now deputy to Ed Miliband, Harman found herself sidelined by male advisers, consultants and politicians. Her riposte trundled into view in February of that year, apparently blushing with shame that such a stunt should be necessary.

‘That pink bus! Oh my god, the pink bus!’ Sitting in a café in the Southbank Centre, I listened to a table of women holding their own debate ahead of WOW’s. They, like me, found the political choices on offer to voters about as exciting as a limp egg-and-cress sandwich. They, too, cringed to see Harman’s pink bus touring constituencies with its cargo of female MPs. For all its noble intent – and its effectiveness; the negative publicity generated what spin doctors call ‘cut through’, drawing voters who might otherwise not have engaged – it was tough to get past that pinkness.

The women at the Southbank Centre were weighing exactly the response Harman’s pink bus was supposed to head off. They were considering not voting at all. ‘There’s nobody to vote for,’ said one of them.

A tube train rumbled beneath us, or perhaps it was Emmeline Pankhurst spinning through the soil of Brompton Cemetery. Then again, Pankhurst overestimated the transformative power of suffrage. ‘It is perfectly evident to any logical mind that when you have got the vote, by the proper use of the vote in sufficient numbers, by combination, you can get out of any legislature whatever you want, or, if you cannot get it, you can send them about their business and choose other people who will be more attentive to your demands,’ she declared in 1913. Yet here we were, 86 years after full enfranchisement, still waiting to be fully enfranchised.

This proved to be the inescapable subtext of the whole evening. For all that James and Swinson and Creasy had won admission to the House of Commons, they had not thrived as their talent suggested they should. Swinson was a junior minister, Creasy held the equivalent position on the opposition benches. James served as a Parliamentary Private Secretary, two rungs below a junior minister.

If Westminster didn’t value them enough to put them at its top tables, the media helped to reinforce that view. I understood the reasons for this. After 30 years as a journalist, latterly a decade at TIME magazine, I was well aware that media companies – like political parties – were still far from closing the gender gap. Male cultures inevitably produce distorted and inadequate coverage of women. For female journalists, sexual harassment by colleagues or interviewees is an occupational hazard as routine and inescapable as a stiff neck from too much time at the computer. Pay and promotional structures value male staff over their female colleagues and, in admitting too few women to decision-making, maintain a male sensibility about which stories should be covered and how. This can be insidious – women receive less coverage than men and what they do often appears labelled ‘lifestyle’ – or it may express itself in hostility and mockery. Swinson gave an example of the latter during the WOW discussion: her observation during a parliamentary debate that boys might want to play with dolls mutated in the Sun’s reporting into a proposal to mandate boys to play with Barbies.16 New media also meant new challenges. Creasy had become the target of virulent Twitter trolls spewing rape and death threats, simply by virtue of being female.

The trio set out the problems of women in politics compellingly. They had some answers. Yet it was equally evident that they had little power to make change and little prospect of more power. So when Jude Kelly, the artistic director of the Southbank Centre and moderator of the event, invited the audience to volunteer proposals to speed gender equality, I found myself clutching the microphone.

I explained that when Jude conceived of WOW in 2009, she had recruited me to the founding committee. I talked about the sense of female community and commonality the festival always generates, and congratulated the MPs on demonstrating their spirit despite party political differences.

I continued: ‘I, like many other people, come to this election knowing that whatever the outcome, it will be disappointing. It would be so much more exciting – we would be spoiled for choice – if the three of you were the leaders of the parties.’

The audience whooped in agreement.

‘The questions you’ve all been asking this evening are about not only how we make progress but how we hold onto progress. So what I would like to do is invite anybody who wants to come to the bar afterwards or interact with me on Twitter to consider whether one way of doing this might be to actually found a women’s equality party, one that works with women in the mainstream parties that are doing the good things, and indeed with men in those mainstream parties who are doing the things that need to be done, but works rather in the way of some fringe parties that we’ve seen coming up to push [gender equality] so that it finally really is front and centre of the agendas of mainstream parties. At which point we’d happily dissolve our party, go away and leave the mainstream parties to what they should be doing.’

‘So that is my question. I will be at the bar afterwards.’

‘Are you buying, Catherine?’ asked Creasy.

