Полная версия

Chocolate Wars: From Cadbury to Kraft: 200 years of Sweet Success and Bitter Rivalry

Chocolate Wars

From Cadbury to Kraft – 200 Years of

Sweet Success and Bitter Rivalry

DEBORAH CADBURY

To Pete and Jo, Martin and Julia, with love

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Introduction

Part One

Chapter 1 - A Nation of Shopkeepers

Chapter 2 - Food of the Gods

Chapter 3 - The Root of All Evil

Chapter 4 - They Did Not Show Us Any Mercy

Chapter 5 - Absolutely Pure and Therefore Best

Part Two

Chapter 6 - Chocolate that Melts in the Mouth

Chapter 7 - Machinery Creates Wealth but Destroys Men

Chapter 8 - Money Seems to Disappear Like Magic

Chapter 9 - Chocolate Empires

Chapter 10 - I’ll Stake Everything on Chocolate

Part Three

Chapter 11 - Great Wealth is Not to be Desired

Chapter 12 - A Serpentine and Malevolent Cocoa Magnate

Chapter 13 - The Chocolate Man’s Utopia

Chapter 14 - That Monstrous Trade in Flesh and Blood

Chapter 15 - God Could Have Created Us Sinless

Part Four

Chapter 16 - I Pray for Snickers

Chapter 17 - The Quaker Voice Could Still be Heard

Chapter 18 - They’d Sell for 20p

Chapter 19 - Gone. And it was so Easy

Epilogue

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

List of text illustrations

List of plates

About the Author

By The Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

When I was a young child, the knowledge that a branch of my family had built a chocolate factory filled me with wonder. What sort of charmed life did such a possibility offer to my relatives? Each Christmas I had an insight when the most enormous case arrived from my uncle, Michael Cadbury, containing a large supply of mouth-watering chocolates. Even more memorable was the trip I made in the early 1960s to see how the chocolate was made. As I opened the door to the factory at Bournville in Birmingham, the sight that greeted me was magical.

To my child’s eyes it was as though I had entered a cavernous interior that belonged to some benign, orderly and highly productive wizard who had somehow saturated the very air with a chocolate aroma. My uncle and parents raised their voices against the whirr of machinery. But I did not hear them. All I could see was chocolate. It was all around me, in every stage of the manufacturing process. There was molten chocolate bubbling in vats towering above me, vats so huge that they had ladders running up their sides. Chocolate rivers flowed on a number of swiftly-moving conveyers through gaps in the wall to mysterious chambers beyond. Solid chocolate shaped in a myriad of exciting confections travelled in neat, soldierly processions towards the wrapping department. Such a miracle of clockwork precision and sensual extravagance was hard to take in. Even more puzzling to my young mind was the question of how this chocolate feast, which brought the idea of greed to a whole new level, fitted with religion? For even though I did not yet understand the connection, I did know that the chocolate works were, in some inexplicable way, intimately connected with a religious movement known as Quakerism. Was all this the hand of God?

My own father had left the Quakers just before the Second World War. He wanted, as he put it, to ‘join the fight against Hitler’, a stance that was not compatible with Quaker pacifism. I was brought up in the Church of England, and as a child, when I joined my cousins for Quaker meetings, I felt as if I were on the outside looking in on a strange, even mystical tradition. Long silences endured in bare rooms, stripped of anything that might excite the senses, where grownups contemplated the surrounding void, were incomprehensible to me. Equally incomprehensible: how did my rich, chocolate relatives acquire that admirable restraint, that air of wholesome frugality? Even family picnics had a way of turning into long and chilly route marches, raindrops trickling down my back. The wealth and the austerity seemed oddly incongruous. Did the one contribute to the other? Cheerful homilies from my father along the lines of ‘Many a mickle makes a muckle’ and ‘Look after the pennies and the pounds will look after themselves’ did not supply a satisfactory answer. Even a five-year-old knew this was not the key to creating a chocolate factory.

A generation passed before I decided to retrace my steps up Bournville Lane. This time it was personal. I wanted to delve into the Bournville and family archives to uncover the whole story. When I turned the corner in the lane in the autumn of 2007, my heart skipped a beat as I was taken back to that day when my father and uncle, both now much missed, had taken me round the factory. To my surprise, the chocolate works seemed even larger than I remembered. Imposing red-brick blocks stood beside the neatly mowed cricket pitch, with Bournville village and green nestled behind. At this time, Cadbury was the largest confectioner in the world, and the only independent British chocolate enterprise to survive from the nineteenth century. I wanted to understand the journey that took my deeply religious Quaker forebears from peddling tins of cocoa from a pony and trap around Birmingham to this mighty company that reached around the globe.

The story began five generations ago, when the far-sighted Richard Tapper Cadbury, a draper in Birmingham in the early nineteenth century, sent his youngest son, John, to London to study a new tropical commodity that was attracting interest among the colonial brokers of Mincing Lane: cocoa. Was it something to eat or drink? Richard Tapper saw it pre-eminently as a nutritious non-alcoholic drink in a world that relied on gin to wash away its troubles. Never could my abstemiously inclined ancestor have guessed what fortunes would be entwined with the humble cocoa bean, although it seemed full of promise, a touch of the exotic.

His grandsons, George and Richard Cadbury, turned a struggling business into a chocolate empire in one generation. In the process, they found themselves in competition with their Quaker friends and rivals Joseph Rowntree in York, and Francis Fry and his nephew Joseph in Bristol. The Cadbury, Fry and Rowntree dynasties were built on values that form a striking contrast with business ethics today. Their approach to the creation of wealth was governed by a code of practice developed over hundreds of years since the English Civil War by their Quaker elders and set out at yearly meetings and in Quaker books of discipline. This nineteenth-century ‘Quaker capitalism’ was far removed from the excesses of the world’s recent financial crisis, with business leaders apparently seeing no harm in pocketing huge personal profits while their companies collapsed.

For the Quaker capitalists of the nineteenth century, the idea that wealth-creation was for personal gain only would have been offensive. Wealth-creation was for the benefit of the workers, the local community and society at large, as well as for the entrepreneurs themselves. Reckless or irresponsible debt was also seen as shameful. Quaker directives ensured that no man should ‘launch into trading and worldly business beyond what they can manage honourably . . . so that they can keep their words with all men’. Even advertising was dismissed as dishonest, mere ‘puffery’: the quality of the product mattered far more than the message. Men like Joseph Rowntree and George Cadbury built chocolate empires at the same time as writing ground-breaking papers on poverty or studies of the Bible, or campaigning against a multitude of Dickensian human rights abuses. Puritanical hard work and sober austerity, with the senses kept in watchful restraint, were the guiding principles.

While it is easy to dismiss such values as antiquated, Quaker capitalism proved extraordinarily successful, and generated a staggering amount of worldly wealth. In the early nineteenth century, around 4,000 Quaker families in Britain ran seventy-four banks and over two hundred companies. As they came to grips with making money, these austere men of God also helped to shape the course of the Industrial Revolution, and the commercial world today.

The chocolate factories of George and Richard Cadbury and Joseph Rowntree inspired men in America such as Milton Hershey, the ‘King of Caramel’, who took philanthropy to a new, all-American scale with the creation of the utopian town of Hershey in the cornfields of Pennsylvania. But the chocolate wars that followed the growth of global trade, and the emergence in the twentieth century of international rivals – such as Frank and Forrest Mars – unshackled by religious conviction, gradually eroded the values that had shaped Quaker capitalism. Some Quaker firms did not survive the struggle, and those that did had little choice but to abandon their Puritan roots. In the process, ownership of the businesses passed from private Quaker dynasties to public shareholders. Little by little, the results of the transition from Quaker capitalism to shareholder capitalism began to take shape in the form of the huge confectionery conglomerates that straddle the corporate world.