I could have reduced that whole rambling, unplanned intervention to two observations: old politics was failing and its failure was creating room for change; mainstream parties had lost their core identities and were therefore primed to copy anything that looked like it might be a vote winner. If you build it, they will come.

The growth of the Green Party had provided mulch for green shoots in other parties. When the United Kingdom Independence Party started winning serious support, the other parties gave up challenging its anti-immigration rhetoric and started contorting themselves into UKIP-shaped positions. It wouldn’t be until the results of the EU Referendum the following year that we would begin to see the full consequences of the copycat syndrome, but it was already clear that UKIP didn’t need to be in government to transform Britain. The threat to women posed by a surging UKIP and the success of similar parties in other countries was also becoming evident. They represented a backlash against a whole range of values, including gender equality. ‘The European Parliament, in their foolishness, have voted for increased maternity pay,’ UKIP leader Nigel Farage had tweeted in 2010. ‘I’m off for a drink.’ Why couldn’t a women’s equality party steal from their political playbook to assert the opposite view? Why couldn’t a women’s equality party trigger copycat impulses in the established parties and finally push the interests of the oppressed majority to the top of the political agenda?

People enthused about the idea the moment the words came out of my mouth. They also assumed, to my alarm, that I was proposing to do something to make it a reality. Some followed me to the bar and yet more joined the discussion in the perpetual pub of social media. I returned home to an empty house and an empty fridge and before going to sleep left a message on Facebook to amuse friends who knew of my musician husband’s dedication to eating well. ‘Andy’s only been on tour for 24 hours and I’ve already had a sandwich for dinner. And started a women’s equality party.’ I added: ‘Want to join? Non-partisan and open to men and women.’

‘I’m in!’ replied the writer Stella Duffy almost instantaneously. ‘Me too,’ declared Sophie Walker, a Reuters journalist who could not anticipate just how deeply in she would soon find herself. By the next morning, the thread had lengthened considerably and all the responses were similar.

I called Sandi Toksvig, broadcaster, writer, comedian, and, in the pungent prose of a Daily Mail columnist, ‘a vertically challenged and openly lesbian mother’. She too was on the WOW founding committee and two weeks earlier we had talked at a committee dinner about how to channel the energy the festival always generated into transformative politics. We hadn’t discussed specific mechanisms, so I thought she might be interested to hear about my spontaneous proposal at the Women and Politics event. Her response wasn’t quite as anticipated.

‘But that’s my idea,’ she said. Each year she concocted a show called Mirth Control as a finale for WOW and for 2015 was planning to bring onto the stage cabinet ministers from an imaginary women’s equality party. She’d been on the point of ringing me with a proposition. ‘Darling,’ she said. ‘Do you want to be foreign secretary?’

The idea of someone with no Cabinet experience and a habit of making off-colour jokes becoming the UK’s premier advocate abroad made me laugh, but that was before Theresa May appointed Boris Johnson to the role. However both Sandi and I aspired to see more female secretaries of state.

Days after WOW’s glorious finale, we sat down together and lightly took decisions over a few beers that would disrupt our lives and many others. We decided to give it a go, try to start a party. We swiftly concluded we weren’t the right people to lead it. Sandi is the funniest woman in the world but her wit is a shield that conceals an enduring shyness. She would never have willingly put into the public domain details about her private life – she came out in an interview with the Sunday Times in 1994 – had she not faced twin pressures. Tabloids threatened to reveal her ‘secret’, and she felt compelled to campaign for lesbian and gay rights and equal marriage. Her revelation earned death threats that sent her into hiding with her young children. The last thing she wanted was more disruption. ‘Can we go home yet?’ she asks me, often and plaintively. It’s a joke but there’s always truth to Sandi’s humour.

We also feared we were too metropolitan, too media, to rally the inclusive movement we envisaged. For the party to be effective, it had to be as big and diverse a force as possible. That meant getting away from the assumption that the left had sole ownership of the fight for gender equality. It meant a commitment to a collaborative politics dedicated to identifying and expanding common ground, and that in turn demanded a serious effort to build in diversity from the start. That diversity had to include a wide range of political affiliations and leanings.

Sandi also realised she’d have to give up her job as host of the BBC’s satirical current affairs show, The News Quiz. It was a move her fans didn’t easily forgive. After the announcement, the ranks of my regular trolls swelled with angry Radio Four listeners venting their displeasure.