Today the world’s two largest food giants – the Swiss Nestlé and America’s Kraft – operate around the globe, feeding humanity’s sweet tooth. Nestlé, with five hundred factories worldwide, sells a billion products every day, giving annual sales of £72 billion. Kraft operates 168 factories, and has annual sales of £26 billion. While these two behemoths are locked in a race to maintain market share in the developed world, they are also selling their Western confections and other processed foods to emerging markets in the developing world. Somewhere along the way the four-hundred-year-old English Puritanical ideal of self-denial and the Quaker vision of creating wholesome nourishment for a hungry and impoverished workforce have disappeared. Also vanished are a myriad of independent chocolate confectionery firms. In Britain alone, Mackintosh of Halifax and Rowntree of York are now owned by Nestlé, while Terry of York, Fry of Bristol and Cadbury have become a division of Kraft.

The origins of this book lie in my search to explore how this happened. I wanted to unearth the true story of the original Quaker chocolate pioneers and the religious beliefs that shaped their business decisions, and to see how their values differ from those of today’s company leaders. At first sight it can appear that globalisation has been profitable for all. It is hard to dispute economists’ claims that the process has lifted billions of people across the world out of the poverty that was on the doorstep of the cocoa magnates of the nineteenth century. But that has also come at a significant cost.

My last visit to Bournville, on a bitterly cold January day in 2010, formed a stark contrast to the peaceful charm of my earlier visits. Outside the factory, staff members with banners were protesting against Kraft’s recently announced takeover of Cadbury. ‘Kraft go to hell,’ said one. In a symbolic gesture, another protester set fire to a huge Kraft Toblerone bar. Unite, Britain’s biggest trade union, had warned that thousands of jobs could be eliminated under Kraft. ‘Our members feel very angry and very betrayed,’ said Jennie Formby, Unite’s national officer for food and drink industries. Kraft was borrowing £7 billion to fund the takeover, and many feared that Cadbury could become ‘nothing more than a workhorse used to pay off this debt’, its assets stripped and jobs lost. For the Quaker pioneers, the workforce and the local community were key stakeholders in the business, and they aimed to enhance their lives. Now, with their future uncertain, there was a mood of alienation and powerlessness amongst the staff outside Bournville that day.

Quite apart from the effects on employees and communities, there are additional concerns raised by the Kraft takeover of Cadbury that bring the contrast between Quaker business values and shareholder capitalism sharply into focus. For the nineteenth-century Quaker, ownership of a business came with a deep sense of responsibility and accountability to all stakeholders involved. In today’s system of shareholder capitalism the shareholder is divorced from the responsibilities of business ownership.

The spirit of a business – so crucial to the motivation of its staff – is hard to define or measure. It is not to be found in the buildings or the balance sheet, but it is reflected in the myriad of different decisions taken by those at the helm of the business. The Quaker pioneers believed that ‘your own soul lived or perished according to its use of the gift of life’. For them, spiritual wealth rather than the accumulation of possessions was the ‘enlarging force’ that informed business decisions. But gone now, lost in another century, is that omnipotent all-seeing eye in the boardroom, reminding those Quaker patriarchs of the fleeting nature of their power. And what is there to replace it?

The story of the Quaker chocolate pioneers and their rivals is, in a way, a parable of our times, highlighting a bigger transformation in our society. By examining the ‘chocolate wars’ that have shaped the world of confectionery, I hope to shed light on a process of change that affects us all.

Part One

Chapter 1

A Nation of Shopkeepers

In the mid-nineteenth century, Birmingham was growing fast, devouring the surrounding villages, woods and fields. The unstoppable engine of the Industrial Revolution had turned this once modest market town into a great sprawling metropolis in the heart of the Midlands. Country-dwellers hungry for work drove the population from 11,000 in 1720 to more than 200,000 by 1850. In the city they found towering chimneys that turned the skies thunder grey, and taskmasters unbending in their demands. Machines never stopped issuing the unspoken command: more toil to feed the looms, to fire the furnaces and to drive the relentless wheels of commerce and industry far beyond English shores.

Birmingham was renowned across the country for innovation and invention. According to the reporter Walter White, writing about a visit to the city in Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal in October 1852, ‘To walk from factory to factory, workshop to workshop and view the extraordinary mechanical contrivances and ingenious adaptations of means to ends produces an impress upon the mind of no common character.’ The town was a beacon of industrial might and muscle. This was where fire forged iron and coke, metal and clay to make miracles.

Birmingham’s foggy streets resounded with hammers and anvils fashioning bronze and iron into buttons, guns, coins, jewellery, buckles and a host of other Victorian artefacts. Walter White marvelled at the ‘huge smoky toyshop’ and the ‘eager spirit of application manifested by the busy population’. But he was evidently less taken with the sprawling town itself, which he considered ‘very ill arranged and ugly’, and dismissed as ‘a spectacle of dismal streets’.

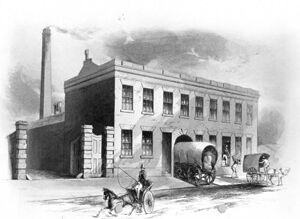

At the heart of these dismal streets, opposite today’s smartly paved Centenary Square, was a road called Bridge Street, which in 1861 was the site of a Victorian novelty: a cocoa works. Approached down a dirt road, past busy stables, coach houses and factories, it was surprisingly well hidden. But wafting through the grimy back-streets was a powerful aroma, redolent of rich living. Guided by this heady perfume the visitor was drawn past the blackened exterior, through a narrow archway into a courtyard with an entrance leading off to the heart of the chocolate factory. It was to this modest retreat that two young Cadbury brothers hurried one day early in 1861.

There was a crisis in the family. Twenty-five-year-old Richard and twenty-one-year-old George Cadbury knew that the wonderful aroma of chocolate disguised a harsher reality. The chocolate factory and its owner, their father, John Cadbury, were in decline. The family faced a turning point. The business could go under completely. John Cadbury turned to his sons for help.

Photographs of the time show George and Richard Cadbury soberly dressed in plain dark Victorian suits with crisp white shirts and bow ties. Richard’s soft features contrast with his younger brother, whose intensity of focus and air of concentration is not relaxed even for the photographer. ‘I fixed my eye on those who had won,’ George admitted later. ‘It was no use studying failure.’ He had, said his friends, ‘boundless ambition’. And he needed it. The family firm was haemorrhaging money.

By chance, Walter White toured the Bridge Street factory, and has left a vivid account of what it was like in 1852. Leaving behind the storehouse crammed with sacks of raw cocoa beans from the Caribbean, he entered a room that blazed with heat and noise: the roasting chamber. With its four vast rotating ovens, ‘the prime mover in this comfortable process of roasting was a 20 horse steam engine’.

After this, ‘with a few turns of the whizzing apparatus’, the husk was removed by the ‘ceaseless blast from a furious fan’ and the cocoa, ‘now with a very tempting appearance’, was taken for more ‘intimate treatment’. This occurred in a room where ‘shafts, wheels and straps kept a number of strange looking machines in busy movement’. Following yet more pressing and pounding, finally a rich, frothing chocolate mixture flowed, ‘leisurely like a stream of half frozen treacle’. This was formed into a rich cocoa cake which was shaved to a coarse powder ready for mixing with liquid for drinking. Upstairs, White found himself in a room where management ‘had put on its pleasantest expression’. The female employees, all dressed in clean white Holland pinafores, were ‘packing as busily as hands could work. No girl is employed,’ he added, ‘who is not of a known good moral character.’ Such a factory, he concluded, was ‘a school of morality and industry’.

Cadbury’s cocoa works at Bridge Street, Birmingham, in the mid-nineteenth century.

But almost ten years had passed since Walter White’s visit, and the ‘school of morality and industry’ had been quietly dying of neglect. George Cadbury was quick to appraise the desperate situation. ‘Only eleven girls were now employed. The consumption of raw cocoa was so small that what we now have on the premises would have lasted about 300 years,’ he wrote. ‘The business was rapidly vanishing.’

During the spring of 1861, George and Richard wrestled with their options. Pacing the length of the roasting room in the evenings, the four giant rotating ovens motionless, the dying embers of the coke fire beneath them faintly glowing, the brothers could see no simple solution. George had harboured hopes of developing a career as a doctor. Should he now join his brother in the battle to save the family chocolate business? Or close the factory? Would they be able to succeed, where their own father had failed?