Even before Sandi’s public involvement, our meetings, advertised only on Facebook and by word of mouth, drew hundreds. From the first such gathering, on 28 March 2015, came confirmation of the party’s name. Some participants argued for ‘Equality Party’, but that risked diffusing the message while potentially reinventing the Labour Party. Others favoured Gender Equality Party as an easier sell to male and gender non-binary voters, but that had the ring of a student society in a comedic campus novel. Sandi has little patience for the discussion, which has continued to flare. ‘We just thought we’d be clear,’ she says. ‘We’re busy women and we didn’t really want our agenda to be a secret.’ ‘Women’s Equality Party’ is direct, unambiguous and produces the acronym WE, pleasingly inclusive if apt to spark toilet humour. Politics, as we would learn at first hand, involves compromise.

Speakers at that first meeting included Sophie Walker, later elected WE’s first leader by the steering committee that also emerged from that meeting. At the second meeting on 18 April we signed off on six core objectives: equal representation, equal pay, an education system that creates opportunities for all children, shared responsibilities in parenting and caregiving, equal treatment by and in the media, and an end to violence against women and girls. In June, our first fundraiser at Conway Hall in London sold out within hours. In July 2015, WE registered as an official party. October saw the launch of our first substantial policy document, compiled in close consultation with experts, campaigning organisations and grassroots support that already amounted to tens of thousands of members and activists. WE raised over half a million pounds by the year end. In May 2016 we secured more than 350,000 votes at our first elections for London Mayor, the London Assembly, the Welsh Assembly and the Scottish Parliament.

A month later, I encountered Boris Johnson’s father, Stanley, a former Member of the European Parliament, at the birthday gathering of another politician. ‘Catherine,’ he shouted across the room. ‘I heard some terrible news about you!’ The room fell silent, heads swivelled. ‘I heard you’d become a feminist!’ Later that evening I talked to a Labour peer who berated me for splitting his party. This was a feat Labour was managing without external help. At the same event, prominent members of Labour and the Conservatives confessed they’d voted for us. Westminster was no longer patronising and dismissing us, but it wasn’t yet sure what to make of us either.

WE’s second year was more eventful still. Our first party conference in Manchester in November 2016, attended by 1,600 delegates, adopted a raft of new policies including a seventh core objective, equal health, and ratified an internal party democracy devised to give branch activists a guaranteed presence on decision-making bodies and ensure real diversity on those bodies. We ran campaigns that had significant impact such as #WECount – mapping sexual harassment, assault and verbal abuse directed against women. Tabitha Morton ran for WE in the first race to be Metro Mayor of the Liverpool’s city region, spurred to do so because the region had no strategy for combating violence against women and girls, despite having the UK’s highest reported rates of domestic violence. After the election she was asked by the winner, Labour’s Steve Rotheram, to help him to implement the strategy she made central to her campaign.

We began detailed work with other parties too. The Liberal Democrats asked for help in drafting legislation to combat revenge porn – the disclosure of intimate images without consent. Several parties and politicians opened conversations with us about much closer cooperation, including the possibility of alliances and joint candidacies.

We didn’t expect to road-test these ideas before the general election scheduled for 2020. Our plan was to build up our war chest ahead of that deadline and gain experience and exposure by participating in the May 2017 local council elections and the contest for the newly created post of the mayor of the Liverpool region. Then, while those races were still under way, May called her snap election.

We fielded five candidates in England and one apiece in Scotland and Wales, on a radical and innovative platform that understood social care not as an unfortunate expense but the potential motor of the economy, and proposed fully costed universal childcare. Large chunks of our original policy document resurfaced in the manifestos of other parties. In the Yorkshire constituency of Shipley, Sophie Walker stood with the backing of the Green Party, in a progressive alliance. The joint WE–Green target was the Conservative incumbent, Philip Davies, a prominent antifeminist. We hoped Labour might join us – they had largely abandoned hope of the seat after serial defeats – but instead they chose to run and directed more of their energy against us than Davies. This reflected both Labour’s belief that it owns feminism and an overheated partisan culture that rejected all opportunities for electoral pacts across the UK.