It was their father, John, who had proudly shown Walter White around the factory in 1852. In the intervening years he had been almost completely broken by the death of his wife, Candia. John had watched her struggle against consumption for several years, her small frame helpless against the onslaught of micro-organisms unknown to Victorian science. Equipped only with prayers and willpower, he took her to the coast hoping the fresh air would revive her, and brought in the best doctors.

But nothing could save her. By 1854, Candia had gratefully succumbed to her bath chair. Eventually she was unable to leave home, and then her room. ‘The last few months she was indeed sweet and precious,’ wrote John helplessly. When the end came in March 1855, ‘Death was robbed of all terror for her,’ he told his children. ‘It was swallowed up in victory and her last moments were sweet repose.’ Yet as the weeks following her death turned into months John failed to recover from his overwhelming loss. He was afflicted by a painful and disabling form of arthritis, and took long trips away from home in search of a cure. After years of diminishing interest in his cocoa business, Cadbury’s products deteriorated, its workforce declined and its reputation suffered.

Richard and George knew their father’s cocoa works was the smallest of some thirty manufacturers that were trying to develop a market in England for the exotic New World commodity. No one had yet uncovered the key to making a fortune from the little bean imported from the New World. There was no concept of mass-produced chocolate confectionery. In the mid-nineteenth century, the cocoa bean was almost invariably consumed as a drink. Since there was no easy way of separating the fatty cocoa oils, which made up to 50 per cent of the bean, from the rest, it was visibly oily, the fats rising to the surface. Indeed, it often seemed that the novelty of purchasing this strange product was more thrilling than drinking it.

John Cadbury, like his rivals, followed the established convention of mixing cocoa with starchy ingredients to absorb the cocoa butter. As his business had declined, the proportion of these cheaper materials had increased. ‘At the time we made a cocoa drink of which we were not very proud,’ recalled George Cadbury. ‘Only one fifth of it was cocoa – the rest was potato flour or sago and treacle: a comforting gruel.’

This ‘gruel’ was sold to the public under names such as Cocoa Paste, Soluble Chocolate Powder, Best Chocolate Powder, Fine Crown, Best Plain, Plain, Rock Cocoa, Penny Chocolate and Penny Soluble Chocolate. Customers did not buy it in the form of a powder but as a fatty paste, made up into a block or cake. To make a drink at home, they chipped or flaked bits off the block into a cup and added hot water, or if they could afford it, milk. It is a measure of how badly the Cadbury cocoa business was faring that three-quarters of the Bridge Street factory’s trade came from tea and coffee sales.

Although promoted as a health drink, cocoa had a mixed reputation. Unscrupulous traders sometimes coloured it with brick dust and added other questionable products not entirely without problems for the digestive system: a pigment called umber, iron filings or even poisons like vermilion and red lead. Such dishonest dealers also found that the expensive cocoa butter could be stretched a little further with the addition of olive or almond oil, or even animal fats such as veal. The unwary customer could find himself purchasing a drink which could not only turn rancid, but was actually harmful.

While the prospects for the family business in 1861 did not look hopeful, the alternatives for Richard and George were limited. Quakers, like all non-conformists, were legally banned from Oxford and Cambridge, the only teaching universities in England at the time. As pacifists, they could not join the armed services. Nor were they permitted to stand as Members of Parliament, and they faced restrictions in other professions such as the law. As a result, many Quakers turned to the world of business, but here too the Society of Friends laid down strict guidelines.

In a Quaker community, a struggling business was a liability. Failing to honour a business agreement or falling into debt was seen as a form of theft, and was punished severely. If the cocoa works went under owing money Richard and George would face the censure of the Quaker movement; at the worst, they could be disowned completely and treated as outcasts. Quite apart from these strict Quaker rules, in Victorian society business failure and bankruptcy could lead to the debtors’ prison or the dreaded workhouse, either of which could lead to an early grave.